In the early 3rd century CE, the senator and historian Cassius Dio complained that the rise of Rome’s emperors changed the nature of power. According to him, during the Republic, under the Senate, business was conducted in public. Now, the emperor ruled Rome as if it was his private household. While Cassius Dio is clearly a partisan reporter, he is correct in his observation that the imperial system opened new pathways to power, especially for imperial women. A focus on dynastic succession gave women an important role to play in the question of legitimacy, and as mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters, they had enviable access to the ear of the emperor. This is the story of Rome’s empresses, the women behind the Caesars.

Female Power Before the Empire

While women were excluded from Roman politics, one woman played an important role in the foundation of the Roman Republic. According to legend, in 508 BCE, Lucretia, the wife of a man named Collatinus, was defiled by Tarquinius Superbus, the King of Rome. Unable to bear the shame, Lucretia committed suicide. Her death so outraged the Romans that, under the leadership of the first Brutus, they rose up and threw out the kings for good. From out of the power vacuum left by the departed kings emerged the Republic.

Rome was a profoundly patriarchal society, and Lucretia had no political agency by which she could seek justice against Tarquinius. She did have influence over the men in her life, though it took an extreme act to move them. The “behind the scenes” influence of women is a recurring theme in Roman history.

Women were usually relegated to the private sphere. Aristocratic households were headed by men, known as the paterfamilias, who had authority over their wives. But just as the tutelary spirit (genius) of the paterfamilias was worshipped in the household shrine, so was the tutelary deity (juno) of his wife, suggesting that her role in the home was prominent, but in most cases ended at the door. When a woman’s influence extended beyond her household, it was considered noteworthy, as in the case of Cornelia, the mother of the notorious political activists Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus.

As the daughter of the famous general Scipio Africanus, Cornelia (c. 190-115 BCE) was close to the epicenter of Republican politics in the 2nd century BCE. Through her nurturing and support of her sons, she achieved unprecedented public prominence, including a public statue. She was celebrated for her virtues and for embodying the ideal matrona: chaste, modest, loyal to her family, and devoted mother.

Cornelia can be contrasted with another woman who was prominent in Rome for a period, the Egyptian queen Cleopatra, whom Julius Caesar brought to Rome as an honored guest. This publicly powerful woman from the east was described by Plutarch in the 2nd century CE as a master manipulator who used her sexuality to manipulate the men around her for her own purposes.

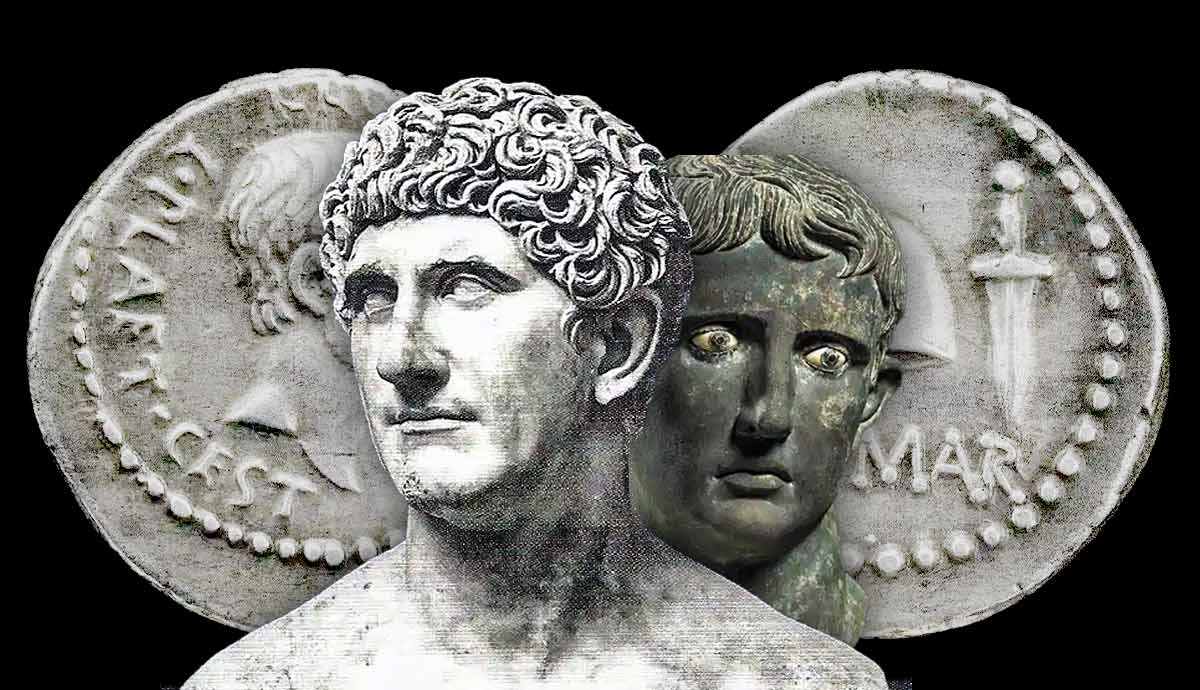

In the civil war that ensued between Mark Antony and Octavian following Caesar’s death, Antony’s relationship with Cleopatra gave Octavian plenty of ammunition. She was characterized as a decadent eastern queen who had corrupted a Roman general, and nothing like the virtuous women of Rome embodied by Cornelia. When Octavian became Augustus and the paterfamilias of the Roman state, virtuous women of the imperial family resembled Cornelia, but there was more than one “Cleopatra” in the mix.

Virtuous Matron: The First Empress

Rome’s first empress, Livia, the wife of Augustus, became something of an archetype for the women who followed. She was lauded publicly for her feminine virtues and, perhaps surprisingly, reportedly supported her husband Augustus in a handful of his political endeavours. Whereas Cornelia was a trailblazer with her single statue, Livia’s likeness appeared across the empire during her lifetime, from statues to coins. Her name was also given to prominent public buildings, such as the Porticus Liviae on the Esquiline Hill.

Nevertheless, there were clear limits to Livia’s agency and power. In a surviving letter from Augustus to the people of the island of Samos, he regretfully informs the Greeks that he cannot grant them the freedoms they had desired, despite his wife Livia arguing their case. The letter demonstrates how Livia could fulfil a public role as the patrona for a community, which was extraordinary for a Roman woman, but ultimately had no official power.

Livia actually became more powerful after Augustus’ death. Livia was an aristocratic daughter of the Claudian gens, but was now adopted into the Julian gens by Augustus, given a third of his property, awarded her the title Augusta, making her Julia Augusta. This protected the position she enjoyed under Augustus, and since Tiberius remained unmarried while he was emperor, there was no other woman to challenge her position. In addition, Tiberius infamously spent much of his time away from Rome, giving his mother significant power in the city in his absence. This led to the characterization of Livia as a domineering dowager during the reign of her son.

The Problematic Princess: An Alternative Stereotype

Under Augustus, Livia enjoyed prominence as his wife and matron of the imperial family, but she was not the only female member of the Julio-Claudian clan to receive public attention. A number of female family members appeared in a procession on the Ara Pacis, an altar to peace dedicated on Livia’s birthday, January 30, in 9 BCE. Among other things, it depicts a public religious procession that took place in 13 BCE to celebrate Augustus’ military victories, which brought peace to the empire. While the relief is not complete, scholars have identified Livia, Antonia the Elder, the daughter of Mark Antony and Augustus’s sister Octavia, and also Augustus’s only daughter, Julia, whom he fathered with his previous wife Scribonia.

Julia was very important to Augustus’s dynastic plans. He first married her to his nephew Marcellus, who Augustus was grooming as his heir until his unexpected death in 23 BCE. She was then married to Augustus’s friend and right-hand man, Agrippa, who became the new heir apparent. Together, they had two sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar, and Augustus prepared the youths as successors following Agrippa’s death in 12 BCE. At the same time, Augustus forced Livia’s son, his stepson, Tiberius, to divorce his beloved wife, Vipsania, and marry Julia to mark him out as the interim heir until his young grandsons came of age. While Julia may not have appreciated being repeatedly married off as part of Augustus’s dynastic plans, her importance is clear.

But while Livia had the reputation of the ideal matron like Cornelia, Julia was more of a Cleopatra figure. While she was considered glamorous and intelligent, she was also accused of promiscuity, adultery, and decadence. This eventually led to her exile for adultery and treason in 2 BCE. Both of these stereotypes, the supportive, chaste matron or the ambitious, promiscuous woman, would appear again and again throughout imperial history.

(Un)Happy Families: Empresses & Imperial Succession

Many subsequent empresses align with the Livia or Juli stereotype, or something in between. Claudius’ third wife Messalina, the mother of his son Britannicus, was also convicted of adultery and treason. This made way for Claudius to marry his own niece, Agrippina, keeping imperial power in the family. She was portrayed as ruthlessly ambitious, doing away with Claudius at just the right moment to ensure that her son from a previous marriage, Nero, succeeded before Britannicus could come of age. She was then as overbearing as Livia. But while Tiberius tolerated his mother, Nero had Agrippina assassinated.

More than half a century later, Plotina, the wife of Trajan, appears originally to have desired to be recognized as a kind of moral counterpart to her husband, who would be vaunted as the optimus princeps (‘the best emperor’). She displayed her lack of ostentation by rejecting the title of Augusta for over a decade after Trajan granted it to her in 100CE. However, the couple never had a son of their own. Instead, they adopted Trajan’s first cousin, Hadrian. This approach would go on to characterise the next several decades of imperial succession, leading to Rome’s Pax Romana, a relative golden age. Plotina’s heavy involvement in Hadrian’s succession did not pass with sceptical comment from some historians. A later tradition would even suggest that Plotina herself was responsible for Hadrian’s accession after Trajan’s death.

The celebration of imperial succession often proved a false dawn. In the early 3rd century, the matriarch of the Severan imperial dynasty, Julia Domna, was celebrated as the guarantor of “happy times” (felicitas saeculi) on coinage, because she was the mother of two sons who, in time, would succeed their father. Unfortunately for Julia, her sons Caracalla and Geta had a violently fractious relationship, resulting in fratricide.

Mater Patriae: Mother of Rome

Whether successors were chosen through birth or adoption, significant evidence survives for the role of the empress as mater (mother). On coinage, the Augusta might be paired with recognisable feminine virtues, such as piety, modesty, and fecundity, linked with the ideal matrona. Beyond coinage, Faustina the Younger, the wife of Marcus Aurelius, was commemorated on inscriptions as mater castrorum, the “mother of the camps.” This extended her matronly role to the imperial army.

The Augustae that came after Faustina the Younger enjoyed many extravagant titles that celebrated their maternal capacities. Alongside their roles as mater castrorum, they were called mater senatus (mother of the senate), and even mater patriae (mother of her country), a striking counterpart to the emperor’s traditional role of pater patriae.

The latter two titles in particular are associated with the Julias of the Severan dynasty: Julia Maesa, Julia Soaemias, and Julia Mammaea. For a long time, these women have been vilified for their apparently pernicious influence on imperial power between 217 and 235 CE. While their political power appears to have been significantly overstated, they nevertheless appear to have wielded significant influence behind the scenes.

Conspirators: Empresses as Kingmakers

Maesa was the elder sister of Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus. After the assassination of Caracalla in 217, Maesa concocted a conspiracy against the new emperor, Macrinus, to restore her family to the summit of Roman imperial power. She claimed that her grandson, the 14-year-old son of Soaemias, was actually the illegitimate son of Caracalla and, therefore, the rightful heir. A claim she reinforced with a generous donation to the soldiers. This successfully installed the emperor known as Elagabalus, but his eastern customs proved unpopular in Rome, including the prominence he afforded the women of his family in his court, especially Maesa and Soaemias. Although the Historia Augusta’s claim that he created a “female senate” is surely an invention, it does appear that the women of his family enjoyed significant prominence.

A palace coup followed, in which Maesa appears to have sided against Elagabalus, despite her role in his rise. The teenage emperor was murdered and replaced by his even younger cousin, Alexander, the son of Julia Mammaea. According to the ambivalent historical tradition that developed around Alexander, while he was a good emperor, he could not escape the overbearing influence of first his grandmother, and then his mother. This apparent weakness left him unable to sustain the loyalty of his soldiers. They revolted in 235 CE, opting for the professional soldier, Maximinus Thrax, over the “mummy’s boy.” Mammaea was killed with her son in a military camp on the German frontier, a testament to her central role in imperial power.

Victims: Empresses & Imperial Downfall

The fates of the later Severan empresses demonstrate another way in which the political importance of the Augustae was revealed: they suffered the same fate as the emperor husbands. Both Julia Soaemias and Julia Mammaea were not only executed in the plots against the emperor, but they suffered the same damnatio memoriae, with their names and images expunged from many public monuments.

Before this time, for an empress to be murdered alongside her husband was uncommon but not unheard of fate. The first to fall foul of this was Caesonia, the wife of the emperor Caligula. When Caligula was struck down in 41 CE, the rampaging praetorians also murdered his wife and young daughter. The emperor’s wife and child might just have been at the wrong place at the wrong time rather than deliberately targeted. In contrast, when Domitian was assassinated for his perceived tyranny, his wife Domitia Longina was spared. Neither Caesonia or Domitia seems to have enjoyed particular power or prominence when compared to their predecessors or successors.

Gods & Saints: The Afterlives of Empresses

“Oh no, I think I’m turning into a god!” quipped the emperor Vespasian as he lay dying in 79 CE. Tongue-in-cheek though it might have been, he must have known that he, like several of his predecessors, was to be deified by the Roman state and worshiped across the empire after his death. This practice became entrenched in imperial ideology from the Julio-Claudian dynasty, and both emperors and empresses would enjoy deification.

While Augutus was deified immediately following his death in 14 CE, Tiberius would block the deification of his mother Livia when she died in 29 BCE, apparently wanting to reserve the supreme honor for Augustus. She would later be deified by Claudius in 42 BCE, who honored his grandmother as a way to legitimize his own position. But she was not the first imperial woman to be deified, with Caligula deifying his beloved sister Drusilla following her untimely death in 38 CE.

These early acts established a precedent that allowed later emperors to freely deify the female members of their family. In the Forum Romanum, the emperor Antoninus Pius ordered the construction of a vast temple to the cult of his wife, Faustina the Elder, which still dominates the center of the ancient city today.

Empresses in the Christian Empire

When the Roman Empire converted to Christianity in the early 4th century CE, the empresses continued to remain significant. Ideologically, they continued to be linked to ideas of succession, and therefore to notions of stability and continuity. They were also celebrated for their virtues. Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, was recognised as Augusta in 325 CE. Thereafter, she embarked on a series of celebrated spiritual endeavours. Most famously, she undertook a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, where she uncovered the remains of the True Cross and led the construction of a number of churches, including the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem. The fragments of the True Cross were brought back to Rome, where they can still be seen in the Church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme.

A statue of Helena, depicting the empress seated, is said to have been inspired by the statue of Cornelia, the paragon of maternal virtue from the Republican era. In a new, Christian era, the empresses still lacked official political power in a patriarchal society, but held a different kind of sway both politically and ideologically.