Though the ancient Greek and Chinese civilizations are both recognized for their vast cultural impact on the West and the East, respectively, very few imagine that they ever came in contact. However, this is exactly what happened between 104 and 101 BCE, in the confluence of modern-day Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, in Central Asia. It was a contact characterized by diplomacy, exchange, but also violent confrontation. This confrontation was over the fabled “heavenly horses” of the Ferghana Valley and was thus called the War of the Heavenly Horses.

Fool Me Once, Xiongnu: Prelude to the Conflict

While the Roman Republic was slowly expanding its influence across the Mediterranean in the West, in the Far East, across the Iranian plateau, and beyond the Himalayas, existed a vast empire with a well-developed and sophisticated administration, wielding immense cultural and military influence: China under the Han Dynasty.

As was the case for most of China’s long history, China was under constant pressure from a nomadic confederation from the north, the Xiongnu. The Chinese had attempted to achieve peace through tribute and royal marriages, but the raids continued, and so upon the ascension of the seventh Han emperor to the throne, Emperor Wu (156-87 BCE), a different policy was followed: one of military escalation.

Anyone planning to go against a confederation of steppe peoples—and win—would know that a powerful, versatile cavalry is essential, and this, predictably, became the priority of the Han court in this period. Tentative diplomatic contact had been made with the oasis cities of the Tarim Basin (modern day Xinjiang) and beyond, in Bactria and Sogdiana (modern day Afghanistan and Tajikistan). Through these, the Han had learned that the longtime nomadic rivals of the Xiongnu, the nomadic Yuezhi, had established themselves in Bactria, after being forced to flee there by the former. So, in 139 BCE, Emperor Wu dispatched an emissary to the Yuezhi, by the name of Zhang Qian, to form an alliance against their common foe. His account of his travels and (mis-)adventures, preserved by the Chinese chronicler Sima Qian, forms the basis of our knowledge of the War of the Heavenly Horses.

Zhang Qian travelled through the Tarim Basin, and it was there that he must have discovered how powerful the Xiongnu confederation had become: the oasis cities were paying tribute to the nomads, and all the lands between them were under their control. He was soon captured and sold as a slave of the nomads for the next thirteen years. The imperial court must have thought him dead, but his loyalty to the emperor never wavered. He eventually managed to escape and make his way to the Yuezhi, who were now settled in Sogdiana and northern Bactria.

Passing through Ferghana and entering Bactria, he encountered a people of a strange culture that was unknown to him, different from the Saka (Scythians) and Yuezhi overlords to whom they paid tribute. He called them the Dayuan, which is sometimes translated as “the Great Ionians.” They were none other than the remnants of the Greek kingdom of Bactria and of the settlers who had populated the cities founded or conquered by Alexander the Great, two centuries before, conventionally known as the Greco-Bactrians.

The Glory That Was Greece

The kingdom of Bactria, one of the Hellenistic states that rose after Alexander’s conquests, had suffered the nomadic threat for most of its history, much like the Chinese. Indeed, the same historical processes directed the fate of both peoples. The Xiongnu, as mentioned above, had forced the Yuezhi to flee west. As they did, the Yuezhi in turn forced another collection of nomadic peoples, the Saka, to flee south and west, into Bactria. Already weakened by dynastic infighting and civil war, Greek Bactria fell in two successive waves of nomadic invasion, one from the Saka and another from the Yuezhi, who soon followed them there, after 145 BCE.

The Kingdom of Dayuan was most likely a collection of formerly Greco-Bactrian and other oasis cities in Sogdiana and the Ferghana valley, under the authority of local Saka chieftains. Qian describes their lands as fertile, producing rice, wheat, and wine. The people there are mentioned as living in fortified cities, fighting with bows and spears, as well as shooting arrows from horseback. This is likely in reference to mixed armies of Saka horse archers and infantry equipped in the Greek manner.

The only other place Zhang Qian could find a parallel for the Dayuan was the land of “Daxia,” known to us as Bactria. This land, he commented, “…has no great ruler but only a number of petty chiefs ruling the various cities. The people are poor in the use of arms and afraid of battle, but they are clever at commerce.”

By the time Zhang Qian entered Bactria, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom had collapsed, and there was no central power but that of the nomads, with the Greek cities firmly under their sway. The remaining Greco-Bactrian armies and their commanders had fled into India, where they established the Indo-Greek kingdoms, which would last a bit longer, until around 10 CE.

Leaderless and militarily unable to exercise any authority, the remains of the Greco-Bactrians rallied in their cities, some like Alexandria Eschate in Sogdiana, even founded by Alexander himself, and sought protection behind the walls that the nomads could not overrun. A tense relationship developed between the nomadic Saka and Yuezhi, and the settled Greco-Bactrians, whereby the cities grew rich from the trade the nomads facilitated and, in turn, paid those nomads in yearly tribute. The latter progressively adopted more and more elements of Greek culture and gradually assimilated into the settled way of life.

The Allure of the Heavenly Horses

Zhang Qian had arrived in the lands of the Yuezhi too late. They had fled the Xiongnu for a reason and had already begun adopting the settled way of life in northern Bactria. Indeed, in the following centuries, the Yuezhi would go on to found the Great Kushan Empire, spanning Bactria and most of northern India, uniting Greek and Indian culture under the umbrella of Buddhism in their powerful realm. But this was in the future still; for the moment, they were unwilling to aid the Chinese in the fight against the dreaded Xiongnu.

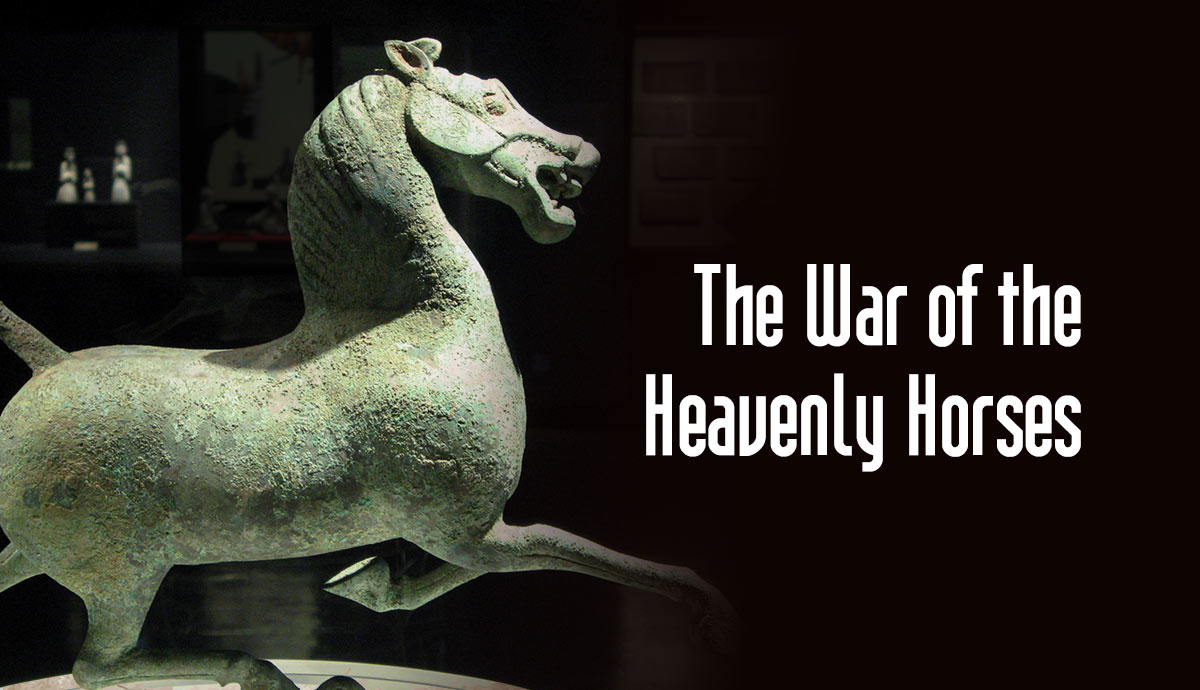

This would have been a disappointment but for what Zhang Qian witnessed on his way to the Yuezhi. In the Kingdom of Dayuan, he reported, more importantly than anything else, could be found “many fine horses which sweat blood,” claiming that “their forebears are supposed to have been foaled from heavenly horses.” This piece of information alone sparked dozens of diplomatic missions back and forth from the Han imperial court and the various cities, statelets, and kingdoms that lay beyond the Tarim basin.

This intensification of diplomatic contacts, however, did not signify good relations and did not provide the Han with the horses they sought. Dayuan and the other cities thought themselves too far from the Han Empire and treated the emissaries of the emperor with contempt, refusing to follow established diplomatic protocol, charging them exorbitantly, or even outright refusing to supply them. Outraged reports flooded the Chinese imperial court, and Emperor Wu, emboldened by recent victories against the Xiongnu, decided to bring these arrogant Westerners to heel.

The Stick and the Carrot: Opening Skirmishes

An army of 20,000 or 30,000 troops was dispatched across the Tarim Basin, forcing the Xiongnu to withdraw before its immensity. The cities did bow in the end, including the Kingdom of Dayuan, but the Chinese had to besiege each of them individually, and due to harsh conditions and over-stretched supply networks, they had lost many men in the process. This did not go unnoticed by the Dayuan.

The matter of the heavenly horses still stood. Envoys of the Han reported that “Dayuan has some fine horses […] but the people keep them hidden and refuse to give any [to them]!” Undeterred and possibly hoping that the lessons of the recent campaign of subjugation were well remembered by the king of Dayuan, likely a Saka chieftain, the emperor dispatched an embassy laden with gold and fittingly, a golden sculpture of a horse, with the sole objective of acquiring the heavenly horses. Dayuan, however, had grown rich and powerful from the commercial networks with the Han and the lessons it had acquired from the preceding hostilities were not the ones Emperor Wu had envisioned.

On the contrary, “the men of the state […] plotted together”—here we can imagine an assembly of Greek-descended nobles in the city of Alexandria Eschate, counselling the Sakan king, “The Han is far away from us and on several occasions has lost men in the salt-water wastes between our country and China. […] if the Han parties go farther north, they will be harassed by the Xiongnu […] if they go to the south they will suffer from lack of water and fodder.” Knowing their lands better than the Chinese, they relied on the simple fact that their enemy would starve long before reaching their walls.

The importance of the heavenly horses for the Dayuan was higher than that of either the gifts or the threats of the Chinese, and so the answer was no. Years of insults, arrogance, and diplomatic faux pas must have piled on. How could these tiny cities, grown wealthy on trade with China, defy the will of their emperor? The envoys cursed the leaders of the Dayuan, and worse still, smashed the golden horse they had brought as a gift to them in the first place. Despite the wrath of the Dayuanese nobles, the Han envoys were allowed to depart but were soon intercepted and killed before leaving the kingdom! There was no going back.

Dayuan and Only: The First Phase of the War

The year 104 BCE saw the first phase of the war, with the Chinese emperor sending a force of 20,000 to 30,000 men, just as before, to punish the Dayuan and acquire the horses. An impressive force though it was, the hopes of Dayuan were confirmed: the expedition was a disaster. City after city closed its gates, refusing to resupply the army and forcing the Chinese general, Li Guangli, to spend precious time and resources besieging them. By the time the army reached the borders of Dayuan in Yucheng, it numbered in the thousands and was decisively defeated there by the Dayuanese forces. As Zhang Qian reports, the army returned to China one or two tenths of its original size.

Emperor Wu was urged by his advisors to abandon the Dayuan endeavor and focus on the Xiongnu instead, but he rightly felt that if it became known that China could not conquer a small country like Dayuan, its reputation—the basis for its successful diplomacy—would suffer greatly and inspire other upstart states into defiance. Therefore, it appears as though the resources of the entire empire were drawn upon for this second punitive expedition. “The whole empire was thrown into a turmoil, relaying orders and providing men and supplies for the attack on Dayuan.” Sima Qian reports.

The Empire Strikes Back: The Second Phase of the War

Hundreds of thousands of men were sent to Dunhuang, also known as the Jade Gate, China’s door to the West, followed by 100,000 oxen, 30,000 horses, and plenty more thousands of donkeys, mules, and camels besides. This vast force was placed under the command of the disgraced Li Guangli, who must have had a personal vendetta against the defiant Dayuan and the other oasis cities of the Tarim Basin.

This time around, most cities submitted, and the one that did not, Luntou, was besieged, razed to the ground, and its population was massacred. This ensured that no further resistance was met until the army reached the capital of the Kingdom of Dayuan. The Dayuanese attempted to meet the Chinese on the battlefield but were overwhelmed and had to retreat behind their walls. A 40-day siege ensued.

Under these dire conditions, and with no victory in sight, the court of the Dayuan fell into infighting. The nobles plotted against the king, Wugua, claiming that it was his hostile policy towards the Han and his refusal to give up the horses that had caused the war. King Wugua was soon assassinated, and his head was brought to General Li Guangli.

The terms set by the Dayuanese nobles were straightforward: if the Chinese promised not to attack them, they would hand over their best horses and supply the army. If they did not agree, they would slaughter the horses so that no one would have them. Worse still, if the Han spent any more time on the siege, reinforcements would arrive from the allied kingdom of Kangju, and they would find themselves surrounded. One could hardly think of a more compelling proposal.

Thus, it was promptly accepted, and the city threw open its gates. The Chinese received three thousand stallions and mares, and a noble by the name of Micai was set up by the Chinese as the new king of Dayuan, as in earlier days he had treated their envoys kindly. Satisfied, laden with gifts, and resupplied, Li Guangli began the long journey home. China’s honor had been restored, and the heavenly horses had been acquired.

A Brave New World: Central Asia in the Aftermath

News of the Chinese victory reverberated among the various cities of the Tarim Basin, and as the army returned home, they willingly provided noble hostages, gifts, and supplies to win Chinese favor. The army arrived in China victorious, and Li Guangli was rewarded handsomely for his service. Back in Dayuan, the new status quo did not last long, and King Micai, seen as a collaborator and a coward, was murdered, and Chanfeng, the brother of the late King Wugua, was given the throne. Despite this, Chanfeng sent his own son as a hostage to the Han court and ensured that he would follow a policy of cooperation and trade.

Despite the initial setbacks, the Han campaign against Dayuan and the War of the Heavenly Horses gained China something much more valuable than its namesake. Cowed by the impressive show of force, the oasis cities came firmly under Chinese influence, garrisons and fortresses were established, and a reliable supply network of farms and grain silos was put in place to facilitate Han military maneuvers.

It became the basis for the establishment of the Chinese Protectorate of the Western Regions, as the borders of the empire reached a new extent. The establishment of control and order, in turn, facilitated the flourishing of overland trade networks, which soon became the lucrative Silk Road. Luxury goods from as far afield as the Roman Empire, as well as scholars, diplomats, and explorers, would make their way back and forth, uniting different parts of Eurasia with each other like never before.

Bibliography

Hansen, V., The Silk Road: A New History, (Oxford: 2012).

Loewe, M., “The Former Han dynasty” in Twitchett, D., Fairbank, J. K. (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Vol. I – The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220, (Cambridge: 2008).

Rong, X., Galambos, I. (trans.), Eighteen lectures on Dunhuang, (Boston: 2013).

Sima Qian, Watson, B. (trans.), Records of the Grand Historian: Han Dynasty II, Revised Edition, (Hong Kong, New York: 1961) – see Chapter 123: The Account of Dayuan.