Unlike the Fall of Rome or the Conquest of the Conquistadors, there is no single event that can be used to mark the fall of Ancient Greece. While there were plenty of events that resulted in fire and destruction, there was no dramatic collapse. Instead, the slow decline of Classical Greece is a complex story, with no clear ending. This article covers the main events that led to ancient Greece’s decline in importance and influence, but also its survival.

Crushed by the Macedonians?

Many books on ancient Greece choose to end at a specific time and place: the battlefield of Chaeronea in August 338 BCE. In one day, the Macedonian armies of Philip II crushed the Athenians and Thebans. This effectively ended the independence of Classical Greece, and Philip’s son, Alexander the Great, went on to create a new Hellenistic world. However, while the Macedonians went on to dominate Greece, they never fully conquered or destroyed it.

The other issue with this story is that much of what we associate with ancient Greece—its art, literature, philosophy, and, indeed, the conquests of Alexander—was all still in the future. We often focus on Classical Greece: the glory days of the Athenians and Spartans, the Persian Wars, Thucydides, Pericles, the Parthenon, and the age of the great Greek city-state, the polis. However, the defeat of the polis by the Macedonian monarchy did not mark the end of it.

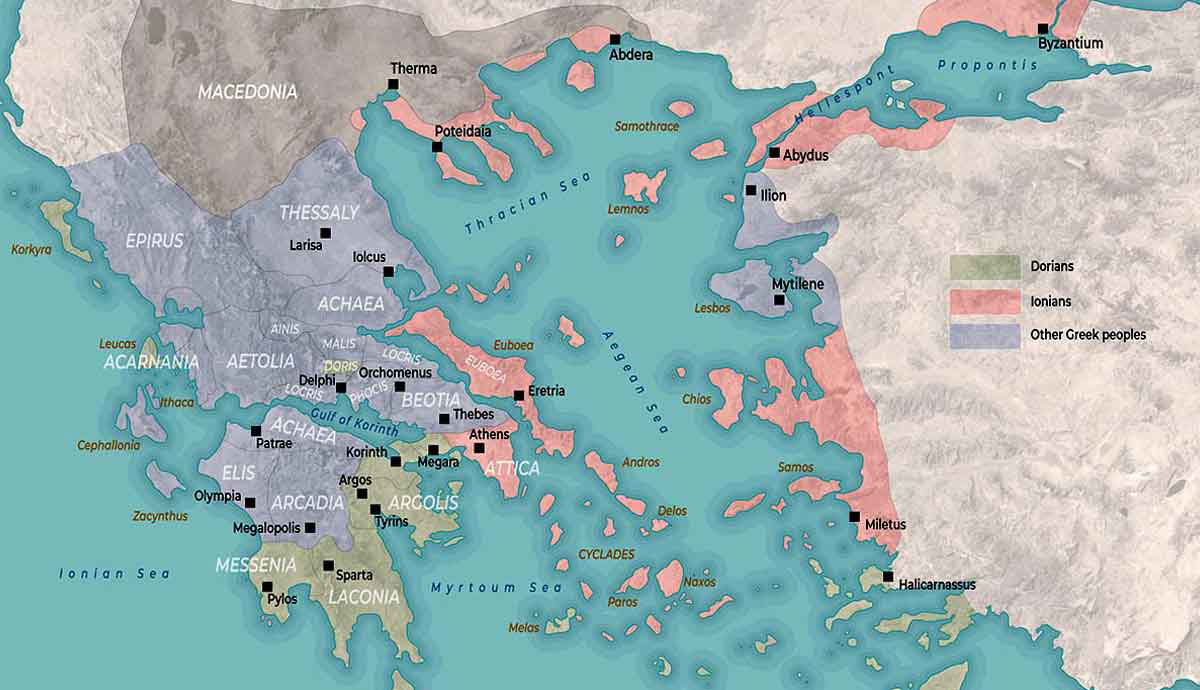

Between 338 and 167 BCE, the Macedonians were by far the single largest and richest state in Greece, but they never controlled the entire country, let alone all the Greek cities scattered across the Mediterranean. Even though no single Greek state was strong enough to resist Macedonia, they never gave up trying. The Thebans soon saw their polis destroyed, but the Athenians and Spartans frequently revolted against the Macedonians. Whenever they could, the Athenians even restored their beloved democracy. Political innovations continued to emerge in the form of multi-poleis federal states such as the Achaians and Aitolians, which had some success in contesting Macedonian power. The idea that the world of the free Greek polis died at Chaeronea has been increasingly challenged.

The oddity of viewing 338 BCE as the end of ancient Greece is that its apparent destroyers, Philip and Alexander, are responsible for the great spread of Greek culture. Following Alexander’s conquests, a Greek ruling elite carved out vast kingdoms across the Middle East and North Africa. While these eventually withered and fell, they transformed the Greek language and culture from the practice of a small, scattered people into a cultural legacy that endured for millennia.

Conquered by the Romans?

The ancient Greek world, both its Aegean core and its Hellenistic kingdoms, was ultimately conquered by the Romans. However, as with the Macedonian conquest, ancient Greece still had a lot of life left in it.

The Romans gradually absorbed the Greek world between the 3rd and 1st centuries BCE. The cities of southern Italy and Sicily were among the first to come under Roman rule. By the 220s BCE, the Romans were getting entangled in the complicated politics and rivalries of Hellenistic Greece. It was the Romans who ultimately resolved the long-standing conflict between the Greek poleis and the Macedonians. The three Macedonian Wars culminated in the Roman triumph at Pydna in 168 BCE and the subsequent dismemberment of the Macedonian Empire.

Several Greek states initially allied with the Romans against the Macedonians, but were eventually forced to submit to Roman hegemony or face destruction. The Roman conquest of Greece is often dated to 146 BCE, when the Romans defeated their former allies, the Achaean League, and destroyed the ancient city of Corinth.

The Roman destruction of Corinth demonstrated their brutality. Whenever the opportunity arose, the Romans enthusiastically plundered the art and wealth held in Greece. Even when direct confrontation with Rome was avoided, the Greeks were frequently humiliated as power shifted to Italy, meaning ambassadors and hostages lined up to travel to the new center of the world. A faithful Roman ally might, within a few years, find itself in Rome’s crosshairs through little fault of its own. When the Romans fought their civil wars in the 1st century BCE, Greece was often the battleground, with the final acts unfolding in the last of the Hellenistic kingdoms: Ptolemaic Egypt.

Aside from the looting and destruction, the arrival of the Romans had further negative effects on Greece. Federal states were broken up and remade in a form compatible with Roman interests. While the political life of the polis continued, Roman influence increased the power of the wealthy elite in Greek cities, tilting the balance away from democracy and towards oligarchy (Chaniotis 2018, 282). However, cities like Athens and Sparta leveraged their past to become hubs of Roman tourism, and the Romans greatly valued Greek culture.

Civilizing the Conqueror

The Roman arrival in Greece was certainly a conquest with all that entails in terms of destruction, dispossession, enslavement, and humiliation. At the same time, Greek culture had long been influential in Rome, and its influence continued to grow over the centuries.

The 1st century BCE Latin poet Horace famously said that Greece’s cultural influence was such that “Captive Greece captured her rude conqueror” (Horace, Epistles 2.1.156). Greek art, philosophy, and literature had a profound influence on Rome, whose elite often spoke Greek. While it was common for Romans to learn Greek, there appears to have been little interest from the Greeks in learning the language of their conquerors (Freeman 2023, 24). Greek remained the lingua franca of the eastern Mediterranean throughout the Roman era.

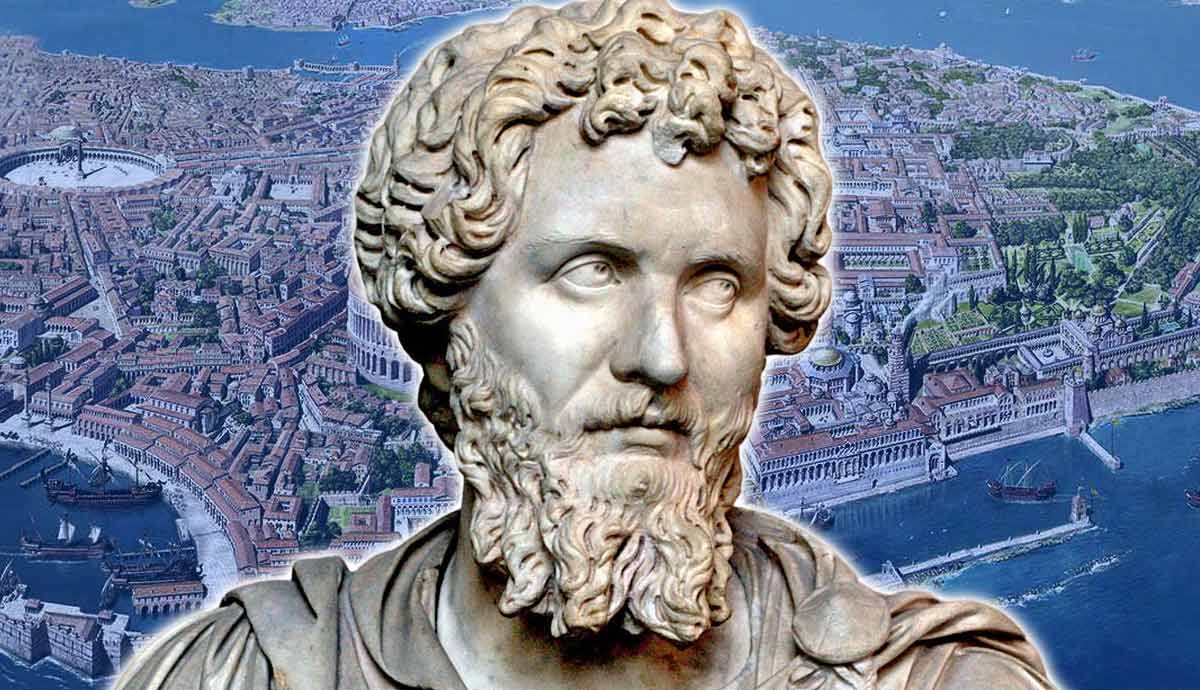

While the first Roman conquerors on occasion toured the sights of Greece, plundering artworks along the way, later generals and emperors were more beneficial. Cicero, Tiberius, Nero, and Hadrian all spent time in Greece with a positive impact. Hadrian was especially fond of Greek culture and restored numerous sites. The attention lavished on Athens is still evident, as several of the city’s surviving monuments date back to the reign of Hadrian.

Not only did Greek culture survive under Rome, but it can even be said to have revived. Much of the surviving body of Greek literature was written under the Romans. Polybius, Strabo, Plutarch, Pausanias, and Arrian are fundamental to our knowledge of ancient Greece. The influence of the 2nd-century CE Greek doctor Galen lasted for centuries. Plutarch is a particularly interesting example. A member of the local Boiotian Greek elite in the 1st century CE, he participated in the political and religious life of central Greece as members of his class had done for centuries, whilst writing a vast amount. Crucially, Plutarch wrote parallel lives of prominent Greeks and Romans, which compared key figures from both societies. Surviving largely intact, they are now fundamental historical sources.

Greek and Roman culture flourished because, following the civil wars of the 1st century BCE, there was a prolonged period of peace, which left Greece and the Aegean relatively untroubled for centuries. However, Greece’s fate was now linked to Rome’s, and when large-scale invasions started to make headway into Roman territory, Greece was vulnerable. The Heruli raids into the Balkans in 267 CE caused extensive damage in Greece, particularly in Athens. The events of 267 CE left a lasting mark on many of Greece’s archaeological sites as the remaining physical links to ancient Greece came under threat.

Abolished by the Christians?

The dominance of Greek culture in the eastern Mediterranean influenced Roman culture, aiding the growth of Christianity. While this new religion was infused with the Greek culture of its day, it also eroded the beliefs that created that culture and contributed to its final decline. As Christianity gained more converts, its saints and martyrs gradually displaced the cults of local gods and heroes that had long formed the basis of Greek religion and identity (Pont 2024, 761). Christianity’s rise saw many temples attacked, converted, or fall out of use, while animal sacrifices were banned in 341 CE. At its worst, this process resulted in conflict, such as the murder of the female philosopher Hypatia of Alexandria by Christians in 415 CE.

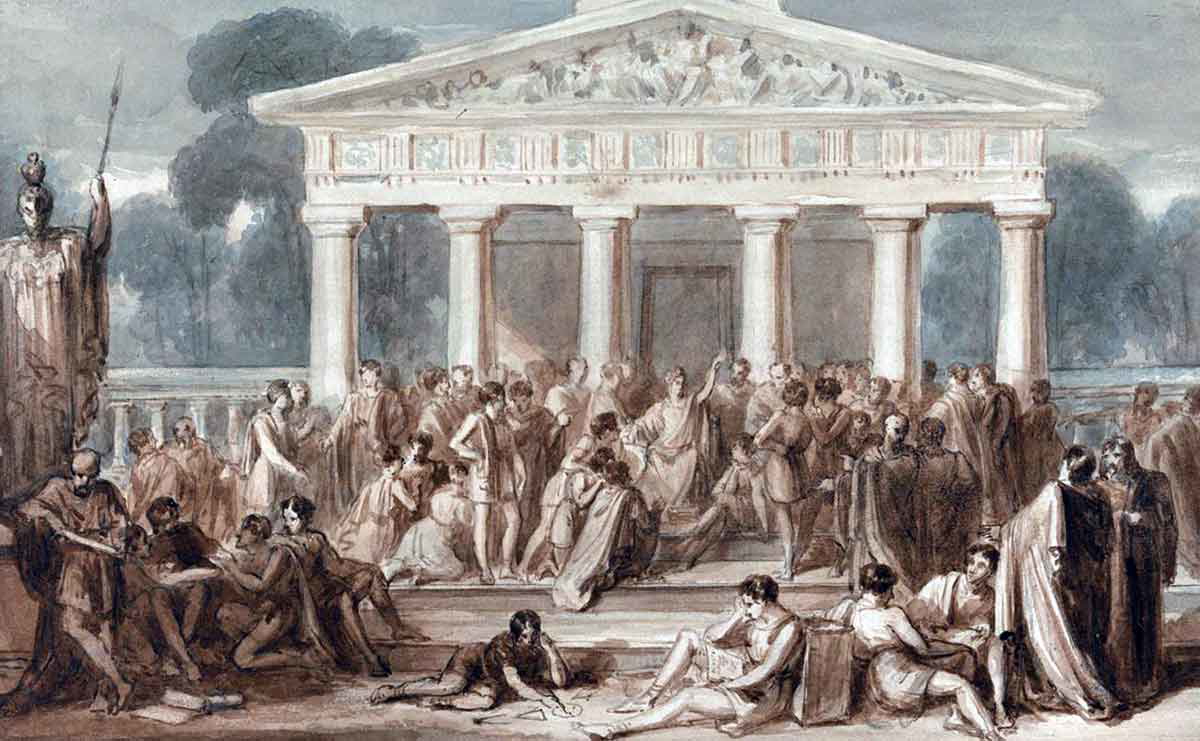

Once Christianity gained followers in the imperial court, many aspects of ancient Greek culture came under unsustainable pressure. Shifts in religious beliefs have been seen as factors in the end of the Olympic Games, at the end of the 4th century CE, and the decline of the philosophical schools of Athens in the 6th century CE (Remijsen 2015).

Changes in the administration of the Empire further advanced this process. The need to defend against increasing raids furthered the rise of local elite individuals who could provide leadership, thereby undermining the collective administration of the polis. Administrative reforms weakened local governments and limited civic resources (Pont 2024, 756). By the 4th century CE, local magistrates and law courts were being supplanted by bishops and the Church (Pont 2024, 761). As a result, the recognizable Greek city-state did not survive the changes of Late Antiquity.

The End of Ancient Greece

As antiquity transitioned into the Middle Ages in the 6th century CE, ancient Greece had come to a definitive end. The culture of the polis, including its gods and rituals, was no longer a major part of society. And yet, the conqueror of the Greeks, the Roman Empire, continued in a very Greek-influenced form. For another thousand years, the Eastern Roman Empire was Greek-speaking, its capital, Constantinople, was adorned with Classical art, and its libraries and literate elite preserved and cherished ancient works.

The decentralized nature of ancient Greek society meant that its end came not in a single dramatic moment but instead gradually. The cherished freedom of the Greek polis was curtailed but never extinguished by the Macedonians. Macedonian expansion and Hellenization meant that by the time Greek political freedom was ended by the Romans, Greek culture was widespread and deeply embedded across much of the eastern Mediterranean. Greek culture was celebrated, and aspects of it were adopted by the Romans, who spread Greek ideas across their Empire. Greek culture influenced emerging Christianity, but its widespread adoption across the Empire eventually undermined the pinnacles of ancient Greek culture.

In the nearly 2,000-year lifespan of ancient Greece, the arrival of the Romans was clearly a turning point. Having defeated the Persians and resisted the Macedonians, it is worth wondering why the Greeks fell to the Romans. When considering this question in a famous 1990 article, Runciman compared Rome, which was after all just another city-state, to the Greek polis (Runciman 1990, 357). He suggested that the Romans were better at concentrating power and opening their citizenship to outsiders, meaning that with every conquest, they acquired more citizens and more manpower. The polis, with its democratic ideals and commitment to autonomy, could not compete. But it was also the decentralized nature of the Greek world that made it resilient and allowed its culture to flourish following conquest.

Select Bibliography

Chaniotis, A. (2018). The Age of Conquests: The Greek World from Alexander to Hadrian. Harvard University Press.

Freeman, C. (2023). The Children of Athena: Greek writers and thinkers in the Age of Rome, 150 BC–AD 400. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pont, A.-V. (2024). “Epilogue: The End of Polis Culture,” in Hallmannsecker, M. and Heller, A. The Oxford Handbook of Greek Cities in the Roman Empire. 751-766. Oxford University Press.

Remijsen, S. (2015). The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity. Cambridge University Press.

Runciman, W.G. (1990). “Doomed to Extinction: The Polis as an Evolutionary Dead-End,” in Murray, O. and Price, S. (eds). The Greek City: From Homer to Alexander. 347-368. Clarendon Press.