It is widely known that the seven-day week and two-day weekend came into being through religious traditions—namely, the biblical creation story, biblical Sabbath law, and Jesus’s resurrection on a Sunday. The use of the acronyms “BC” and “AD” likewise owes its origin to an early medieval calculation of the year Jesus was born. But while these modern conventions are so ubiquitous as to be easily taken for granted, details of the cyclic, annual religious calendars of all three Abrahamic faiths (the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic Calendars) also influence the lives of many people around the world today.

| Number | Christian (Gregorian) | Jewish | Muslim (Islamic / Hijri) |

| 1 | January | Nisan | Muharram |

| 2 | February | Iyar | Safar |

| 3 | March | Sivan | Rabi al-Awwal |

| 4 | April | Tammuz | Rabi al-Thani |

| 5 | May | Av | Jumada al-Ula |

| 6 | June | Elul | Jumada al-Thani |

| 7 | July | Tishri | Rajab |

| 8 | August | Cheshvan (Marcheshvan) | Sha‘ban |

| 9 | September | Kislev | Ramadan |

| 10 | October | Tevet | Shawwal |

| 11 | November | Shevat | Dhu al-Qidah |

| 12 | December | Adar* | Dhu al-Hijjah |

*In Jewish leap years, there are two Adars: Adar I and Adar II

Solar Versus Lunar Calendars

Realizing the religious origin of the seven-day week, a ten-day week was established briefly during the French Revolution as part of a secularizing effort. The twelve-month year, however, is not religiously derived, so it was retained.

The regular movements of the heavenly bodies provide a universally available metric for measuring time. Humans have used the 24-hour, light-and-dark cycle to mark the beginnings and endings of individual days since they began taking an interest in such things. The summer and winter solstices, also created by the Earth’s relationship to the sun, likewise provide convenient points for measuring the larger periods we call years.

However, it is the cycle of the moon rather than the sun that can most readily help human beings measure periods of time longer than days and shorter than years. This explains why, in many languages including English, the word for “month” derives etymologically from the word for “moon.” Indeed, in some languages, the same word is used for both the time period and the celestial body. By contrast, the seven-day week does not appear to be tied to anything in the natural world.

Despite their mutual usefulness, integrating the solar and lunar cycles into a comprehensive, globally applicable system for tracking the passage of time is complicated. Eventually, the solar cycle pushed the lunar cycle aside to the degree that the moon is virtually ignored in the modern, “secular” calendar.

Some religious traditions, however, have not been willing to give up on the moon. All three of the great Abrahamic faiths have instituted holidays that are observed by virtually all their adherents on the same days of the year (though Christianity has been less successful than Islam and Judaism—see below). But setting the days required compromise with the sun. A single lunar cycle is slightly more than 29 and a half days long. Twelve such months lead to a 354-day year. Unwilling to allow their holidays to drift continually from season to season, Jews and Christians found different ways to reconcile their respect for the moon’s cycle with the sun’s dominance over the Earth’s climate. Muslims, meanwhile, give the moon uncompromising priority.

| Aspect | Solar Calendar | Lunar Calendar |

| What it’s based on | Earth’s relationship to the sun (seasons, solstices). | The moon’s cycle (about 29.5 days). |

| Year length | Aligns with the solar year and seasons. | 12 lunar months ≈ 354 days, shorter. |

| Role today | Dominates the modern secular calendar. | Largely pushed aside in secular use. |

| Religious use | Jews and Christians adjust to keep holidays in seasons. | Muslims give the moon priority for holidays. |

Islam’s Lunar Calendar

The Muslim calendar is the most purely committed to the lunar cycle of the three Abrahamic faiths. In Islamic reckoning, a year is determined by the moon’s cycle, and years are simply understood to be 354 days long. However, because the lunar cycle is not exactly 29 and a half days long, Muslim scholars found it necessary to add a day to the last lunar month every two or three years. This is not to bring the calendar into sync with the solar cycle but to merely ensure that the Earth’s rotation is taken into account. In other words, it reconciles the daily nighttime and daytime sequence—determined by Earth’s rotation relative to the sun—with the moon’s visibility relative to both.

As a result of Islam’s preference for the moon’s cycle over the sun’s, the Muslim year and its holidays are continually moving earlier and earlier across the solar year. This can seem confusing to those who are accustomed to associating the movement of a year with the passing of meteorological seasons. But if one simply remembers that the moon is prioritized over these seasons in Islam, the system is actually quite lucid compared to those of the other Abrahamic faiths.

Islamic religion’s strict connection to the moon over the sun suggests something about its essential nature. Islam claims to be a religion for everyone. Thus, its holidays could not practically be connected to the seasons of the year, which are opposite each other in the northern and southern Hemispheres. There is no harvest festival in Islam, for example. Its preference for the moon, thus, is both simplifying and instructive.

Key Holidays in Islam

The two central holidays of Islam are Eid al-Fitr, the “festival of fast-breaking,” and Eid al-Adha, the “sacrifice festival.” Respectively, these commemorate Muhammad’s reception of the first revelation of the Qur’an and Abraham’s sacrifice of a ram as a substitute for his oldest son.

Eid al-Fitr arrives on the first day of the tenth month of the Islamic calendar, called Shawwal. But its significance is attached to what is remembered during the previous month, called Ramadan. Muslims believe that Muhammad received his first revelation of the Qur’an during the last ten days of Ramadan on a night called the Laylat al-Qadr—the “night of power.” Muslims all over the world mark the end of this month by breaking their annual month-long fast, which all able-bodied Muslims are expected to observe.

Eid al-Adha is a memorial of Abraham’s sacrifice of a ram in place of his son Ishmael. Muslims understand Abraham’s willingness to obey God as a supreme act of faith. The Qur’an depicts Ishmael as willingly encouraging his father to obey God’s command to follow through with the sacrifice, and thus in Islam, he joins Abraham as an exemplar of submission to God’s will. Abraham’s knife is stayed by the angel Jibril’s (Gabriel) intervention.

This event is memorialized every year on the tenth of Dhu al-Hijja, the twelfth and last month of the Islamic calendar. Muslim families that can afford to do so purchase an animal, kill it according to Islamic regulations, and butcher the meat. Two-thirds of the meat is typically then distributed among family and friends, and another third is given to Muslims who do not have the means to make their own sacrifices.

Other Islamic holidays are widely recognized in the religion, but none have the status of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha.

| Holiday | When (Islamic Calendar) | What It Commemorates |

| Eid al-Fitr | 1st day of Shawwal (10th month) | Marks the end of Ramadan and commemorates Muhammad’s first revelation of the Qur’an. |

| Eid al-Adha | 10th of Dhu al-Hijja (12th and final month) | Commemorates Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice his son and God’s provision of a ram instead. |

Judaism’s Lunisolar Calendar

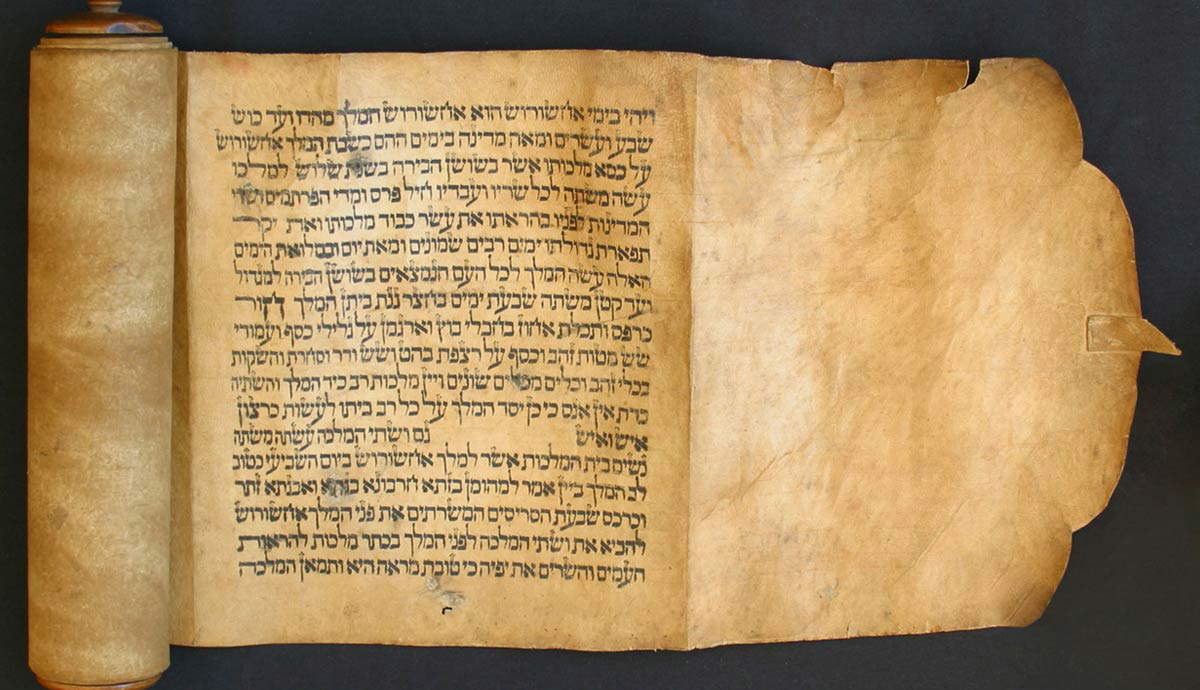

The Hebrew Bible contains the basic instructions for the Jewish calendar, and on first reading, it appears that it was to be based on the lunar cycle. However, the Jewish calendar cannot be based purely on the lunar cycle because its foundation is the holiday of Passover, which the Bible specifies is to be celebrated in the springtime.

Unlike Islam and Christianity, Judaism was never intended to be everyone’s religion. Jews see themselves as the ethnic descendants of biblical Israel, which was divinely selected out of all the world’s nations to represent the world to God. Thus, Judaism’s holiday traditions stem from Israel’s story, which occurred in and around the land of ancient Israel. Many Jews today live in the southern hemisphere, but due to Israel’s historic locale, Passover must fall within the springtime of the northern hemisphere. There is therefore a need within Judaism to pay attention to the sun’s cycle as well as to the moon’s.

At the same time, the Bible also provides precise dates, based on lunar months, for when holidays are to be observed. Therefore, Jews have been obliged to develop a relatively complex formula in order to ensure that (1) Jews worldwide celebrate their holidays on the same days of the year, (2) the holidays fall on the days of the lunar month specified in the Bible and, (3) the holidays remain in the correct meteorological seasons of the year. As one can imagine, this was no easy feat and required considerable debate and calculation.

Compromising With the Sun

Keeping Passover in the springtime meant adjusting the entire, lunar-based calendar outlined in the Bible. The Bible does not explain how this is to be accomplished, so it was left to Jewish scholars to come up with a formula. Along with the names of the months themselves, Jews of the Babylonian diaspora adopted the system that had been developed in that region of reconciling the lunar months with solar years. In this system, an “extra” month is added to seven different years within a 19-year cycle (known as the “Metonic cycle,” after the Greek astronomer Meton of Athens), which prevents the holidays from traveling outside the meteorological seasons in which they belong. This extra month comes between the months of Shevat and Adar. When this happens, the month added becomes Adar I (or a variation), and Adar itself is called Adar II (or a variation). If a year contains these two months of Adar it is called a shanah ibbur, meaning an “enlarged” or “pregnant” year. In English, it is often simply referred to as a “leap year.”

Judaism’s compromise with the sun allows Jews to remain cognizant of the moon’s cycle while also staying in harmony with the seasonal nature of their holidays. Consequently, the new moon does not always coincide with the first of the month.

Key Holidays in Judaism

The “High Holidays” of Judaism begin and close a ten-day period of repentance and confession within the month of Tishri (September/October). They begin with Rosh Hashanah on the first of Tishri, and end with Yom Kippur—the “Day of Atonement”—widely considered the holiest day of the Jewish year. While known now as the “Jewish New Year,” Rosh Hashanah is called the “festival of trumpets” in the Bible and is still marked by the ritual of the blowing of the shofar—the horn of a sheep transformed into a musical instrument.

Passover (pronounced Pesach in Hebrew) falls in the middle of Nisan, the seventh month of the year (except during a shanah ibbur—see above). This means it is directly halfway through the year from Rosh Hashanah. Passover is perhaps the most well-known Jewish festival. It is a remembrance of the Israelite escape from enslavement in Egypt. The Passover meal is shared after sundown on the fourteenth of Nisan, and the next day is recognized as a Sabbath, no matter what day of the week it happens to be.

Shavuot (lit. “weeks”) for Jews today is a memorial of God’s giving of the Torah to Moses. The Bible itself does not make this connection, however. In the Bible, Shavuot appears to be a harvest festival. It occurs exactly seven weeks after Passover. This holiday was later called “Pentecost,” after the Greek word for “fiftieth,” as it falls 50 days after the Passover meal is shared.

Another holiday whose roots are remembered as being from the Exodus experience is Sukkot, a word meaning “tents” or “tabernacles.” This week-long festival is a favorite of children. Jewish families spend the week in tent-like or temporary shelters to remember the Israelites’ period of wandering in the Sinai wilderness before their entry into the land God had promised to give Abraham’s descendants hundreds of years before.

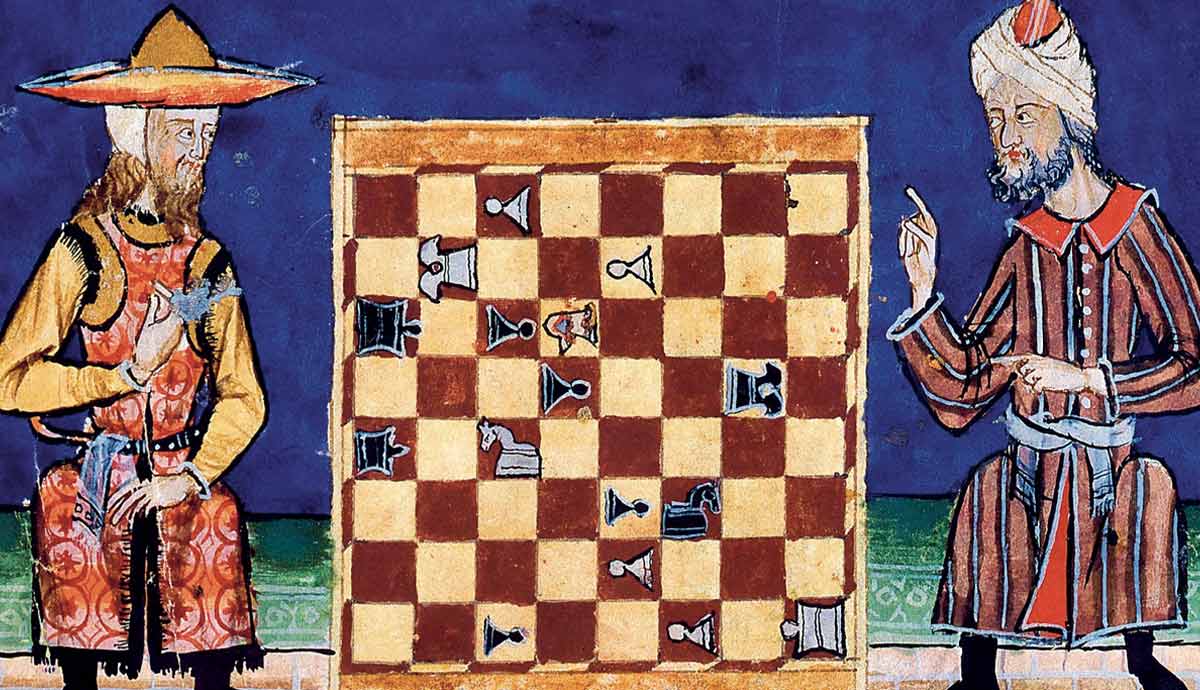

These holidays are remembered in Judaism as being the first established in their tradition. Many others commemorate important events in Jewish history. Most notably Purim and Hanukkah, which celebrate Jewish survival and resilience, are also important for Jewish religious practice today.

| Holiday | When (Jewish Calendar) | What It Commemorates |

| Rosh Hashanah | 1st of Tishri | Start of the “High Holidays”; “festival of trumpets,” shofar blowing, Jewish New Year. |

| Yom Kippur | 10 days after Rosh Hashanah (end of High Holidays) | Day of Atonement, repentance and confession; holiest day of the year. |

| Passover (Pesach) | Middle of Nisan, meal on 14th of Nisan | Remembrance of the Israelites’ escape from enslavement in Egypt. |

| Shavuot | Seven weeks (50 days) after Passover | Memorial of God’s giving of the Torah to Moses; originally a harvest festival. |

| Sukkot | After the Exodus-related holidays (week-long) | Living in temporary shelters to recall Israelite wandering in the wilderness. |

| Purim | 14th of Adar (14th of Adar II in leap years) | Celebrates Jewish survival and resilience. |

| Hanukkah | Starts 25th of Kislev and lasts 8 days | Also celebrates Jewish survival and resilience. |

The Bible and Jewish Holidays

Judaism is exceptionally rich in holidays and religious seasons, and its traditions have developed through various contexts and experiences over more than two millennia. It is important to keep this development in mind since later additions and evolutions of meaning can be inadvertently conflated with their biblical roots. For example, the holiday that later became known as Rosh Hashanah (lit. “head/beginning of the year”) in exilic Judaism appears in the Bible as the “Festival of Trumpets” on the first day of Tishri—the seventh month of the year. According to the Bible’s telling, God commanded the Israelites just before their exodus from Egypt that the month of their deliverance from enslavement would be the first of their new calendar. This later came to correspond to the month of Nisan.

It is sometimes difficult to square the biblical explanations with the meanings that holidays came to bear later on in a thoroughgoing way. Understanding the Jewish calendar, thus, requires observing its living activity within the religion, since the ongoing traditions do not always correspond directly to biblical material.

Easter in Christianity’s Hybrid Calendar

Christianity’s calendar memorializes events that happened in the life of Jesus. Because Jesus was a Jew who claimed to bring the Israelite history to its fulfillment, and because he was crucified on Passover, Christianity’s most important holidays are closely related to some Jewish holidays. However, Christianity chose a different path from Judaism for reconciling the lunar and solar cycles. As a result, Passover only occasionally lines up with the day Christians memorialize Jesus’s death, which is the Friday before Easter Sunday. In addition, Christians always align their celebration of Pentecost with Easter Sunday rather than Passover, with the result that, like Easter, Pentecost always falls on a Sunday, though for Jews it could fall on any day of the week.

The reasons behind these differences are twofold. First, Christianity chose to prioritize Sunday in its calculation of Easter’s timing, since it was the day of Jesus’s resurrection. Second, because Christianity’s holidays were ultimately intended to memorialize events in the life of Jesus—who gave no instruction about creating holidays in his own honor—they did not have any biblical strictures to satisfy. Loyalty to the moon, thus, was not nearly as important to them.

Christmas in Christianity’s Hybrid Calendar

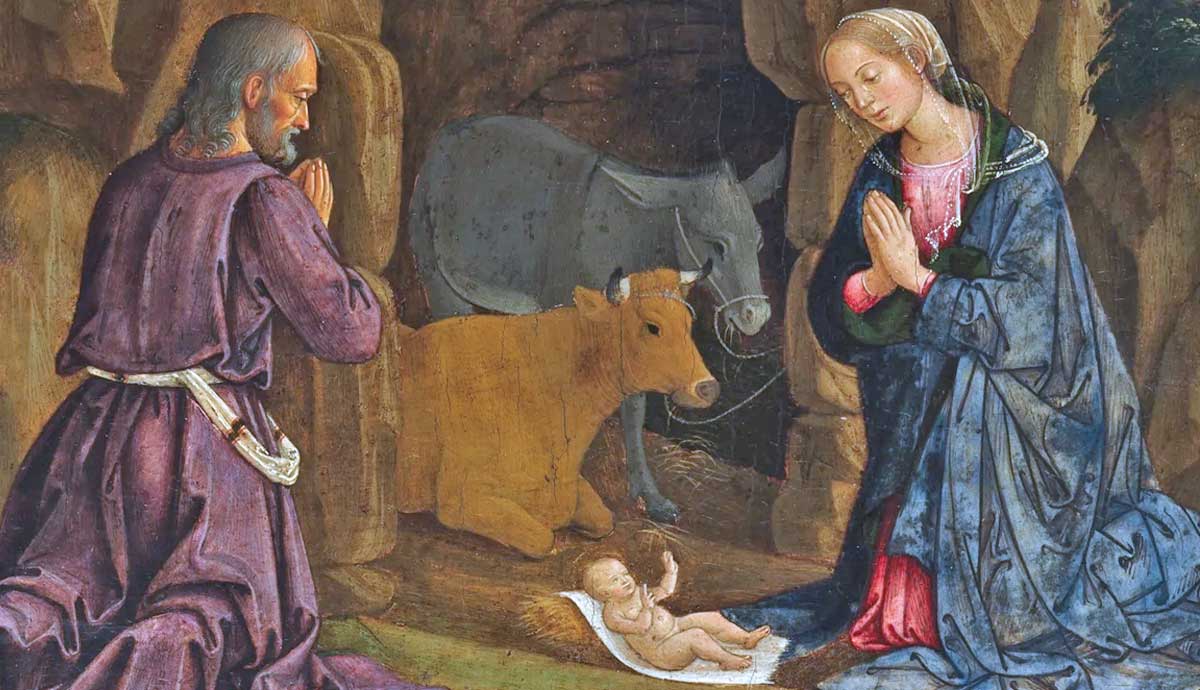

After Easter, Christmas is the most important Christian holiday. Unlike Easter, Christmas occurs on a set day—December 25th—every year. The decision about the dates of both of these holidays was agreed upon at the ecumenical Council of Nicaea, which met in 325 CE in what is now Iznik, Turkey. Nicholas of Myra, known today as Saint Nicholas and associated with the mythical Santa Claus and Father Christmas, was present at this council.

It was decided that the date of Easter would be calculated with the moon in mind, but that it must always be on a Sunday. Formally, it is the first Sunday after the first full moon that appears after the first day of spring—a day determined by the solar cycle. The moon, thus, plays a role but only in deference to the sun.

With time, Christians began to recognize the four weeks leading up to Christmas as the “Advent” season, in which emphasis is placed on joy and anticipation of God’s coming to live with humanity. The 40-day period (but skipping Sundays) leading up to Easter is called “Lent.” Lent emphasizes repentance in anticipation of the tragedy of Jesus’s execution, and also thankfulness for his self-giving. Other, less widely celebrated holidays also tend to relate closely either to the beginning or end of Jesus’s life.

The Western Versus the Eastern Christian Calendar

When the Council of Nicaea met, the Julian Calendar (named after Julius Caesar) was in use throughout the Roman/Byzantine Empire. While this calendar demonstrated awareness of the need for leap years, its calculation was slightly off because it is necessary to skip leap years at certain intervals in order for the meteorological seasons to continue to stay in tune with the months that are customarily associated with them. It was not until Pope Gregory XIII in the late 16th century that the calendar was changed to account for this problem.

But by that time the Eastern and Western Churches had split, and most of the Eastern Church was not willing to adopt the new calendar. To this day the split persists and is epitomized by the two churches’ celebration of Easter on different days almost every year and of Christmas every year. With time, Christmas will eventually be a summer holiday in the Eastern Orthodox traditions of Christianity. Easter, however, continues to be connected to the cycles of the moon and sun rather than a fixed calendar only. Thanks to their dependability, all Christians everywhere occasionally celebrate the resurrection of Jesus on the same day.

Recap

| Aspect | Christian Calendar (Gregorian) | Jewish Calendar | Muslim Calendar (Islamic / Hijri) |

| Main type | Solar | Lunisolar (solar and lunar combined) | Purely lunar |

| Basis | Earth’s orbit around the sun and the seasons | Moon cycles for months, adjusted to the sun | Moon cycles only |

| Typical year length | About 365.24 days | Normally 12 months, ~354 days, with leap years adding a 13th month | 12 lunar months, about 354–355 days |

| Months and years | Fixed months, fixed seasons | Months follow the moon; extra month added some years to keep holidays in season | Months follow the moon, no adjustment to seasons |

| Relation to holidays | Most feasts on fixed solar dates; some (like Easter) use both sun and moon | Major holidays (Rosh Hashanah, Passover, etc.) stay in roughly the same seasons | Major holidays (Ramadan, Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha) move through the seasons over time |