Calypso was a beautiful nymph who lived alone on the isolated island of Ogygia. Her solitude changed when the shipwrecked hero Odysseus washed ashore. Calypso fell in love with him and offered him immortality and an idyllic paradise in exchange for staying with her and marrying her. However, Odysseus longed to return home to his wife, Penelope. Despite Odysseus’s pleas, Calypso kept him with her for seven years until the gods intervened. Discover the fascinating story of Calypso and what her tale reveals about love, freedom, and temptation.

Etymology of Calypso’s Name

The name Calypso can be roughly translated to mean “Concealer.” It comes from the ancient Greek word kalúptō (καλύπτω), which means “to cover,” “to conceal,” or “to hide.” This name highlights her essential role and relationship with Odysseus in the Odyssey. She hides him on her remote island for seven years, preventing him from returning to his family and drawing the gods’ attention.

Calypso’s Family

In the Odyssey, Homer states that Calypso is the daughter of the Titan Atlas, but he provides no information about her mother. Atlas played a significant role in the Titanomachy, the war between the Olympians and the Titans. After defeating the Titans, Zeus punished Atlas for his role in the war by condemning him to bear the weight of the sky for eternity. Some scholars believe that Calypso was exiled to the remote island of Ogygia, which many think may refer to the Maltese island of Gozo. This exile may have resulted from her siding with her father during the war or as a way to distance herself from the gods who imprisoned him.

In his poem Theogony, Hesiod presents an alternative genealogy for Calypso, stating that she was one of the Oceanids, a group of sea nymphs born from the Titans Oceanus and Tethys. Conversely, Apollodorus recorded that Calypso belonged to the Nereids, another group of sea nymphs, who were the offspring of the sea deities Nereus and Doris. Some scholars speculate that there may have been three distinct nymphs named Calypso that originated from similar sources.

Although Homer does not mention children, Hesiod asserts that Calypso had two sons with Odysseus, Nausithous and Nausinous. According to the Roman writer Hyginus, Calypso and Odysseus also had a son named Latinus. However, most traditions attribute Latinus to Odysseus and his other island lover, the sorceress Circe.

Abilities

There is limited information about Calypso outside of her appearance in the Odyssey. All sources agree that she was a nymph and a lesser deity, specifically a female nature spirit personifying various elements of the natural world. Although not explicitly stated in the Odyssey, she is likely a sea nymph, a notion supported by alternative genealogies provided by Hesiod and Apollodorus.

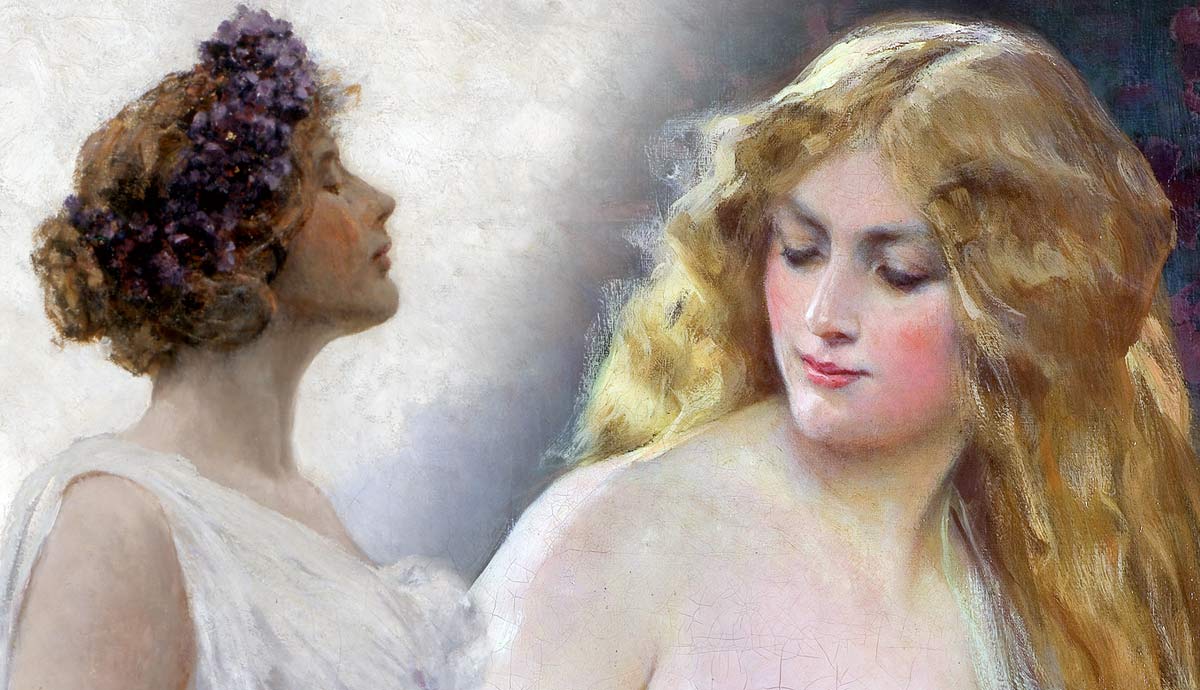

Calypso was not an ordinary nymph; Homer describes her as a goddess of strange and awesome power and beauty. Unlike most nymphs, Calypso was immortal and could grant immortality to others, which she attempted to do with Odysseus. While Homer does not provide further details about Calypso’s mysterious powers, she is depicted controlling the winds to ensure Odysseus departs safely from her island. Her home is described as a natural paradise, which she probably created with her influence over the natural world, a common trait among nymphs. Although the exact nature of Calypso’s power and influence is unclear, she was a powerful nymph-goddess existing in a transitional space between lesser deities such as nymphs and the immortal gods of Olympus.

The Myth of Calypso: Ending Solitude

In the Odyssey, Calypso’s story begins when the hero Odysseus washes up on her island. For over a decade, Odysseus faced numerous trials and tribulations while attempting to return home to his wife, Penelope, and their son, Telemachus, after the Trojan War. During his journey, he encountered the Cyclops Polyphemus, endured the Sirens’ songs, and survived the threats of the monsters Scylla and Charybdis. He also matched wits against the sorceress Circe, becoming her lover for over a year, and even descending into the Underworld.

Despite enduring so much, Zeus destroyed Odysseus’s ships and drowned his entire crew to appease the sun god Helios, after the crew slaughtered and ate some of Helios’s sacred cattle. Only Odysseus refused to eat any of the sacred cattle, so Zeus spared him. Odysseus survived nine days at sea on a makeshift raft that he constructed from the debris of his sinking ship. On the tenth day, just as he was ready to surrender to the sea, he washed ashore on Ogygia, the island of Calypso.

When Calypso discovered Odysseus exhausted, dehydrated, and alone on her shores, she took him to her home and nursed him back to health. It is unclear whether her motivations were rooted in pity, kindness, or simply loneliness from being isolated on her island. At first, Calypso served as Odysseus’s rescuer, helping him regain his physical and emotional strength after enduring rough seas and losing his entire crew. However, her feelings changed, and she fell deeply in love with him.

The Myth of Calypso: Lover and Captor

Initially, Odysseus reciprocated Calypso’s feelings and appeared content to provide her with the companionship and affection she desperately needed. One of Odysseus’s character flaws was the contradiction between his deep desire to return to his family and his continual acts of infidelity, which delayed his journey home. Earlier in his journey, he spent a year as the lover of the sorceress Circe and only chose to leave when his crew became restless and urged him to depart.

The duration of Odysseus and Calypso’s love affair remains unclear, but eventually, Odysseus’s heart and mind shifted back to his ultimate goal of returning home. When he expressed his desire to leave, Calypso refused to let him go; any thoughts of escaping from a goddess as powerful as she were futile. To convince Odysseus to remain with her, Calypso promised to make him her immortal husband. This divine offer would tempt anyone: an eternal youth shared with one of the most beautiful women in the known world, set on a paradise island. However, at every turn, Odysseus rejected Calypso, refusing to abandon his ultimate goal of returning home to his wife and son. This marked a significant shift in their relationship, as she transformed from being his rescuer and lover into his captor and jailer.

A Tempting Paradise or a Tormenting Prison?

Odysseus spent seven years trapped on Calypso’s island, sitting on the beach, gazing out at the sea toward his home with tears in his eyes. Despite the many comforts that Calypso’s island provided, he was consumed by homesickness. The mythical Ogygia was a paradise that offered many temptations, likely persuading most people to abandon their dreams of the outside world.

Calypso’s home, often called a cave, was a stunning example of natural beauty. Homer describes this ethereal palace with vivid detail, where towering alder, graceful aspen, and aromatic cypress trees arch over the entrances, creating a peaceful sanctuary for melodious birds that fill the air with their sweet songs. Trailing garden vines drape over the entryway. Surrounding the abode are lush violet meadows and fragrant wild parsley, forming an exquisite tapestry of colors and scents. Nearby, four crystal-clear spring fountains bubble cheerfully, sending water in all directions. Inside, fragrant cedar and juniper wood crackle in the hearth, filling the island air with a delightful aroma. Meanwhile, an immaculate garden bursts forth with plump, glistening grapes.

Despite all the luxuries Calypso offered, Odysseus refused to be coerced into staying with her. Even though Calypso had confined him to the island, limiting his freedoms and compelling him to spend each night with her, he still held one vital freedom: the power of choice. He could choose between mortality and immortality, selecting what he truly loved—his wife, son, and home in Ithaca—over Calypso and her island paradise. Perhaps the immortal goddess thought that if she waited long enough, Odysseus would eventually give up his final freedom over time, unable to resist the alluring temptations of her home. This may have happened if not for the intervention of the goddess Athena.

The Hypocritical Gods

Athena served as Odysseus’s patron deity throughout his journey home. Worried about Odysseus’s seven-year confinement by Calypso, she approached Zeus, the king of the gods, and asked him to intervene and order Calypso to free Odysseus and allow him to return to his destiny. Zeus agreed with Athena and instructed Hermes, the messenger of the gods, to travel to Ogygia and deliver a simple message to Calypso: release Odysseus.

When Hermes finally reached the remote island of Ogygia, he found Calypso in her home, singing a lovely song as she wove at her loom. While she sang happily, Odysseus wept on the beach, longing for home. This striking contrast emphasized the disconnect between the two inhabitants of the island. For Calypso, it was paradise; she was no longer alone and was living with the man she loved. In contrast, for Odysseus, it felt like a miserable prison, thinly disguised by luxurious furnishings. However, Hermes’ message from Zeus shattered the idyllic facade for Calypso. Zeus’s word was law; no entity, whether mortal or immortal, could defy the commands of the king of the gods without facing dire consequences. The Olympians likely thought Calypso would reluctantly agree to release Odysseus, but they did not anticipate her reaction.

Calypso was furious. She was not just another compliant follower of the Olympians; she was the daughter of the mighty Atlas, who had once fought against them. Calypso launched into a speech, outlining the hypocrisy of the male Olympian gods and the unfair double standards they imposed on goddesses in love. She called out these male gods as nothing but jealous men who could not bear to see their female counterparts engage in relationships with mortals.

Calypso recounted how Eos, the goddess of the dawn, fell in love with the mortal hunter Orion, only for Artemis to kill him. She also shared that when Zeus learned that Demeter had fallen in love with the mortal Iasion, he struck him down with one of his thunderbolts.

Calypso concluded her speech by addressing her relationship with Odysseus, reminding Hermes that it was Zeus who had sunk Odysseus’s ships and sent him to her island. She had nursed him and provided him with every pleasure during his stay. Despite her love for him, she is now forced to release him and return to her lonely solitude. Meanwhile, no male god ever truly faced consequences for loving a mortal. Indeed, Zeus famously abducted Prince Ganymede of Troy and made him his immortal cupbearer and lover, which parallels Calypso and Odysseus. Yet, no one ever punished or even questioned Zeus for his actions.

Despite her anger and criticisms of Olympus, Calypso reluctantly obeyed Zeus, as she could not defy his orders. Her protests, followed by her reluctant acceptance of his commands, highlight the restrictions on freedom she had previously mentioned that were imposed on female goddesses. After Hermes left, Calypso found Odysseus weeping on the beach, gazing longingly toward Ithaca. Overwhelmed by anger and sorrow, she revealed that he was now free to depart. By being forced to give up one of her freedoms—the freedom to keep her love—she granted Odysseus the freedom to leave her island and pursue his love.

The Myth of Calypso: Return to Solitude

At first, Odysseus does not believe Calypso when she tells him he is free to leave. After years of confinement, he has grown cynical and distrustful of her words. It is only when Calypso swears an oath on the River Styx, promising not only to let him go but also to ensure that no misfortunes occur during his departure, that Odysseus finally accepts her claim. The pair then retreats to Calypso’s home to share a meal, where Calypso tries for the last time to persuade Odysseus to stay with her.

Calypso informs Odysseus that his journey home is far from over and that he will encounter more trials and hardships before he finally returns to his home and family. She then questions why anyone would choose such difficulties over the comfort and luxury of her island. More importantly, she wonders why anyone would opt to be with an ageing mortal rather than an ageless and divinely beautiful goddess like herself.

As politely as he can, Odysseus cautions Calypso to be careful when speaking about his wife, Penelope. However, he agrees with her; he acknowledges that she is more beautiful than Penelope and that his rocky island home of Ithaca cannot compare to the paradise of Ogygia. Despite these truths, he yearns for Penelope and his home daily because they are what he truly loves and longs for. He notes that he has faced numerous trials and hardships on his journey, and if he must endure a few more to reach home, then so be it. Odysseus’s words silenced Calypso’s pleas, and as the sun set, they went to her bed for one last night together, staying by each other’s side until morning.

The next day, Calypso provided Odysseus with food, an axe, and an adze. She guided him to the other side of the island, where he found tall alder, aspen, and silver fir trees—ideal for building a ship. Odysseus spent four days constructing his vessel. He quickly cut down the trees and used the adze to trim and smooth the wood. During this time, Calypso left him to work alone but brought him an auger to aid in the construction and cloth for making a sail. On the fifth day, she bathed Odysseus and dressed him in fragrant clothing. She also provided him with provisions, including wine, water, and a sack filled with delicious food. Fully prepared and stocked, Calypso summoned a warm, favorable wind to help Odysseus begin his journey.

This marks the conclusion of Calypso’s story in the Odyssey. Homer does not provide any final words or farewells between Calypso and Odysseus. Perhaps after Odysseus’s last rejection and declaration of love for Penelope and his home, there was no need for further words. According to the Fabulae by Hyginus in the 2nd century CE, Calypso ends her life after Odysseus departs. However, other traditions suggest that once Odysseus’s raft vanished over the horizon, Calypso sat on the same beach where Odysseus had once sat, gazing with tears in her eyes towards Ithaca and her unrequited love.

The Nature of the Myth of Calypso

Calypso represents another challenge that Odysseus must overcome on his heroic journey. However, she is more than just an obstacle; her love for him is genuine but framed by a profound loneliness. Yet this love gradually becomes possessive, as she refuses to let go of her only companion despite his continual pleas to leave. Calypso’s possessive love and fear of isolation ultimately confine Odysseus, making her a jailor who traps him.

The temptations offered by Calypso would be difficult for anyone to resist. The combination of time, love, and memory makes it even harder for Odysseus. He has not seen his family or home for nearly 20 years. Throughout the Odyssey, he grapples with anxieties about whether his wife, Penelope, has moved on and remarried or if his son, Telemachus, even remembers him. These worries present a significant challenge: is it worth continuing his long and arduous journey, which has already taken so much from him? What if he returns home to a family that no longer loves or remembers him? All of these concerns compete with the temptations right in front of him.

The allure of eternal youth is one thing; Calypso’s beauty and paradise island are another. However, it is also undeniable that Calypso genuinely loves Odysseus. Despite these temptations and the certainty of luxury and divine love that she offers, Odysseus ultimately rejects Calypso in favor of something more beautiful: the experience of the fragile nature of human existence.

Mortality is finite, and while it can be tumultuous, it encompasses a range of positive and negative experiences. The limitations of our time make every second and each experience we create for ourselves and share with others meaningful and valuable. However, these precious moments lose their significance when faced with eternity.

Calypso’s isolation highlights the dangers of eternal youth. Is immortality and an island paradise worth it if you have no one to share them with? Calypso denounces the Olympians’ double standards and hypocrisy regarding the goddess’s love for mortals. She defies their beliefs and attempts to reject Zeus’s command to free Odysseus. However, ultimately, she is powerless against the demands of fate and destiny; her freedom to love who she desires is taken from her, condemning her to an eternal life of loneliness. In Calypso’s tragic existence alone in paradise, Homer alludes to the perils of choosing stagnant immortality over the dynamic, fragile, and turbulent experience of mortality.

The myth of Calypso is poignant. It illustrates the dangers of stagnant pleasures, the pain of loneliness, how genuine love can be both positive and painful, and the beauty of human existence.