As far back as the 9th millennium BCE, lapis lazuli, the metamorphic, azure-blue rock, was valued for its depth of color, often accompanied by flashes of gold pyrite. This combination—gold and deep blue—became the ultimate pairing in religious iconography and as a representation of wealth over centuries of art and culture. But what made lapis lazuli so precious, and why did it become so revered?

Lapis Lazuli: Rare and Precious

Found in the works of the ancient civilizations of the Indus Valley and the Badakhshan mines of Afghanistan dating back over 7,000 years, lapis lazuli has been recognized as a precious stone like no other. Although mined from the ground, it resembles nothing of the sort; its brilliant blue being compared more with the sea and the sky than the ochre earth of its origins.

Its name lapis derives from the Latin word for stone, with lazuli appearing in various Latinized forms—azul in Spanish and azure in French, for example, referring to the blue that so forcibly captured the imaginations of those who found it first. The rarity and natural beauty that lapis possesses has rendered it sacred to some civilizations. The Sumerians, in Mesopotamia around 6,000 years ago, believed lapis lazuli could deter sadness and offer protection from evil. Their priests wore lapis beads in prayer, an example of early symbolic associations of the stone with the heavens. For these ancient people, this vivid blue, hewn from the earth, presented a connection with the divine. Although lapis was to continue to be revered in religious art and culture, it started to shine during the rise of Ancient Egypt.

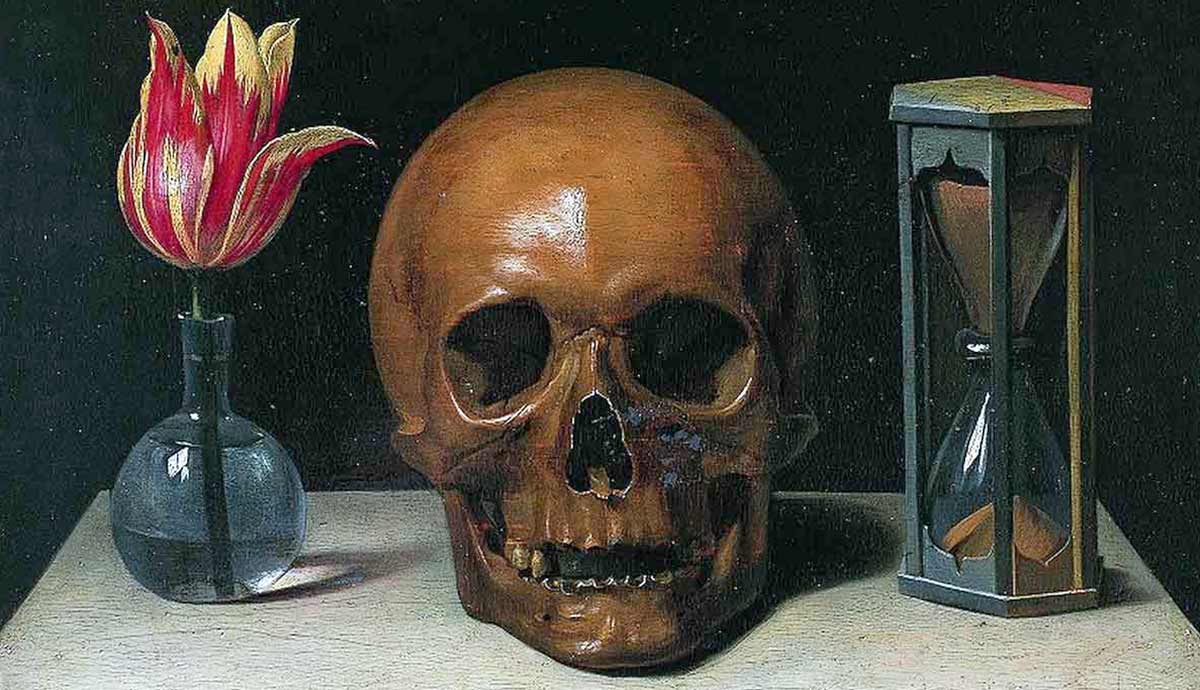

Old Blue Eyes, Staring Out From Beyond the Grave

Once the trade in lapis lazuli reached Ancient Egypt, it meteorically rose to the most highly prized and costly stone with which to make your mark in life, and death. The talismanic gold and blue of the funerary mask of Tutankhamun is etched into all our minds, but carvings of other gods were common offerings. Lapis lazuli became the emblem of a prosperous afterlife with grave goods carved from it and adorned with gold filling the tombs of the Pharaohs. Beyond the reach of mere mortals, to Ancient Egyptian royalty, lapis lazuli symbolized heaven, the gods, and divinity. The Pharaohs were believed to be intermediaries between the gods and humanity, ensuring prosperity and correct observance of religious ceremonies.

Lavish burial chambers and the elaborate sarcophagi of Pharaohs spring to mind when we think of the sacred blue and gold associated with Ancient Egyptians, however, lapis lazuli had another much different use in Egyptian culture as a cosmetic. Ground and mixed with animal fats, lapis reputedly lined the eyes of Cleopatra, replicating the divine appearance of the goddess, Isis.

The Blue of Byzantium

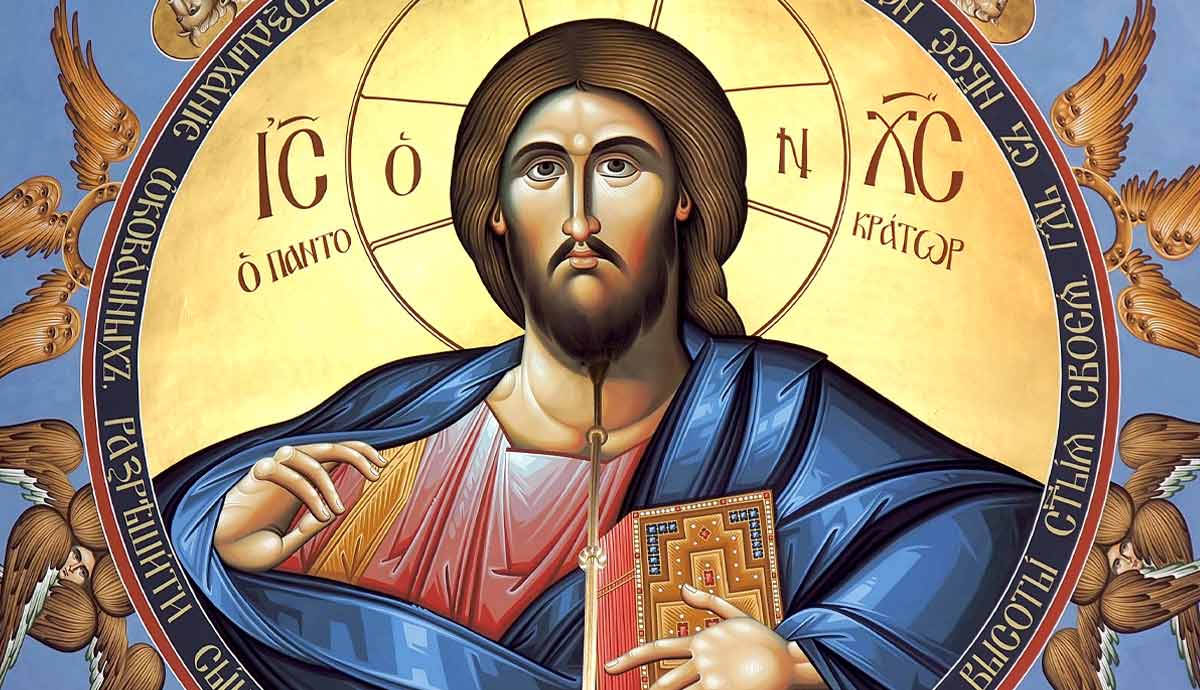

As trade in spices, gemstones, and gold extended from the Far East via Eastern Europe and beyond throughout the centuries, so lapis lazuli’s reputation grew. Symbolizing protection from evil and ensuring a prosperous afterlife for those who could afford to pay for it, lapis became the most sought-after commodity, worth more than gold in countries and empires around the globe. The Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire as it is also known, had grown wealthy and powerful by the 5th century CE. Its rich imperial and religious heritage gave us eminent structures such as the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (modern Istanbul).

Byzantine religious art, fueled by the riches and status of the church, was lavish in its use of precious stones and gold in the decoration of its sacred spaces. Icons of Christ and the saints covered the walls of churches, reinforcing the alliance developed throughout antiquity between lapis lazuli and the divine.

Blue Planet: Lapis Lazuli Around the World

While the cultural and religious art of Ancient Egypt and Byzantium feels familiar through its dissemination via the media and art historical books, further afield this cherished stone held other civilizations in its grasp. In China, lapis lazuli is revered for its healing properties and enhancement of a positive outlook. Its spiritual aspect is not neglected. Known as the “blue-gold stone of heaven” following its arrival in China via the Silk Road, lapis lazuli symbolized heavenly power. Imperial leaders used it in much the same way as the Ancient Egyptians, in ceremonies and rituals where they acted as emissaries of the gods.

Synonymous with the god Shiva in India, its use in Ayurvedic medicine reflected common global associations with healing and well-being. Lapis lazuli, known as “Yaqut” in Islamic tradition, is believed to represent the divine and truth. It is also referred to in descriptions of Jannah (Paradise) concerning the construction of palaces and mosques as a protective element.

The Cult of the Virgin: Marian Blue Emerges

Lapis lazuli was known worldwide by the 13th century and was revered for its believed healing and protective properties. In Europe, used as the pigment ultramarine, Christianity wholeheartedly adopted it. The growing cult of the Virgin Mary had gained momentum in the early Middle Ages in the form of the icon of Theotokos or Mother of God. In 431, the Council of Ephesus decreed that Marian veneration was official dogma and the creation of icons of the Virgin was approved.

As the centuries progressed, churches devoted to the Virgin were built throughout the continent and, in later years of the period, were financed by wealthy trading or banking families such as the Medici and the Bardi in Florence. In addition to the spiritual properties of lapis lazuli, its rarity and consequent costliness were the major reasons for its widespread use. Patrons who wanted to impress their contemporaries, whilst advertising their pious veneration of the mother of Christ, commissioned paintings and even whole chapels dedicated to the Virgin. Using ultramarine for her robes in tandem with gold ensured everyone knew how wealthy they were and how devoted to their Christian faith they claimed to be.

In the 14th century, Giotto di Bondone was commissioned by Paduan money-lender Enrico degli Scrovegni to paint devotional images on the walls and ceiling of the Arena Chapel, which Scrovegni had built. It is on the ceiling of the chapel, devoted to Saint Mary of the Charity, that one of the most impressive and extensive uses of ultramarine in art history can be found. It was rumored that Scrovegni ordered the use of such expensive materials in his chapel to atone for his sins as a famed money lender. Certainly, the chapel ceiling, covered in heavenly blue and littered with gold stars, and showing the Virgin robed in ultramarine speaks of great wealth and piety.

Ultramarine in the Renaissance and Beyond

With Giotto’s Scrovegni Chapel, it may have seemed as though ultramarine could not be used any more extensively in art and culture. However, as the Medieval period gave way to the Renaissance, this sacred pigment’s star rose higher. In Florence, the Medici, the preeminent banking family of the period, sought to cement their reputation as patrons of the arts and good Christians, with infinite commissions. Although the work they invested in maintained a religious premise, methods such as pietra dura, the use of soft and hard stones in the creation of decorative pieces, saw lapis lazuli move away from the divine.

Fernando di Medici, in the early 17th century, ordered the making of a table depicting the port of Livorno in pietra dura. The tabletop portrays the strategically important port holding captured Turkish ships with the Melora lighthouse also depicted. There is even an image of the tower in Pisa. Intended to impress upon visitors to the Uffizi, where it may have been initially displayed, it is a powerful image of the wealth and political power of the Medici. In true Medici style, the sea is fashioned from thin slices of lapis lazuli. The effect of the vibrant blue is striking, and its message of wealth would not have been lost upon the viewing public.

Vermeer and the Cost of Color

Ultramarine’s hold over the art world and high society did not weaken as the 17th century arrived. The religious paintings and Marian culture still held sway, but secular art was becoming more common. Johannes Vermeer, working in the Dutch city of Delft, produced relatively few paintings during his career and kept to a limited palette. He is known for his extensive use of ultramarine; a habit some have attributed to the ability of wealthy patrons to finance its use and a practice that is said to have left his family destitute after his death.

Examples such as his Young Woman with a Water Pitcher, executed in 1662, show how Vermeer did not reserve his use of ultramarine for swathes of color but employed it to emphasize highlights or to reflect the sky. Ultramarine in his paintings elevates the everyday subject matter of middle-class family homes and their inhabitants. His work diverts somewhat from the Renaissance glitz of ultramarine and gold used in excess and offers the viewer a subtle and intimate peek into the subject’s life.

The Real Thing? Lapis Lazuli, or Maybe Not

Following the excesses of the Renaissance and Vermeer’s lavish use of ultramarine, the pigment, so expensive to produce, began to fall from favor in the 18th century. Chemists developed synthetic blue pigments and dyes that were employed in painting, fabric dyeing, and decorating porcelain, to name a few uses. Ultramarine reverted to being the rarified luxury that it had once been. Cobalt and Prussian blues emerged and, in the art world by the 19th century, the Impressionists had replaced ultramarine in their paintings. Renoir used Cobalt blue extensively, as did Monet and Van Gogh.

20th Century Blue: Yves Klein and IKB

Lapis lazuli had largely lost its place in society and culture by the advent of the 20th century. No longer seen as a sign of wealth and power, nor popular in religious iconography, it became a mere semi-precious gemstone occasionally used in jewelry. In art, synthetic pigments were further developed with natural ultramarine’s nemesis finally appearing in the early 1960s courtesy of French artist Yves Klein and chemist Edouard Adam. International Klein Blue, or IKB, was a pure, flat ultramarine containing none of the shimmering elements of the original lapis lazuli pigment. It suited the modernity of the Sixties and when used in Klein’s signature blue rectangle paintings. IKB seemed to be the final nail in the coffin of its prestigious ancestor.

Lapis Lazuli: The Journey Continues…

While the use of lapis lazuli as a status symbol in art and architecture may have diminished over recent centuries, its position in the sphere of healing and spirituality continues. Primarily used in jewelry, lapis lazuli in the 21st century is more likely to adorn those seeking to worship the cult of ‘wellness’ where it is associated with communication and serenity than to guarantee safe passage into the afterlife as the Ancient Egyptians believed.