Situated in the Drakensberg mountain chain, the lowest point of Lesotho is 1,400 meters (4,593 feet) above sea level, the highest low point of any country. In fact, the entirety of the country is dominated by mountains. It is for this reason that Lesotho is known as the Mountain Kingdom. Unsurprisingly, the mountains played a decisive factor in shaping the history of this small kingdom, completely surrounded by South Africa.

Lesotho has experienced a unique and storied history from its establishment in the early 19th century to the present day.

The Ancient Beginnings of the Kingdom of Lesotho

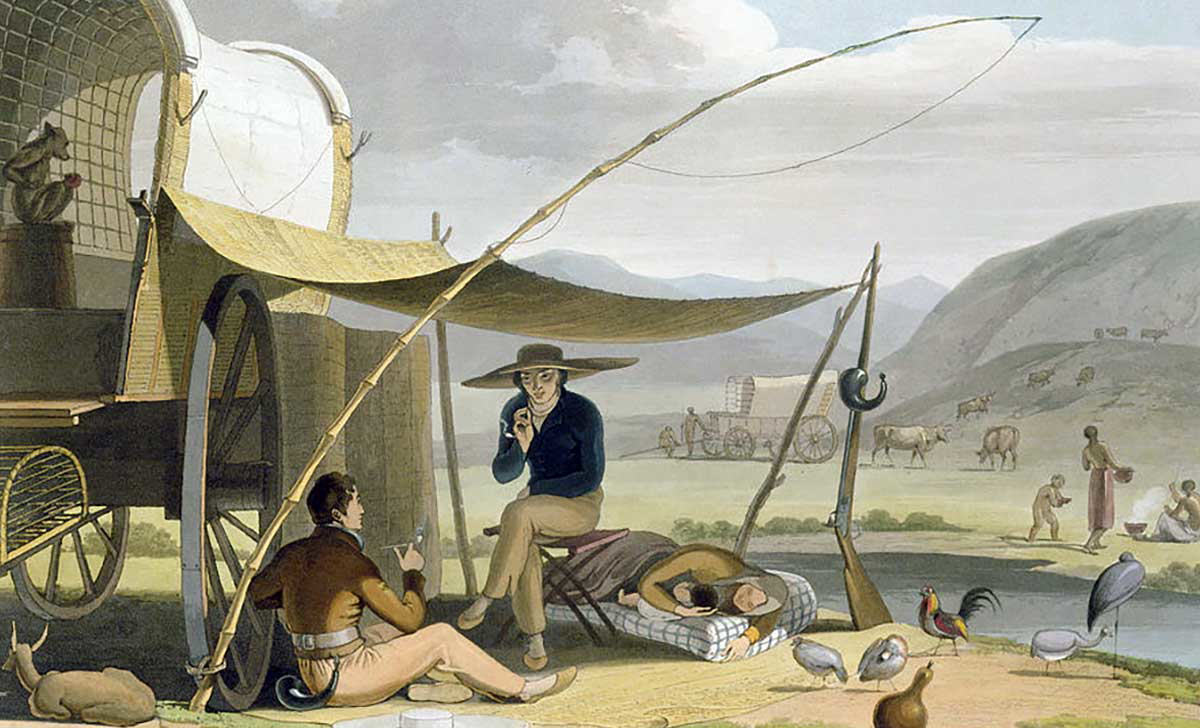

Long before Lesotho was ever realized as a state, the area that it now occupies was home to nomadic San people for thousands of years before they were displaced by Bantu migrations moving southwards. Around the 16th century, African farmers belonging to the Sotho people moved into the area, establishing villages and communities as they began to dominate the region.

These people represented the foundation of what would become a future independent state. In South Africa and Lesotho, the Sotho people that live in this region are referred to as Southern Sotho or Basotho, and while most live in South Africa, over 2.2 million Basotho people form the population of Lesotho today.

A Time of Turbulence and the Birth of a Nation

The beginnings of what would become a national identity and independent state were prompted by a time of massive upheaval known as the Difaqane, Lifaqane, or Mfecane, each meaning “scattering, crushing, forced dispersal, or forced migration.” The phenomenon is a subject of huge debate in Southern Africa, as the evidence of its causes and effects is open to academic challenge.

The most popular and widely accepted theory is that it was instigated by the military expansion of the Zulu Kingdom under the control of Shaka Zulu. However, it may have been exacerbated by drought and overpopulation, amongst other factors.

In this immensely violent time, huge numbers of refugees fled their homes in search of safety. Much of this safety was offered by the geographic features of what would become Basutoland, where independent chiefs held formidable and defensible positions in the mountains.

One such chief was King Moshoeshoe. In 1824, Moshoeshoe was attacked at Butha-Buthe, and although the attackers were driven off, Moshoeshoe became fearful that his position was not defensible enough. Seeking safety, Moshoeshoe and his people, many of whom were refugees fleeing the Lifaqane, trekked 72 miles (116 kilometers) to the Qiloane plateau, later renamed Thaba Bosiu, where the positions were more defensible. The journey was difficult. It took nine days, and Mashoeshoe’s grandfather fell victim to a group of cannibals known as the Malimo, who had been driven to desperation by the Lifaqane.

At Thaba Bosiu, Moshoeshoe set up camp and began what would evolve into a kingdom. He forgave the Malimo and lent them cattle to lift them out of poverty. This practice of lending cattle, known as mafisa, played an important role in bringing local clans together, which became the core of the Basotho nation.

Before long, missionaries arrived, introducing new crops and livestock to Basutoland. Schools were built, and the first books were printed in Sesotho. Under Moshoeshoe’s long reign, Basutoland became an independent state with considerable diplomatic power, but the future would not be defined by peace and security.

Conflict With Europeans

In the 1830s, there was contact with Boers trekking northeast from the British-owned Cape Colony. These new arrivals attempted to colonize lands north of the Caledon River, an area they claimed had been abandoned by the Sotho people. In an effort to shield himself and his nation from this encroachment, Moshoeshoe signed a treaty in the Cape Colony with the British, who subsequently annexed the territory claimed by the Boers. This foresight shown by Moshoeshoe guaranteed the autonomy of his state and proved the king’s wisdom in dealing with colonial threats. In 1852, a clash between Moshoeshoe’s forces and the British regarding Basotho cattle raiding threatened to turn into a war, but Moshoeshoe’s insistence on settling the dispute diplomatically prevented further conflict.

The following years proved bloody as the Sotho and the Boers competed for land. After three decades, the Boers managed to secure vast areas beyond the Caledon River. This land became part of the independent Boer republic known as the Orange Free State. Seeking protection, Moshoeshoe sent an appeal to Queen Victoria, and in 1868, Basutoland was annexed as a British protectorate.

Complete Annexation

In 1869, the Governor of the Cape and the Boers of the Orange Free State signed the Treaty of Aliwal North, which delineated Basutoland’s borders. Much of the protectorate’s western territory was ceded to the Boer republic. The following year, Moshoeshoe died at the age of 84 and was succeeded by Letsie, his eldest son.

Basutoland was annexed by the Cape Colony in 1871, and Basutoland’s power structures immediately came under attack. Trade was restricted, and Basotho’s legislative powers were transferred to the parliament in Cape Town.

The Cape Colony passed the Peace Preservation Act in 1878, a move that allowed for the legal confiscation of firearms from the African population. Despite the offer of compensation, the Basotho people rose up in rebellion.

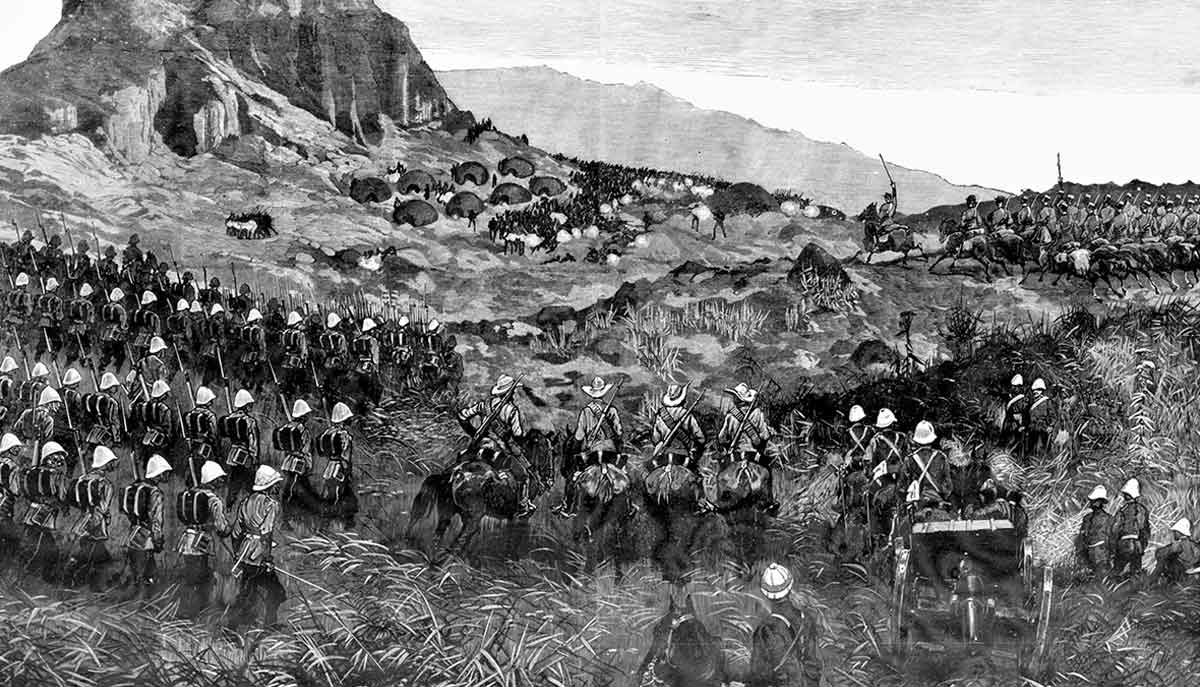

In 1879, a southern chief named Morosi rose up in revolt to defend the independence of his territory south of the Orange River. While Britain refused to help the Cape Colony deal with the situation militarily, Letsie, the paramount chief, along with many of the other chiefs, helped the Cape Colony, and Morosi’s forces were crushed. Basutoland and the Cape Colony were, however, by no means on good terms. The attempt to disarm the Basotho people led to war in September 1880.

The conflict was financially draining on the Cape Colony, and there was little to show for the war effort. On April 29, 1881, Sir Hercules Robinson, the High Commissioner of Southern Africa, announced an end to the conflict, and with further efforts of disarmament resisted, the Disannexation Act in September 1883 was passed, turning Basutoland into a British High Commission Territory rather than a part of the Cape Colony.

The following decades were marked by mounting tensions and war between Britain and the Boer Republics. On May 31, 1902, the devastating conflict that was the Second Anglo-Boer War came to an end, and the Boer republics were absorbed into the British Empire.

The Union of South Africa was created in 1910, merging the colonial possessions into a single polity. Basutoland, however, was not part of this arrangement and remained a separate territory under British rule until 1966.

Major Developments in the Mid-20th Century

Basutoland’s status as a colony remained unchanged for several decades, well into the second half of the 20th century. The winds of change, however, were blowing across Africa, and colonial territories were being granted independence. Basutoland was no exception to this dynamic.

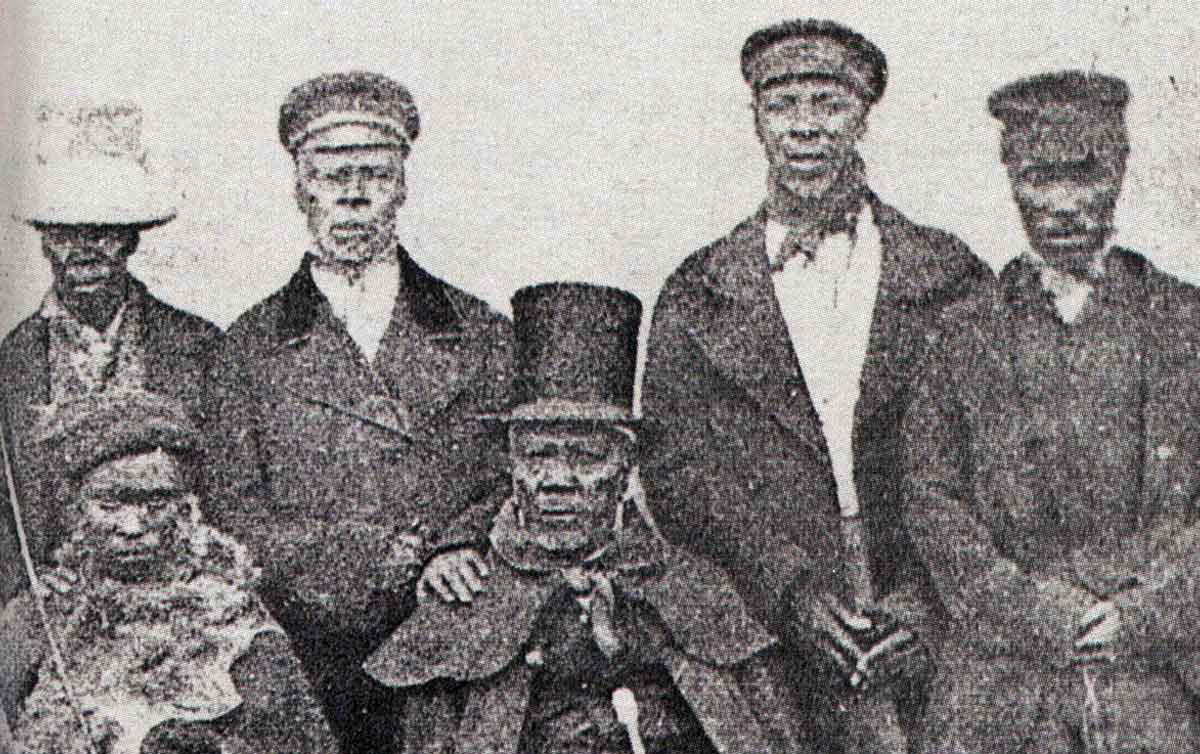

Political parties emerged in the 1950s that pushed for independence, and in 1966, independence was gained. Basutoland became the Kingdom of Lesotho with King Moshoeshoe as the head of state and Chief Leabua Jonathan of the Basotho National Party (BNP) as prime minister. Leabua Jonathan was one of the many great-grandchildren of Moshoeshoe who had around 140 wives.

Political developments, however, would be far from democratic. In 1970, the BNP lost the country’s first elections to the Basotho Congress Party (BCP). Leabua Jonathan refused to give up power and had the leadership of the BCP imprisoned. Despite creating a National Assembly in 1973, which included prominent BCP leaders, it was not enough to avoid rebellion.

In 1974, the BCP attempted a coup but was unsuccessful, and the BCP’s leader, Ntsu Mokhehle, went into exile. As the years passed, the international community provided aid to Lesotho, but the country’s problems of poverty and dependence on South Africa, which completely surrounded it, continued. Despite its economic dependency on South Africa, relations between the countries were not good. The Leabua Jonathan government remained hostile to South Africa, criticizing the policy of apartheid on multiple occasions.

In 1986, a military takeover of the government occurred, and Justin Lekhanya, as Chairman of the Military Council, ruled in conjunction with King Moshoeshoe II. In 1990, Lekhanya stripped the king of his executive and legislative powers. He announced the establishment of a National Constituent Assembly with the task of formulating a new constitution and returning the country to civilian rule. Before the country could transition, however, Lekhanya was ousted in 1991 by a group of officers. Letsie III was installed as king, and in 1995, he abdicated. The throne returned to his father, Moshoeshoe II.

Moshoeshoe died in a car accident the following year, and Letsie III became king again. By this time, however, a new constitution had been enacted, leaving the monarchy without any executive power. The BCP had won a landslide victory in the 1993 elections, and Ntsu Mokhehle became the prime minister.

The next few years were marked by violence and unrest, in part as a result of South Africa dismantling the apartheid regime. This resulted in employment opportunities for South Africans and reduced employment opportunities for the people of Lesotho, who had relied on opportunities within South Africa.

South Africa Intervenes

Mokhehle was dismissed by the BCP in 1997, and he went on to form his own party, the Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD). With two-thirds of the parliament supporting him, he remained as prime minister, and the BCP became the opposition party in government.

Elections were held again in 1998, with the LCD winning in a landslide, claiming 79 of the 80 seats in parliament. Opposition parties were up in arms, claiming the elections were fraudulent. Unrest and violence gripped the country, and the LCD requested South African help in quelling the unrest and restoring order. On September 22, 1998, troops from South Africa and Botswana (representing the Southern African Development Community, or SADC) entered Lesotho.

Despite the widespread looting and destruction, the SADC forces restored order, and Lesotho agreed to create an Interim Political Authority (IPA) to prepare for elections in 2000. The IPA was made up of representatives from Lesotho’s major political parties.

The Kingdom of Lesotho in the 21st Century

Developments in Lesotho’s political sphere remain far from ideal. In 2014, Prime Minister Thomas Thabane was forced to flee the country after he was named as a suspect in the murder of his ex-wife. In 2020, he formally stepped down from his post, and two years later, the charges were dropped.

Today, Lesotho is a country with many challenges. In 2007, a major drought pushed the government to declare a state of emergency, while HIV/AIDS continues to have a major impact on the country’s economy. About a fifth of the country’s 2.2 million people have the disease, but this rate is declining.

Despite the difficulties, there is plenty of hope for the small African country, especially in terms of its energy resources. In 2004, the country opened the first phase of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project, developed in partnership with South Africa. The project supplies water to the Gauteng region of South Africa and provides hydroelectric power to the people of Lesotho.

Current forecasts are generally positive in many areas, with the economy set to grow at a reasonable rate while agricultural yields and the manufacturing sector continue to expand. The tourism industry is also growing, which is not surprising given the spectacular beauty of the country. With scenic drives, incredible vistas, and an environment perfect for hiking and other outdoor activities, the Kingdom of Lesotho is a country that begs further investigation from the foreign sector.