Known all over the world as the king with six wives, Henry VIII was the second Tudor monarch in England. His reign left indelible imprints on British history. Often portrayed in popular media as a mercurial, irascible figure who would turn on those around him in a flash, Henry VIII did have certain consistent aims throughout his reign. Although he was intent on projecting an image of absolute power, other important individuals—ministers, clerics, and Henry’s wives—also made their mark on the nation’s transforming political landscape.

The Young King: Henry VIII

The fact that Henry VIII was named Henry Tudor, like his father, King Henry VII, might make you think that he was the firstborn son and heir, always intended to inherit the throne. But Henry had an older brother, Arthur, named after the legendary king of Britain who, like the Tudor family, hailed from Wales. When Arthur Tudor died in 1502, the ten-year-old Henry became heir apparent and succeeded to the throne in 1509 upon his father’s death.

Henry VIII started off his reign determined to be everything his father had not been: not frugal but fun-loving, not a reclusive miser but a Renaissance man. Only 17 when he was crowned, Henry had a reputation for enjoying hunting and jousting, music and pageantry, and fine clothing. Reports spread across Europe that the new king was impressive to look at and not shy about displaying his wealth. At his coronation, Henry and his wife Catherine of Aragon, both bedecked in jewels, paraded through Westminster under a canopy of gold cloth.

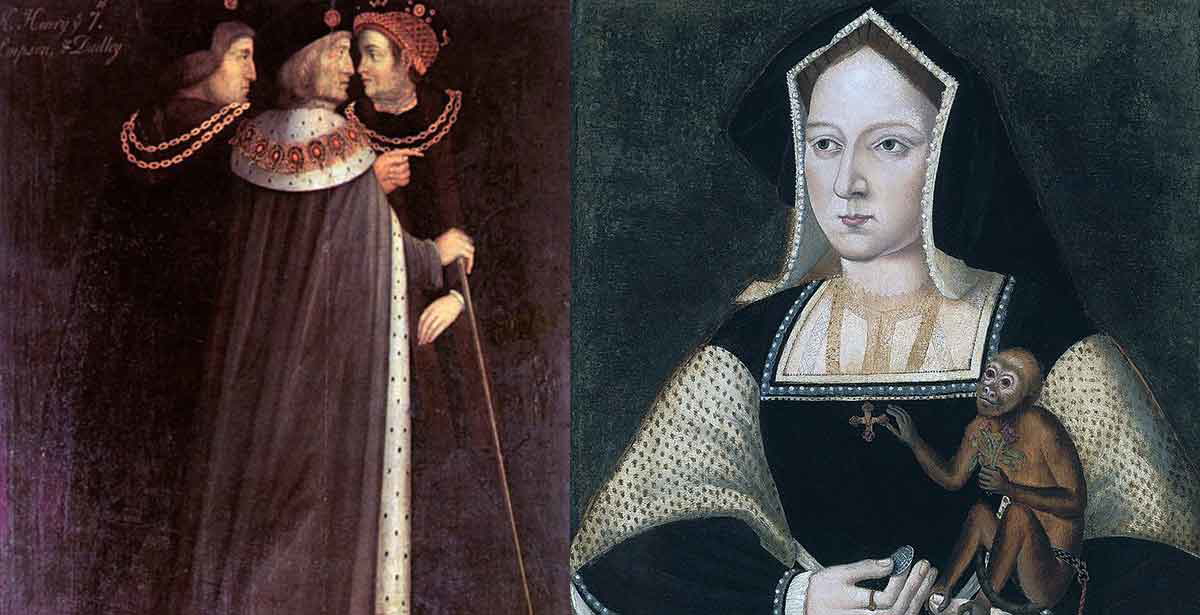

Henry VII had been a careful ruler, conscious of his position as the first Tudor king. The English throne had come to him on the battlefield at Bosworth during the final battle of the Wars of the Roses when he and his Lancastrian troops defeated the Yorkist king Richard III.

Although the victory put an end to the fighting between the two houses, Henry VII was by no means secure on the throne, and there were multiple attempts to put forward pretenders. Perkin Warbeck, who impersonated Richard, the Duke of York and younger brother of King Edward V, one of the missing Princes in the Tower, got as far as having his claim officially recognized by supporters in Burgundy and Ireland. When he gained enough support to mount an invasion at Cornwall, Henry had him imprisoned and later hanged.

By marrying Elizabeth of York and having four children (Arthur, Henry, Margaret, and Mary), Henry VII hoped to secure the future of the dynasty. By adopting the Tudor rose—a combination of the oft-used white rose of the Yorkists and the slightly less frequently seen red rose of the House of Lancaster—he signaled to the nation that peace and unity had come at last.

Foreign Policy: Henry VIII’s Friends and Foes

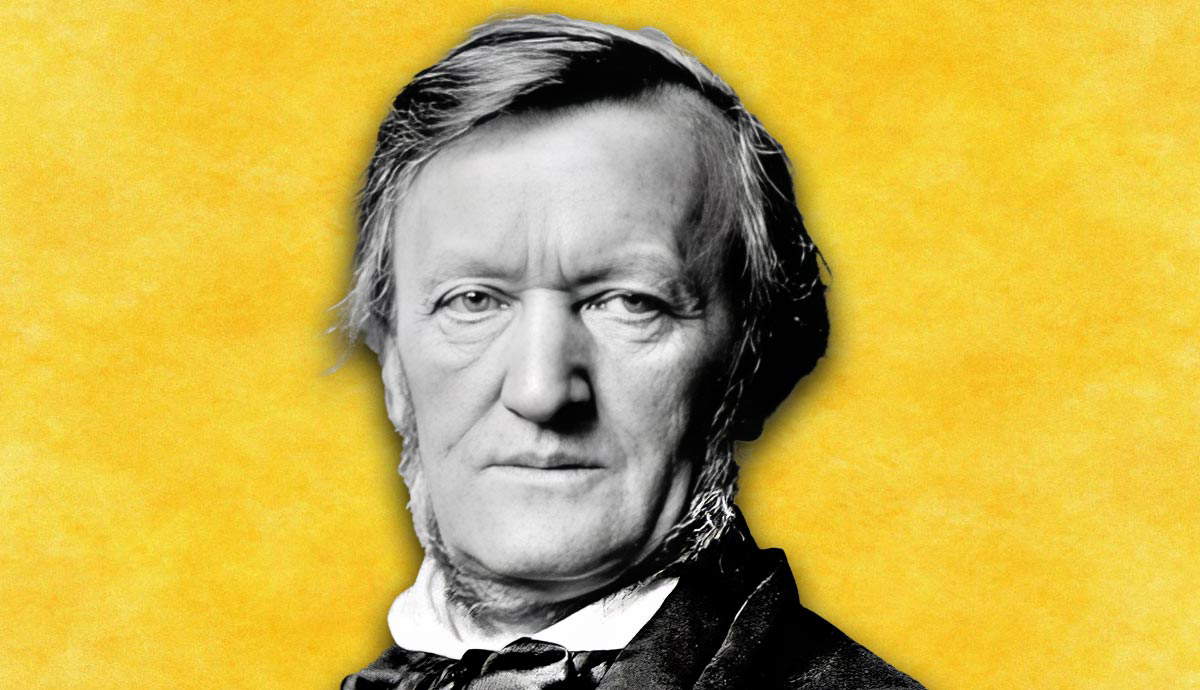

Henry VIII inherited the throne far more smoothly than his father had done, and what was more, he came to an unprecedentedly wealthy throne thanks to his father’s economic policies. Through a combination of strategic treaty-wagering and tax-raising, Henry VII had made the English monarchy richer than it had ever been. This had not made him hugely popular. One of his son’s first decisive acts as king, after gauging which way the public opinion was swaying, was to charge Henry VII’s notorious tax collectors, Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley, with treason and have them executed.

Acceding to a relatively stable throne, in both dynastic and economic terms, left Henry free to pursue foreign policy exactly as he wished. Would he take after his father and prefer to focus on domestic prosperity, maintaining good relations with neighboring states via mutually beneficial marriages, or would he offer a display of strength by pursuing war?

Although he initially followed his father’s lead in maintaining a friendship with Louis XII of France, Henry soon reverted to the longstanding wish of English monarchs to expand their kingdom across the Channel. In 1513, aided by an alliance with Spain via his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, England invaded France, besieging and capturing the towns of Thérouanne and Tournai (now in Belgium).

At the same time, another traditional rivalry flared up again. Although Henry VII had signed the Treaty of Perpetual Peace with Scotland in 1502, his son’s invasion of France prompted the Scottish king, James IV, to honor the Auld Alliance between Scotland and France by declaring war on England. Other factors motivated the rivalry between England and Scotland. The border was under constant dispute (in contrast to the more decisive border between England and France provided by the Channel), and English kings had been declaring themselves rulers of Scotland for centuries.

James IV may also have objected to the young, upstart Henry VIII joining the so-called Catholic League against France (assembled by Pope Julius II) since James himself had only a few years earlier been given the title of “Defender of the Faith” by the pope. Since Henry was away with his armies in France, Catherine organized the troops to be sent to Scotland, and the Battle of Flodden, a decisive victory for England at which James IV himself was killed, was fought on September 9, 1513.

Within five years of ascending to the throne, Henry had fought major battles on two fronts and emptied the treasury. However, there were signs that he might pursue foreign policy through less bellicose means. Louis XII of France died in 1515, succeeded by Francis I, who was only a few years older than Henry. The two kings formed a friendship, starting with the peace terms negotiated by Henry’s minister, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, in the Treaty of London in 1518.

They then ostentatiously displayed their friendship in 1520 at an event known as the “Field of the Cloth of Gold,” where Henry, Francis, and their retinues met for a fortnight of entertainments. The ostensible aim might have been to prove their dedication to peace (although they indulged in a one-on-one wrestling match, which Henry lost). Still, as the name suggests, the “Field of the Cloth of Gold” was really about parading their wealth. Minor palaces were erected solely for the event and adorned with the finest stained glass. Henry brought along two monkeys gilded with gold leaf, and the fountains flowed freely with red wine.

Although, for primarily economic reasons, Henry was not able to wage war constantly, and there were periods of peace with both France and Scotland, his aims to expand the reaches of England’s territories into both countries were some of the most consistent aims of his reign. Major campaigns in France and Scotland followed in the 1540s, the last decade of Henry VIII’s reign, leaving all three of his legitimate children (all of whom came to the throne in succession) to continue the wars in both countries.

How Henry VIII Used His Ministers

Like other rulers of his day, Henry VIII considered himself divinely chosen to be king, a role that not only meant he had absolute power but made his entire person, body and soul, sacrosanct. In contrast to the theory of Niccolò Machiavelli‘s The Prince (written c. 1513, published 1532), which advised on how to navigate courtly power dynamics with wisdom and cunning, Henry subscribed to the more absolute notion of the “divine right of kings,” which made the monarch answerable to no one but God. In theory, the monarch was also accountable to the pope, God’s representative on earth—but Henry would come to see himself as having a privileged position as God’s representative himself, which not even the pope could contravene.

However, Henry’s reign is notable for the critical role played by several of his ministers. Thomas Wolsey was royal chaplain to Henry VII and was already beginning to become involved in diplomacy when Henry VIII came to the throne. As almoner—in charge of distributing alms to those in need—in the Privy Council, Wolsey had Henry’s ear and was constantly on hand to resolve administrative issues that were of little interest to the young king.

In 1514, Wolsey became Archbishop of York, one of the highest clerical offices in the nation. His rise to fame was notorious. The nobles resented him for his humble birth (apparently, he was a butcher’s son) and his adeptness at managing court politics and bringing down his rivals. Gathering bishoprics like chess pieces, he amassed such power and influence—not to mention money—that he was branded Alter Rex or “other king.”

Such a position, especially alongside an absolutist ruler such as Henry, was, of course, unsustainable. Wolsey eventually fell foul of the king, taking charge of diplomatic matters in a way that hinted, perhaps, at an intention to usurp his master. The “Great Matter” of Henry’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon, which Wolsey was unable to attain, was the final straw. Having retreated to his lands in Yorkshire, Wolsey was called back to London to face charges of treason but died of natural causes on the journey.

One of Wolsey’s disciples, the lawyer and former merchant Thomas Cromwell, had taken notes on the cardinal’s rise and fall. Like Wolsey, Cromwell was adept at managing the king and court. He became Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1533, followed by a series of ever more prominent governmental positions, including Principal Secretary in 1534, Lord Privy Seal in 1536, and Vicegerent of Spirituals—in recognition of his role in the country’s religious transformation, more on which below—also in 1536. For a few years, Cromwell occupied a position comparable to the modern concept of the prime minister, sitting atop the most important councils and having (almost) the final say on executive decisions about the realm.

Like Wolsey, though, Cromwell could not sustain this position forever. Members of the old noble families resented him, too, for his humble birth and rapid rise through the ranks. When turbulent times in the Reformation coincided with Henry’s disastrous marriage to Anne of Cleves (orchestrated by Cromwell), Henry was easily convinced that his minister had grown too powerful. Convicted without trial for treason, ostensibly for over-zealously promoting Protestant reforms, Cromwell was executed on July 28, 1540.

Henry’s relationship with his ministers was, in the long run, transformative, informing his daughter Elizabeth I’s carefully judged reliance on ministers such as Robert Cecil and Francis Walsingham. Ultimately, though, the rise of apparently ordinary people like Wolsey and Cromwell suggested—to many reflecting on the question a century later, as the Parliamentarians challenged the Royalists—that perhaps the monarch might be fallible and ministers more capable.

Henry VIII’s Wives

Henry VIII stands out in the history of the British monarchy for having had six wives. Of all the kings since the Norman conquest, a handful had married twice: not an uncommon occurrence considering the higher likelihood of women in the medieval period dying in, or shortly after, childbirth. This was the fate of one of Henry’s wives, Jane Seymour.

On the whole, though, we can hardly say that Henry married six times because of women’s low life expectancy—there were myriad other reasons. One was that amorousness was among the qualities befitting the Renaissance man Henry sought to embody. As a young man, he wrote love poetry and composed and performed songs to woo the women at court (although it is probably not true that he wrote Greensleeves for Anne Boleyn, he did write her several love letters).

Henry is known to have had affairs during his 20-year marriage to Catherine of Aragon, including with Mary Boleyn. However, it was only when he fell for her sister Anne that he rejected the prospect of another mere affair and pursued an annulment with a view to remarrying. This was partly a result of his frustration that Catherine’s numerous pregnancies had resulted in just one living child, a daughter (although, given his subsequent difficulties conceiving with later wives, it is likely their fertility problems were also down to him), and partly a result of Anne Boleyn’s force of character. As much as Wolsey or Cromwell—two of her most important adversaries—Anne knew how to get through to Henry, and she had a significant influence on events at home and abroad, most notably through her support of the Reformation.

Not until his sixth wife would Henry have another consort who made a considerable contribution to the running of the country. Having had Anne Boleyn executed on charges of adultery with five men (on evidence, it is possible that Cromwell, along with other rivals of Anne’s, helped to bring forward), Henry then married Anne’s lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. The longed-for son, the future Edward VI, was born just over a week before Jane died.

Henry’s fourth and fifth marriages, to Anne of Cleves and then Catherine Howard, sum up his mercurial character, wavering between a susceptibility to be dominated by advisors and a willful ignorance of those around him. Cromwell and other councilors had recommended Anne of Cleves to strengthen England’s relationship with the Protestant German states. However, when she arrived in the country, Henry was unimpressed with her appearance and had the marriage annulled within six months. The idea that Henry simply found her unattractive has recently been challenged with the suggestion that Anne’s unusual German fashions were at fault; at least, Henry immediately reverted to the more familiar English charms of Catherine Howard.

Neither Anne of Cleves nor Catherine Howard influenced Henry’s reign beyond providing evidence that the aging, ailing king was increasingly volatile. Henry had suffered a life-threatening jousting injury in 1536, which left him with a brain injury and constant abscesses on his leg.

After Catherine Howard, like her cousin Anne Boleyn, had been executed for adultery, it was a brave woman who agreed to become the king’s sixth wife. Unlike his previous wives, Catherine Parr was older and wiser and had already been married twice before. A strong advocate of education—both for women and illiterate worshipers who, before the Reformation, had prayed a Latin mass with little conception of what they were saying—Catherine oversaw the education of Henry’s children, Mary, Elizabeth, and Edward.

In 1544, Parr translated into English a Latin work by Bishop John Fisher. The work was published as Psalms or Prayers taken out of Holy Scriptures, and included a “Prayer for the King,” which remains in the Book of Common Prayer used by Anglicans today. Henry’s stance on Protestantism in the 1540s, however, was by no means wholly positive, and Catherine was careful to present herself as moderate and unconcerned with the more extreme reforms taking place in Europe.

Although Catherine Parr married the king when he was most unpredictable, she managed to weather his storms. She even talked him down after he issued an arrest warrant against her. She survived him by just over a year.

Reformation and Riots

The most important way Henry VIII transformed England was by breaking with the Vatican and instituting the Church of England. It is still debated how much of this was motivated by his wish to divorce Catherine of Aragon (which the Pope would not grant), how much he shared the views and aims of European reformers such as Martin Luther, and how much he and his councilors attempted to limit the vast power and wealth of the clergy in England (particularly as landowners).

Back in 1521, Henry had been given the title of “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X for condemning Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses as heretical. But by 1531, Henry had created for himself the title of “Supreme Head of the Church of England,” sharing Luther’s critiques of the Papacy but viewing himself, as a divinely ordained ruler, as solely capable of taking charge of the religious well-being of his people. In 1534, the unprecedented Act of Supremacy declared that the monarch was the sole head of the church. By 1536, Henry had appointed administrators, led by Cromwell, to address various abuses in monasteries and convents across England, Wales, and Ireland.

The dissolution of the monasteries, as it became known, was purportedly a program of reform, looking into the possibility that some religious orders were misusing funds, promoting fraudulent relics, and covering up vice. Given that monasteries and other religious institutions owned a quarter of the cultivated land in England, though, there was a clear impetus for Henry VIII to have them shut down and their assets transferred to the crown. Every abbey and priory in England was dissolved (around 800), vast amounts of gold and silver were seized, and the buildings themselves, in many cases, were dismantled or damaged.

Many of these monasteries and abbeys were in the north of England, where continued support for Catholicism combined with grievances against Henry’s rule, particularly the detrimental effects of his warmongering. In 1536, thousands of insurgents banded together in what became known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. One of the most widespread revolts of the entire Tudor period, it resulted in over 200 people—both nobility and ordinary civilians—being executed.

Objections to Henry’s reforms continued, however, and the remainder of his reign was characterized by religious divides, both on a personal and political level. As suggested by his willingness to prosecute his own wife, Catherine Parr, and to have Cromwell executed, both for subscribing to Protestant beliefs, Henry aimed to sustain something very close to the Catholic faith in England, just a version operating independently of Rome. When he lay dying in January 1547, he saw his confessor and received communion in accordance with Catholic rites, although the priest in attendance was the Protestant Archbishop Thomas Cranmer.

This mixture of old and new faiths at Henry’s deathbed set the tone for his legacy. His three children would each take distinct approaches to the nation’s religious life, from the radical Protestantism of Edward VI to even more radical attempts to bring the country back to Catholicism by Mary I (nicknamed “Bloody Mary”). On the other hand, Elizabeth I pursued a “middle way.”

Although Protestantism was nominally the only faith in England, many recusant Catholics continued to practice their faith. Staunchly Catholic Spain used England’s heresy as grounds for mounting several armadas in the late decades of the 16th century.

Henry VIII & the Tudor Dynasty

Did Henry VIII, in the end, fulfill the hopes at the beginning of his reign that he would establish the Tudor dynasty and bring stability to the country at last? Certainly, there were tumultuous moments. All of the money Henry VII had managed to wring out of the nation’s landowners, Henry VIII spent on wars in Scotland and France, achieving some victories on the battlefield but little territorial expansion. The Reformation was a long and rocky road, and his six marriages made him notorious in all the wrong ways.

But were it not for Henry VIII, the Tudors may well have remained a footnote to history or a minor dynasty with little staying power. As it is, they are probably the most famous family to have ruled Britain. Henry’s desperation for a son, so important a factor during his life, becomes ironic in the context of his legacy, especially when we think about how significantly his daughters shaped British history.

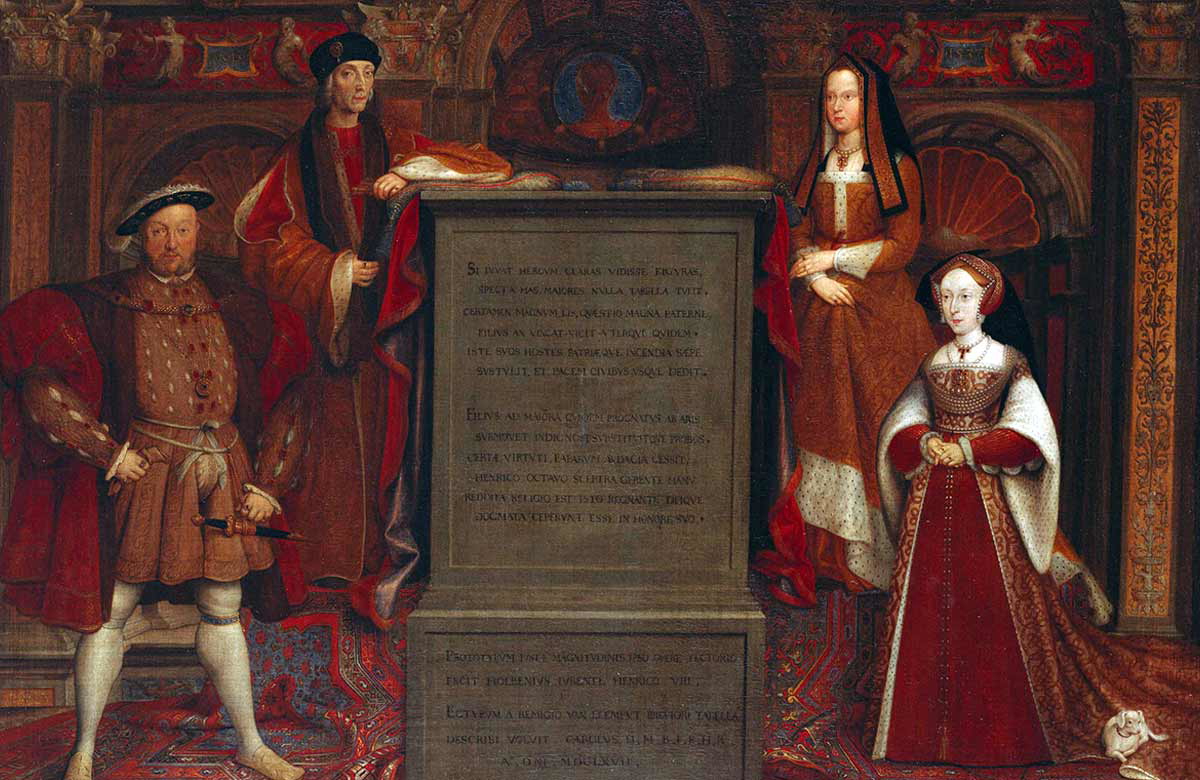

Perhaps Henry had some prevision of the lasting fascination of the Tudors when he commissioned Hans Holbein to create a mural for Whitehall Palace, giving a fictional depiction of himself, as an adult, with his parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, and his wife, Jane Seymour. The choice of figures is a testament to his conviction that the Tudor dynasty was, at last, secure.