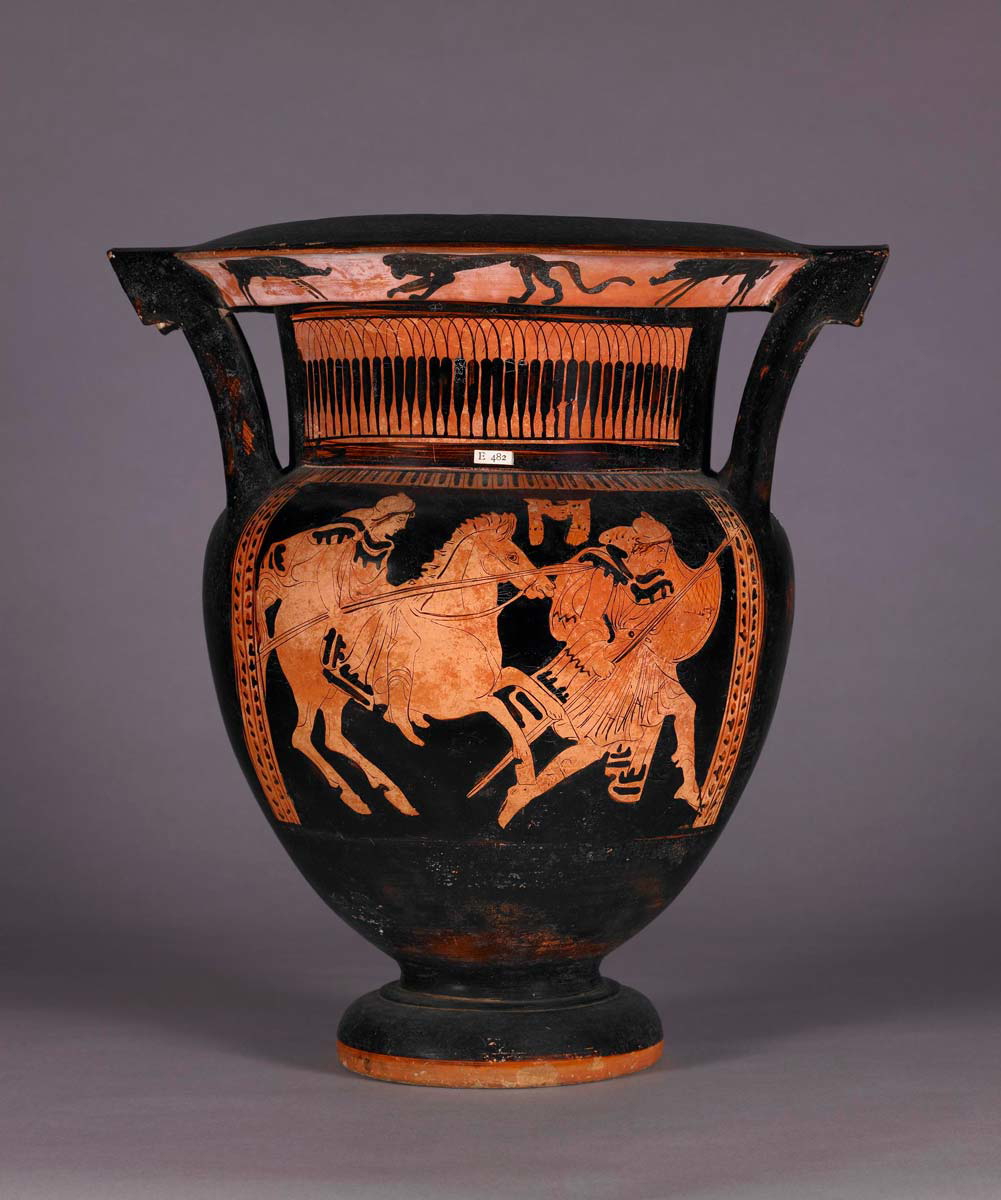

The ancient kingdom of Thrace was located in the north of the Aegean, encompassing an area between the Carpathian mountains, the Black Sea, and the Aegean Sea. Known for being horse-warriors, Thracian mercenaries were regular contingents in the ancient armies of the Greeks, Macedonians, and Romans. Being so near to Greece, Thrace was heavily influenced by Greek culture, and later Roman culture when they became a province of the Roman Empire.

Thracian Culture

The ancient Thracians did not have a unified state. Instead, they lived in numerous tribes, each with their own nobility and rulers. They knew themselves by their tribal names rather than by the moniker of “Thracian,” which was given to them by the Greeks.

Much of what is known about Thracian culture comes from the 5th century BCE historian Herodotus. He reported that the Thracians were polygamous, where the men had many wives. Upon the husband’s death, the wives would compete to determine who was the favorite, and she would have the honor of being buried at his side. This practice is borne out by archaeological evidence. Within a tomb discovered in Vrasta, a couple was found in the inner chamber where the woman had a knife through her chest. In the second chamber was another woman killed by a spear.

They were a culture of horse warriors, armed and armored with only a light shield and a javelin so they could remain mobile. They preferred a life of brigandage over farming, seeing the former as the only proper way for a man to earn a living. They were very effective at guerrilla tactics, and the Greeks found that the only way to properly deal with them was to have Thracian contingents in their own armies. As early as the 6th century BCE, Thracians were being hired as mercenaries around the Greek world.

The Thracians worshiped a god named Zalmoxis. He wasn’t a cosmic god in the same sense as Ares or Dionysus, but had begun as a legendary king of the Getae tribe. He taught them of the immortality of the soul and that no one truly died, but went to a place where people lived forever and received every conceivable good. When Zalmoxis died, he was resurrected three years later, proving his teachings true.

Herodotus recorded a ritual to communicate with Zalmoxis. Every five years, they chose a man by lot to send as an emissary to the god. Several men held the emissary by the arms and legs, while others held three spears. They rocked the man up and down and cast him onto the spears. If the emissary died, Zalmoxis looked favorably on them. If the emissary didn’t die, they blamed the messenger and performed the ritual again with a different man.

History of Thrace

The first mention of Thracians as a people was in Homer’s Iliad as allies of Troy, though settlements have been dated to approximately 6000 BCE. They began as agriculturalists and expanded into larger settlements as they discovered minerals that could be mined and smithed. Around 1500 BCE, a migration of peoples took place around the ancient world, which brought into Thrace the horse-riding warriors that were spoken of in ancient sources.

In the second half of the 7th century BCE, Greeks began to colonize the Aegean coast of Thrace. From the amount of times these colonial cities were destroyed and rebuilt, it is clear that the methods of colonization were never peaceful. Then, in the year 512 BCE, the Persians began advancing into Thrace, eventually conquering the southern tribes. The Persians administered their military affairs in the region from the cities of Doriskos and Ainos until 476 BCE, when they withdrew back into Asia.

Around this time, Teres of the Odrysian tribe began to conquer his neighbors, forming the Odrysian kingdom. After the Persian Wars, Athens gained preeminence in the Aegean through the Delian League. They were favorable to the Odrysian kingdom since in them they saw an ally against further Persian expansion. The Greek cities of the northern Aegean even stopped paying tribute to the Delian League, instead paying the tax to Teres, since they depended more on him for protection. Usually Athens would use force against allies that refused to pay tribute to the League, but they did not want to antagonize the powerful Thracian kingdom.

The Odrysian kingdom had three generations of relative calm before internal strife and external pressures caused its decline. Philip II of Macedon took advantage of the situation to push east into Thracian territory, and in the mid-4th century BCE they were forced to recognize Macedonian rule. Philip’s son, Alexander the Great, expanded the Macedonian empire from Europe into Asia, but after his death the empire fractured and Thrace came under rule of his general, Lysimachus. Lysimachus met with resistance ruling the Thracians and the turmoil after his death left space for an invasion by the Celts from central Europe.

The Celts looted cities throughout Thrace and along the Aegean coast, and some crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor, where they founded Galatia. Celtic rule of Thrace lasted from 279 BCE to 216 BCE, when the Thracians revolted and overthrew them with the help of the Macedonians. By 168 BCE, the Romans had appeared on the scene and had conquered both Macedonia and Greece, moving their way east into Thrace. Rome eventually annexed the northwestern part of Thrace by the mid-1st century BCE, creating the province of Moesia, while the southeastern part became a Roman protectorate ruled by the Odrysians. The Odrysian kingdom gradually became the new Roman province of Thracia.

Land of Ares

Thrace was also known as the home of Ares. We learn of this in Homer’s Odyssey. After Ares and Aphrodite’s affair was discovered by Hephaestus, Aphrodite fled to her home in Cyprus while Ares fled back to Thrace. A later account by Roman poet Ovid in his Fasti tells of Ares’ birth. Hera was upset that Zeus had given birth to Athena without her, so she decided to birth a child without him. With the help of a nymph named Flora, Hera used a flower from the fields of Olenus that was said to make even a barren heifer conceive at a mere touch of its petals. When Flora touched Hera with the flower she immediately became pregnant and went off to Thrace, where she gave birth to Ares. While Ares was not widely worshiped in Greece, representing the terrors and excess of war, Herodotus noted that Thrace worshiped no gods except for Ares, Artemis, and Dionysus.

Kingdom of Orpheus

Orpheus, while also said to be the son of Apollo and the nymph Calliope, was the grandson of the Thracian king Lycurgus, who tried to deceive and kill Dionysus when the god was crossing the Hellespont into Europe. Orpheus was a bard who went on the journey for the golden fleece with Jason and the Argonauts. His songs were so beautiful that they were able to drown out the songs of the sirens.

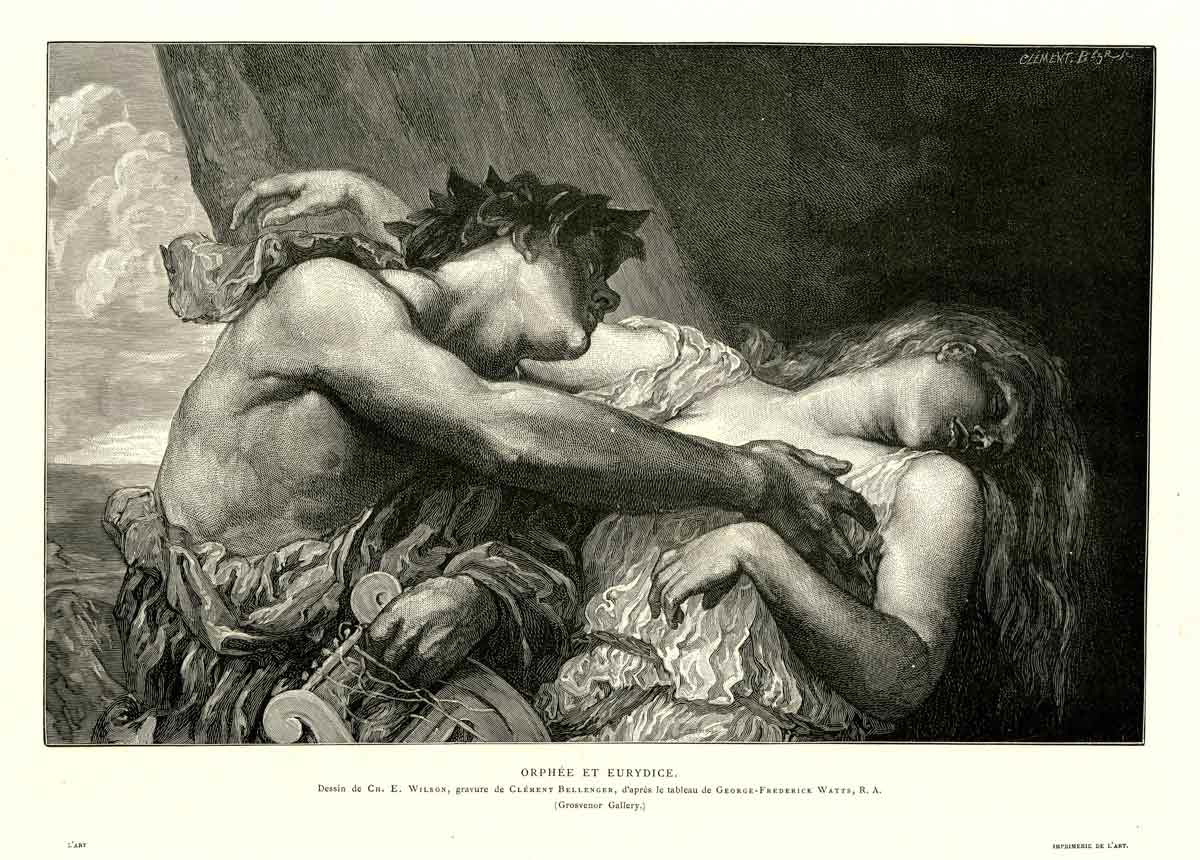

One of his more well-known myths concerned the death of his wife, Eurydice. She died from a snake bite, and in his grief Orpheus descended to the underworld to plead with Hades to give her another chance at life. He sang for the god, and all the spirits of the underworld, even the Furies, wept with sorrow for him. Hades and Persephone were moved and consented, calling Eurydice to them. They told Orpheus that he could return to the world with his wife, as long as he didn’t turn back to look at her. They began the climb up, but Orpheus couldn’t help but look back, and when he did, she instantly slipped back into the underworld.

Orpheus stayed faithful to his late-wife for the remainder of his life, which did not sit well with other Thracian women who tried to court him. He shunned all their advances and they grew to hate him for it. They attacked him, tearing him limb from limb. His shade descended down to the underworld, where he was at last reunited with Eurydice.

Home of Spartacus

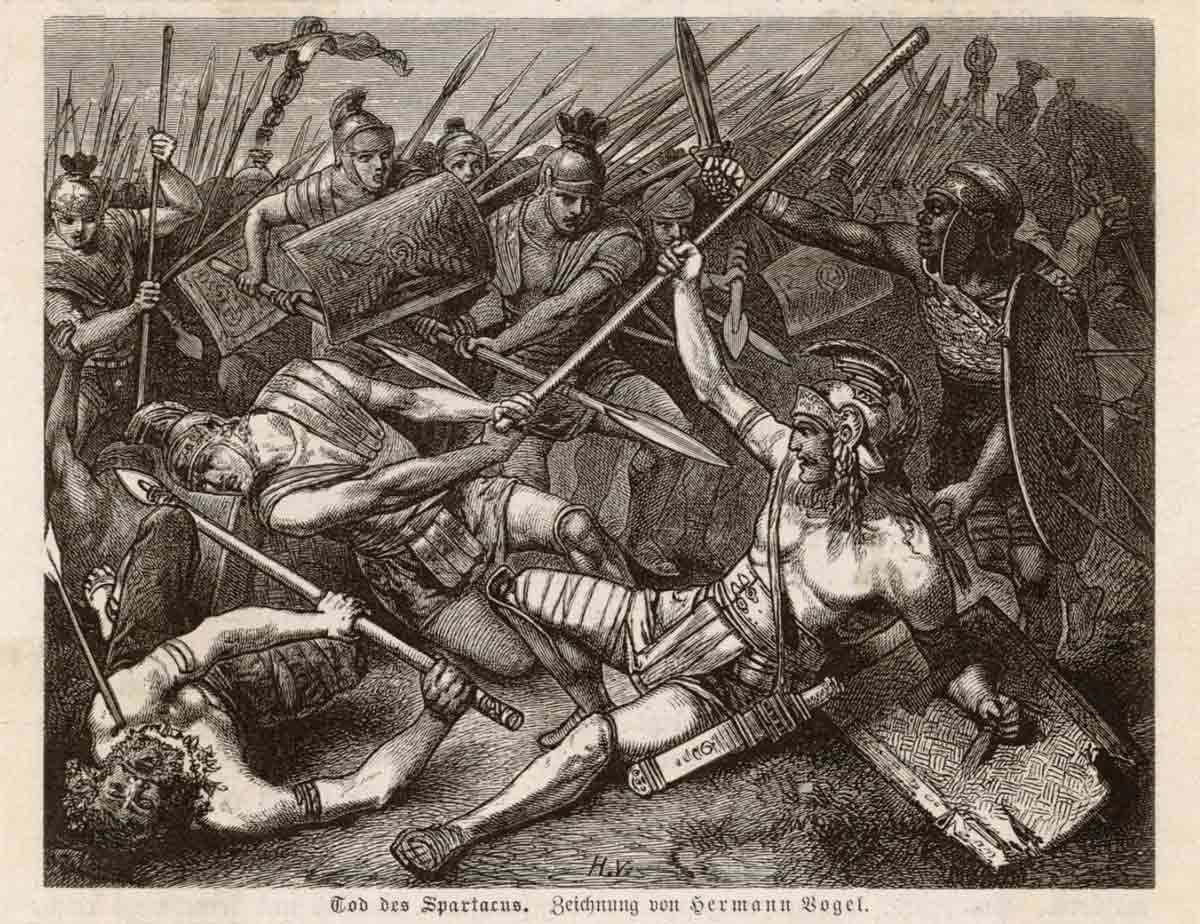

Spartacus is one of the most famous Thracians outside of myth, mainly due to modern representations in television and cinema. After serving as a soldier in the Roman auxiliary, he was forced into slavery and sold to a gladiator school in Capua. In 73 BCE, he incited a riot at the school and escaped using only kitchen utensils with about 78 other gladiators. They managed to secure weapons from a cart on the way to a different gladiatorial school before fleeing the city.

Along with fellow gladiators Oenomaus and Crixus, Spartacus won several encounters against the Roman military despite his limited military experience. He proved to be a competent tactician, gaining more followers and growing his ranks to well over 70,000 people. Though Oenomaus was said to have likely died during one of the first encounters against the Romans, Crixus became the leader of the Gallic and Germanic contingents.

Spartacus and Crixus seem to have disagreed on the goals of the revolt. Though modern sensibilities have attributed to Spartacus the aim of ending the institution of slavery and overthrowing Rome, there is no evidence to suggest that. It was very difficult for people at the time to imagine a world without slaves and there were no sympathy movements that rose up in the wake of Spartacus’ revolt. In all likelihood, he simply wanted an end to his own slavery.

Given his movements, he seems to have been trying to escape across the Alps and go back to Thrace. This goal would not have suited many of his followers, however, many of whom were native pastoralists and cared nothing for Thrace. Crixus himself apparently wanted to begin a career as a brigand in Italy. Despite Spartacus’ attempts to rein in the Gallic leader, Crixus was more interested in plundering and sacking cities, eventually leading his own movement against the Romans where he was defeated and killed at Mt. Garganus.

Spartacus was eventually defeated by Crassus and Pompey, later known as Pompey the Great. Sources say that he died fighting, though his body was never found.

Select Bibliography

Baldwin, B. (1967) “Two Aspects of the Spartacus Slave Revolt,” The Classical Journal, 62(7), 289–294.

Bianchi, U., Horewitz, R., & Girardot, K. S. (1971) “Dualistic Aspects of Thracian Religion,” History of Religions, 10(3), 228–233.

Casson, L. (1977) “The Thracians,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 35(1), 3–6.

Venedikov, I. (1977) “Thrace,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 35(1), 73–80.