Why did human cultures develop systems of writing? Was it for purely pragmatic reasons, to keep track of things like taxes and sales? On the contrary, in many cases, writing systems were developed to record religious beliefs and practices, and then found applications in more mundane areas. The link between religion and writing meant that in many cultures, writing was considered sacred and even had magical powers. Discover four early writing systems that were more than a tool for recoding the world, but a sacred text with supernatural applications.

Cuneiform

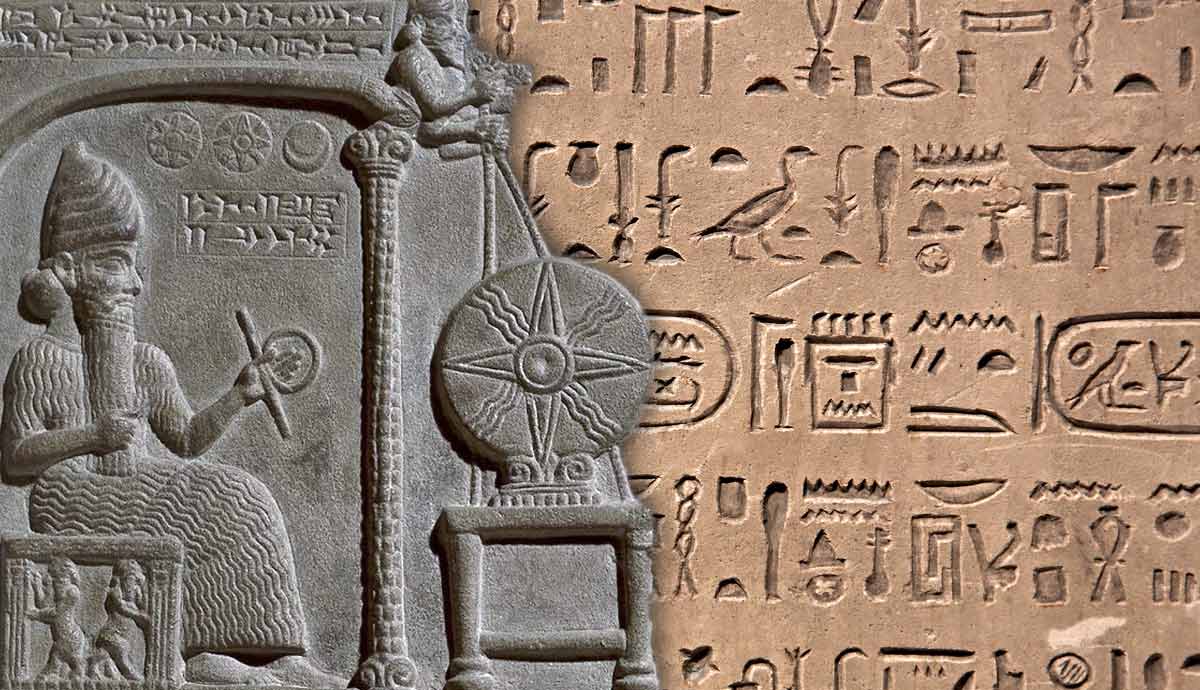

Cuneiform developed around 3,500 BCE in Sumer in southern Mesopotamia and may have been used until the 3rd century CE. The script was utilized by multiple civilizations and was compatible with a variety of languages. There are copious examples of surviving legal, historical, and commercial documents as well as royal proclamations, stories, mythologies, literature, hymns to the gods, spells, and astrological texts.

In ancient times, these themes were not seen as separate. Many royal inscriptions were dedicated to the gods, such as Sargon II’s Letter to Ashur, which described his military campaign against Uratu. In this, the king routinely praises the Assyrian pantheon and dedicates his successes to them.

The cuneiform script went through many phases and styles due to its diverse usage. Under the Sumerians, it was notably pictographic, and the symbols shared overt connections to the word they were portraying; for example, the sign for a ruler was a man with a headdress. The Babylonians and Assyrians adapted the pictograms into a more complex script and created texts that now had to be read by specialists. In these later variations, the signs could represent syllables or letters which could be joined to make words independent of their original denotations. Those trained to read and write cuneiform were mainly scribes or priests, who to the mainly illiterate populations must have seemed mysterious.

The spoken name of a magical or religious entity had long been equated to the conjuring of that being. Thus, the invention of cuneiform swiftly inspired the notion of written prayers to the gods as well as curses and spells that appeared on objects from bowls to amulets. Written curses have been found in multiple graves, including a famous curse inscribed on the walls of the tomb of Queen Yaba, wife of King Tiglath-Pileser III, which stated anyone who desecrated it would receive no offerings in the afterlife and remain “restless for all eternity.”

Hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphic script is thought to have developed independently from the Sumerian cuneiform around the same time in the 4th millennium BCE. Over time, the logograms progressed into greater abstract characters that no longer looked like the object or idea they represented. These scripts, called Hieratic and Demotic, were, however, more easily transcribed.

The original decorative hieroglyphs were still used under ceremonial or cultic circumstances far later than they were used for legal documentation or other practical uses. Whilst Egypt may have lost some political influence towards the end of the New Kingdom due to a host of new competitive empires, namely the Assyrians, it maintained significant cultic and cultural influence.

The ancient Egyptians believed that words themselves and associated images were instilled with transcendent powers. Within tombs and graves, we see protective texts and spells, often inscribed across tomb walls as well as on hieroglyphic amulets. Amulets or talismans were often used by the living but were also commonly found amongst the dead. A hieroglyph could symbolize something more than the word it was conveying. For example, the Djed pillar encompassed strength and steadiness, and the Wadjet or Wedjat eye, generally known as the eye of Horus, represented protection and rebirth.

The importance of a person’s written name is also evident from Egyptian tombs. An individual’s name was always displayed throughout their tomb: on the walls, sarcophagus, and even funerary goods within the tomb. Similarly, iconoclasm, especially pharaonic iconoclasm, or the act of destruction and erasure of a pharaoh and their beliefs, can be found predominantly in the demolition of their written names. Tutankhamun’s name, as well as the names of his parents, Akhenaten and Nefertiti, were chiseled out of inscriptions and king lists. While this may seem practical in the erasure of a person, statues and images were similarly defaced, with emphasis placed on damage to the nose and mouth to symbolically prevent the victim from breathing.

Greek Alphabet and Numerals

The Greeks adopted the Phoenician alphabet, which consisted of 22 symbols. The simplicity of the script made it much easier to memorize and, therefore, more accessible to the wider population. The Greeks believed in an intrinsic magical association with written scripts and came up with numerology, the belief in divination by numbers. The difference between written numbers and letters did not emerge until the 8th and 9th centuries CE, so Greek numerals used the Greek alphabet.

Isopsephy is a practice that has been around since at least the 3rd century BCE and consisted of totaling up the numerical value of a word. If two (or more) words possessed the same numerical value, they were said to have some sort of higher connection. This was not unique to the Greeks, as the Hebrew tradition of Gematria was identical, and even the Neo-Assyrians demonstrated this belief. Pythagoras, the famed mathematician, conceived a theory in which a person’s name and date of birth could reveal one’s characteristics and future. This was done by taking numbers from each. Onyomancy, or divination based on the subject’s name, gained immense popularity in medieval Europe, and similar practices continue around the globe today.

The spiritual significance of the Greek language persisted as a key language of Christianity. The New Testament was originally written in a form of Koine Greek. It was these Greek texts that were translated into Latin for use by the Catholic Church and into other vernaculars for other denominations over time, especially after the Protestant Reformation. Meanwhile, the original Greek versions are still used by Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians.

Maya Glyphs

Originating around 2000 BCE as hunter-gatherers, the Maya reached their zenith from 600-900 CE but survived until the Spanish conquests in the 16th and 17th centuries. During their long-standing civilization, the Maya produced some of the most incredible ancient texts using a unique glyph-based writing system. The script is formed using logograms and syllabic or spoken signs. To begin with, this script was called Maya hieroglyphs due to its similarity with Egyptian hieroglyphs observed by 17th and 18th-century European travelers, although there is no connection between the two scripts. The glyphs are complex and artistic, with both writers and artists being labeled t’zib.

The famous Maya Haab’ solar calendar is considered among the most accurate from the ancient world. Time was measured and recorded intensely for two main reasons. The first is that the Maya viewed time as cyclical, meaning that both in the short and long term, history would repeat itself. The second reason was due to an intricate system of religious events which manifested in their 260-day Tzolkʼin calendar. Bloodletting was an important ritualistic form of sacrifice in the Maya religious calendar. Royal family members were expected to participate in the practice on specific dates dictated by the calendar. The tools that were used to draw blood in these rituals were heavily decorated with glyphs.

Maya beliefs were reflected in Maya writing. For example, the Maya believed in a watery underworld. In some caves associated with the underworld, dates are inscribed on the walls that do not make sense. This is because time and space in the underworld were viewed as warped and incomprehensible to humans. The underworld, as with the upper world, was a supernatural realm and did not adhere to the same conventions as the human domain (or middle world).

Sadly, most of the Maya written works were destroyed by the invading Spanish, but three codices survive to this day. Interestingly, all three texts focus on ritualistic timekeeping, deities, and other celestial entities and practices. Astronomical information and ornate illustrations of deities feature heavily in the Dresden Codex, whilst the Madrid Codex details sacrifices, divinations, and accounts of warfare. Despite its fragmentary nature, the Paris Codex also describes rituals and Maya celebrations. Imagery of gods is frequent, not just in these codices, but in all Maya artwork. Similarly, these motifs are typically paired with glyph captions, describing the actions of these deities.

Other Sacred Scripts

The belief that scripts were sacred seems to have diminished with the spread of literacy. For example, while the Romans seem to have had reverence for their script early in their history, as it was increasingly used for administrative and other purposes, that connection broke down. This more pragmatic approach to writing spread with the Roman Empire.

Nevertheless, we still see other sacred scripts in later times. For example, the Vikings considered their runic script, Futhark, to be sacred, given to them by the god Odin as both a way to describe the world and as a magical toolkit, leading to the development of rune magic. This partially explains why the Vikings relied more on oral histories than written texts and have left no written pose about themselves, using. They principally used their text for monumental inscriptions. When the Norsemen began to write their histories in the 12th century, they used a version of Latin adapted to write Old Norse.

Ogham was a script used in Celtic Ireland and Western Britain between the 4th and 6th centuries CE. Some scholars believe that it was used by the Druids specifically as a sacred script to protect their religious knowledge from the Romans. Irish tradition suggests that the script was invented over 4,000 years ago, shortly after the fall of the Tower of Babel, by the legendary Scythian King Fenius Farsa and a group of scholars when they were investigating the many “confused languages” that were sent out of Nimrod’s tower early in Biblical history. After ten years of study, they created Ogham. While these origins seem unlikely, they show a continued belief in a connection between written language and religion.

Chinese writing also had sacred origins, with the oldest examples, dating from the 2nd millennium BCE, being oracle bone inscriptions made to record the results of divinations conducted by the Shang royal family. The characters posing the question were inscribed on bone, and the bones were then heated on a fire, and the cracking was used to interpret an answer.

Collectively, we can see that many cultures develop their writing systems as an extension of their religious beliefs and practices, but this practical approach to recording and sharing information then found its way into every part of life.