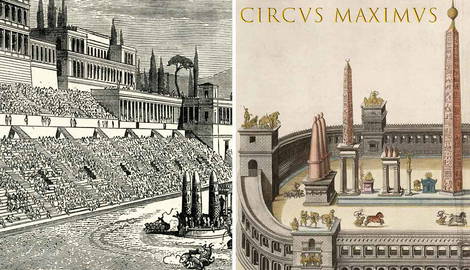

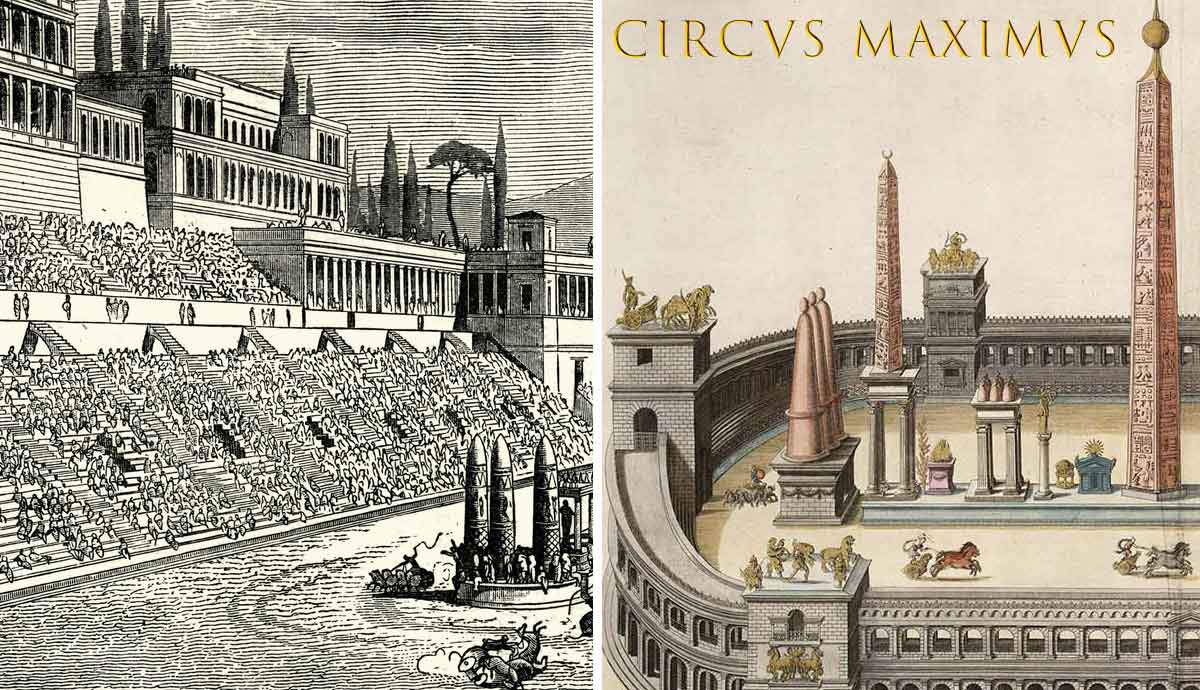

The Circus Maximus was one of ancient Rome’s most iconic structures – a massive race track built for the Roman favorite past time – chariot racing. It was also among the most impressive examples of ancient engineering and architecture. The grand stadium was the largest in the Roman world and could accommodate over 150,000 spectators, while the more famous Colosseum had a capacity for “only” 50,000. Besides being a massive sports arena, the Circus Maximus was the centerpiece of Roman social and political life.

The venue was one of the rare places where the emperor and other high dignitaries could interact with their subjects, show their benevolence and boost popularity by dispensing gifts, monetary rewards, and, most importantly, free food. While little remained of its former splendor, the legacy of the Circus Maximus can still be seen in its impact on modern sports and entertainment.

A Brief History of the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus predates both the Roman Empire and the Roman Republic. Built in the sixth century BCE, during the reign of Tarquinius Priscus, the fifth king of Rome, the first stadium was just a flat sandy area used mainly for religious festivals and ceremonies. The venue was later converted into a race track, with the first chariot races taking place in the fourth century BCE. It did not take long for chariot racing to become the most popular form of entertainment in ancient Rome.

Over the centuries, the Circus Maximus was expanded and renovated. In 329 BCE, the addition of wooden seating and an extended track further increased the capacity of the arena. At the end of the first century BCE, Julius Caesar rebuilt the stadium, adding more seating space. At its peak, during the 1st century CE, the Circus Maximus could contain at least 150,000 spectators.

Chariot Races at Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus, located in the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, was primarily used for chariot races, the favorite pastime of the ancient Romans. The races were held during various festivals and celebrations, often being a highlight of the event. The races were a dangerous sport, and accidents were common, only adding to the excitement for spectators.

The most successful charioteers became highly paid celebrities with legions of adoring fans. They belonged to one of four principal circus factions, each with its colors and symbols: Blues, Greens, Whites and Reds. The emperors themselves were some of the greatest fans, with Emperor Caligula taking particular interest in the races.

Other Sports in the Grand Arena

In addition to chariot races, the Circus Maximus was also used for other sporting events – animal hunts and gladiator fights. The wild beast hunt – venatio – involved large numbers of wild animals, such as lions, tigers, bears, and even elephants, who were chased down by trained hunters or gladiators.

War captives, condemned criminals, or heretics (including early Christians) were also thrown to the beasts (damnatio ad bestias), in this case, with deadly results. Another popular Roman sport – gladiator fights – were also held in the center of the Circus Maximus. Every major Roman city had its “own Circus Maximus,” a large chariot racing venue that was always the most impressive edifice in the town.

Political and Cultural Significance of the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus was an essential part of Roman culture, as it played a significant role in the political and social life of the ancient Romans. The chariot races were more than mere entertainment. They had an important role in imperial politics. The circus factions were often associated with political parties, and powerful political figures used the races to gain support and influence.

As the major patron, the Roman emperor used the chariot races to solidify his position and bolster his popularity. A day at the Circus Maximus was an excellent opportunity for the emperor to interact with his subjects and to dispense gifts, ranging from money to free bread. From Augustus onwards, the emperor was the only one with access to the imperial treasury and the large sums required to maintain the enormous structure and fund the expensive races.

The “New Circus Maximus” – the Hippodrome of Constantinople

Second to Circus Maximus was the Hippodrome in Constantinople, built by emperor Constantine the Great for his brand-new imperial capital. Like the Circus Maximus in Rome, the Hippodrome was also the center of social and political life. The main circus factions, the Blues and Greens, played an important role in imperial politics. However, after the infamous Nika Riots, which almost toppled Emperor Justinian, and following one of the worst massacres of civilians in ancient history at the hands of the soldiers led by General Belisarius, the circus factions lost their political power, retaining only a ceremonial role. The sport’s popularity gradually declined as Byzantine emperors had to divert funds to defend the beleaguered Roman Empire.