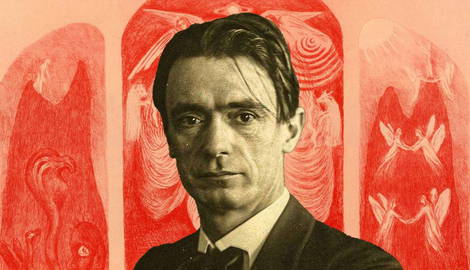

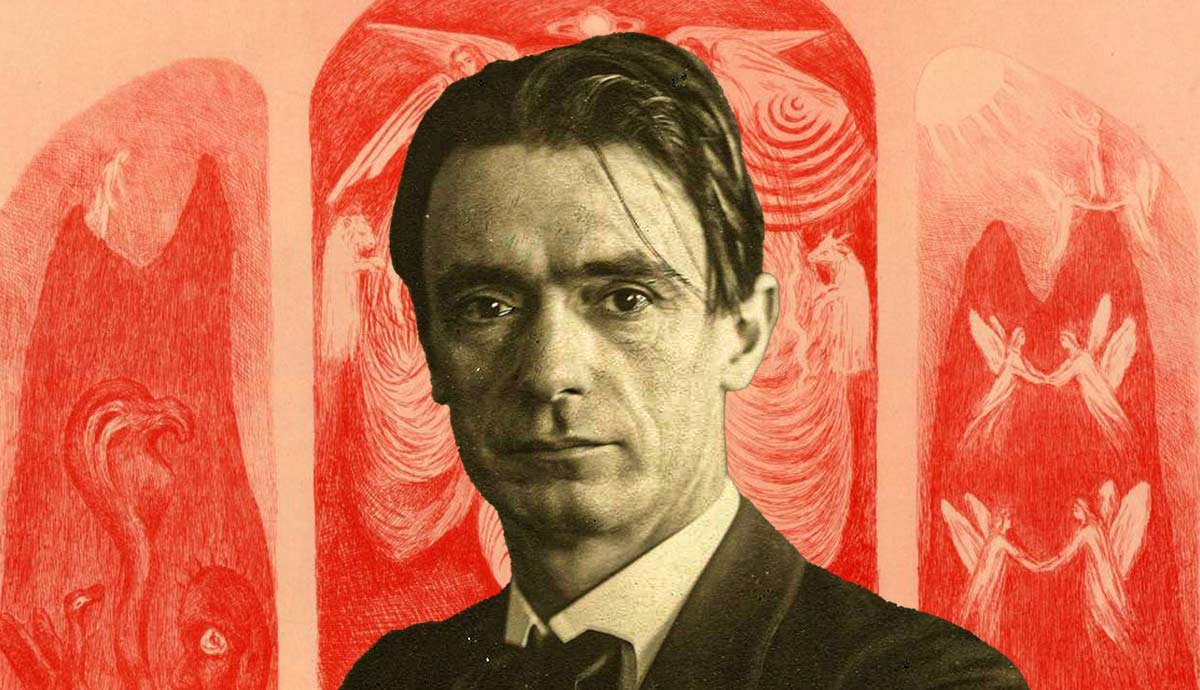

Rudolf Steiner was a German mystic who had a profound impact on the artists of his generation and beyond. Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, and many others were inspired by his ideas and sought guidance from him. Steiner was also an artist himself, inventing and promoting spiritually impactful forms of art. Read on to learn more about Rudolf Steiner, his views on art, and his impact on modern art.

Who Was Rudolf Steiner?

Rudolf Steiner was a German philosopher, literary critic, mystic, social reformer, alleged clairvoyant, and one of the most influential figures in the genesis of abstract art. Born in 1861 on the territory of present-day Croatia, Steiner was a talented and diligent student with a profound interest in both literature and science. Allegedly, as a child, he had visions and communicated with his deceased relatives. He began his career as an editor of Wolfgang Goethe’s writings on natural science. His fascination with Goethe remained with him for the rest of his life and fueled many of his theories.

Through the literary circles, Steiner became familiar with a then-popular doctrine of Theosophy, a philosophical and quasi-religious movement founded by Helena Blavatsky, a Russian-American writer and philosopher. Theosophists focused on the search for universal wisdom that united all existing religions and advocated for overcoming the man-made boundaries of race, gender, and religion to achieve spiritual enlightenment. Rudolf Steiner quickly became involved with the movement on the highest level, taking charge of its German branch. He published books and presented lectures, educated artists and creatives of all sorts, and preached the idea of creating art that would affect the spirit instead of simply pleasing the eye.

Steiner’s influence spanned far beyond the arts and occult philosophy. He was one of the founders of biodynamic farming and organic agriculture in general, promoting the treatment of soil, crops, and animals living on farms as a single organism with interrelated processes. Another famous invention of Steiner was Waldorf education, an educational philosophy centered around developing creativity and compassion and focusing on each child’s individual inclinations.

Steiner’s Breakup With Theosophy

Since his early days in the Theosophical Society, Steiner relied heavily upon Christianity, opposing most of the other leaders’ inclinations towards Hinduism and Buddhism. In 1909, Steiner quit the movement altogether due to an ideological conflict partially related to the movement’s leadership. Annie Besant, who took charge of the Society soon after the death of Helena Blavatsky, promoted the idea of a World Teacher, the messiah who would come to lead humanity toward new spiritual heights. She found him in a fourteen-year Hindu boy Jiddu Krishnamurti, who was adopted by the Indian branch of the movement. Steiner radically opposed it, insisting that humanity had outgrown its need for messiahs and needed to apply their own efforts to progress.

The conflict soon became insoluble, and Steiner went to found an alternative to Theosophy—the Anthroposophical Society. In contrast with the name Theosophy, which was translated as divine wisdom, Steiner’s Anthroposophy represented human wisdom. The teaching was based mostly on methods of natural science, Christian concepts, and Rosicrucianism—a Christian spiritual movement originating in the 17th century, calling for a reformation of knowledge and wisdom through studying alchemy, numbers, and magic.

To finish his separation, Steiner gave a series of lectures revealing the decline and corruption of his former associates. Steiner spoke of the anti-Christian orientation adopted by the theosophical movement under the leadership of Helena Blavatsky. He also accused the Theosophists of attempting to spiritually defeat the West through their propaganda of Eastern religious practices.

Steiner’s Art Theories

Similarly to many mystic thinkers at the time, Steiner based his entire body of theories on the concept of evolution. Taking Charles Darwin’s theory as the basis, he applied it to the notion of the spiritual development of humankind in general and a single human being in particular. According to Steiner, there was a time between the emergence of the earth and the beginning of recorded history, where human beings existed as a single united spirit. Separated into many bodies, for they were left in a state of perpetual incompleteness. Thus, humans needed to transcend the boundaries of race, gender, and self-centered thinking to achieve harmony again.

The idea of the unity of all parts manifested itself in Steiner’s view of art. In his view, art was supposed to affect all human senses at once and rely on multiple forms in order to bring the human soul closer to the long-lost harmony. Art was supposed to bridge the gap between the human soul and mind, introducing scientific principles into purely aesthetic domains and bringing aesthetic harmony into products of reason. Such an approach was eagerly received by the pioneers of abstract art and other avant-garde forms of expression.

Still, all conscious scientific exploration had to consider the natural order of things. In Steiner’s view, impactful art had to follow the principles of the natural world. He advocated for the use of natural materials and attributed special spiritual meanings to various types of wood used in sculptures.

Steiner and Hilma af Klint

Rudolf Steiner was an important figure in the life and work of the famous Swedish pioneer of abstraction, Hilma af Klint. Af Klint was a member of the Swedish branch of the Theosophical Society and attended Steiner’s lectures in Stockholm. In 1908, Hilma af Klint sent a letter to Rudolf Steiner, inviting him to visit her studio. Initially, she asked for help with decoding her large-scale abstract works painted in a state of trance. She believed she was a medium to receive messages from some higher beings. Unable to interpret what her work meant for the world and what to do next, she looked for spiritual guidance from someone who was much more experienced in the field of unseen forces.

Steiner, however, was critical from the start. The Theosophic doctrine did not approve of mediumistic practices, seeing them as dangerous for the practitioners and potentially fraudulent for those who would want to exploit others’ beliefs. In that context, they were not wrong: since the advent of spiritualism, countless fraud investigations and accusations have taken place. Even the first well-known case of mediumistic practice performed by the famous Fox sisters was years later dismissed as fraud after the confession of one of the women involved.

Steiner’s dismissal upset the artist, yet she soon found a way to reinvent her artistic practice. In the 1910s, she left mediumship behind and focused on her own aesthetic and intellectual pursuits, creating geometric abstractions. In the 1920s, she visited Steiner in the Goetheanum, the headquarters of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland, and donated some of her works to the complex’s library.

Steiner, Mondrian, and Kandinsky

Apart from Hilma af Klint, Rudolf Steiner had connections with two other abstract pioneers, Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky. Mondrian was profoundly interested in Theosophy and owned several books of Steiner’s lectures translated into Dutch. He even sent several letters to Steiner explaining his art theories and ideas. However, Steiner never bothered to answer them as he, frankly, often did with incoming correspondence he was not interested in enough. Piet Mondrian’s occult influences were, in many ways, based on the writings of Helena Blavatsky and Josephin Peladan, which Steiner deemed outdated.

Steiner’s relationship with Kandinsky was significantly closer. Both men shared the idea of the necessity of the synthesis of all arts that would affect all human senses and elevate humanity’s spiritual consciousness. Like many others, Kandinsky attended Steiner’s lectures and, unlike others, actually received answers to his letters. Steiner and Kandinsky had several private meetings, including one soon after Steiner’s visit to Hilma af Klint’s studio. That coincidence led some researchers to believe that the then-obscure Swedish artist could have influenced Kandinsky through their mutual acquaintance.

Rudolf Steiner’s Artistic Practice

Steiner did not only write about art; he also practiced it and personally tested his proposed methods. His preferred technique was the so-called veil painting, which involved applying watercolor in thin layers with a wet brush on dry paper, creating overlapping fields of color. According to Steiner, veil painting resembled colored light and was supposed to stimulate various emotional responses, healing the mind and the body.

He also worked with sculpture, carving several wooden works for the Goetheanum. His most famous work was the multi-figured sculpture Representative of Humanity, designed and carved in collaboration with sculptor Edith Maryon. The symbolic figures of Christ, Lucifer, and Ahriman (Zoroastrian evil spirit which, for Steiner, represented destructive materialism) represented humanity’s quest for balance in emotions and ideas.

Rudolf Steiner died in 1925, leaving behind thousands of pages of writing and hundreds of supporters, as well as the enormous project of Goetheanum. After he died in 1925, the Anthroposophical Society descended into chaos. Unwilling to get involved in disputes over leadership, af Klint refused to travel to Dornach again until 1930, and other artists associated with him distanced themselves from the movement. Still, Steiner’s ideas had a great impact on modern and contemporary art, particularly on the famous conceptualist Joseph Beuys. Beuys frequently referred to Steiner’s writings and even borrowed some of his artistic techniques, creating similar artistic works in chalk.n chalk.