Not only does the New Testament present Jesus as having refrained from using violence, he also reportedly taught his followers to love their enemies and to respond to evil with good. While Jesus taught that God would one day judge the wicked, he never suggests that humans should attempt to participate in this judgement. These prominent characteristics of Jesus’s life and teachings has have implied for many throughout Christianity’s history that followers of Jesus should refrain from using violence.

Pacifism, not “Passive-ism”?

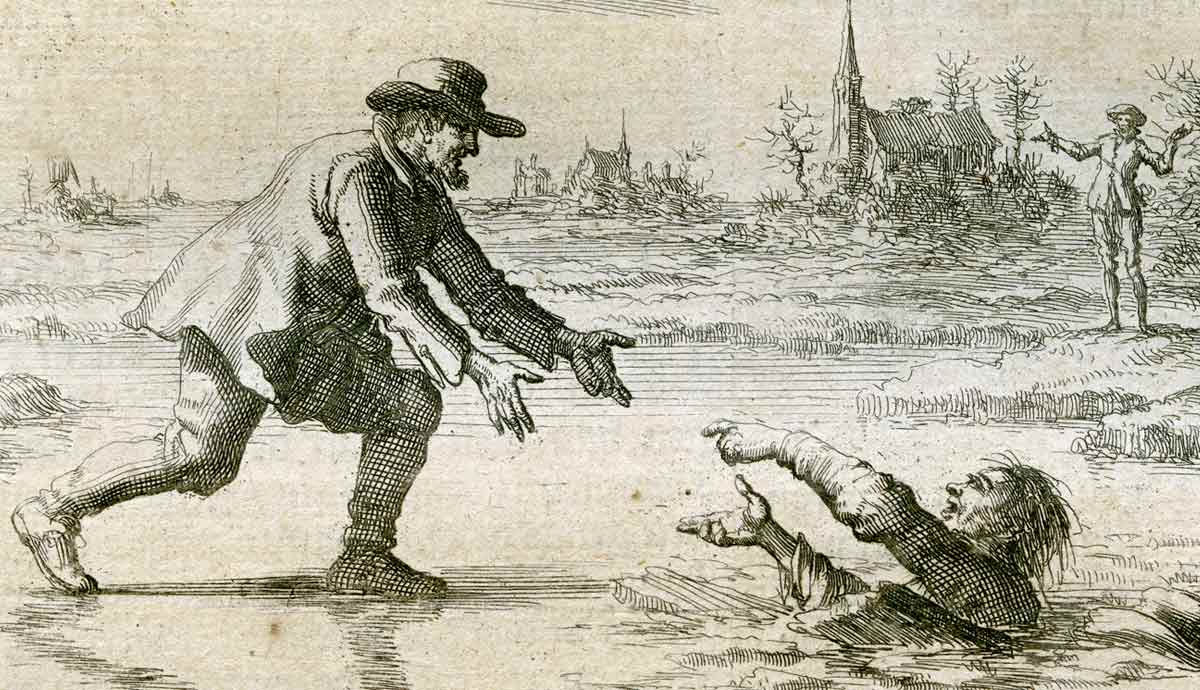

The root of the word “pacifism” is the Latin pax, meaning “peace.” To be “pacific” means to engage in peacemaking. Fundamentally, the word suggests an active pursuit; it does not connote passivity. Still, Christian pacifism has struggled to evade accusations of encouraging inaction. Christianity’s central image, after all, is a man nailed to a cross—executed against his will. On its face, such an image evokes surrender or capitulation to evil rather than active opposition.

However, according to Christian theology, the cross is a paradoxical symbol of battle. From a Christian point of view, Jesus was intentionally confronting and exposing the weakness of evil through his own execution, knowing that he would be vindicated when God would raise him from the dead. Thus, while pacifism is not unique to Christianity, Christian pacifism sees itself both as a philosophy based on the teachings of Jesus and as a logical corollary of the belief that death is not ultimate.

What Is the New Testament’s Stance on Violence?

The Hebrew Bible, known to Christians as the “Old Testament,” contains a great deal of violence, much of which is either sanctioned or directly committed by God. However, Jesus’s life and teachings, as they are represented in the New Testament, suggest a break from this precedent. The closest that Jesus comes personally to committing an act of violence in the Gospels is when he drives the moneychangers from the Temple with a whip—which the text says he fashioned himself. But even this passage may fall short of depicting a violent Christ, for the wording could be interpreted as his having used the whip to drive out the sacrificial animals only, not the moneychangers themselves.

Overall, the New Testament envisions Jesus as a man committed to nonviolent means of accomplishing his aims. Jesus famously—and possibly uniquely—taught his followers to love their enemies and to return good for evil.

Was the Early Church Pacifist?

For most of the church’s history, pacifism has been embraced by a small minority of Christians. But during the first three centuries after Jesus Christian theologians largely assumed that following Christ meant forsaking violence. Historians disagree about how thoroughgoing the early church’s commitment to peace was, with some noting that Christian soldiers were not required to relinquish their occupation. Still, the reason there is legitimate debate about the matter is because there are no clear examples in the early church of Christians enjoining violence as a proper response to their enemies.

This historical ambiguity takes a decisive shift, however, after the Roman emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in the Edict of Milan. As an illegal, minority faith, the probability that Christians would have been able to successfully employ the sword to defend or advance their interests was low. But as a legitimate religion destined, eventually, to be favored in the Roman Empire, the sword proved an attractive tool.

A Minority—But Persistent—Philosophy

After Christianity’s legalization in the Roman Empire, the church began to require pacifism only of clergy. However, the Reformation later challenged the clergy-laity separation itself. A movement that arose from within the Reformation in Central Europe was started by clergy who felt that the prominent Reformers had not gone far enough to return to the teachings of the New Testament. Called “anabaptists” pejoratively, members of this movement eventually came under the fierce persecution both of the Reformers and the Roman Catholic Church alike.

Of the several factions within this movement, only those who held to pacifism as a key tenant survived the Reformation era. These Anabaptist groups (including the Church of the Brethren, the Amish and Mennonites), along with the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), are known today as the “Historic Peace Churches.” Other, more recently-formed movements such as the Seventh-Day Adventist Church and the Jehovah’s Witnesses have also adopted pacifism as an official creed.

Pacifism and Modern Warfare

Since the fourth century, the only Christian, morally sophisticated alternative to pacifism has been “Just War Theory,” a carefully-formulated set of rules for how a morally justifiable war should be fought. One of these rules is that noncombatants are never to be targeted. The conversation around violence within the church has taken on new dimensions as new technologies have exponentially increased the destructive capabilities of modern weapons, making the possibility of a war in which civilians are not targeted increasingly elusive. Some who might have been persuaded by the arguments of Just War Theory in the past find themselves approaching a practically pacifistic stance in the face of modern warfare technologies.

At the same time, many members of Historic Peace Churches in the USA and Canada decided join the armed forces in World War II. Thus, the divide between the “peace churches” and other churches is not as stark as it once was.

What Was the Nonviolence of Martin Luther King Jr.?

Martin Luther King Jr. believed that evil was most effectively opposed by nonviolent means. This conviction informed the methods that he adopted as a leader in the Civil Rights Movement as well as his opposition to the Vietnam War. While King is known first and foremost for being a practitioner of nonviolence, he was also one of the most sophisticated theologians—or theorists—of nonviolence that Christianity has ever produced.

Despite his uncompromising opposition to violence, however, King’s theology does not fit readily into the classical Christian pacifism of the Historic Peace Churches. This is due, at least in part, to King’s unique political context. King addressed an audience of mixed religious convictions and, unlike the Anabaptists and Quakers, the oppression that he sought to address was based on racial rather than religious categories. In addition, his chief inspiration—apart from Jesus himself—was a the outspokenly non-Christian practitioner of nonviolence Mahatma Gandhi.

Was Martin Luther King Jr. a Pacifist?

King hesitated to speak of all violence in categorical terms—as if all violence was on equal moral footing. For King, violence employed in defense of the oppressed is not the same as violence committed by the oppressor. Rather than juxtapose violence per se with nonviolence per se, King held a nuanced view of violence as an inherently inferior, inevitably temporal, and morally corrosive tool for fighting oppression.

By contrast, love—which both requires and motivates nonviolent activism—is ultimately superior both in practical and ideal terms. In the short-term, this might not be evident. But in the long term, especially given his faith in the non-finality of death, nonviolence was the more promising response to evil in King’s view.