Summary

- The Cimbrian War (113-101 BCE) was Rome’s gravest threat since Hannibal, as Germanic tribes invaded Italy.

- Early Roman efforts faced disastrous defeats, including the annihilation of forces at Noreia and Arausio.

- Gaius Marius, an ambitious general, was illegally re-elected consul multiple times to lead the war.

- Marius ultimately secured decisive Roman victories at Aquae Sextiae and Vercellae, ending the Cimbrian threat.

In the middle of the 2nd century BCE, the Roman Republic had fought and won several overseas wars. Carthage had been decisively defeated in the Third Punic War, while the Greeks and Macedonians in the east had also been brought to heel. However, by the end of the century, war reached the Italian peninsula. For the first time since Hannibal had ravaged the peninsula, an enemy had brought the fight to the Romans: the Cimbri. While the Cimbrian War (113-101 BCE) posed a grave threat to Rome itself, it also provided the ambitious general Marius with the opportunity to solidify his position as Rome’s greatest general.

Rome on the Eve of the Cimbrian War

In the years that preceded the Cimbrian War, the attention of the Roman Republic had begun to turn inward. During the early and middle decades of the 2nd century BCE, a series of decisive foreign wars had been fought, and Rome’s victories cemented her primacy in the Mediterranean world.

The Seleucids had been defeated, Carthage had been obliterated during the Third Punic War, and the Achaeans and the Macedonians had been brought to heel. In the years that followed, internal political tensions came to the fore. There was a divide in Republican politics between the populares, who represented the interests of the people more widely, and the optimates, who represented the established, senatorial aristocracy.

These tensions had erupted into violence, most notoriously with the murder of Tiberius Gracchus, a populist (or political agitator, depending on which faction you asked). Elected as Tribune of the Plebs, Tiberius used the platform provided by his magistracy to propose sweeping changes, including land redistribution. He also used his power of veto to block legislation. Tensions erupted into violence in 133 BCE, and Tiberius was murdered by a senatorial mob led by Publius Cornelius Scipio Nasica.

It proved to be an unhappy period for the Gracchi, as Gaius chose to follow in his elder brother’s footsteps. Although their mother, Cornelia, was upheld as a paragon of Roman matronly virtue, Gaius, like Tiberius, was murdered as a political agitator in 121 BCE. It was during this swirling maelstrom of political violence that the Republic once more found itself at war, this time against the Cimbri.

A People at War: Who Were the Cimbri?

The Cimbri were a people who lived in the Jutland peninsula in northern Europe. These Germanic people would, in time, become “friends” of the Romans. According to Augustus’ Res Gestae, the Cimbri were one of several Germanic peoples who sent envoys to seek the approval of the first princeps. The famous Gundestrup cauldron, an especially ornate silver vessel discovered in Denmark, is possibly a work of Cimbrian art. Significantly, the iconography on the cauldron suggests that the Cimbri were part of the La Tène culture.

Late in the 2nd century BCE, the Cimbrians (along with the Ambrones and the Teutons) migrated southeast en masse. As they traveled, their numbers were swollen by defeated Celtic groups who joined their ranks; this included the Scordisci and the Boii. In around 113 BCE, they entered Noricum (roughly modern-day Austria and Slovenia), where they invaded the territory of the Taurisci. This Celtic group had been allied with the Romans, to whom they turned for aid. The stage was set for war.

Early Roman Defeats

To begin with, the Romans dispatched the consul, Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, to Noricum. With the legions that accompanied him, the plan was ostensibly to put on a show of strength to deter the Cimbri from further incursions into allied territory.

The Cimbri did initially comply with Roman demands. However, they soon discovered that Carbo had attempted to ensnare the invaders in an ambush. It is possible that Carbo foolishly thought the Cimbri and their allies offered an easy opportunity to claim a Triumph for successful military action. However, the Cimbri were enraged by this treachery, and they attacked the Romans.

Foreshadowing the early course of the war, the Battle of Noreia in 113 was a disaster for the Romans. The Roman army was annihilated, and Carbo only narrowly escaped with his life. He perhaps should have stayed with his men; later, he would be prosecuted for his failure by Mark Antony, and unable to accept the punishment of exile, he killed himself.

The temporary saving grace for Carbo was that the Cimbri did not immediately follow up on this victory. Instead of advancing on Italy, they went west, over the Alps and into Gaul. Along the way, additional groups of Celtic peoples joined their armies. Again, the Roman forces sent to defeat these growing ranks were crushed. The Republic was battered when the legions marched to drive the invading Cimbri out of Gallia Narbonensis in 109 BCE, and another defeat followed two years later when a Roman commander, Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravalla, was slain at the Battle of Burdigala.

Disaster at Arausio

The lowest point for the Romans would come in 105 BCE. Another Roman army marched northward and established a camp on the Rhône River (near Orange, a town famed today for its Roman remains). The consul, Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, and the proconsul, Quintus Servilius Caepio, were not an effective team. The hostility between the two would prove disastrous. Nevertheless, they were able to put into the field the largest Roman force seen since the Second Punic War, when the Republic had been mobilized against the genius of Hannibal.

With over 80,000 men under their command, the Romans foolishly divided their forces across the two banks of the river, and both forces were wiped out. Caepio’s overconfident attack was the first to be destroyed, and this left the consul’s camp undefended. In the end, only a few hundred Romans were able to escape.

This battle at Arausio was the worst Roman defeat since the massacre at Cannae. Again, however, the Cimbri did not press home their advantage. Instead of rounding on the Italian peninsula, they advanced into Spain. There, they would suffer the first reverse since they had departed their homelands in Jutland. The disaster at Arausio also focused Roman minds. Political antagonism at home was set aside (temporarily, at least), and the rules regarding multiple consulships were eased, allowing a new man to lead the fight.

The New Man: Gaius Marius

In the aftermath of Arausio, the Republic was in a state of terror. The expectation was that the Cimbri would imminently appear at the city gates. Desperate times called for desperate measures. Gaius Marius, a novus homo (“new man”), was re-elected to the consulship in 104 BCE. In an unprecedented and highly illegal move. The law was that magistrates had to wait ten years between consulships, and Marius had previously served as consul in 107 to lead the forces in Numidia to victory in the Jugurthine War. But Marius’s success in North Africa while Rom was suffering defeats on other fronts had many believing that he was the only man capable of dealing with the Cimbrian threat. Rome would continue to bend the law to appoint Marius as consul every year from 104 to 100 BCE so he could continue to conduct the war.

Marius only headed to Gaul after celebrating his triumph over Jugurtha in Rome in 104 BCE. With the future dictator Sulla as his legate, Marius established a base at Aquae Sextiae (modern Aix-en-Provence). With the Roman army decimated, Marius ignored traditional Roman recruiting practices, which only called on landed citizens, and recruited veterans and unlanded Romans to fight. This allowed him to raise of force of around 30,000 Romans and 40,000 Italian and allied troops. Marius was in no rush to engage the enemy; instead he trained his new men.

The Cimbri were a big enough threat that Rome was willing to give Marius time, and he was re-elected as consul in absentia in 103 BCE, even though he could have continued his command as proconsul. But in 103 BCE, Marius was still forced to return to Rome to oversee consular elections for the following year because his colleague had died in office. Despite not yet making any progress against the Cimbri, he was re-elected yet again in 102 BCE, when he would finally march out to claim Rome’s revenge.

Marius Turns the Tables

The campaign conducted by Marius against the Cimbri was methodical and calculated. The Cimbri, whose numbers were now supplemented by additional Celtic groups (such as the Helvetians), divided their forces.

One group would march into Italy from the north-east, the other through the north-west. Marius, having made camp at the confluence of the Isère and Rhône rivers, merely observed the enemies’ movements. Marius and the Romans followed cautiously as the enormous invading army crossed into Italy. Soon, this patience would pay off.

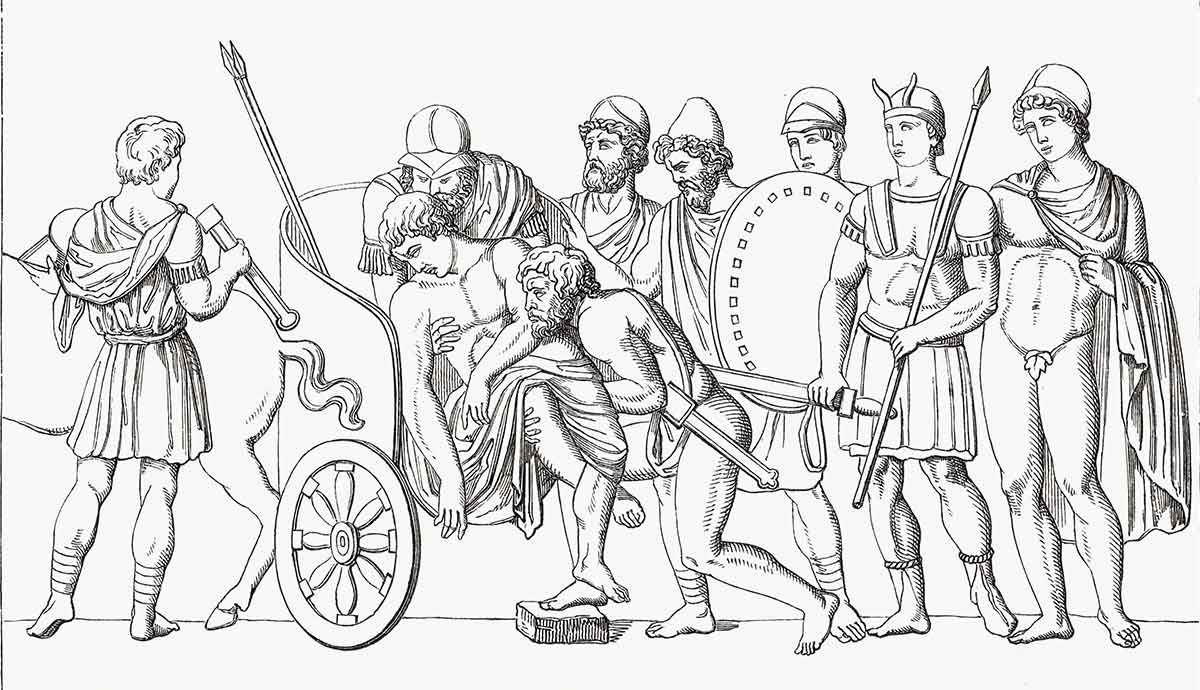

For reasons unknown, one group of invaders, the Ambrones, had separated from the Teutons. Inadvertently, a skirmish broke out between some of Marius’ camp servants who had gone to fetch drinking water and some bathing Ambrones, and this escalated rapidly into a full battle. Plutarch’s Life of Marius describes the slaughter of the Germanic tribe, with approximately 30,000 Germans killed.

The survivors rushed to join the remainder of their Teuton allies, who regrouped at Aquae Sextiae to await Marius’ army. The battle that followed was a crushing Roman victory. They had taken the initial advantage by fighting from high ground, while a detachment of five cohorts, hidden by Marius in a nearby wood, devastated the Germanic rear. The Teuton king, Teutobod, was captured while his armies were massacred. According to reports, Marius’ men killed 100,000 men. As reports of the victory reached Rome, Marius was elected consul in absentia again for 101 BCE.

Rome Triumphant: Victory at Vercellae

The battle at Aquae Sextiae crushed only half of the threat to the Roman Republic: the Cimbri were still at large and heading to Italy. By 101 BCE, the Cimbri were able to advance into the peninsula through unfortified Alpine passes. Again, however, they dawdled and missed their chance. Instead of advancing, the Cimbri stopped to plunder the rich territories of northern Italy. This gave Marius the crucial time needed to march north to engage the invaders.

Unfortunately for the Cimbri, he arrived with the six legions that had triumphed at Aquae Sextiae. Marius and his battle-hardened soldiers met the Cimbri at Vercellae, a plain near the confluence of the Sesia and Po Rivers. On the plain, the Cimbri were undone by the Roman cavalry, led by Sulla. While Quintus Lutatius Catulus (Marius’ co-consul) pinned the enemy in place with his legion, Marius himself flanked the Cimbri. The result was a devastating slaughter of the Cimbrians. Plutarch suggests that 120,000 were killed and a further 60,000 enslaved. The Cimbrian War was over.

The Beginning of the End? The Republic After the Cimbrian War

For the Cimbri, the end of the war was not the end of their history within the Roman world. As noted in the introduction, these people were still notable enough within the Roman consciousness in the early 1st century CE to warrant a place in Augustus’ Res Gestae. More immediately, it has been suggested that some of the captives taken in the aftermath of Vercellae were among those rebellious gladiators who joined Spartacus during the Third Servile War.

Back in Rome, Marius and Catulus, his co-consul in 101 BCE, who was leading the Roman troops stationed in Italy, shared a joint triumph for their victory at Vercellae. Marius was awarded an unprecedented sixth consulship in 100 BCE, his fifth consecutive, and the Republic appeared to have been saved. However, the lasting damage caused by the Cimbrian War would prove, in time, to have been internal. Tensions that had been festering for some time before the conflict were exacerbated, and bloody civil violence would soon break out on scales hitherto unknown in the Roman world.

In particular, the Cimbrian War served to escalate tensions between the two great Roman military commanders of the age: Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla. In 88 BCE, when war broke out with Mithridates of Pontus, despite now being 70 years old, Marius wanted the command. However, it was his former legate, Sulla, who was elected consul and received the command. Marius still tried to take the command, executing political maneuvers that led to riots in Rome and delayed Sulla’s departure. The situation would only be resolved by Marius’ death, apparently due to natural causes, in 86 BCE.

Sulla successfully conducted the war, and when he returned to Rome in 82 BCE, he had himself declared dictator to make constitutional reforms to prevent the kind of political maneuvering that had delayed his start to the campaign. These changes would not matter. Both Marius and Sulla made it clear that, with Rome’s expanding empire, military strongmen now held political sway. They paved the way for other Roman generals to exercise almost absolute power in Rome, including Gnaeus Pompey and, of course, Julius Caesar.