Discussions of warfare in ancient Greece and Rome usually revolve around open field battles with dense formations of infantry clashing, supported by cavalry and missile troops. But many ancient conflicts were resolved through sieges, with enemy armies attempting to breach a city’s wall while starving those barricaded inside. Sieges required special tactics and weapons, and generals needed both patience and ingenuity to successfully break a siege.

City Walls and Defenses

Siege warfare was baked into the very culture of ancient Greece. The most famous story of the ancient Greek world, the Trojan War, tells the tale of a protracted siege between the Achaeans and the Trojans. Siege warfare in this era, presumably the late Bronze Age, seems to have revolved around skirmishes outside of the city walls, with little in the way of siegecraft. The fact that the war lasted for 10 years, with the Trojans continually receiving reinforcements, implies that completely blockading the city was probably not even considered.

After the Bronze Age Collapse, the Greeks still relied heavily on stone walls for protection. Greece at the time was not a united political entity, but rather a collection of city-states that were almost constantly at war with one another. These defenses were simple constructions of stone that ringed a settlement. In later centuries, towers were added, increasing the vantage point of the defenders. Standalone towers and forts were also used to act as early warning systems. Walls were also used to mark territorial boundaries. The Phocians built a wall at Thermopylae to ward off Thessalonian raids, which were rebuilt by the Spartan King Leonidas in response to the Persian invasion. Walls were also built to protect lanes of travel, such as the famous Long Walls, which connected Athens to the port of Piraeus, a distance of about four miles.

The most common tactic to capture a city was to blockade the target, cutting it off from supply and starving the defenders out. This is a double-edged sword, however, as the besiegers would be forced to live off the land, and with limited logistics networks, they were just as likely to run out of supplies. Another strategy would be to lay waste to the surrounding area, provoking the defenders into leaving the safety of their fortifications and fight an open field battle, negating the need for a siege to begin with.

Rams, Ramps, and Flamethrowers

When the enemy was too stubborn to fight in the open field, and waiting to starve them out was not an option, there were other methods to capture a city. The battering ram was a long tree log, often with a bronze ram’s head at the end, which was designed to batter down the enemy’s walls or gateway. The first rams were simply held by a group of men and slammed into the fortification. Later versions were suspended from a wooden frame by chains, which allowed it to gain more momentum with each swing. A surviving ram head from the 5th century BCE has two rows of serrated teeth, which would imply that it was used to grip into the walls and tear out the stones rather than simply knock them over. This was made possible by the relatively thin walls of Greek cities.

If going through a wall wasn’t possible, another option was to go over it. Ladders could be used for this purpose, but there was another, more substantial method. A ramp could be constructed, made from stone and earth. It took a long time to construct an earthen ramp, but when it was completed, a besieger could simply walk over the walls. Another way to go over the top was the use of siege towers. These were wheeled, wooden structures that could be pushed against the wall, delivering the troops directly to their destination. The first known use of a siege tower by the Greeks was in 397 BCE by Dionysus I of Syracuse against Motya.

If going over the walls wasn’t an option, going under was another possibility. Undermining a wall meant digging a tunnel under the enemy’s wall, propping the earth above with wooden timbers. The space would be packed with straw or combustibles and set alight. The timbers would burn away, and the tunnel would collapse, bringing that section of the wall with it.

In 424 BCE, the Boeotians besieged the Athenian-held city of Delium and utilized the world’s first flamethrower. It was a hollowed out iron bound pipe with a bellows at one end. At the other end, hanging from chains, was a cauldron filled with pitch, sulfur, and tar that was set alight. When pumped, the bellows would force air over the burning cauldron, spraying flame over the target. Though it was awkward to use, it did manage to frighten the Athenian defenders and set the wooden towers on fire. Shortly after, the Boeotians stormed into the city, winning a decisive victory. In spite of this successful use, there are no further accounts of flamethrowers being used during the rest of the Peloponnesian War.

Siege Artillery

The first piece of Greek siege artillery was invented in the early 4th century BCE in Syracuse, Sicily, during the reign of Dionysus I. The weapon was a precursor of the crossbow, where a powerful bow was mounted on a wooden shaft. Called the gastrophetes, or “belly shooter,” it allowed the user to press the end of the weapon against his stomach, drawing the string and holding it in place with a series of ratcheted notches. It would then be shot by activating a trigger mechanism. It had the power to reach defenders on city walls.

The next big leap in siege technology was the use of torsion powered engines. Instead of using a bent bow, rigid arms would be fitted to a mechanical frame. Elastic ropes, usually made from animal sinew, would be wrapped around the arms, propelling them forward. The limiting factor of these torsion engines was the strength of the sinews providing the tension.

Very broadly, these torsion engines came in two main types, bolt or arrow throwers and stone throwers. Bolt throwers were used as anti-personnel weapons, and could be considerably accurate and powerful, capable of hitting a soldier atop a wall from hundreds of yards away. Stone throwers could be used against thinner walls and buildings and were often used to lob stones over the top of the walls into the buildings behind, an early form of indirect artillery fire. These engines could also be used defensively, mounted on walls or towers to thwart an enemy’s attempt to storm the fortification.

The culmination of Greek siegecraft came during the meteoric career of Alexander the Great. In 332 BCE, Alexander and his Macedonian army laid siege to the island city of Tyre. Since he lacked a sufficient navy, Alexander ordered his men to construct a causeway that stretched from the mainland to the island. Once in range, the city was bombarded by artillery and siege towers, which had catapults on them to clear the walls, were moved up. After a few setbacks, the rams were able to breach the walls, and the Macedonian army poured in, capturing the city after a lengthy siege.

Roman Siege Warfare

The siege techniques created by the Greeks were readily adopted by the Romans, who made siegecraft into an art form. The Roman army was well versed in fortifications by its very nature. While on the march, Roman soldiers would dig a fortified encampment, complete with defensive ditch and wooden palisade every night. With this level of experience in building defensive positions, dealing with strongholds was the Romans’ specialty.

The first way to capture a city or fortress would be to blockade the target and starve it out. Using their experience building a fortified camp every night, the Romans could build a wall around the city, completely cutting it off from supply or reinforcement. In some cases, such as at the siege of Alesia in 54 BCE, the Romans built a second wall around the first, protecting the besiegers from possible relief columns coming to the aid of the besieged. Like the Greeks, they ran the risk of running out of supplies before the enemy capitulated, but over time, the Romans had developed a sophisticated logistics system that kept the army running while dug in around an enemy’s stronghold.

While they waited for the enemy to starve into submission, they would employ a number of siege engines in order to demoralize the enemy and soften the target up before any potential assault. They made great use of ballistae, which used two rigid arms propelled by torsion to launch bolts or stones. The smallest ballistae, also called a scorpion, could be lifted by a small group of men, while others would be massive. Single arm torsion engines were also employed. These were named onagers, or wild donkeys, due to their tremendous kick. Both of these engines were used for anti-personnel purposes, and could be effective against thinner walls or wooden palisades, but had difficulty against thicker stone walls of more sophisticated settlements.

These siege engines were operated by a specialized class of soldiers. They received dedicated training to operate the ballistae and onagers and were considered part of the immunae, soldiers who had special skills and status that exempted them from digging ditches, latrine duty, and the other drudgery that was the lot of the common soldier.

How the Romans Broke Into Cities

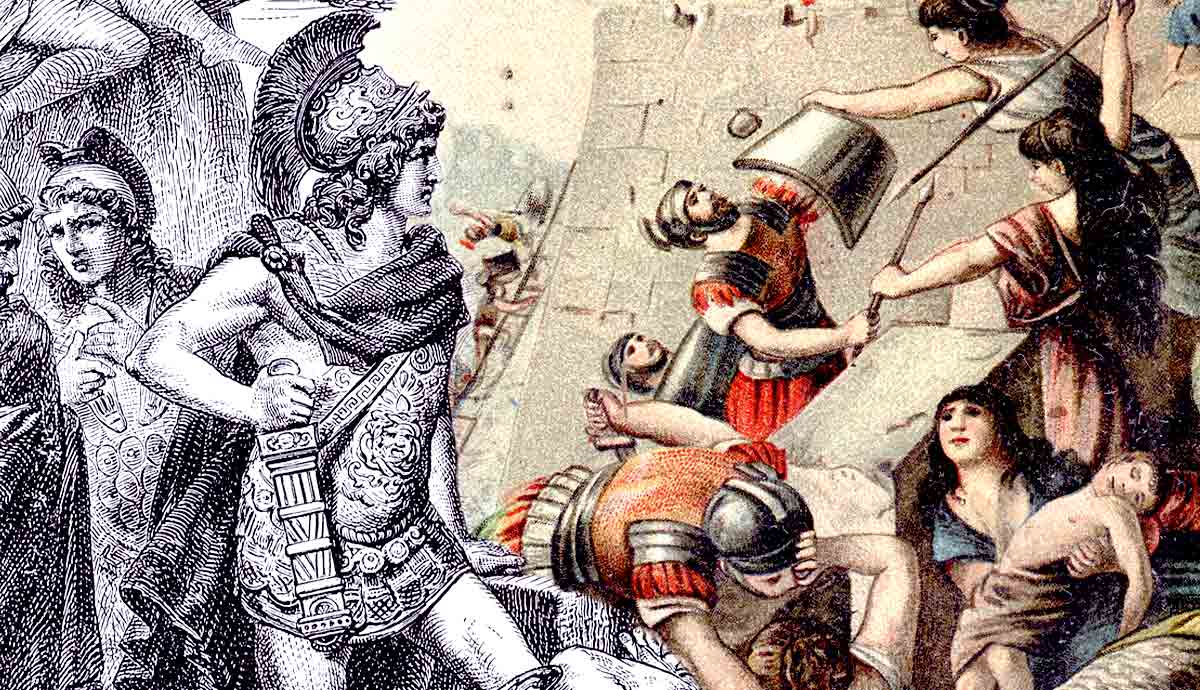

If a city could not be starved into submission, and the defenders too stubborn to submit to the constant bombardment of bolts and stones, a more direct approach was in order. Like the Greeks before them, the Romans could use any number of methods to get into a stronghold. These included the use of ladders, siege towers, and battering rams. In order to reach the walls or gate, legionaries employed the famous testeudo formation, in which they would interlock their shields, forming a roof over their heads. This protected them from the arrows, stones, and other missiles dropped on them from above. Once at the wall, they would use the battering rams to smash open the gate, letting the army in. Rams would be covered in animal hides soaked in water to prevent it from being set on fire by the defenders. They would also undermine the walls by digging under, once again employing specialized engineers for the task. The Romans also made use of earthen ramps to climb over the walls, as was seen at the famous siege of Masada in 73 CE.

Assaulting a city was done as a last resort, since even the highly trained and disciplined Romans were at a disadvantage attacking a fortified position. If a breach in the walls was made, it would be a natural choke point that the defenders could rally around. There was a risk of high casualties and taking a stronghold by force was not done lightly. It was so dangerous that one of the highest awards for valor in the Roman army was the Mural Crown, a decoration given to the first man to scale an enemy’s walls.

Because of the risks associated with storming a fortification and the inevitable casualties that would result, the Romans could be brutal with a captured settlement. To avoid bloodshed, the Romans would generally allow a city the chance to peacefully surrender at any time during the buildup, but once a piece of siege equipment, such as a ram, touched the walls, no mercy would be shown. In vengeance for the bloodshed caused by their failure to surrender, the wrathful legionaries would slaughter anyone they found, civilian or military, and even animals. Anyone who survived would be sold into slavery. While done out of blood-lust and pent up frustration being unleashed, it also served as a warning to any who would challenge the might of Rome.