What is it about the story of Salome and John the Baptist? Art depicting Biblical scenes may have been less prevalent by the mid-19th century, but this tale of a scandalous young princess had a sudden vogue in French art and literature. A craze for Salome’s daring dance and demands swept over the nation, and before long, she was scandalizing audiences further afield, too.

The Story of Salome and John the Baptist

The story of Salome and John the Baptist is told in the Bible’s New Testament, in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew. King Herod II (or Herod Antipas) has imprisoned John the Baptist, the prophet who baptized Jesus Christ. John the Baptist has been going about Herod’s kingdom spreading dissent: casting out devils, anointing the sick, and urging sinners to repent.

It’s not only Herod who fears John the Baptist. His wife, Herodias, was previously married to Herod’s brother Philip, and John the Baptist has branded this marriage unlawful. Salome, Herodias’s daughter from her previous marriage, shares her mother’s ire for the prophet.

The climax of the story, and the scene which most interested subsequent artists, comes when Herod throws a birthday feast. The King James Bible passage from Mark’s Gospel runs:

“And when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee.”

Salome consults with her mother, and they ask for John the Baptist’s head. Herod sends an executioner to the prison and presents his stepdaughter with the prophet’s head on a platter.

Matthew’s Gospel tells the story similarly. Neither Gospel identifies Herodias’s daughter by name as Salome, and in some translations, she was also known as Herodias. Later texts, however, name Salome as the stepdaughter of Herod Antipas.

Salome in Renaissance and Baroque Art

This grisly story fascinated artists at a time when Biblical stories made up the majority of subjects for painting. The Old Masters were no strangers to depicting scenes of extreme violence. In some cases, representations of Salome with John the Baptist’s head have been mistaken for representations of a similar scene of female violence from the Bible: Judith beheading Holofernes.

These paintings tend to show Salome from the waist up, clutching a platter with the head of John the Baptist on it. Usually, Salome appears unrepentant, even innocent, in stark contrast to the horrific sight of the severed head.

It was less common (though not unheard of) for painters to depict the scene as a whole, showing Herod’s feast and all his guests. Depicting Salome alone was an opportunity for painters to execute half-length portraits using well-to-do women of the day as models.

Titian, in the early 16th century, made at least three paintings of Salome with the head of John the Baptist throughout his life. There is debate as to whether his painting of the subject circa 1515 in fact depicts Herodias, Salome’s mother, or perhaps Judith and Holofernes.

Guido Reni also painted the subject in 1638-39 and again in 1639-42. The earlier painting is notable as Salome wears a turban to suggest her derivation as a princess of Galilee. The second painting shows her daintily holding up her skirts in evocation of the dance she has just performed for the king.

Also in the early 17th century, Caravaggio painted the subject multiple times. His two paintings, titled Salome with the Head of John the Baptist (c. 1607 and c. 1610), show Salome and the platter, along with her maidservant and the executioner. Nor were these the only beheading scenes that captured Caravaggio’s imagination. Around this time, he executed paintings of Judith beheading Holofernes and David’s victory over Goliath, the high drama of each scene accentuated by the painter’s tenebrism, or use of extreme light and dark.

The Salome Vogue in France

Representations of Salome in visual art continued through the centuries, but in mid-19th-century France, she found herself at the center of an explosion of artistic activity that ranged across various art forms.

Painter Gustave Moreau and author Gustave Flaubert worked on their depictions of Salome in the same period, the mid-1870s. Both shift the viewer’s—or reader’s—focus from the horror of John the Baptist’s execution to the intrigue of Salome’s dance and its enchanting effect on Herod, who promises Salome anything she wants as a result of this dance.

Flaubert’s story Hérodias appeared in a collection called Three Tales in 1877. In his version, both the dance and the execution are part of a master plan concocted by Herodias because of her hatred for the prophet. She encourages her daughter to dance seductively for Herod so that he will grant her any wish.

The emphasis in Flaubert’s tale on Salome’s dance proved influential on stage productions of the scene. The first of these was the opera Hérodiade by Jules Massenet, first staged in 1881 with a libretto based on Flaubert’s story and an accompanying ballet suite. As well as indicating the artistic allure of the idea of Salome’s dance, Massenet’s opera introduced an important angle to the story by toying with a romance between Salome and John the Baptist.

Moreau, meanwhile, worked on paintings of Salome from the late 1860s, ultimately exhibiting Salome dancing before Herod and The Apparition in 1876. In these and an early, abandoned version titled Salome Tattooed, the viewer’s eye is drawn to Salome’s dancing body, robed in rich jewels, and pointing towards the right of the painting. In The Apparition, Salome points at John the Baptist’s head, which hovers in the air, ringed by a halo.

These paintings are typical of Moreau’s style and of the Symbolist movement he formed part of. The backdrop of Herod’s palace is incredibly ornate, and the paintings seem to glow, both with the jewels on Salome’s person and with a sense of divine mystery. In common with much Symbolist work, the paintings are both richly detailed yet suggestive rather than meticulously defined. They also draw our attention to the scene’s eroticism and (like Flaubert’s version) make Salome’s dance the focal point of the story.

As the title The Apparition suggests, Moreau depicted the scene as a dream or vision, with John the Baptist’s head floating eerily and Salome pointing to it in an oblique gesture. Is she triumphant or disturbed? Perhaps both, as subsequent artists in the Symbolist and Decadent traditions imagined. Stéphane Mallarmé wrote a poem based on Moreau’s painting in which Salome takes perverse pleasure in relishing the “horror” of her virginity and musing perversely on the allure of death.

Joris-Karl Huysmans, in his influential novel À rebours (1884), had his decadent protagonist Des Esseintes luxuriate in owning two masterpieces by Gustave Moreau, one of which is certainly The Apparition. Huysmans gives a long, detailed description of the painting, and the “maddening charms and depravities of the dancer” which had remained latent in the Bible story, until Moreau had brought them to the surface.

Huysmans defines Moreau’s Salome in a passage which effectively sums up the Victorian concept of the femme fatale or dangerous female beauty, which fascinated so many (mostly male) artists of the period:

“the symbolic deity of indestructible lust, the goddess of immortal Hysteria, of accursed Beauty, distinguished from all others by the catalepsy which stiffens her flesh and hardens her muscles; the monstrous Beast, indifferent, irresponsible, insensible, baneful, like the Helen of antiquity, fatal to all who approach her, all who behold her, all whom she touches.”

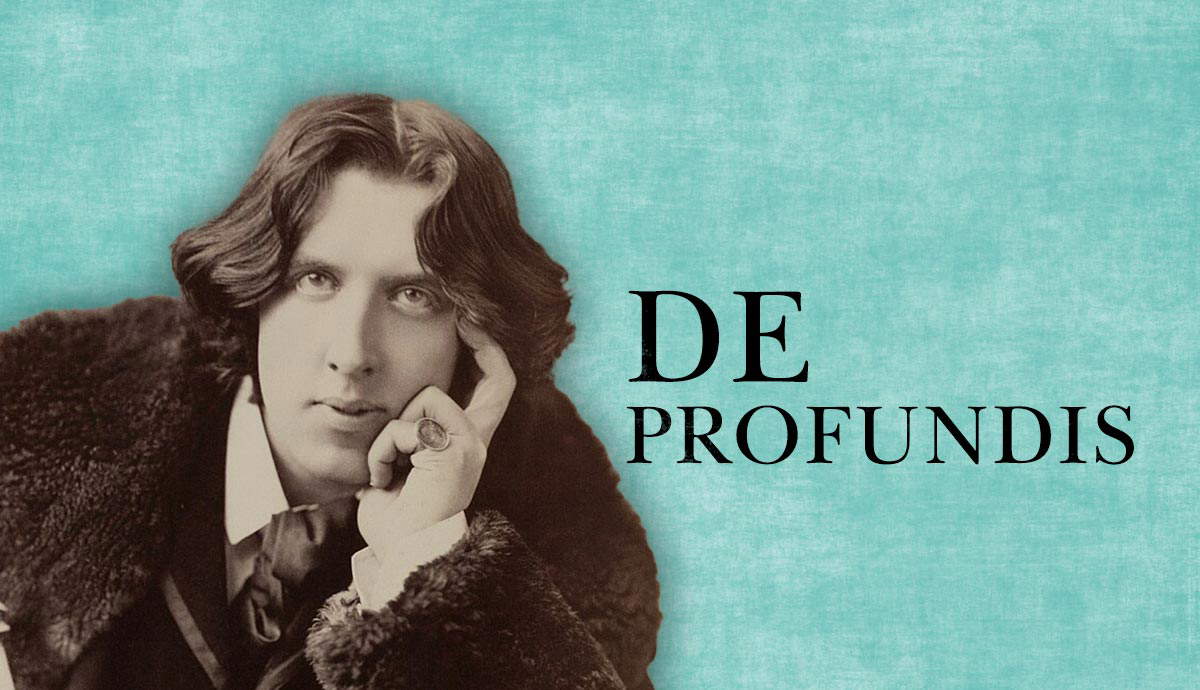

Salome retains this evil significance for another artist, who viewed Moreau’s painting at The Louvre in 1884, the same year that he read Huysmans’s À rebours (which would inspire his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray): Oscar Wilde.

Salome Beyond Art and Literature

With his play Salome (1891), Oscar Wilde brought two French imports to English shores: Symbolist writing and the Salome craze. He even originally wrote the play in French. Wilde’s language in this play was starkly different from that of his other writing. The play focuses on motifs such as the paleness of Salome’s skin, the haunting glow of the moon, and the shared redness of Salome’s lips and John the Baptist’s blood.

Herodias, jealous and fearful of her daughter’s allure, repeatedly insists to her husband that he must not look at her, and indeed, multiple characters try to avoid looking at Salome, so ruinously seductive is the sight of her. The play also trains the audience’s attention on John the Baptist by placing his prison cell centrally on stage. His booming voice periodically interjects, prophesying the second coming of Christ and urging his imprisoners to repent.

Wilde emphasizes the idea of Salome’s attraction to John the Baptist in Massenet’s operatic version. Salome repeatedly tells him, “I will kiss thy mouth.” However, this attraction turns out to be perverse: it is only when his head is severed that Salome kisses his mouth.

Wilde’s most important addition to the Salome story was the Dance of the Seven Veils. In Flaubert’s Hérodias, one of Wilde’s sources, Salome dances on her hands in the manner of popular ‘Eastern’ dancers of the 19th century. Wilde, however, takes the minimal information about the dance from the Biblical account and combines it with Moreau’s and Huysmans’s visions of Salome as an exoticized femme fatale.

Wilde’s stage direction does not specify what the Dance of the Seven Veils entails, but it has generally been performed as a kind of striptease in which Salome removes seven veils one by one. When Wilde wrote the play, Western dancers were beginning to perform their own versions of what they considered Middle Eastern dances using veils, such as Loie Fuller’s dance in a version of The Arabian Nights in New York in 1886.

Salome then made her way to other arts, such as illustration, with Aubrey Beardsley‘s drawings based on Wilde’s play. One of his best-known illustrations shows Salome holding John the Baptist’s head aloft, ready to kiss. Although Salome is far more covered up in Beardsley’s depictions than in Moreau’s (her dress often occupies a vast swath of the page), the drawings are no less scandalous. Wilde had taken the subversive potential of the Salome story as it appeared in French art and literature, and added further layers of psychosexual intrigue.

Salome on Stage and Screen

With Wilde’s play, Salome became a more contentious subject than it had been during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, when painters would show the grisly aftermath of her demands, but not the seductive means she employed to get what she wanted.

Wilde’s Salome could not be staged in Britain due to a ban on depicting Biblical subjects, and Wilde himself never saw the play on stage. This was all the more devastating as Wilde had specifically hoped to see it performed with the legendary French actress Sarah Bernhardt in the leading role. As it was, the first performance was in Paris in 1896, with a different actress, while Wilde was serving his prison sentence.

There was further controversy around Wilde’s Salome regarding its English translation, which Aubrey Beardsley had hoped to provide, but which Wilde allowed his lover Lord Alfred Douglas to complete instead. Writing to Douglas from prison, after run-ins with Douglas’s family had led to his trials and imprisonment, Wilde lamented this decision, branding Douglas’s translation unworthy of him and of the play.

With Salome still banned in Britain, it was left to European theater companies to stage the play. One of these, in Berlin in 1902, caught the attention of the composer Richard Strauss, who recognized how well Wilde’s musical language, with its repetitive motifs, could be adapted into an opera.

Strauss’s Salome premiered in 1905 and attracted as much scandal as Wilde’s, if not more. The deeply provocative Dance of the Seven Veils was now combined with music which struck many listeners as simply too avant-garde for their delicate ears. Strauss’s post-Wagnerian use of leitmotifs, chromaticism, and dissonance was simply inappropriate for a Biblical subject, many felt. Never mind that Strauss often employed these techniques with cunning effect to emphasize the scene’s horror, such as the dissonant chord at the very end of the opera when Herod demands Salome be killed.

The lead role in Strauss’s Salome called for proficiency in both singing and dancing. However, in 1906, a Canadian dancer decided to stage a version of Salome inspired by Wilde’s and Strauss’s versions but focusing on the Dance of the Seven Veils.

When Maud Allan’s The Vision of Salome came to London in 1908, it embroiled the Salome story in even further scandal. Not only was it still forbidden to stage Biblical stories, but Allan included a horrifyingly realistic wax head of John the Baptist in her production, and most shocking of all, danced topless, her upper half covered only by jewelry.

Allan was the most notorious popularizer of the Salome vogue in the early 20th century, especially for audiences across America. But in Britain, she faced accusations of leading the public astray—despite this accusation coming as a result of a private performance. Allan was playing Salome in a 1918 production of Wilde’s play, for which audience members had to apply, making the performance technically private and therefore legal.

Nevertheless, MP Noel Pemberton-Billing, on hearing about Allan’s provocative rendition of the Dance of the Seven Veils, wrote in an article that she was promoting the ‘Cult of the Clitoris.’ Such dangerously seductive performances (which Billing decided must be the result of the involvement of homosexuals in the arts) were especially dangerous in times of war, as in 1918. For all he and the public knew, Allan could be a German conspirator, undermining the moral health of the nation.

Allan sued Billing for libel, and Wilde was again dragged into the courtroom—albeit now posthumously. Billing was found not guilty, Wilde’s play was condemned along with all of his other output as morally degrading, and Salome remained a contentious subject.

Whether in new stagings of Wilde’s and Strauss’s works, in film versions starring femmes fatales of the day such as Theda Bara (in 1918) or Rita Hayworth (in 1953), or in arresting visual depictions by Salvador Dalí and Francis Picabia, Salome has retained her power to shock and fascinate in equal measure.