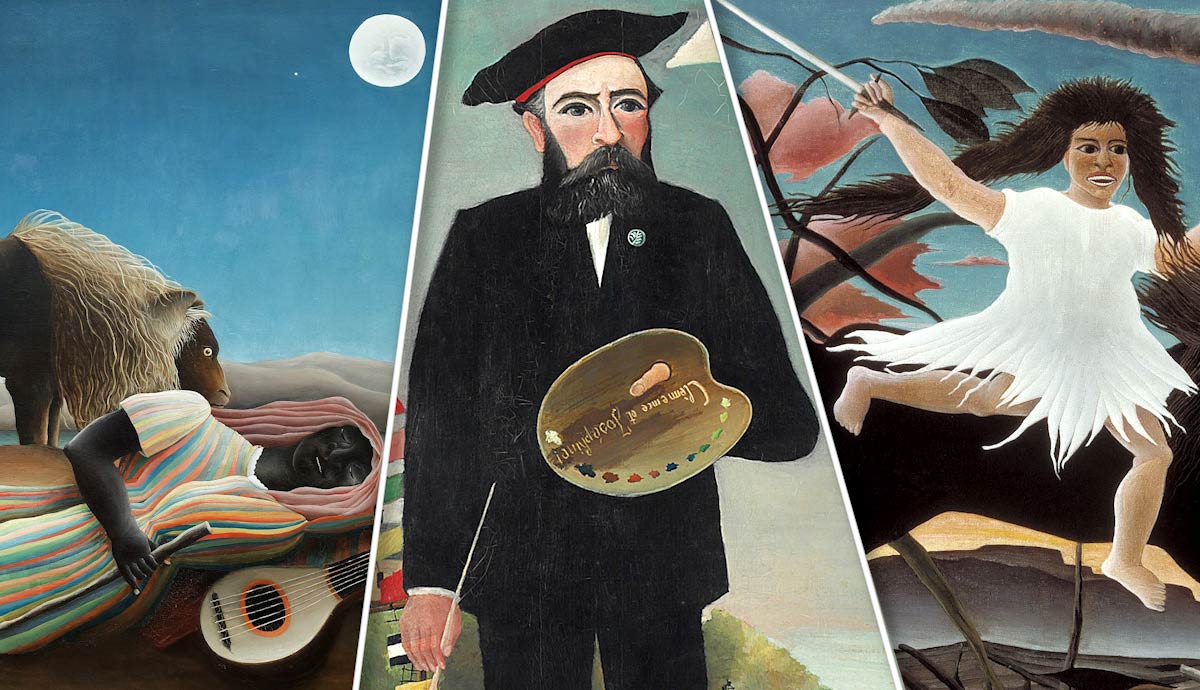

The French artist Henri Rousseau spent most of his life working as a customs officer before embarking on an extraordinary art career in his forties. Despite his lack of formal training, his unique vision captivated and profoundly influenced the most progressive young artists of his time. This article examines eight of Rousseau’s most significant works, each of which remains a source of fascination for art lovers worldwide.

1. Myself. Portrait-Landscape by Henri Rousseau

The famous Henri Rousseau was born in 1844 to a low-income family. Rousseau was painfully average in everything, barely demonstrating any particular talent or inclination. He enjoyed painting, but he couldn’t afford to make it his full-time career. He spent most of his adult life working as a customs officer until he quit his job in 1893 in order to focus on painting. The 1890 self-portrait illustrated the artist’s transition from a conventional lifestyle to a bohemian one. We can see the port the artist was working at before right behind his back.

The public image of Rousseau as a naive and innocent simpleton, which stuck around the art world, was largely cultivated by the artist himself. It was then picked up by art historians looking for a charming hero. On many occasions, Rousseau demonstrated an intent for deception or trickery, sometimes on a criminal level. He was briefly imprisoned in his early twenties for stealing from his employer. Years later, he was accused of money laundering, but he dodged the charges by acting like a confused old man framed by his younger peers.

2. Carnival Evening

The trend of naive art, produced by untrained hands that weren’t spoiled by either excessive self-consciousness or formal education, was picking up speed in the 1890s, and Rousseau was ready to embrace it. During the years of Rousseau’s artistic activity, being an avant-garde artist seemed respectable and fashionable. Yet he wanted more than to simply impress a group of young radicals. Having lived through a war and the bloodshed of the Paris Commune, Rousseau wanted to ensure stability and protection. His principal ambition was to gain recognition from the French State, thereby legitimizing his status as a great master.

However, Rousseau’s style of choice made it significantly difficult for him to win over the public’s affection. One of the earliest works exhibited publicly was Carnival Evening, which caused some critics to either laugh or cry right in front of it. Yet, for those who knew where to look, the piece offered much more. The detailed background was painted with precision atypical for a naive craftsman, revealing artistic intent and conceptual approach.

3. The Sleeping Gypsy

Rousseau had a special relationship with nature. He claimed that, as a penniless and lonely man, he had a sense of belonging while contacting the natural realm. Rousseau was married twice and had children, yet all of his family members had passed away before him. Despite the fantastic setting of his jungle works, many plants seen in these pieces are recognizable as particular species. Rousseau might have occasionally ignored proportion, but he never overlooked color—some of his paintings included up to 50 different shades of green.

Unlike the Impressionists, who sought to capture a fleeting feeling of a landscape, often sacrificing the real configurations of elements, Rousseau emphasized the objects and structures present in the scene. Despite the lack of hyperrealism, Rousseau painstakingly recreated buildings and details one by one, often striving to maintain consistent scale. In his imaginary scenes, he acted with more freedom, simplifying line and form in favor of pure expression and visual pleasure. One of the most famous paintings by Rousseau, titled “The Sleeping Gypsy,” was painted in a distinctly childlike manner, yet it conveys a comforting, magical feeling of an exotic dream.

4. The Dream

Despite his frequent portrayal of exotic plants and wild animals in the jungle, Rousseau never had the chance to see them in person in their natural habitat. He never left France, so he composed his dreamy environments inspired by everything he could find in Parisian botanical gardens and zoos. Thus, Rousseau’s tropical paradise was not an accurate depiction of a faraway land but a foreigner’s fantasy. His brand of exoticism was vastly different from that of Paul Gauguin or Henri Matisse, primarily because Rousseau did not present his works as objective reality.

Rousseau’s eclectic aesthetic and insertion of unexpected elements served as inspiration for the upcoming Surrealist movement. For example, The Dream features a Victorian sofa in the middle of a jungle. The Surrealists saw Rousseau’s jungle as the expression of the human psyche, with figures of women and animals representing hidden sexual and violent urges.

5. The Muse Inspiring The Poet

Sometimes Rousseau painted portraits of his friends and acquaintances, retaining his puzzling artistic persona. One of his most famous works was a portrait of Guillaume Apollinaire, an influential poet of his time and a leading theorist of Cubism. Apollinaire described how Rousseau took exact measurements of the poet’s head and body and even held paint tubes next to his face to find the right tone.

The level of meticulous attention to detail was absurd, yet for Rousseau, it was a necessary element of the painting process. That did not mean, however, that the final result would be realistic. The woman seen standing next to Apollinaire is the artist Marie Laurencin, often referred to as the poet’s muse. She was infuriated with Rousseau’s portrait, seeing herself portrayed as at least twice as big as she actually was.

Rousseau’s simple style, which was similar to folk painting, was often compared to the works of the Georgian self-taught prodigy Niko Pirosmani. However, given Pirosmani’s limited exposure to the history of art and artistic circles, most experts believe that Rousseau’s style was artificially created rather than developed involuntarily.

6. War (Discord’s Ride)

Violence is not typically a topic of discussion concerning Henri Rousseau’s oeuvre, yet his mythical works did not shy away from it. As a young man accused of theft, he chose to serve his sentence in the military instead of going to prison. Several years later, he was drafted again as the 1870 war with Prussia began. Personally, Rousseau never took part in military action, although he would later draw inspiration from stories in his friends’ military biographies. For years, he claimed to have served in Mexico and survived many battles and challenges presented by both humans and nature. However, we know that he never actually crossed the French border.

Nonetheless, Rousseau witnessed his share of gore and blood as he lived through the events of the Paris Commune in 1871. His painting War, perhaps the most intense and gruesome of all his works, certainly bore traces of this traumatic experience. This was also the first work of Rousseau that managed to convince the critics of the artist’s dramatic potential. Behind the piles of lifeless bodies, a trained viewer could notice the influence of Theodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, a gory illustration of the 1816 tragedy. Unusual was the image of a young girl in a fringed white dress, grinning from the back of a startled black horse like an unlikely Horseman of the Apocalypse.

7. Portrait of a Woman

The story of Pablo Picasso’s fascination with Henri Rousseau started in a surprising way. Rummaging through antique shops, Picasso found a box of unwanted canvases that were being sold to practicing artists for them to repaint. One of the paintings was Rousseau’s Portrait of a Woman, which Picasso bought for five francs. He went to great lengths to find the artist behind it. Contrary to rumors of Rousseau’s insanity, Picasso claimed that the customs officer’s work was an example of the clearest and most direct artistic logic—a carefully balanced and calculated man. Rousseau replied in his signature nonsensical manner, stating that Picasso and he were the greatest artists in history, yet Picasso worked in an Egyptian manner, while Rousseau was the only true modernist.

In 1908, Picasso even organized a banquet in honor of Rousseau and crowned him the king of painters. The event, however, was as chaotic as you might expect from a group of radical avant-garde artists. The room full of guests, including Apollinaire, Georges Braque, and Gertrude Stein, spent several hours waiting for the food from a local restaurant to arrive before they realized someone had confused the dates and ordered it for the following day. Unwilling to postpone the feast, the group made a makeshift dinner of homemade wine and canned sardines.

8. The Snake Charmer by Henri Rousseau

The Snake Charmer, painted in 1907, i a monumental work commissioned by the art dealer Berthe Weill. It stands as a prime example of Rousseau’s unique vision of the exotic. Under a luminous crescent moon, a dark-skinned and bright-eyed figure, typically identified as female, plays the flute. Serpents emerge from the shadows, their forms curving amidst the dense leaves. A host of exotic birds watch from the branches, their feathers rendered in meticulous detail.

Rousseau created this fantastical landscape based on his studies of botanical gardens. This allowed him to blend a diverse range of plant species into a seamless, dreamlike whole, despite never observing them in their natural habitat. But The Snake Charmer doesn’t necessarily aim for photographic reality. Rather, its simplified lines, flattened perspective, and rich colors create a dreamlike realm. Like all his work, this piece stands as a powerful testament to Henri Rousseau’s unique genius and his ability to transport viewers to a world beyond the ordinary.