The Illyrians were a mosaic of tribes spread across the western Balkans, a region defined by dramatic coastlines, mountain strongholds, and cultural complexity. From their earliest traces in the Bronze Age to assimilation into the Roman Empire, the Illyrians remained a distinct presence on the periphery of the classical Mediterranean. Although Roman writings often labeled them as pirates and barbarians, they were far more than mere raiders of the Adriatic. Independent, organized, and strategically positioned, the Illyrians repeatedly drew the attention and unease of Rome. But why did Romans fear them so much?

Origins & Geographic Scope of the Illyrians

The question of the origin of the Illyrians is still not fully resolved. The Illyrians are generally considered part of the Indo-European linguistic and cultural family, which would mean that they settled in the western Balkans from northern Europe sometime in the 2nd millennium BCE. However, there are also theories suggesting that the Illyrians were actually descendants of the prehistoric local population that had lived in this area since the Neolithic period.

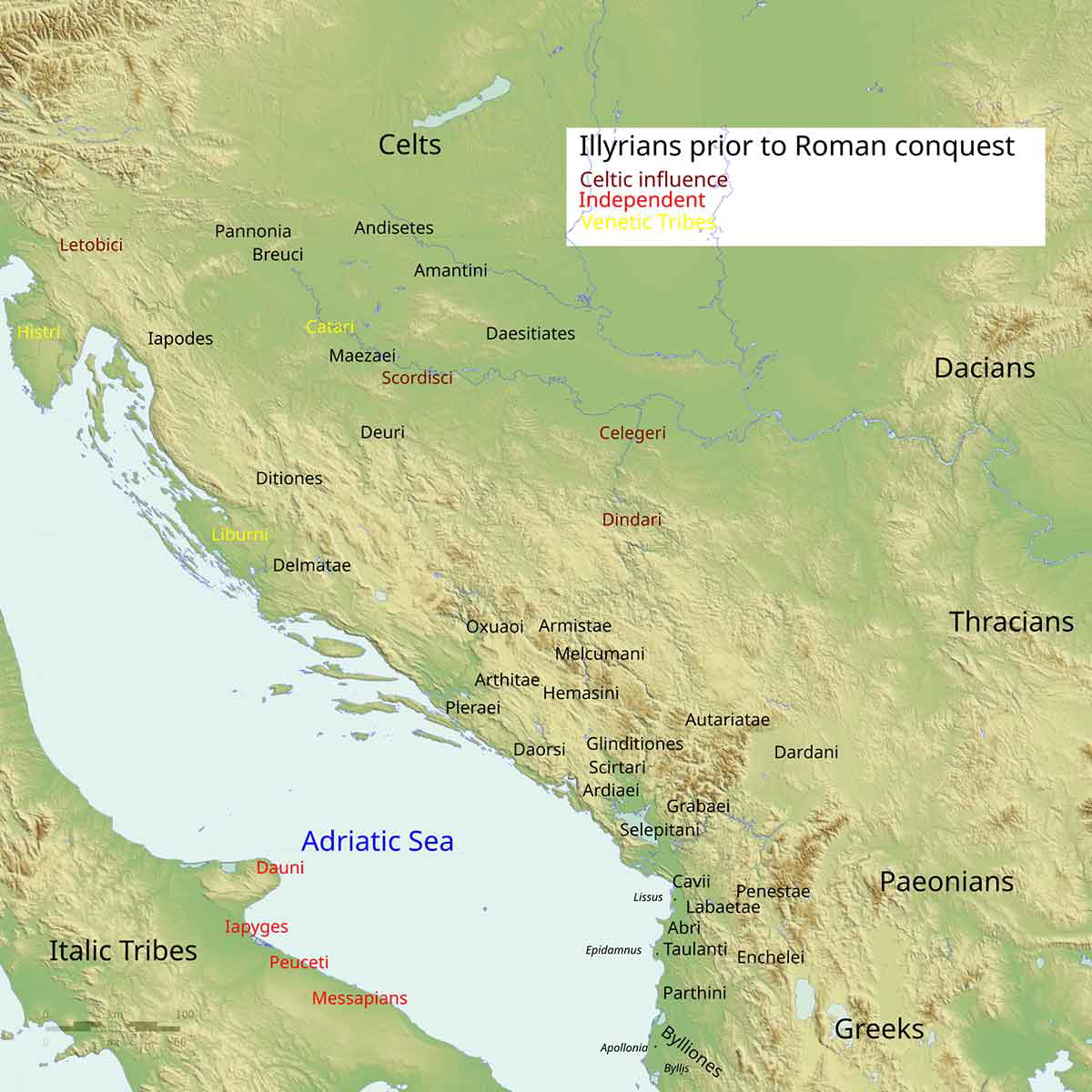

Geographically, the Illyrians occupied the area from the Adriatic Sea in the west to the Morava and Vardar rivers in the east, from the Julian Alps in the north to Epirus in the south. This area was highly diverse, including numerous mountainous elevations, fertile valleys, and a vast coastline. This very diversity, along with their deep knowledge of the terrain, helped the Illyrians resist foreign invasions for a long time. This area includes the territories of present-day Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Albania, as well as parts of Slovenia, Serbia, and North Macedonia.

There is no evidence that the Illyrians actually called themselves by that name. It was most likely an exonym that originally emerged in ancient Greece and was later adopted by the Romans. The Illyrians referred to themselves as Dalmatae, Dardanians, Liburnians, Autariatae, Pannonians, and by other tribal names. Therefore, we can speak of the Illyrians only as a geo-cultural zone, not as a single, cohesive nation.

How the Illyrians Entered the Greek Chronicles & Clashed With Macedon

The first detailed military-political account of the Illyrians is given by Thucydides in his “History of the Peloponnesian War.” Around 423 BCE, King Perdiccas II of Macedon formed a military alliance with the Spartan general Brasidas and the Illyrians, who were supposed to help him fight Arrhabaeus of Lynkestis. However, when the time for battle at Lynkestis came, the Illyrians turned against their allies and joined their enemy. The Macedonian army fled under the fierce assault of the Illyrian warriors, leaving Brasidas alone, who then withdrew silently.

Under the rule of Philip II, Macedonia expanded into parts of Illyria. At the Battle of Erigon Valley in 358 BCE, a decisive clash occurred between Philip II and the Illyrian king Bardylis, who ruled the Dardanian tribe. Bardylis suffered a crushing defeat, and according to Diodorus Siculus, over 7,000 Illyrian soldiers were killed.

When Alexander the Great succeeded Philip II, the Illyrians saw it as an opportunity to free themselves from Macedonian rule. In one of the earliest campaigns of his career, Alexander set out with 23,000 soldiers to invade Pelium, which was held by Cleitus, the son of Bardylis. Cleitus was soon reinforced by Glaukias, the king of the Taulantii tribe. For a short time, Alexander was surrounded by enemies, but during the night, he managed to slip behind their lines and launch a counterattack. After defeating the Illyrian army, he stormed Pelium and burned it to the ground.

The Rise of Illyrian Sea Power Under Agron & Teuta

By the end of the century, the Ardiaei had emerged as the most powerful of the Illyrian tribes. King Agron completely transformed the naval forces and began to dominate parts of the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. The ships used by the Illyrians during this period were light and agile galleys, ideal for quick attacks and even quicker retreats. These galleys were called liburnas, named after the Liburnian tribe, and they were later incorporated into the Roman fleet as a standard part of their navy.

When the island city of Medion in Acarnania came under siege by the Aetolian League in 231 BCE, the Acarnanians called upon Agron for help. Agron sent a massive fleet that achieved a decisive victory and lifted the siege of Medion. It is recorded that he celebrated the victory for several days and ultimately died from excessive alcohol consumption.

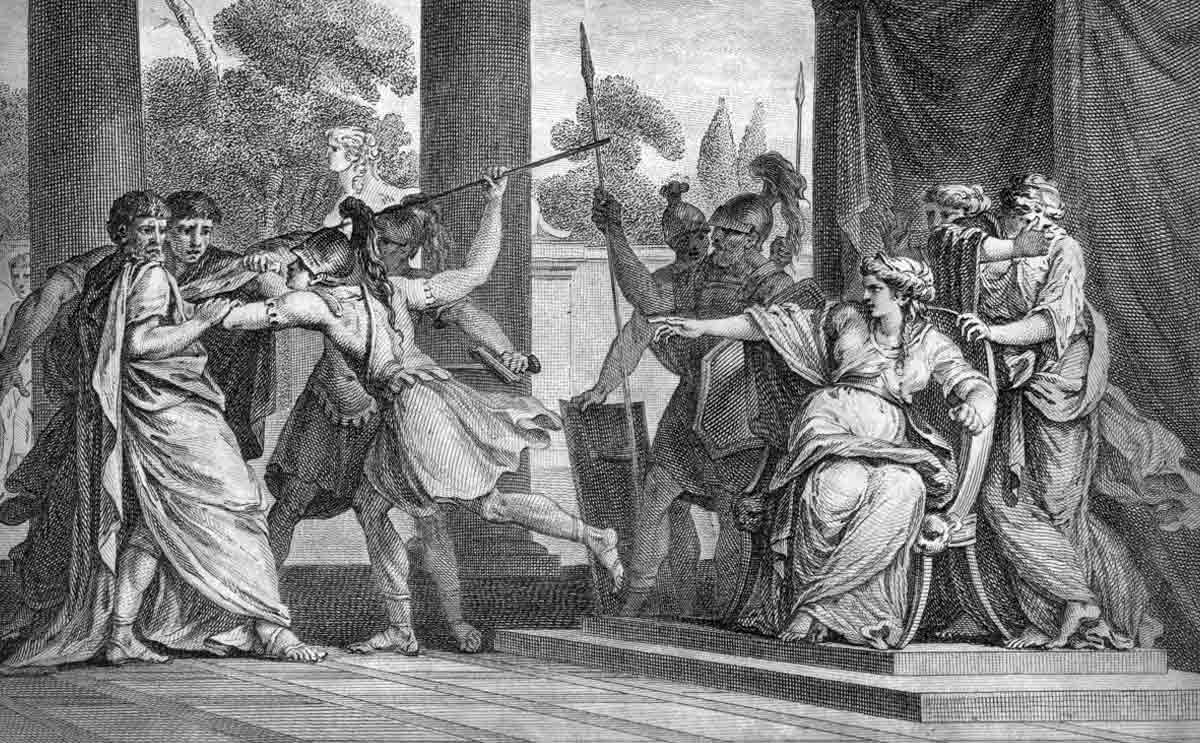

Agron was formally succeeded by his underage son Pinnes, but in reality, the new ruler became his widow, Queen Teuta, who took Illyrian piracy to an even more dramatic level. Illyrian pirates attacked Greek cities, Roman merchant ships, and coastal settlements. These provocations attracted the unwanted attention of Rome, which sent envoys to Teuta in an attempt to negotiate better relations. After the negotiations failed, one of the envoys was killed, leading to the beginning of a series of conflicts known as the Illyrian Wars.

The Illyrian Wars & the End of Coastal Sovereignty

The First Illyrian War began in 229 BCE, triggered by Illyrians killing a Roman envoy. Rome responded by sending 200 warships, 20,000 infantry, and 2,000 cavalry, led by consuls Gnaeus Fulvius Centumalus and Lucius Postumius Albinus. Rome also had the support of the Greek city of Corcyra, which had previously been besieged by the Illyrians.

Demetrius of Pharos, a prominent Illyrian leader who was formerly allied with Teuta, switched allegiance to the Roman Republic in exchange for being allowed to continue ruling over Pharos. This betrayal shattered Teuta’s power and allowed the Romans to directly strike her ports. Realizing she could not win the war, Teuta soon negotiated peace with Rome. Her rule was reduced to a small portion of inland territory.

Demetrius of Pharos proved to be a highly capable and cunning politician. He began expanding his influence and territory into areas that had once been under Teuta’s control. Demetrius’s ambition was to create a new Illyrian kingdom. Rome was dealing with the rising threat of Hannibal in the west and could not afford any incidents on the opposite front. As a result, in 219 BCE, the Senate dispatched a fleet led by the consul Lucius Aemilius Paullus to seize all of Demetrius’s strongholds. After a seven-day siege, they successfully captured the important city of Dimale, from which they moved directly toward Pharos. In the decisive battle at Pharos, the Romans emerged victorious. Demetrius himself managed to escape to Philip V of Macedon, where he became his close advisor.

Unlike the first two Illyrian wars, the Third Illyrian War did not begin because of piracy. The last Illyrian king, Gentius, leader of the Ardiaean tribe, provoked Roman fear through his aggressive diplomacy and military buildup. For the Romans, the timing was unfortunate. They were already deeply engaged in the Third Macedonian War, and King Gentius had formed a military alliance with the Macedonians.

Gentius deliberately sought conflict, believing he would receive strong support from Perseus of Macedon. The Roman Senate sent Lucius Anicius Gallus with 30,000 soldiers, who advanced quickly toward Gentius’s capital, Scodra. Gentius had an army of 15,000 men and hoped for military assistance from Macedonia. After a seven-day siege of Scodra, realizing that no help was coming, Gentius decided to surrender. He was paraded in a Roman triumph and likely died in prison in Spoletium.

Century-Long Fight Between Rome and the Dalmatae

After the Third Illyrian War, the entire homeland of the Illyrians came under the supervision of Roman legates and prefects. Due to the resistance of the Illyrian peoples, it took more than a century to create the conditions necessary for the establishment of a province. The fiercest in their resistance were the Dalmatae, who lived in the area of modern-day Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The First Roman-Dalmatian War began in 156 BCE, when the Dalmatae captured the city of Promona, which was under Roman control. The Senate first sent Gaius Marcius Figulus, who was unable to manage in the Illyrian terrain. Only in the following year did Scipio Nasica, with a much larger army, succeed in forcing the Dalmatae to surrender.

This victory only temporarily halted the Dalmatae. In 119 BCE, they once again attacked cities under Roman protection. This time, the Senate sent Lucius Caecilius Metellus to Delminium, the capital of the Dalmatae. After a narrow victory, Metellus was awarded the honorary title “Delmaticus.”

Even after this defeat, the Dalmatae did not submit to Rome. Between 78 and 76 BCE, Gaius Cosconius led a new campaign, during which he burned the important Illyrian city of Salona, pushing the Dalmatae into the mountainous regions.

When Augustus took power in Rome, the Dalmatae were still defiant. He launched a decisive campaign against the Dalmatae in 34 BCE with a large number of Roman legions. In just one year, he managed to capture the important cities of Promona, Setovia, and Andetrium, from which he was able to cut off supply routes to the remaining Illyrian fortresses and force them to surrender. After his campaign, the Illyrians were completely subdued by Rome, and the province of Illyricum was established.

The Uprising That Made Rome Bleed in the Balkans

High Roman taxation and forced conscription caused widespread dissatisfaction among the Illyrian population. In the year 6 CE, Rome began the forced mobilization of Illyrians to participate in an invasion of Germania. The Illyrians felt exploited and did not want to fight in distant lands. This event became the trigger for the Great Illyrian Revolt, which the Romans were barely able to suppress.

The Romans called this revolt the Bellum Batonianum (War of the Batos) because the Illyrians were led by two leaders named Bato: Bato of the Daesitiates and Bato of the Breuci. They managed to rally nearly all of Illyricum, especially Dalmatia and Pannonia. In a sudden and coordinated uprising, the Illyrians attacked Roman outposts throughout Illyricum. The rest of the Roman army had to abandon the Germanic campaign and rush to respond.

The Illyrians avoided open battles, knowing that they would be defeated by the powerful Roman legions led by the famous general Tiberius. Instead, their tactics consisted of mountain ambushes and surprise night attacks. This approach proved effective, and soon they were in control of a large part of the province.

Tiberius divided his legions, sending one group to Pannonia to isolate Bato of the Breuci, and the other into the mountainous regions of Dalmatia. Bato of the Breuci surrendered to Tiberius in an attempt to save his tribe; an act that cost him his life. Now, Bato of the Daesitiates stood alone against the powerful Roman legions. Tiberius laid siege to Andetrium, the capital of the Daesitiates. After a long, exhausting siege, Bato of the Daesitiates personally surrendered to Tiberius.

When Tiberius asked him why he had started the revolt, Bato replied: “You Romans are to blame for this; for you send as guardians of your flocks, not dogs or shepherds, but wolves.” Cassius Dio, Roman History, 56.16

Romanization and Rise of Illyrian Emperors

After Bato’s uprising, the province of Illyricum was divided into two provinces: Pannonia and Dalmatia. New cities sprang up rapidly, and the Illyrians gradually adopted the Roman language and culture. The process of Romanization progressed smoothly, so much so that a large number of Roman emperors in the 3rd and 4th centuries CE had Illyrian roots. The first major Illyrian emperor was Claudius Gothicus (268-270 CE). He was originally from Sirmium, near present-day Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia, and is known for stopping a major Gothic invasion at the Battle of Naissus.

Aurelian (270-275 CE) was the next significant emperor of Illyrian origin. He reunified the Roman Empire, which had at that time fractured into the Gallic Empire in the West and the Palmyrene Empire in the East. For this achievement, he was awarded the title “Restitutor Orbis” (Restorer of the World). He also built the monumental Aurelian Walls around Rome, which stood for centuries.

Perhaps the most important Roman emperor of Illyrian origin was Diocletian (284-305 CE) from Salona. Diocletian established the Tetrarchy, a political system with four rulers. He reformed the army, the tax system, and the administration, thus ending the Crisis of the Third Century that had shaken Roman power.

Constantine the Great (306-337 CE) was the last major emperor of Illyrian origin. Unlike Diocletian, who is remembered for his persecution of Christians, Constantine legalized Christianity with the Edict of Milan. He also brought an end to the Tetrarchy and established himself as the sole ruler of the Roman Empire.