More than an art movement, Surrealism was an attitude, a quest for freedom that encompassed all aspects of life; just like their male colleagues, female Surrealist artists were also political activists, women’s rights advocates, and revolutionary fighters. They lived extraordinary lives as free individuals inventing their own beauty and dignity, expressing their unmediated energy, sexuality, and humor. As Meret Oppenheim said, female Surrealist artists lived and created guided by “a conscious desire to be free.”

Female Surrealist Artists and Women’s Emancipation

When on August 21st, 1933, eighteen years one Violette Nozière confessed to her father’s poisoning, the French press exploded in outrage against her.

According to the public opinion, Violette was “not a serious girl,” showing tendencies typical of newly “emancipated” women: working jobs, earning money, and living dissolute lives incompatible with their working-class peers. It did not matter whether the sexual abuse allegations against her father were true once the press had decided to make an example out of her.

A lone voice of dissent, the Surrealists showed their support with a collective oeuvre electing Violette as their Black Angel, the muse that would inspire their continuous fight against the bourgeois mentality and its myths of law and order, logic and reason. The system that led to the social inequity of the post-industrial era and to the horror of the First World War was, according to Surrealists, irredeemably flawed. Not just a political revolution, but a cultural one was needed to defeat it.

Thus, women’s emancipation was fundamental to the dismantling of capitalism and patriarchy, starting with the challenging of the bourgeois perception of women as inherently good, selfless, submissive, ignorant, pious, and obedient.

Poetry. Freedom. Love. Revolution. Surrealism was not bizarre escapism but expanded awareness. The lack of boundaries and censorship provided a safe place to discuss and process WWI’s collective trauma while also providing an outlet for women’s creative needs.

While they were welcomed and actively participated in the movement, the Surrealist’s understanding of women was still very much rooted in stereotypes in idealizations. Women were either seen as muses, as objects of inspiration or admired as infantilized figures gifted with vivid imagination thanks to their naivety and hysteria’s predisposition.

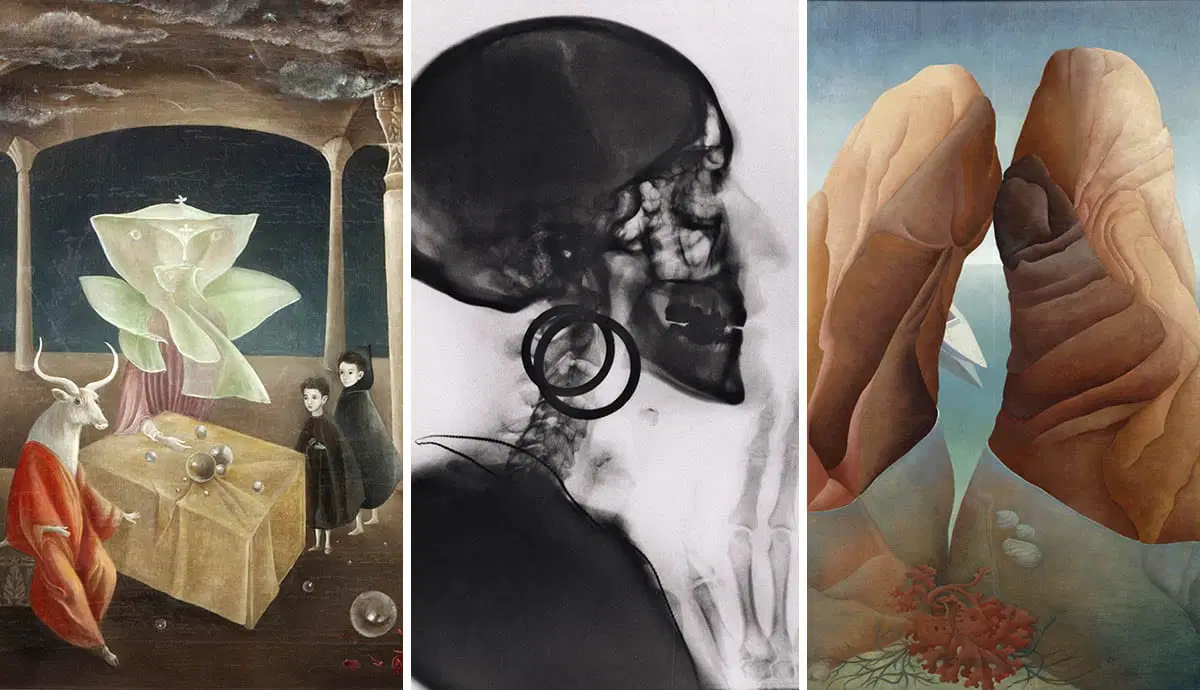

It was through the work of female Surrealist artists that women’s identity truly had a chance to flourish and become three-dimensional, as they appropriated the myth of the muse to express their full potential as active creators.

For the longest time, female artists had mostly been remembered in terms of their relationships, often sentimental, with male artists. Only in recent times has their work had been analyzed independently and given the attention it deserves. Here are seven among the most well known and studied women Surrealists, hoping that many others will eventually be “rediscovered” and finally written into art’s official records.

First Generation Female Surrealist Artists

Valentine Hugo

Born in 1887, Valentine Hugo was an academically trained painter having attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Growing up in an enlightened and progressive household, she followed in her father’s footsteps in becoming an illustrator and sketcher. Known for her work with the Russian ballet, she built a lasting professional connection with Jean Cocteau. Through Cocteau, Hugo met her future husband, Jean Hugo, great-grandson of Victor Hugo, and André Breton, the founder of the Surrealist movement, in 1917.

Through this friendship, she grew more and more connected to the newly formed group of artists, which now included Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, Pablo Picasso, and Salvador Dalí. During this time, she joined the Bureau of Surrealist Research and exhibited her works at the Surrealist Salons in 1933 and at the exhibition “Fantastic art, Dada, Surrealism” at MoMA in 1936.

Afflicted by fellow Surrealist René Crevel’s suicide and by the departure of Tristan Tzara and Eluard, she abandoned the Surrealist group for good. In 1943, her word was included in Peggy Guggenheim’s Exhibition of 31 Women. Her first retrospective exhibition was held in Troyes, France, in 1977, ten years after her death.

Meret Oppenheim

The daughter of a German Jewish father and a Swiss mother, Meret Oppenheim was born in Berlin in 1913 but moved to Switzerland at the outbreak of WWI.

Raised in a culturally flourishing household, both her mother and grandmother had been suffragettes. Her grandmother was one of the first women to study painting and the Düsseldorf Academy. At her house in Carona, Meret would meet many intellectuals and artists, such as Dadaist artists Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings, as well as writer Herman Hesse who briefly married her aunt.

Her father, a physician, was a close friend of Carl Jung and often attended his lectures: he introduced Meret to analytical psychology and encouraged her to keep a dream journal from an early age.

Because of this knowledge, Meret Oppenheim was arguably the only Surrealist with authority on psychoanalysis. Curiously, she was also one of the few Surrealists who favored Jung over Freud.

In 1932, she moved to Paris to pursue her artistic career, coming in contact with Surrealism through the Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti. She soon befriended the rest of the group, which at the time included Man Ray, Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Dalí, Ernst, and René Magritte.

Seated at a Parisian cafe with Picasso and Dora Maar in 1936, Picasso noted the peculiar fur-lined bracelet, designed for Elsa Schiaparelli’s house, on Oppenheim’s wrist. In an explicit version of the events, Picasso commented on how many of the things he enjoyed could be improved with a little fur, to which Oppenheim replied “Even this cup and saucer?”

The result of this playful banter was Oppenheim’s most famous Surrealist object, Déjeuner en Fourrure also known as Fur-lined cup or simply Object. Included in Breton’s “First exhibition of Surrealist Objects”, the piece was bought by Alfred Barr for the newly established MoMA: considered the “quintessential Surrealist object,” Fur-lined cup became the first work by a female artist in the museum’s permanent collection.

While her work was received enthusiastically by her male colleagues, she still struggled to establish herself as an artist in her own merit and to escape the role of muse and object of inspiration.

Her independent nature, her disinhibition and rebellious attitude, made her, to the male colleagues’ eyes, the fetishized embodiment of the femme-enfant.

This dismissive attitude is evident in Ernst’s comment on the exhibition of Objet: “who covers a soup spoon with luxurious fur? Little Méret. Who has outgrown us? Little Méret.” These identity struggles, the consequences of anti-semitism on her father’s practice, and the Surrealist diaspora during WWII, compelled her to move back to Switzerland. Here she fell into a deep depression and disappeared from the public eye for almost twenty years.

Active throughout the 1960s and 1970s, she eventually distanced herself from the movement, rejecting the references made to Surrealism since Breton’s era. Sympathetic to Feminism, she however never betrayed her Jungian belief that no difference exists between men and women, firmly refusing to participate in “female only” exhibitions.

Her life-long mission seams to have been the shuttering of gender conventions and stereotypes by surpassing sex divisions altogether and reclaiming total freedom of expression. “Women are not goddesses, nor fairies, nor sphinxes,” she said, “those are the projections of men.” “To prove via one’s lifestyle that one no longer regards as valid the taboos that have been used to keep women in a state of subjugation for thousands of years” is the task of female artists. Because “freedom is not given” she reminds us, “one has to take it.”

Valentine Penrose

One of the most critical and irreverent female Surrealist artists, Valentine Penrose devoted most of her life to the dismantling of the bourgeois perception of women as inherently good, selfless, husband-worshipping, submissive, ignorant, pious, hardworking, obedient wife and daughters.

One of the earliest women to join the movement, Penrose was fascinated with examples of unorthodox women and lived an unconventional life herself.

Born in 1978 as Valentine Boué, she married historian and poet Roland Penrose in 1925 adopting his name. Along with her husband, she moved to Spain in 1936 to join the worker militia in defense of the revolution.

Her interest in mysticism and Eastern philosophies brought her to India numerous times, where she studied Sanskrit and Eastern philosophies. She was particularly interested in tantrism, in which she identified a valuable alternative to the Surrealist obsession with “genital” sexuality influenced by Freud’s psychoanalysis.

She believed that the Surrealist view of women as a necessary “other half”, ultimately failed to emancipate women from their bourgeois roles and impaired them from finding an independent path. Her growing interest in Occultism and Esotericism, eventually drew a wedge between her and her husband, leading to divorce in 1935.

The following year she traveled to India with her friend and lover Alice Paalen. While two women never saw each other again after the trip, lesbianism became a recurring topic in Penrose’s oeuvre, often centered around Emilie and Rubia characters.

Her 1951 collage novel Gifts of the feminine is considered the archetypical Surrealist book. Recounting the adventures of the two lovers traveling across fantastical worlds, the book is a fragmented collection of bilingual poetry and juxtaposed collages, organized without continuity and with an increased level of complexity.

Always challenging the stereotype of the ideal woman, in 1962, she published her most famous work, the romanticized biography of serial killer Elizabeth Bathory, the “Bloody Countess”. The novel narrating the story of a lesbian gothic monster required a year of research across France, Great Britain, Hungary, and Austria.

Having always remained closed to her ex-husband, she spent her last years living at his Farley Farm House, along with his second wife, American photographer Lee Miller, also known as Lady Penrose.

Claude Cahun

Claude Cahun was born Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob in Nantes in 1894. Also a daughter of a Jewish father, a working-class member, and a lesbian, Claude Cahun created many different personae to escape discrimination and prejudice, starting from choosing a pseudonym, a gender-neutral name she adopted for most of her life.

Cahun is an emblematic example of an artist that while remained almost unknown during her time, gained popularity and recognition in recent years, remaining one of the most well known among female Surrealist artists. Often considered a precursor to post-modern feminist art, her gender-bending art and the expanded definition of femininity that she put forth became a fundamental precedent in the post-modernist discourse and second-wave Feminism.

Cahun came in contact with the Surrealists through the AEAR, the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she met Breton in 1931. In the following years, she regularly exhibited with the group: her famous photo of Sheila Legge standing in Trafalgar Square appeared in numerous magazines and publications.

A member of both Surrealism and French communist groups, as a lesbian, Cahun didn’t receive much solidarity from either of them. Despite the revolutionary attitude, communists considered homosexuality a luxury only the dissolute elite could afford. Breton, on the other hand, never fully accepted it except for the few tantalizing lesbian images intended for male entertainment.

She lived with her step-sister and lifelong partner Suzanne Malherbe, who also adopted the male pseudonym of Marcel Moore. Wage disparity made it intentionally impossible for women to be self-sufficient, so they had to rely on Cahun’s father’s economic support for survival.

Lacking an external audience, Cahun’s art was mostly created within her and Marcel’s domestic sphere, providing an unfiltered glimpse into their artistic experimentations. Through the use of masks and mirrors, Cahun reflected on the nature of identity and its plurality, setting a precedent for post-modernist artists like Cindy Sherman.

With her photos, Cahun rejected and surpassed the Modernist (and Surrealist) myths of the essential femininity and the ideal woman, putting forth the post-modern idea that gender and sexuality are, in fact, constructed and performed, and that reality is not merely known through experience but mediated and defined through discourse.

During the German invasion, Claude and Marcel were arrested for their anti-fascist efforts and sentenced to death. Although they survived until liberation day, Claude’s health never fully recovered, eventually dying at the age of sixty in 1954. Marcel survived her till 1972 when she committed suicide.

Toyen

Born Marie Čermínová in 1902, Toyen was part of the Czech Surrealism, working close to Surrealist poet Jindřich Štyrský. Like Cahun, Toyen also adopted a gender-neutral pseudonym, probably inspired by the French “citoyen” citizens. A sexually ambiguous character, Toyen entirely disregarded gender conventions wearing both male and female clothing and adopting both gender’s pronouns.

Although skeptical of French Surrealism, Toyen’s art shared many themes with Breton’s movement, and by the 1930s, the artist had become an essential member of the Surrealist. Always transgressive, Toyen’s interest in dark humor and eroticism consolidated the artist within the Surrealist tradition of hypersexualized, irreverent art influenced by the Marquis de Sade’s writings.

In 1909, Apollinaire had found one of De Sade’s rare manuscripts at the Biblioteque National in Paris. Deeply impressed, he described him as “the freest spirit who ever lived” in his essay L’oeuvre du Marquis de Sade, contributing to De Sade’s popularity resurgence among Surrealist artists.

De Sade, from whose name sadism and sadist derive, spent most of his life either incarcerated or committed into mental asylums because of his writing, which combined philosophical discourse with pornography, blasphemy, and sexual fantasies of violence. Heavily censored, his books have nonetheless influenced European intellectual circles for the past three centuries.

Like the Bohemians before them, Surrealists were intrigued by his stories, identifying themselves with De Sade’s revolutionary and provocative persona and admiring his controversial attacks on bourgeois tastefulness and prudery.

Mixing violence and sexual impulse, the sadistic attitude became a means to liberate the innate urges lurking in the unconscious mind: “Sade is surrealist in sadism” announced the First Manifesto of Surrealism. Toyen paid homage to the libertine writer by producing a series of erotic illustrations for Štyrský’s Czech translation of Justine.

Never absent, the political aspect of Toyen’s art became nonetheless more explicit as the political situation in Europe deteriorated: The Shooting Gallery series shows the destructive nature of war through the iconography of children’s games. Having settled in Paris in 1948 following the Communist coup d’ état in Czechoslovak, Toyen remained active until death in 1980, continuing to work alongside poet and anarchist Benjamin Péret, and the Czech painter Jindrich Heisler.

Second-Generation Female Surrealist Artists

Ithell Colquhoun

Separated during World War II, second-generation Surrealists tended to drift away from the core movement, developing their own research areas.

Female artists reappropriated the Surrealist idea of the mythical woman and remolded it into the potent image of the sorceress, a powerful being in control of her transformative and generative powers. The femme-enfant that inspired the first generation of female Surrealist artists had now grown into the femme-sorciere, the master of her own creative power.

While male artists seemed to require an external intermediary, often the female body, as a proxy for their subconscious, female artists didn’t have such barriers, employing their own bodies as the ground for their search. The “self otherness,” the alter ego through which female artists explored their inner self was not the opposite sex, but rather Nature itself, often represented through beasts and fantastical creatures.

As Hille put it, “Surrealists looked with one eye outward and one inward. However, Carrington [and Varo] had both eyes open, looking at both the real and the magical in reality.”

For their generation, who lived through two world wars, economic depression and a failed revolution, magic and primitivism were liberating. For artists, magic was a means for change, uniting and suspending the reams of art and science, a much-needed alternative to religion and positivism that had led to the atrocities of the war. For women, lastly, the occult became a means to subvert patriarchal ideologies and empower the female self.

Born in Shillong, British India, in 1906, Ithel Colquhoun became interested in Occultism at the age of seventeen after reading Crowley’s Abbey of Thelema. Educated at the Slade School of Art, she moved to Paris in 1931. However, it was in Britain that her career actually took off: holding a number of solo exhibitions, by the end of the 1930s, she had become one of the prominent figures of British Surrealism. Her affiliation to the movement was nonetheless short-lived, leaving after only one year when forced to choose between Surrealism and Occultism.

While she continued to define herself as a Surrealist artist, severing formal ties with the movement allowed her to develop a more personal aesthetic and poetic. In Surrealist fashion, she employed many Surrealist techniques such as frottage, decalcomania, collage, while also developing her own inspiration games such as parsemage and entoptic graphomania.

Channeling the dark power of artists such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Colquhoun recognized in women a potential for creation, salvation, and resurrection that linked them with nature and the cosmo.

Her work, drawing parallels between the preservation of nature and women’s emancipation, established a powerful precedent for the later development of Ecofeminism.

The search for the lost goddess represented women’s reconnection with Nature and the rediscovery of their own strength, the journey leading to the reclamation of knowledge and power.

Leonora Carrington

One of the most longevous and prolific female Surrealist artists, Leonora Carrington was a British artist who fled to Mexico during the Surrealist diaspora.

Born in 1917, Leonora Carrington was the daughter of a British wealthy textile manufacturer and an Irish mother. Her rebellious attitude had her expelled from at least two schools. Over twenty years younger than most Surrealists, Carrington came in contact with the movement almost solely through exhibitions and publications.

It was in 1937 that she met Max Ernst at a London party. The two immediately bonded and moved together to Southern France, where he promptly separated from his wife. One of her most famous works, Self-Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) was painted during this time.

With the outbreak of WWII, Ernst was interned as an “undesirable foreigner” but was released thanks to Eluard’s intercession. Arrested again by the Gestapo, he only barely escaped internment camp, which prompted him to seek asylum in the States, where he emigrated with the help of Peggy Guggenheim and Varian Fry.

Knowing nothing of Ernst’s fate, Carrington sold their house and fled to neutral Spain. Devastated, she suffered a mental breakdown at the British Embassy in Madrid. Hospitalized, Carrington was treated with convulsive therapy and heavy medications that had her hallucinating in and out of consciousness. Once released, Carrington fled to Lisbon and secured passage to Mexico by marring Mexican Ambassador Renato Deluc. There she lived for the rest of her life until her death in 2011.

Similarly to Colquhoun, Carrington’s quest for the discovery of female-centered spirituality was informed by Groves’ essay The White Goddess published in 1948, which awoke a renewed interest for pagan mythologies.

A popular myth for female Surrealist artists was that of a matriarchal origin of humanity: despite its historical accuracy, the myth provided an empowering image to women, reclaiming the female creation myth as a viable model for female creativity. Inspired by this new mythology, Second wave Surrealists women envisioned fantastical egalitarian societies where humans and nature lived in harmony: a vision of the future created through women’s agency.