Many people are confused and think that Wales, in the United Kingdom, is a part of England, something that angers most Welsh people due to the turbulent history between the two countries. Wales has a long and fascinating history, all of its own, characterized by consistent struggles, especially with its English neighbor. Although the country was only formally recognized with its current boundaries by Henry VIII in 1536, the area has always been culturally unique. Below is a brief history of Wales and its people.

From the Stone Age to Celtic Tribes

The first evidence of homo sapiens living in Wales can be found in the skeletal remains of the “Red Lady of Paviland,” which were discovered in 1823. Originally thought to be a Roman-era woman, later analysis revealed the remains to that of a man dating from around 33,000 years ago. Arrowheads and tools were found nearby, suggesting the individual was likely a hunter-gatherer during the last Ice Age.

During the Mesolithic period (approximately 8,000 BCE), Wales shifted from an Ice Age to a fairly hospitable climate. Tombs found in Pembrokeshire indicate that there were many communities in the coastal regions.

Wales appeared to have flourished during the Bronze Age (c. 3300-1200 BCE), with the largest known prehistoric mine being located in Llandudno. Metalworking in Wales was cutting-edge for the time. Tools, especially ax heads made in Wrexham, have been found in Brittany and Germany, demonstrating that Wales was part of a larger Bronze Age trading network.

Gold was also mined in Wales, and the Mold Gold Cape, currently housed in the British Museum, is the most famous example of fine gold working from Wales. Additionally, the bluestones at Stonehenge probably came from Pembrokeshire. Both the reason for the stone formation in Wiltshire and how it was constructed have puzzled historians for generations.

Based on differing styles of metal tools, Wales seems to have been divided into five regions in the Bronze Age, very similar to the tribal regions that existed when the Romans arrived. According to the Romans, these tribes were the Silures, Demetae, Deceangli, Ordovices, and the Gangani. Hill forts became increasingly common in the Iron Age (c. 1200-600 BCE), with around 600 being constructed, reflecting an increase in wealth and in conflict between local groups.

Roman Wales

When the Romans arrived in Britain in 43 CE, they conquered vast amounts of modern England quickly, but ran into trouble at the border of Wales in 48 CE. It would take 25 years for a conclusive Roman victory against the Welsh tribes due to the unprecedented mountainous landscape and guerilla warfare tactics of the Welsh.

After many small-scale skirmishes along the border, Caractacus, the Prince of the Catuvellauni tribe from Essex, escaped to Wales. Having led resistance in England, he rallied the Silures and Ordovices. The opposing Roman and Welsh sides alternated between success and defeat, but by 74 CE, the Romans had conquered most of Wales.

The sources suggest that Roman influence over Wales was not as strong as it was in England due to the unfavorable geography of the area. However, gold was mined, and roads and forts were built. Notable fortresses include Isca Silurum, now known as Caerleon, near present-day Newport, which housed an estimated 5,600 soldiers. Roman urban sites were less common. Only five have been found, all in the south.

The Age of Saints

The coming of Christianity to Wales happened in the 4th century. The druids, or Derwydd in Welsh, who were the religious officials of the pre-Roman Celtic religion, were largely wiped out by 60 CE. Nevertheless, the native religion largely continued. This was possible in part due to the Roman custom of fusing indigenous deities with their own.

Traditional Welsh mythology was passed down through word of mouth and was eventually transcribed in the 12th and 13th centuries as the Mabinogion, which introduced the world to key literary figures such as King Arthur and Merlin. Originally, Christianity was rejected by the Romano-Welsh, and two men, Aaron and Julius, were martyred at Caerleon for their beliefs in 304 CE. However, by the end of the 4th century, Christianity was the official religion of the Roman Empire and, therefore, Wales.

The 5th and 6th centuries are often referred to in Wales as the Age of Saints, brought about by invading pagan Saxons. When the Saxons arrived in the British Isles, Romano-British communities were pushed to the edges of Britain, namely Wales and Cornwall, where they maintained their version of Christian religion. Those who were influential in the preservation of Christianity were called “saints,” but without formal canonization.

Perhaps the most famous of these Welsh Saints was Saint David, a bishop who performed miracles across Wales. He is one of only two Welsh Saints formally added to the Roman Calendar of Saints. He was declared the Patron Saint of Wales in 1120.

The Medieval Period

The Vikings arrived in Britain in around 793, but their first raids in Wales were nearly sixty years later. Some coastal place names preserve Scandinavian origins, and some sources suggest that there were a handful of Viking settlements along the Welsh coastline, but the Norsemen had relatively little impact in Wales compared to England, Scotland, and Ireland. In short, the Vikings raided coastal communities but left Wales mostly untouched as Rhodri Mawr, King of Gwynedd in the north of Wales, continually fought against them. This earned him the epithet “Mawr,” meaning the “the great.” King Rhodri won a famous battle in 856 against the Scandinavians, but he is thought to have been killed by the Anglo-Saxons in 878.

A later king of Gwynedd, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, was able to unite the whole of Wales under his leadership between 1055 and 1063. But he was killed by English forces sent by Harold Godwinson, and Wales returned to its former organization as multiple smaller kingdoms. Harold Godwinson, or Harold II, was killed at the Battle of Hastings just three years later by the invading Normans.

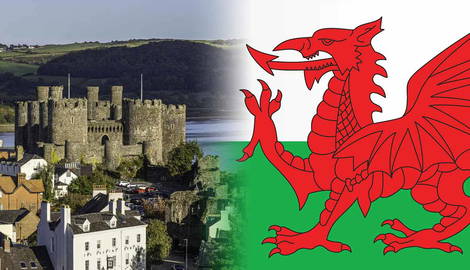

Under the reign of the new Norman king, William the Conqueror, military bases were set up along the Welsh border. Skirmishes were common, but William did not unleash his full force on Wales. However, upon his death, Norman lords divided much of Wales up between themselves and erected their trademark castles across the landscape, such as Cardiff Castle and Swansea Castle.

Following the death of Henry I, William’s youngest son, the Welsh princes refused to conform to the Anglo-Norman rule, which sparked a period of almost constant war until 1283. Wales united under Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, also called Llywelyn the Great, in 1193. He pushed the English out of north Wales and regularly fought off English invaders sent by Henry III.

Both Llywelyn’s son and grandson would succeed him and continue the Welsh Wars of Independence. But Edward I made the conquest of the Welsh his priority and launched three large campaigns across the border. Llywelyn’s grandson, also named Llywelyn, was the last king of Wales. He was killed in battle, and Wales was officially defeated. Edward I’s first son was born and named the first English Prince of Wales.

Welsh Resistance

Owain Glyn Dwr, born around 1354, claimed to be a descendant of Llywelyn the Great and garnered support for a new nationalist movement. Initially, Glyn Dwr was blessed with a relatively uneventful life. He studied in London, married the daughter of an Anglo-Welsh judge, and served as a soldier in the English army.

When Richard II, who offered favorable opportunities to Welsh nobility, was usurped by Henry IV, Glyn Dwr faced challenges at the English court. He proclaimed himself the Prince of Wales in 1400. Glyn Dwr was joined by the Tudur Brothers of Anglesey, an aristocratic Welsh family with close ties to Richard II, almost immediately. After many successful guerilla attacks from the Welsh, Henry IV introduced extremely harsh anti-Welsh laws, aimed at enforcing the supremacy of the English in Wales.

By 1403 the revolt had encompassed all of Wales and saw many Welsh people living in England return to the country to support the cause. But the Welsh successes were not to last. Glyn Dwr’s attempts at making international connections fell through and the English strategically blocked Welsh trade.

Ultimately, no one is completely sure what happened to Glyn Dwr, but his last unsuccessful attacks against the English happened between 1410 and 1412. His family was captured and Owain Glyn Dwr disappeared. Henry IV also died in 1413, and his son Henry V took a more conciliatory approach, offering pardons to the rebellion leaders, including Glyn Dwr’s son. Nevertheless, many leading Welsh families were financially ruined, great castles were destroyed, and there was an immeasurable loss of life.

The Welsh King of England

Henry Tudor defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Thus ended the War of the Roses and began the Tudor Dynasty. In the most unlikely sequence of events, Henry VII, a descendent of Ednyfed Fychan, steward of Llywelyn the Great and a relative of the Tudurs, and one of the most faithful allies of Owain Glyn Dwr just seventy years earlier, had become the King of England.

Henry VII’s father was Edmond Tudor, son of Owain Tudor, who had married the widowed Queen Catherine after the death of Henry V. Therefore Henry VII was descended from royalty on the Lancaster side of the War of the Roses. Henry VII was born in Pembroke Castle in an English-speaking area of Wales.

It is unlikely that Henry VII viewed his Welsh ancestry with much regard. He was a quarter Welsh, a quarter French, and half English, which was most important to his claim to the throne. It was the Welsh who adopted the king as one of their own, not Henry VII who promoted his Welsh roots. However, his amiability towards Wales was noted at his ascendency and throughout his reign.

Under Henry VIII, the 1536 Act of Union was passed. This effectively ended any Welsh autonomy and declared that the laws of England would apply to Wales, and that English would be the only language spoken in Welsh courts. Many of the Welsh upper classes could speak English, but those of lower social standing could not.

The main purpose of the Act of Union was to regulate the administrative system in the face of threats from England’s influential Catholic neighbors in Europe. But with the enactment, Henry VIII damaged the Welsh national identity, although it did allow for greater Welsh representation in Parliament. The Protestant Reformation also took place under Henry VIII, which saw Welsh religious lands handed over to members of the English nobility.

The English Civil Wars

The English Civil Wars began in 1642 and would not be conclusively over until 1651. The challenge was to define the balance of power between the king and parliament, and almost the entirety of Wales sided with King Charles I. At the Battle of St. Fagans, the largest battle to ever take place in Wales, the forces loyal to the king were decisively defeated because most of the Welsh troops were volunteers with primitive club weapons, whereas the parliamentarians were a well-trained unit. The new Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell began intensive reform in the Welsh Church and sought to drive out the superstitious beliefs.

Also in the 1600s, the British began to colonize the Americas and many of the people making the move across the Atlantic Ocean were from Wales. The first permanent colonies were established as early as 1609, but soon, due to the English Civil Wars and subsequent persecution of religious practices in Wales, many Welsh protestants flocked to New England. Many of these individuals traveled with the hope of setting up distinctly Welsh settlements, and a handful were successful for a time, such as Malad Valley in Idaho.

Then came the period of witch trials. Wales showed an indifferent attitude towards witch-hunting, with only five people executed for witchcraft between the 16th and 18th centuries. However, there was panic in the colonies. The first woman to be executed for witchcraft in the American colonies was Alse Young in 1647, who was thought to have emigrated from Wales.

Wales in a Changing World

The New World continued to develop and with it came the Golden Age of Piracy between 1690 and 1730. Many infamous pirates from this era came from Wales, such as Howell Davis and Bartholomew “Black Bart” Roberts. Black Bart was the most successful pirate of the age, as measured by the number of captured vessels.

These particular pirates actually knew each other well as it was Davis who captured the slaving boat Roberts was working on and forced him to join the pirate crew. The two became close, as Howell appreciated Roberts’ navigational skills. The pair spoke to each other in Welsh. But Howell would die in battle just six weeks after recruiting Roberts, allowing Roberts to become the crew’s new captain.

British colonization of the Americas continued and Welsh faces continued to play an active role. Lieutenant-General Thomas Picton was born in Pembrokeshire and was named Governor of the Island of Trinidad in 1797. Picton was feared for his volatile temper and cruel methods of punishment, earning him the nicknames the “Tyrant of Trinidad” and the “Blood-Stained Governor.”

He came under the scrutiny of the British Government after he ordered the torture of a girl, Luisa Calderon, who was no older than fourteen. Nevertheless, he was generally considered a hero. Picton had the conviction overturned and resumed his questionable governorship. His statue was removed from Cardiff City Hall’s “Heroes of Wales” gallery in 2020.

The slave trade persisted in the Americas, but by the 1770s, relations between Great Britain and the American coloniees had became strained, ultimately resulting in the American War of Independence. The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, and 16 out of the 56 men who signed the document were of Welsh descent.

The Industrial Revolution

When the Industrial Revolution began, Wales became a key player in Britain’s transformation. Mining and metal production in Wales brought great wealth to Britain. With economic growth in Wales came advancements in the form of railways, roads, and a huge increase in housing to match the expanding population. No later than 1851, two-thirds of Welsh families were financially supported by occupations outside of agriculture, making Wales the second most industrialized country in the world after England at the time. However, as a side effect, many of Wales’ formerly idyllic landscapes were destroyed.

The Industrial Revolution led to rising tensions among the working classes, particularly for the Welsh who worked in mines and factories. The Merthyr Riots erupted in 1831 in response to the lowering of wages for mine workers, and the protesters seized control of the town. When authorities took back control they killed an estimated 24 protesters and many of the leaders were arrested and sentenced to penal transportation to Australia.

The Rebecca Riots also took place between 1839 and 1842. This time the protesters were mainly agricultural workers who had been impacted by poor harvests and high taxes. The protesters first focussed on the toll gates as a visual representation of their taxes, and then turned on their landlords. This time the riots achieved tax rate improvements and some rent reductions.

Wales During the World Wars

Wales, as part of the United Kingdom, fought with the Allies in World War I. An estimated 275,000 soldiers from Wales fought, and there were 35,000 recorded casualties. The village of Frongoch housed an internment camp for German prisoners of war, which was also used to house Irish Republicans after the Easter Rising.

David Lloyd George was born to Welsh parents and grew up in Caernarfonshire, with Welsh as his first language. Lloyd George went on to become Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in December 1916 and led the country through the end of World War I, earning a huge amount of admiration. Nevertheless, his popularity declined in his later years as he routinely praised Adolf Hitler, although this was predominantly because of his view that the Treaty of Versailles was too harsh on Germany.

Unemployment in Wales grew quickly after World War I, with around 28% of men being out of work. This, coupled with the independence of other European countries after the war, led to new nationalistic politics in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. Plaid Cymru, meaning “the National Party of Wales,” was founded in 1925. Welsh nationalism soared further after it was decided that a bombing school would be established in north Wales. Over half a million protesters came out to demonstrate their anger.

In World War II, Wales again fought alongside the rest of the UK and the bombing school was used continually throughout the war efforts. The German Luftwaffe bombed Wales, especially Cardiff Docks, as it was a strategic coal port.

The Continued Fight for Welsh Rights

In the 1930s, Aneurin Bevan, born in Tredegar, Wales, was increasing in popularity as a politician. In his early days, he was a union activist and a leader among Welsh miners during the General Strike of 1926. In 1929 he became a Labour MP. He was known for his socialist ideas by the time he was appointed Minister of Health in 1945. Bevan established the National Health Service in 1948, which provided free medical services for everyone in the UK. Bevan repeatedly fought for working-class rights before he retired as Minister of Labour due to the introduction of fees for prescriptions within the NHS.

Mining remained a significant part of the economy in Wales, with coal at the center. However, the industry faced difficulties in the later 20th century. Margaret Thatcher’s ascension as Prime Minister would spell disaster for many Welsh communities and fuel political movements towards Welsh nationalism again.

At first, Thatcher was a popular figure in Wales, but her plan to close twenty coal mines, that would put 20,000 Welsh people out of work when unemployment was already high, was unsurprisingly unwelcome. Three-quarters of all the 190,000 Welsh miners walked out on strike in 1984. The strike went on for a year, but was eventually defeated, and with it trade unionism and left-wing politics. Thatcher also privatized railways, gas, and water utilities, which proved especially unpopular in Wales. On a press trip to the Welsh Valleys, Thatcher told journalists to “cheer up” when they questioned her on the heavy unemployment in Wales.

The closures of the coal mines over the next twenty years brought about poverty for thousands in Wales and the fight for Welsh rights intensified. The Welsh Language Act was passed in 1993, which made the Welsh language equal to the English language in Wales after hundreds of years of persecution. This was swiftly followed by Wales and Scotland gaining their own devolved Parliaments in 1998 after a referendum the previous year.

Since the establishment of the Senedd Cymru (Welsh Parliament), Wales has continually voted in Labour MPs with mainly left or center-left policies, for example, supporting the abolishment of prescription charges within the NHS in 2007. Today, the controversial movement for Welsh independence, or at least greater powers for the Welsh government, has been quietly growing, particularly among the youth.