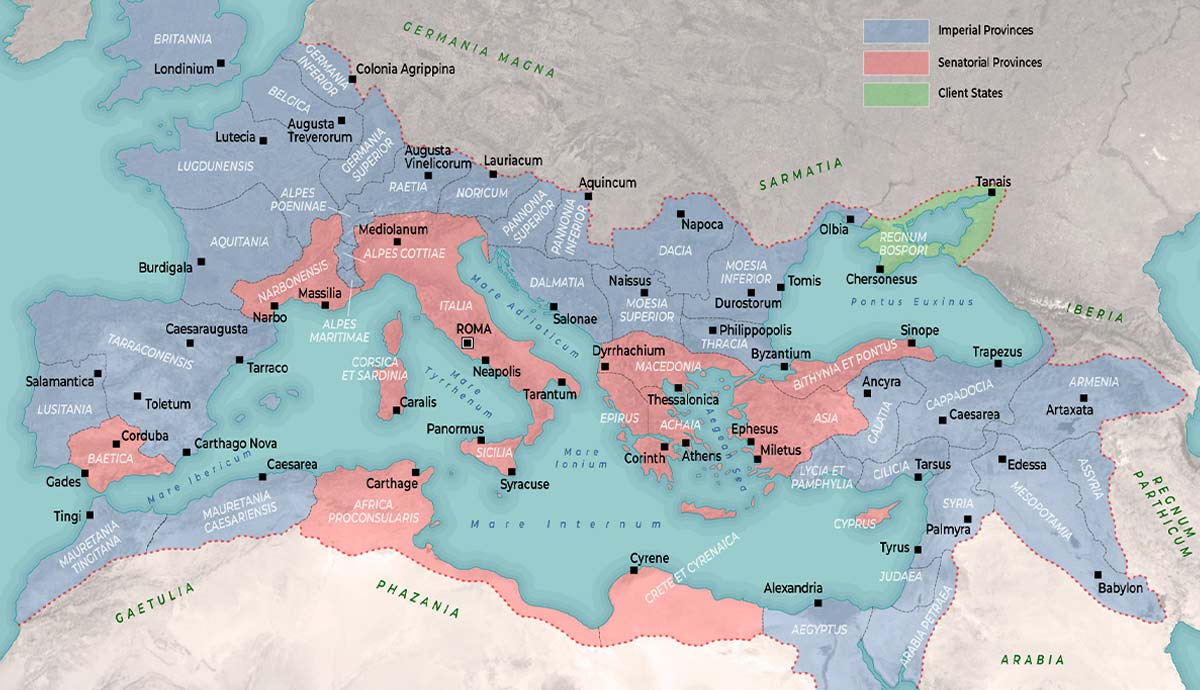

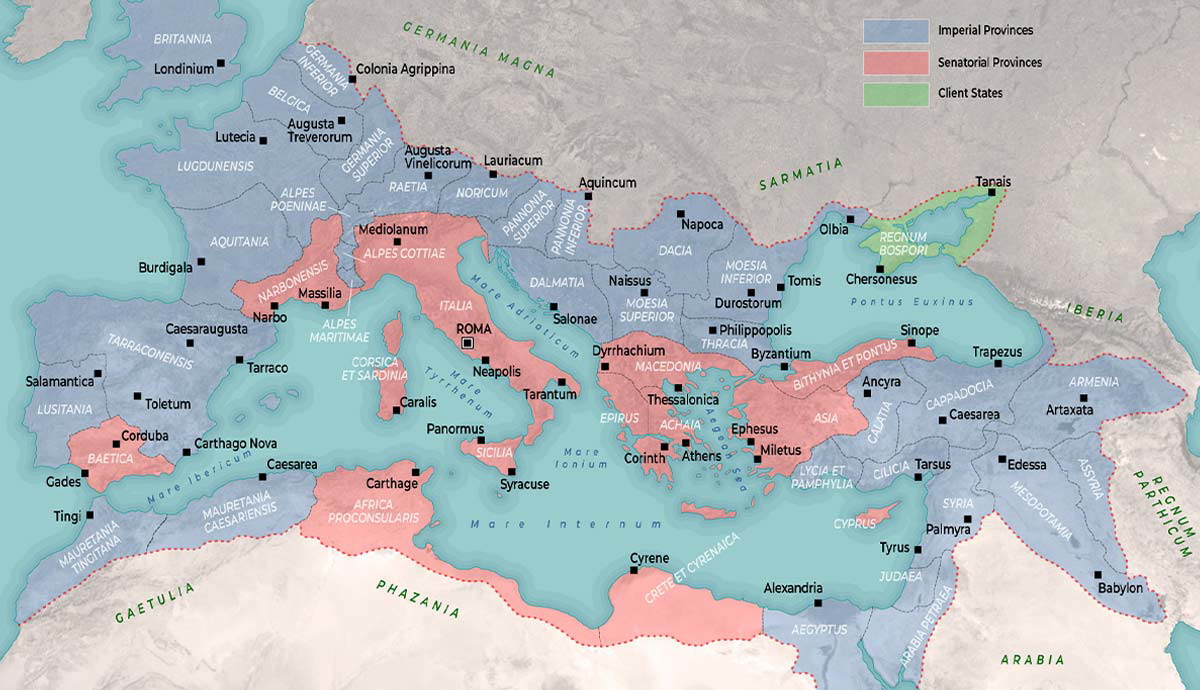

From its humble beginnings as a small city-state on the banks of the Tiber, Rome grew into an Empire covering around five million square kilometers by the early 2nd century CE. How did the Romans govern such a sprawling Empire? They developed an administrative unit called a “province” that incorporated these far-flung regions into the existing Roman governing system. The first was created in the 3rd century BCE, and there were more than 50 at the end of the reign of the emperor Trajan in 117 CE. How did the Roman province develop as an administrative unit, and what influence did it have on Roman politics? When did the different provinces become part of the Roman Empire? And what was life like in the Roman provinces?

Provincia: The Emergence of the Roman Province

In the early and middle Republic, when Rome was mostly concerned with dominating the Italian peninsula, the Romans used the term provincia to refer to the portfolio assigned to a magistrate. For example, a quaestor could be given the provincia of managing the treasury, or a consul could be given the provincia of leading a war against an enemy.

As Roman influence expanded across the Mediterranean, it gained overseas interests. This was largely linked to their conflict with Carthage, starting with their battle for Sicily and the important maritime trade routes it unlocked. When Rome gained dominance of Sicily at the end of the First Punic War (264-241 BCE), it moved from the offensive to the defensive. Rome needed to keep an eye on their interests in Sicily, so a quaestor, one of the first offices on Rome’s ladder of public magistracies, was given the provincia of Sicily. Before the end of the century, they were replaced by a higher-ranking praetor. This made Sicily the first Roman province.

There was no immediate thought of replicating the Sicilian precedent. Publius Sulpicius Galba Maximus, an ancestor of the later emperor Galba, received Macedonia as a provincia in 211 BCE. But when the conflict was resolved following the Third Macedonian War, rather than creating a province, the region was divided into four client kingdoms that paid tribute to Rome. Macedonia would only come under direct Roman control as a province following the Fourth Macedonian War in 148 BCE.

Except for Macedon, the other early provinces acquired by the Roman Republic were all linked to their conflict with Carthage. Sardinia and Corsica were annexed for direct control as a provincia in 237 BCE after they were taken from Carthage. Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior were both taken from Carthage following the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE). They were divided, with the River Baetis as their border, to clarify the independent provincia of the two commanders in the area. North Africa, including areas of modern Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya, was made a province following the destruction of Carthage at the end of the Third Punic War in 146 BCE.

These provincia were usually assigned to praetors who had imperium, which was the power to command Roman armies. They were also sometimes given to ex-praetors following their term in office, with pro-praetorial imperium. They could also be commanded by ex-consuls with proconsular imperium. Regions that were in active conflict were often assigned to the consuls in office.

Formalizing Provincial Governorships

During the Roman Republic, provinciae of already pacified regions weren’t attractive to ambitious Roman politicians as they offered little opportunity for military glory. However, soon, many took the opportunity to profit from their commands through financial exploitation and outright robbery. The story belongs to the later Republic, but the most famous example was Cicero’s prosecution of Gaius Verres for corruption while “governor” (this was not a term used by the Romans) of Sicily. He was accused of ruinous tax extortion, theft of private property, and abuse of power.

In response to growing accusations of corruption, which threatened Roman control of regions and went against Roman ideals of virtue and honor, the lex Calpurnia de repetundis was passed in 149 BCE. This established Rome’s first permanent criminal court, specifically to deal with crimes committed by provincial governors, which was where Verres was tried in 70 BCE.

At this time, the Senate assigned provincial commands largely as it wished, typically assigning provinces by lot or mutual agreement. Steps were taken to formalize this process when, in 123 or 122 BCE, the tribune of the plebs Gaius Gracchus passed the lex Sempronia de provinciis consularibus, requiring the Senate to announce which provinces would be commanded by the consuls prior to consular elections. This forced the geographic provinces to be more stable, as it became more challenging for the Senate to create new geographic provincia on an ad hoc basis as needed.

Gallia Narbonensis, the region of southern France, was annexed as a province in 120 BCE following attacks on the Greek city of Massalia in the region, a Roman ally. Rome stepped in, defeated the Allobroges and Averni, and then took the region. Asia became a province in 129 BCE, when the Attalid client kingdom was bequeathed to Rome by Attalus III. Attalus probably had little other choice due to growing Roman dominance in the region and the threat of internal bloodshed, as he had no heir. Around this time, more praetors were added to the number elected annually as more were needed to manage the growing number of provinces.

Italy was also divided into eleven provincia, though they were not provinces in the same sense, as the Italians received Roman citizenship during the Social War (91-88 BCE). These were I Latium et Campania, II Apulia et Calabria, III Lucania et Brutii, IV Samnium, V Picenum, VI Umbria et Ager Gallicus, VII Etruria, VIII Aemilia, IX Liguria, X Venetia et Histria, and XI Transpadana.

Late Republican Super-Provinces

Corruption cases aside, the Roman system of provincial governorship worked well as an extension of the Roman political system, which was designed to prevent any single man from gaining too much power. But this system began to break down when the general Gaius Marius used a friendly tribune of the plebs to reassign the provincia of Numidia, which was already assigned to Quintus Caecilius Metellus, to him, allowing him to assume command of the Jugurthine War (111-105 BCE).

This set a precedent that allowed the generals of the late Republic to use special laws to carve out huge geographic provinciae for themselves. Pompey had the lex Gabinia de piratis persequendis passed in 67 BCE, which gave him command of every province that was within 50 miles of the Mediterranean Sea so that he could deal with a pirate threat. This means that he had power over almost every province. This, and other extraordinary commands in the East, gave Pompey the power to annex several more Roman provinces, including Crete et Cyrenaica, Bithynia et Pontus, Syria, and Cilicia.

The consul Julius Caesar, with the help of his first triumvirate allies Pompey and Crassus, had the lex Vatinia passed in 59 BCE that assigned him pro-consular command of both Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum. When the governor of Transalpine Gaul unexpectedly died the same year, it was also awarded to Caesar. The command was given for five years, rather than the usual one year, allowing him to carry out his famous Gallic Wars. Pompey and Crassus then supported him again, passing the lex Pompeia Licinia in 55 BCE, which extended his command by another five years.

This represented a major threat to the Roman system, as Caesar’s extraordinary command allowed him to enrich himself and build personal loyalty with his now veteran army. However, when his term ended, he could also be prosecuted for corruption in the courts by his enemies, which now included Pompey. Caesar tried to avoid this by getting elected consul in absentia before returning, and therefore immune from prosecution. Pompey blocked this path, saying that he would have to give up his command and return to Rome before he could stand for election. This led Caesar to decide to march on Rome with his army, launching the civil war that would see the Republic replaced by imperial rule.

Imperial Provinces

During the second triumvirate that emerged after the assassination of Caesar, control of the provinces was divided between Caesar’s successors, Mark Antony, Lepidus, and Octavian. The division changed as the power balance between the three changed, and the men were able to enrich themselves as Caesar had done. But when Octavian defeated Antony at Actium in 31 BCE, all the provinces were placed under his command, confirming that Rome and its Empire were now under one-man rule.

In 27 BCE, when Octavian was holding his seventh consecutive consulship, he began taking steps to formulate and “normalize” his power within the surviving shell of the old Republic. This was the same year he accepted the title Augustus. He made a great show of returning control of the provinces to the Senate, but then at a Senate meeting that same year, he orchestrated the Senate giving him direct control of Spain, Gaul, Syria, Cilicia, Cyprus, and Egypt, for ten years in the first instance. These provinces contained 22 of Rome’s 28 standing legions at the time.

This division between senatorial and imperial provinces became permanent. The peaceful senatorial provinces were managed by the Senate, which appointed governors in the traditional way. However, considering the emperor’s power in the Senate, he had significant influence over these appointments.

Augustus, technically in direct command of his province, appointed subordinate legates to oversee his provinces on his behalf, with the official title legatus Augusti pro praetore. Importantly, while these legates held imperium, they were subordinate to Augustus, who held maius imperium, which gave him the power to overrule any provincial governor. This meant that any victories won by the legates did not belong to them, but to Augustus. So, they could not celebrate triumphs for their victories.

Exceptions were sometimes made to this rule. Augustus allowed his stepson and, at the time, potential heir, Tiberius, to celebrate a triumph in 7 BCE for his victories in Germany.

Many new provinces were incorporated into the Roman Empire under Augustus, largely through the consolidation and reorganization of territories won prior to his reign. The most important new province was Egypt, which Julius Caesar took control of in 47 BCE, but was treated as the personal possession of Caesar, then Antony, and then Octavian. Because of the power and wealth of Egypt, it was believed that the governor of that province could challenge imperial power. So, rather than a regular legate, Augustus appointed a lower-ranking equestrian governor, giving Augustus greater control.

Achaia (Greece) was made a separate province from Macedonia under Augustus. Hispania was reorganized into the provinces of Hispania Tarraconensis, Baetica, and Lusitania. Caesar’s Gallic conquests were organized into Illyricum, Aquitania, Gallia Lugdunensis, and Gallia Belgica. North Africa was consolidated into Africa Proconsularis. Client kingdoms were bequeathed or annexed as provinces, such as Galatia and Judaea.

The Limits of the Empire

Before he died, Augustus reportedly advised his successor, Tiberius, not to expand the Empire beyond its current borders, as the Empire had already reached its workable limits. While the Empire continued to expand, it did so on a much slower scale, primarily through relatively peaceful annexation. Some notable exceptions included Britannia, taken during the reign of Claudius, who needed to prove his military credentials, and Germania Superior and Germania Inferior, taken under Domitian, who also needed to prove his military chops. Trajan also famously conquered the province of Dacia. The Roman Empire reached its greatest extent under Trajan, with few new territories added following his reign.

The nature of the Roman provinces changed near the end of the 3rd century when Diocletian introduced the Tetrarchy. This was a major administrative reorganization that, among other things, saw the empire reorganized into more than 100 provinces.

Life in the Roman Provinces

Life in the Roman provinces would have depended on where and when you lived. In general, life was a blend of forced Romanization and enduring local tradition. For example, we see the spread of the Latin language in the West, though Greek continued to be the lingua franca in the East.

There was also a meeting of religious practices. The cult of the Roman emperor was encouraged, with temples set up by locals in the East, and the Roman authorities setting up altars in the West and requiring local worship. While Rome expected provincials to respect their gods and perform sacrifices to maintain their favor, they also respected local deities and customs, allowing them to continue and mixing them with Roman practices. The exception to this was Judaism and Christianity. Because these religions were monotheistic, their devotees did not participate in Roman sacrifices. This was the problem, rather than the religions themselves.

The Romans brought infrastructure such as roads, sewage, and public baths that improved daily life. They also made enormous tax demands, which placed stress on agriculture and pushed some of the poorest into forced labor. There were sometimes local grain shortages in the provinces because so much grain was sent to Rome.

Newly conquered provinces had a strong Roman military presence that must have felt imposing. Locals were also pressured to enlist in the Roman army as auxiliary non-citizen troops. After 25 years of service, they could earn Roman citizenship, which was passed on to their children, granting them rights and privileges that their neighbors did not enjoy. In combination with migration, this saw a wealthy Roman citizen class emerge across the Empire. Some even rose to the top position. Both Trajan and Hadrian were Roman citizens born in Hispania, while Septimus Severus was born in North Africa.

The emperor Caracalla granted blanket citizenship to all free men living within the Roman Empire in 212 CE. However, his reasons were probably not altruistic. This increased the number of people liable to pay taxes, such as inheritance and manumission taxes. It may have had little impact on people’s daily lives in practice, while undermining the value of Roman citizenship more generally.

List of Roman Provinces Under Trajan

At the death of Trajan in 117 CE, there were 40 Roman provinces, excluding the eleven Italian provinces.

| Province | Date | Notes |

| Achaea (Greece) | 146 BCE | Annexed by Rome as part of Macedonia in 146 BCE and made a separate province in 27 BCE |

| Aegyptus (Egypt) | 30 BCE | Conquered by Caesar in 47 BCE and made a province by Augustus following Actium in 31 BCE |

| Africa Proconsular | 146 BCE | Established following the Third Punic War and reorganized multiple times |

| Alpes Cottiae | 63 CE | Created under Nero |

| Alpes Graiae et Poeninae | 63 CE | Created under Nero |

| Alpes Maritimae | 41/54 CE | Created under Claudius |

| Arabia | 105 CE | Conquered by A. Cornelius Palma under Trajan |

| Asia | 133 BCE | Annexed from the Attalid Kingdom |

| Baetica | 237 BCE | Taken following the Second Punic War and organized into a province in 14 BCE |

| Bithynia et Pontus | 71/64 BCE | Bequeathed to the Romans |

| Britannia | 43 CE | Conquered under Claudius |

| Cappadocia et Galatia | 17 CE | Galatia was taken by Augustus in 25 BCE, and Cappadocia was annexed by Tiberius, combined as a single province in 70 CE under Vespasian |

| Cilicia et Cyprus | 64 BCE | Cilicia was conquered by Pompey in 64 BCE, and Cyprus was taken by Publius Clodius Pulcher in 58 BCE and added to Cilicia |

| Corsica et Sardinia | 238 BCE | Conquered after the First Punic War and split into two provinces in 6 CE |

| Creta et Cyrenaica | 67 BCE | Bequeathed to the Romans in 96 BCE, governed as a client kingdom, and then made a province in 67 BCE following uprisings |

| Dacia | 116 CE | Conquered by Trajan |

| Dalmatia | 19 BCE | A Roman protectorate since 168 BCE, taken by Octavian in 33 BCE, made part of Illyricum in 27 BCE, and made an independent province later under Augustus |

| Gallia Aquitania | 51 BCE | Conquered by Caesar and organized into a province by Augustus in 27 BCE |

| Gallia Belgica | 51 BCE | Conquered by Caesar and organized into a province by Augustus in 27 BCE |

| Gallia Lugdunensis | 51 BCE | Conquered by Caesar and organized into a province by Augustus in 27 BCE |

| Gallia Narbonensis | 121 BCE | Following the conquest of the Averni and Allobroges |

| Germania Inferior | 83/84 CE | Created following Domitian’s campaigns in southern Germany |

| Germania Superior | 83/84 CE | Created following Domitian’s campaigns in southern Germany |

| Hispania Tarraconensis | 237 BCE | Taken following the Second Punic War and split into a province under Augustus |

| Lusitania | 237 BCE | Following centuries of conflict, finally defeated by Augustus |

| Lycia et Pamphylia | 74 CE | Lycia annexed by Claudius in 43 CE and made a single province under Vespasian |

| Macedonia | 146 BCE | Taken following the Macedonia Wars |

| Mauretania Caesariensis | 42 CE | Client state annexed by Claudius |

| Mauretania Tingitana | 42 CE | Client state annexed by Claudius |

| Moesia Inferior | 6 CE | Campaigns of Crassus in 29 BCE, consolidated into a province under Augustus, and made two provinces under Domitian in 85 CE |

| Moesia Superior | 6 CE | Campaigns of Crassus in 29 BCE, consolidated into a province under Augustus, and made two provinces under Domitian in 85 CE |

| Noricum | 15 BCE | Defeated by Publius Silius in 16 BCE and made a client kingdom under a Roman governor, made a province under Claudius in 40 CE |

| Numidia | 46 BCE | Annexed by Caesar, sometimes considered part of Africa Proconsularis |

| Pannonia Inferior | 10 CE | Campaigns of Octavian in 35 BCE and Tiberius in 9 BCE, incorporated into Illyricum, made a separate province in 10 CE following the put down of revolts the previous year, split in two under Trajan |

| Pannonia Superior | 10 CE | Campaigns of Octavian in 35 BCE and Tiberius in 9 BCE, incorporated into Illyricum, made a separate province in 10 CE, following the put down of revolts the previous year, split in two under Trajan |

| Raetia | 15 BCE | Danube campaigns of Tiberius and Drusus under Augustus |

| Silicia | 241 BCE | Taken after the First Punic War |

| Syria | 64 BCE | Taken by Pompey after the Third Mithridatic War |

| Syria Palestina (Judaea) | 6 CE | Annexed by the Romans, name changed to Syria Palestine following the Bar Kokhba revolt |

| Thracia | 46 CE | Annexed under Claudius |