Following Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1825, the Congress of Vienna aimed to draw a new map of Europe. During the negotiation processes, the area of Moresnet, a small village in the province of Liège, modern-day Belgium, posed challenges as both the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Prussia sought to acquire influence over the resource-rich region. The solution was found in establishing the independent Neutral Moresnet in 1816.

The Congress of Vienna & Establishment of Neutral Moresnet

In June 1815, after the defeat at Waterloo and the first abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte, a long era of war in Europe came to an end. From September 1814 to June 1815, representatives of victorious countries (Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria, and Prussia), known as the great powers, and other sovereign states held the Congress of Vienna to redraw the map of Europe. The task was characterized by arguments and disputes over the distribution of territories. Among these debates was the issue of the small territory of Moresnet, located in modern-day Belgium.

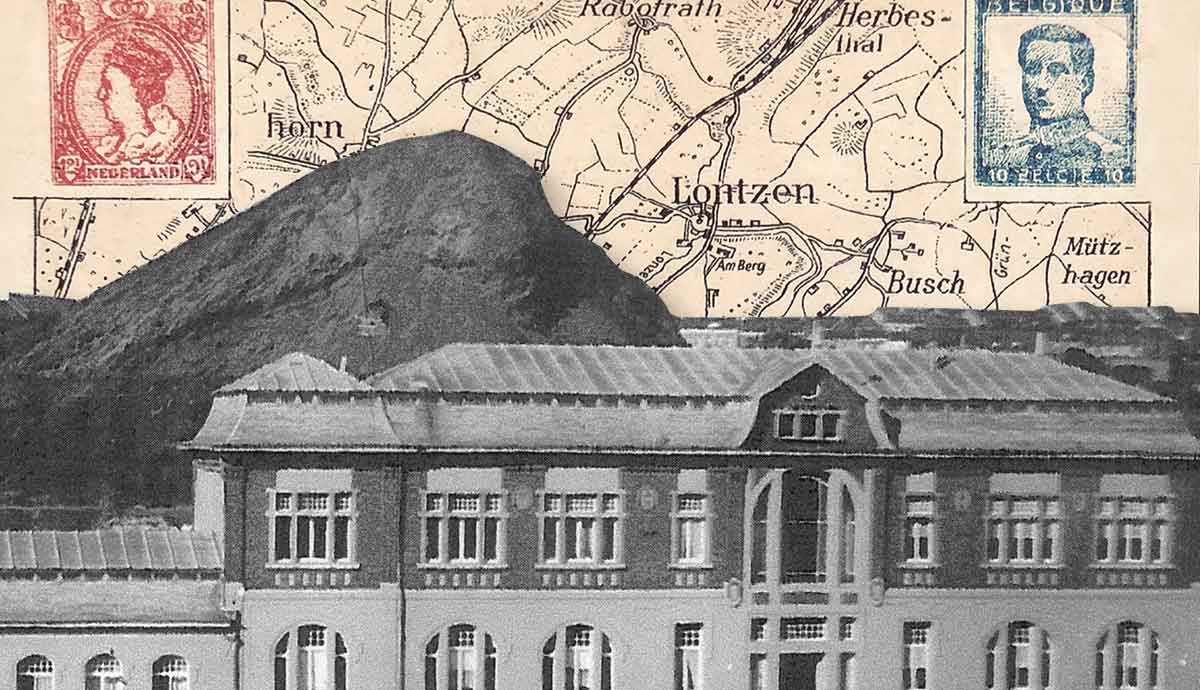

In the 19th century, a small land named Moresnet was stretched between two great powers: the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Prussia. Both of these great powers were eager to incorporate the territory into their borders and were unwilling to make concessions during the negotiations at the Vienna Congress.

The reason behind this was that Moresnet held a rich source of a lucrative mineral: zinc. The mineral was in high demand at that time, as it was widely used to produce brass. Brass, in turn, was an essential component of many industrial processes, including ammunition and other military equipment production. Hence, seizing control over the tiny land of Moresnet was perceived as a strategic move, guaranteeing access to highly profitable and economically significant resources.

Representatives from Prussia and the Netherlands met in neighboring Aachen (in modern-day Germany) in December 1815. The negotiations lasted several months. On June 26, 1816, the two powers reached an agreement. As the Congress of Vienna’s declared aim was to establish a balance of power and maintain peace in the world, the participating sovereign states decided to declare the territory a neutral zone indefinitely, and the term Neutral Moresnet was born.

Article 17 of the 1816 Treaty of Aachen stated:

“Since both commissions [of delimitation] have been unable to agree upon the way in which [the area would be separated], […] the above-mentioned town […] will be subject to a joint administration and shall not be militarily occupied by any of the two powers.”

The following factors led to the decision’s approval: By declaring neutrality, future conflicts between Prussia and the Kingdom of the Netherlands would be avoided. In a wider context, the economic benefits of the zinc mines could be enjoyed not only by the neighboring countries but also collectively. Third, neutrality was perceived as an innovative, experimental solution to the territorial disputes. If successful, it could assist great powers in resolving future conflicts over territories and preserving peace and stability throughout Europe.

The newly established Neutral Moresnet was tiny. Its territory was shaped like a triangle and encompassed only about fifty houses, which accommodated 256 people, a church, and the mine.

Administration of Neutral Moresnet

As determined at the Congress of Vienna, Neutral Moresnet was governed as a “condominium” under joint administration by the governments of Prussia and the Kingdom of the Netherlands. A special joint committee, composed of commissioners from each respective party, was established to oversee the administration processes. Commissioners were also granted the right to elect a mayor of Neutral Moresnet.

Neutral Moresnet was governed under the laws of the Napoleonic Code. Moresnet had neither a law court nor a prison. Prussian and Dutch judges would come and, if needed, convict on the basis of the Napoleonic civil laws. To tackle pending administrative matters, a ten-member city council was founded in 1859, though it only maintained an advisory function. In 1830, following the successful Belgian Revolution for independence from Dutch rule, Belgium became Neutral Moresnet’s neighboring country.

Neutral Moresnet benefited from tax-free trading conditions as it was not subject to any country’s jurisdiction. Due to this profitable environment, the company Vieille Montagne, which owned and operated the zinc mines, experienced an unprecedented increase in revenue. Throughout Neutral Moresnet, the company ran banks, educational institutions, residential houses, stores, and hospitals.

Neutral Moresnet did not have its own currency. The French franc was primarily used for financial transactions. Additionally, the currencies of Prussia, Belgium, and the Kingdom of the Netherlands were also recognized as valid forms of payment. In 1848, local coins were minted but were not regarded as legal tender.

Moresnet was not required to have military personnel since it was a neutral country. Its residents weren’t compelled to enlist in the army as there was no legal justification. In 1854, Belgium requested its citizens who had relocated to Moresnet to serve in the army. Prussia followed in the footsteps of Belgium in 1874. Subsequently, the exemption applied only to descendants of the original inhabitants of Neutral Moresnet.

Information regarding the benefits and privileges of relocating to Neutral Moresnet quickly spread throughout the European continent, and just ten years after Moresnet’s declared neutrality, its population doubled. Some were interested in avoiding military service; others enjoyed a tax-free zone, no import tariffs and customs checks so they could boost their business profits; and because there was no law guiding the extradition procedures, criminals fled to Neutral Moresnet to find shelter and avoid being convicted. However, these benefits were obtained at the expense of being considered stateless; Neutral Moresnet’s citizens did not have voting rights.

Neutral Moresnet as a Micronation & the First Esperanto State

In Europe, Neutral Moresnet was gradually gaining prominence. With its population increasing, Moresnet’s aspiration to form a national identity gained momentum. Among the most well-known individuals fascinated by the distinctive characteristics of Neutral Moresnet was Dr. Wilhelm Molly, the chief medical doctor of the Vieille Montagne zinc mine.

In 1895, Dr. Molly publicly initiated his plans for nation-building in the micro-nation of Neutral Moresnet. His desire to strengthen the residents’ sense of unity and national identity led him to personally design the flag, anthem, and postage stamp for Neutral Moresnet. Moresnet’s flag

featured horizontal red, white, and blue stripes. The anthem, composed in 1908, was named “Wilhelmus,” after King William I of the Netherlands. The postal stamps were never put into official circulation, yet collectors still find them incredibly valuable in the 21st century.

Since language plays a crucial role in forming a national identity, Dr. Molly proposed using the first man-made language, Esperanto, to establish the first Esperanto-speaking state named Amikejo instead of Neutral Moresnet. Amikejo meant “the place of friendship” in Esperanto. Neutral Moresnet would have been the world’s first complete Esperanto state had it been implemented successfully. Even though some Neutral Moresnet inhabitants began learning Esperanto, and Dr. Molly frequently used it during his medical practices, the linguistic revolution never materialized.

At the beginning of the 1880s, Neutral Moresnet’s zinc mine was running out of resources. Concerns regarding what might occur to its economy if the zinc mines were shut down surfaced. In 1885, the Zinc Mining Company of Vieille Montagne closed. They later resumed operating as a zinc smelting factory, continuing to be the principal employer of the inhabitants of Neutral Moresnet.

The Beginning of the 20th Century & the Demise of Neutral Moresnet

At the beginning of the 20th century, the population of Neutral Moresnet gradually increased from just 256 in 1816 to about 4,500 inhabitants. Trying to keep up with the rapid industrialization in Europe, a new power plant was constructed in Moresnet. To increase and strengthen self-governance capabilities, a police force and fire brigades were established. In 1903, the first casino was built in Moresnet, hosting numerous guests from around Europe.

The threats of disappearance at the end of the 19th century due to the exhaustion of zinc and subsequent economic failure were soon reborn in the wider context of World War I. Already on August 9, 1914, Germany invaded Belgium and acquired the territory of Moresnet without any military confrontation. In just one day, Germany achieved what the Kingdom of the Netherlands and Prussia had long desired: Moresnet was no longer a neutral self-governing entity. Germany claimed control over its territories, though without international recognition.

World War I lasted until 1919. Germany was ultimately defeated, and the war-ending Treaty of Versailles decided to grant Belgium the territory of Neutral Moresnet in the form of the municipality of Kelmis, along with other German-speaking borderlands, as part of Germany’s reparations. All the neutrals received Belgian citizenship. The decision was enforced on January 10, 1920.

“It was a poignant end to a hopeful experiment, as the territory was consumed by the very conflicts its ‘neutrality’ was meant to avoid,” noted historian Lucien Kelm in his book Moresnet: Europe’s Forgotten Nation.

Despite its absorption into Belgium, Neutral Moresnet’s legacy endures. The Vieille Montagne Museum in Kelmis, Belgium, provides a rare opportunity for interested parties to experience the distinct characteristics of the first neutral territory, Moresnet, and houses exhibitions dedicated to the region’s industrial, cultural, and political heritage.

The history of Neutral Moresnet is often utilized in different theoretical approaches. Particularly for libertarians, “Moresnet demonstrated the possibilities that statelessness holds out for peace, prosperity, and good order,” US financial trader and economist Peter C. Earle wrote in a 2014 study, A Century of Anarchy.