We all have an idea of the Gothic from popular culture. The word conjures up images of deathly creatures and dark corners: ghosts lurking in haunted hallways, vampires sucking blood, mummies and zombies defying the grave. This long-standing literary genre is all about making our pulses race with terror. But if we sink our teeth into the classic works of Gothic literature, we might find that there is even more to the genre than chills and thrills.

1. Frankenstein, Mary Shelley

There were Gothic novels in English literature before Frankenstein. In fact, the genre was so well established that Jane Austen bitingly satirized it in her novel Northanger Abbey, written in the late 1790s. Austen’s heroine is such a devotee of Gothic novels that she expects the titular abbey to be a romantic ruin, sheltering a family torn apart by vice and racked by supernatural happenings.

These were the conventions used by authors such as Ann Radcliffe, Matthew Lewis (known as ‘Monk’ Lewis after his scandalous Gothic novel The Monk), and Horace Walpole. Walpole’s Castle of Otranto in 1764 was the first novel in English to feature a host of Gothic stereotypes—notably, a haunted castle in the Gothic architectural style, lending the literary genre its name.

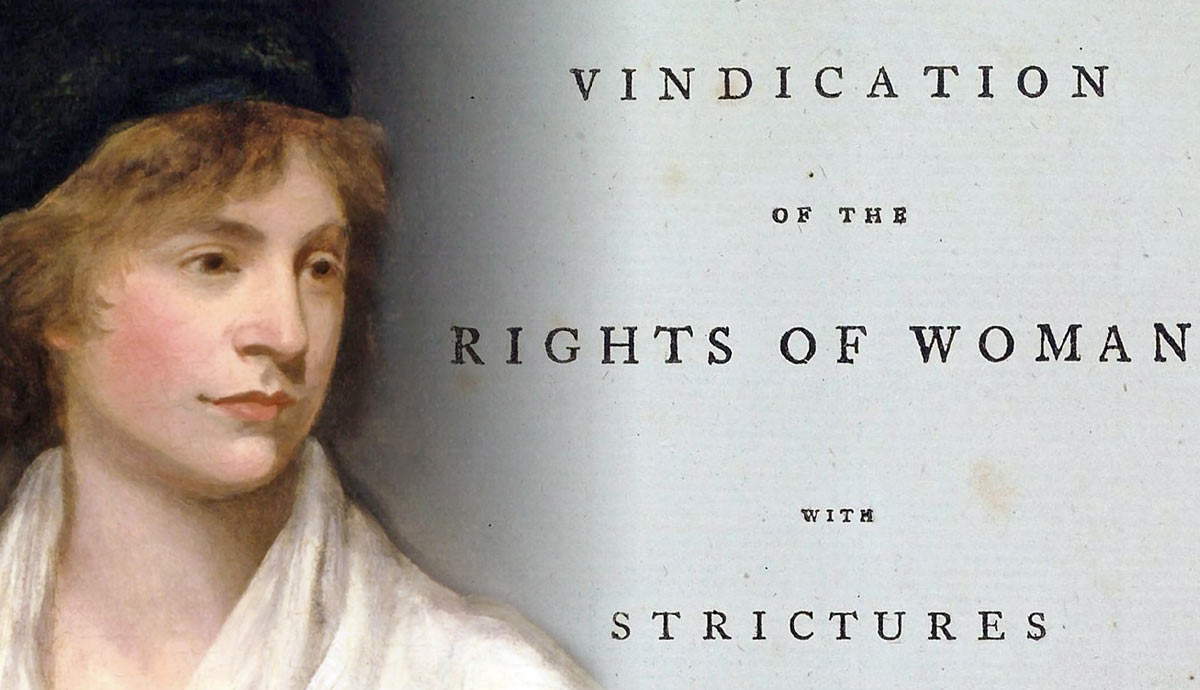

But Frankenstein was on another level. Mary Shelley, daughter of philosophers William Godwin and Mary Wollstonecraft, was just 18 when she came up with the idea for the novel, on one of the most famous nights in literary history.

In May 1816, Shelley and her husband, the poet Percy Shelley, traveled to the Villa Diodati on the shores of Lake Geneva to visit their friend Lord Byron. 1816 was known as the ‘Year Without A Summer‘ thanks to the lingering effects of volcanic activity in the Philippines the previous year. Taking refuge from the cold and rain, the poets gathered around the fire one June evening and challenged one another to a ghost story competition.

The result was Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s tale of one man’s attempt to play God by assembling body parts from corpses and bringing his creation to life through galvanism, or electric currents.

Unsurprisingly for the daughter of two philosophers, Shelley gave her novel a philosophical edge as well as amping up the horror. Frankenstein’s creature is no straightforward villain, but a figure of pathos whose isolation—starting with his creator’s horrified rejection of him—drives him to despair.

2. The Vampyre, John Polidori

Frankenstein is the most famous novel to emerge from the ghost story competition at the Villa Diodati, but it was not the only one. Accompanying Lord Byron at the time was his physician, John Polidori: like his companions, a Romantic with a taste for the supernatural and folk horror. Polidori’s contribution to the competition took up a figure from the latter category: the vampire.

Some 80 years before Bram Stoker’s Dracula immortalized the vampire as one of the defining images of the Gothic, Polidori’s story took the figure from among the many strange, part-human, part-monster creatures in folklore. Before Polidori wrote The Vampyre, the English reading public might only have come across vampires if they were particularly interested in Eastern Europe, where communities had long reported being terrorized by undead visitors who spread death wherever they went.

In Polidori’s hands, the vampire became the charming (and often nobly born) character we know today. His story tells of the protagonist’s corruption by the alluring, apparently indestructible Lord Ruthven. Conspicuously, the name Lord Ruthven had appeared in a novel published just a month previously: Glenarvon, by Lady Caroline Lamb. Although Lamb’s Ruthven is not a vampire, he resembles Polidori’s character in one crucial way. Both are modeled on Lord Byron.

Lamb, Byron’s former lover, and Polidori, his doctor, both wrote the poet into their novels as a man who was (as Lamb said) “mad, bad, and dangerous to know.” Especially dangerous in Polidori’s The Vampyre, as the Byronic character goes about seducing and slaughtering others.

This was no great concern for Byron. His own, aborted story at the Villa Diodati had also been about a vampire, and it was clearly an interest the two men shared. When The Vampyre was published in 1819, it came out under Byron’s name. Although this wrong was eventually righted, it was an apt turn of events for a tale that introduced the trope of the domination of impressionable young romantics by alluring aristocrats into the Gothic canon.

3. Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë

One hundred thirty years before it was a Kate Bush song, Wuthering Heights was a great Gothic novel. Like Frankenstein, it was the first (and in this case only) novel by its young female author, with vast, sublime landscapes for its setting and a tragic outcast for its protagonist. Like Frankenstein, Wuthering Heights explores how the haunted can come to haunt others.

Heathcliff is the most Gothic element of Wuthering Heights. Depending on your reading of the novel, he might be considered literally haunted, or he might be a victim of trauma. Like Frankenstein’s creature, Heathcliff has an uncertain sense of his origins and is left eternally in search of a home. He believes he will find this at Wuthering Heights, the remote and forbidding house of the novel’s title.

But Heathcliff is—like many of the Byronic heroes who entered the pages of fiction following Polidori’s The Vampyre—doomed. When his beloved Cathy dies, he descends into cruelty and dies himself after being visited by her ghost.

The novel ends with a vision of the tragic pair’s phantoms haunting the desolate Yorkshire moors they once roamed. One character, keen to reassure himself that they are at peace, watches over their graves and asks himself, “how anyone could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth” (Brontë 1996, ch. 34), but the ghostly lovers have had a long, unquiet afterlife.

4. Bleak House, Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens is not thought of as a Gothic author in the vein of Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker, although his writing featured ghosts (A Christmas Carol), spooky graveyards and ruined houses (Great Expectations), and disappearances in a cathedral crypt (The Mystery of Edwin Drood).

But Dickens’s most important contribution to Gothic literature was Bleak House (1852-53). Victorian London has been one of the most popular settings for Gothic literature ever since the Victorian period itself, and this is thanks to Dickens’s depiction of the city in Bleak House as a place of fog, dirt, and dark alleys.

The novel revolves around the interminable legal case of Jarndyce vs. Jarndyce, a dispute over a will. The fog that swathes all of London is a physical manifestation of the murkiness that masks all the intricacies of the case. When Dr. Jekyll or Dorian Gray roam the dim streets of London in later novels by Robert Louis Stevenson and Oscar Wilde (the grey atmosphere matching their moral ambiguity), they move through a Gothic London first put onto paper by Dickens.

5. Carmilla, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu

Predating Dracula by 25 years, Carmilla was a vampire story with an important difference: the vampire was a woman. In the late 19th century, it was in many ways more predictable for an author to make their vampire female, given the prevailing fascination with the femme fatale and a widespread association between seductive women and disease or death. But what was even more remarkable about Carmilla, in Le Fanu’s novel, is that her primary victim is also female.

Le Fanu’s novel is typical of the Gothic genre (and of science fiction, which had been developing alongside the Gothic since Shelley’s Frankenstein) in that it uses a frame narrative. The grisly tale of the young Laura, who is seduced by a mysterious visitor to her family’s castle, is presented as enclosed within the scientific notebooks of Dr. Hesselius, who is researching the occult.

This framing became a typical device for Gothic authors to create verisimilitude, or a sense that their stories really have taken place, as a way of playing with readers’ willingness to believe.

6. Dracula, Bram Stoker

Vampires had been seducing characters in fiction long before Dracula was published in 1897, but with Bram Stoker’s novel, the vampire seduced the reading public once and for all.

Like Le Fanu, Stoker was Irish, and it is possible to read these tales about the decaying landed gentry, wasting away in ruins and threatened by modern life, as allegories for late-19th-century Ireland as it fought to shake off British rule.

There are also stories in Irish folklore about vampire-like figures, whose thirst for blood was exacerbated during the Irish Famine. Although Stoker took the name Dracula from a history of Romania, it is a tantalizing coincidence that the Irish term “droch-fhoula” connotes bad luck or bad blood.

Whether we read it as an allegory about Irish nationalism, a comment on the spread of capitalism, a prescient meditation on attitudes towards foreign ‘others’ amid the decline of the British Empire, or a study of the late-19th-century concept of degeneration which took in negative stereotypes on women, Jews, and the mentally ill, Dracula is undeniably gripping.

Its narrative is even more elaborate than Carmilla, told through a series of letters, diary entries, and documents that make it difficult to establish a unitary perspective on who or what Count Dracula really is.

What is certain is that Stoker’s version of the vampire, closer to Polidori’s suave aristocrat in The Vampyre than the creatures of folklore, became definitive. Vampires are always seductive, and in the case of Le Fanu’s Carmilla, the reason is obvious: Carmilla is incredibly beautiful, constantly sidling up to the protagonist, Laura, and caressing her. The female vampires in Dracula are similar, but Count Dracula himself is colder and more fear-inducing, which makes his hold over the characters all the more disturbing.

7. The Beetle, Richard Marsh

The Beetle may be the least known work in this list, although for a while after its publication in 1897, it outsold Dracula, also published that year. Like many great Gothic works, it imagines something cursed at the very heart of ordinary society, and pits the well-to-do alongside the dispossessed and the monstrous.

One of the odder Gothic fictions published in the 19th century, The Beetle might be best explained through its similarities and differences to Dracula. It is also about a superhuman, shapeshifting creature who physically—and, it is heavily implied, sexually—dominates its victims. However, in this case, the creature is known as The Beetle (even the very mention of its name reduces characters to nervous wrecks).

While the source of the foreign threat in Dracula is Eastern Europe, in The Beetle, it is Ancient Egypt. While Count Dracula targets ordinary people in the seaside town of Whitby, the Beetle targets a member of Parliament.

A prime example of a late-19th-century novel open to postcolonial readings, The Beetle moves towards the revelation that The Beetle is pursuing this politician because he wronged the gods of Ancient Egypt while visiting Cairo. This representative of the British ruling class, lured by the exoticism of Egypt, attacked and enslaved a high priestess. Now, wreaking vengeance on him as the terrifying Beetle, she pursues and terrorizes him back at the heart of the empire.

8. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Robert Louis Stevenson

Like Frankenstein and Dracula, Stevenson’s 1886 novella Jekyll and Hyde is one of those Gothic tales that has transcended its pages and seeped into the wider culture. When we say someone has a Jekyll and Hyde personality, we mean that they have a very Gothic tendency to present a respectable front in everyday life that veils a murky true self.

Victorian London is the perfect setting for this tale of intrigue, which toys with the tropes of detective fiction as its narrator pursues the mysterious Mr. Hyde through the foggy back streets of London, to discover the secret of his connection to the upstanding Dr. Jekyll.

Through an intricate narrative, constructed out of various bystanders’ accounts and documents, we eventually discover the horrifying truth: Hyde is Jekyll’s own creation, embodying the darker side of his character.

Stevenson’s novel marks a shift inwards in Gothic literature, towards a concern with the psychological. Here, evil does not lurk on foreign shores or in strange, part-human creatures. It lies within the most ordinary human being, in the very center of British society.

The fact that we never quite find out everything that Jekyll gets up to when he transforms into Hyde only increases the story’s Gothic credentials. We know that Hyde is violent, even murderous, but as for Jekyll’s initial desire to live a double life? That is for the reader to speculate.

9. Hauntings, Vernon Lee

Dating from the same period as Jekyll and Hyde and Wilde’s Dorian Gray, Vernon Lee’s collection of stories, Hauntings, is less well known but shares with them several subjects and themes.

Lee (pseudonym of Violet Paget) was an expert on the Italian Renaissance and aesthetics, and wove this knowledge into her Gothic tales of young men, usually scholars or artists, haunted by relics or artworks. In these stories, the distant past comes to life in the present; or rather, the protagonists’ terrified encounters with artworks prove that the past can never truly be laid to rest.

A murderous femme fatale from medieval Italy lives on in her irrepressibly seductive portrait (a link to Dorian Gray and Robert Browning’s poem ‘My Last Duchess’); a sculptor models his Venus on a foundling who seems like the vengeful goddess come to life.

An ailing woman gazes at the portrait of her Elizabethan ancestor and believes that she is her reincarnation, put on this earth to achieve posthumous revenge by conspiring with her poet lover against her husband. A composer working on his opera in Venice is pursued by the enchanting voice of a long-dead castrato. In each story, the protagonist’s compulsive fascination with the past causes their ruin.

Lee wrote a preface to Hauntings explaining that the ghosts in her stories are “spurious ghosts (according to me the only genuine ones)” (Lee 2006). These ghosts live “on the borderland of the Past,” “only in our minds,” and are far more chilling than supernatural ghosts because of their connection to reality – particularly the reality of the human mind.

Each of her stories leaves open the possibility that no supernatural goings-on have actually occurred, and that the terror is only in our heads.

10. The Turn of the Screw, Henry James

Like the stories in Vernon Lee’s Hauntings, Henry James’s novella The Turn of the Screw amps up the terror by remaining ambiguous about whether its strange happenings are merely a figment of its narrator’s imagination.

Like so many great Gothic stories, the novella has a frame narrative, purportedly read around a cozy fire one Christmas Eve. The main narrative is the account of a governess who is hired to look after a well-off man’s niece and nephew, who seem to be under the ghostly influence of two of the house’s former staff members.

But are these ‘real’ ghosts, or what Lee would call ‘spurious’ ones? James introduces into the Gothic genre a tantalizing ambiguity about whether its supernatural creatures are seen by all, some, or none of its characters.

By the end of the story, we might deduce that the mischievous Miles and Flora have invented the ghosts to play a trick on their naïve new governess. We might feel that they have experienced some kind of trauma at the hands of their former governess, Miss Jessel, and her companion, Peter Quint, and are jointly hallucinating lingering visions of them.

Or, given a climactic scene in which Miles seems to see a ghost and the governess’s over-protective actions lead to him collapsing in a fatal swoon, we might wonder if it is the governess who has been imagining the ghosts all along. Are they manifestations of her own anxieties, her unease about the role she has to fill and about whatever took place between Jessel and Quint to lead to their dismissal?

James’s narration is brilliantly poised between all of these possibilities, allowing us to enjoy the story as straightforward Gothic horror, or to read between the lines of the governess’s narration a creeping sense that she is conjuring up these ghosts as a pernicious form of control.

11. Rebecca, Daphne du Maurier

Daphne du Maurier’s 1938 novel owes a lot to James’s Turn of the Screw: a young woman comes to an old house haunted by the memory of its former inhabitants, into whose shoes the young woman seems destined to step.

So overpowering is the ghost in this case that the novel is actually named after her, not the narrator, whose name we never find out. She is merely the second Mrs. de Winter, unsuspecting bride of the wealthy, brooding Maxim.

Rebecca is another example of psychological Gothic. Its creeping terror revolves around the narrator’s curiosity about how Rebecca died. A curiosity that is spurred by the brilliantly malign housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, who pours poison into her ear about how she will never compare to the first Mrs. de Winter.

But there are also more traditional Gothic touches, such as the haunted house, Manderley, a brooding hero, dark secrets which pursue those who hold them, and a spectacular blaze which engulfs Manderley once its hidden past has come to light.

12. The Haunting of Hill House, Shirley Jackson

Ultimately, the distinction between psychological Gothic and traditional Gothic is not clear-cut, since Gothic literature is always about the psyche, and how our surroundings can seem to take on the darkness or monstrosity we feel inside.

This is particularly true of Shirley Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House. Jackson plays with long-established Gothic conventions, turning our attention from the question of whether the house is haunted to why the characters believe or disbelieve it is.

Jackson perfectly captures the way a house can take on human qualities when its inhabitants fear some kind of ghostly presence. She writes in the novel’s opening: “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within.”

Jackson’s interest, and that of all Gothic literature, is how these “conditions of absolute reality” can alter depending on our psychological state. The house becomes, as one reviewer writes, “the antagonist of the story,” even while Jackson’s description leads us to think there is nothing out of the ordinary about it. It is not, as in other Gothic tales, a romantic ruin or ramshackle hut teeming with cobwebs: just a normal house.

It is this plausibility that makes Jackson’s novel so effective. By taking for her protagonists a collection of characters who believe in the occult but are desperate for proof, Jackson situates her story in a world we can easily enter. These characters might as well be the readers, their pulses quickening at the tiniest sign of paranormal activity.

13. It, Stephen King

A classic feature of Gothic literature is the unnamable, the undefinable: the thing which is so horrifying that language becomes inadequate. At the center of many Gothic mysteries is something which is better left undisclosed—letting the reader’s imagination run riot. The monster, if there is one, can only be referred to as it.

Many of Stephen King’s novels could have made this list. The Shining (1977) transplants the traditional haunted house trope to a spooky, deserted hotel. Misery (1987) hinges on the perennial Gothic theme of obsession.

It (1986), like several other King novels, has child protagonists, which makes its exploration of the imagination and reality all the more potent. Moreover, these children are bound together through being outsiders. They are ripe victims for the entity known as It, a shapeshifting creature which appears to each of them in an array of horrifying guises.

King’s narrative may not be composed of found documents like earlier Gothic tales such as Dracula and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. However, it is equally complex, a sprawling story that follows the group of terrorized children as they become adults and try to shake off their childhood trauma. Like in all the best Gothic stories, though, this part of their past can never truly be buried. The constantly shapeshifting It remains, eternally manifesting each adult’s deep-rooted fears.

Bibliography

Brontë, Emily (1996). Wuthering Heights. Project Gutenberg edition.

Lee, Vernon (2006). Hauntings: Fantastic Tales. Project Gutenberg edition.