Marriage in most historical eras was not necessarily for love but for economic advancement, political alliance, and royal lineage. This was particularly true of the upper classes. In some cultures, a consequence of this was marriages between brothers and sisters. In Ancient Egypt, the union of brother and sister within the royal family was promoted to maintain stability in the dynasty. It guaranteed the continuation of the divinity of the pharaoh and divine balance, Ma’at. In certain cases, the pharaoh even married other relatives, including daughters, to maintain the purity of the family.

Taboo Marriages

In contemporary society, there is still the so-called “incest taboo.” While other types of relationships previously shunned have become more acceptable, the taboo has grown in recent generations, with people less tolerant today than in previous eras. Before the Civil War, marriage between first cousins was legal in all states in the United States. It is now only legal in 18 states, with seven other states requiring certain conditions be met. Sibling unions are universally considered illegal, immoral, and unnatural by Western countries.

Brother-sister marriages, also known as consanguinity or adelphogamy, have nevertheless appeared among cultures throughout the world, including Hawaii up until the 19th century, Japan, Ancient Greece, and perhaps most infamously, the European Habsburgs. These were all cases of extenuating circumstances. In Greece, it was permitted in certain city-states but was still considered an “unholy union.” The Habsburgs practiced it to enact a web of dynastic rule across Europe; as Christians, however, it was still considered fundamentally immoral. Yet the concept of an incest taboo does not seem to have existed at all in the minds of ancient Egyptians, who indeed acknowledged it as a cornerstone of their entire cosmos.

Sacred Marriage Among the Egyptian Gods

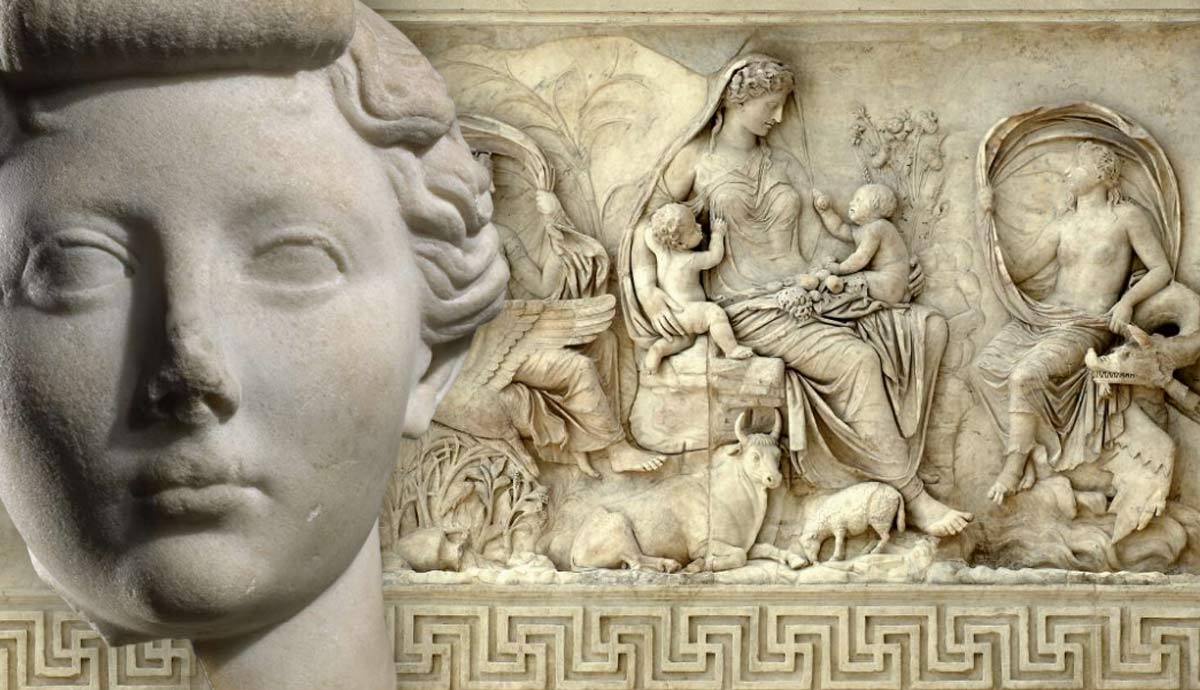

Brother-sister marriage was customary in many ancient mythologies. Often called the Hieros Gamos, or sacred marriage, it symbolized the necessary union between cosmic forces, such as Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture) or Geb (earth) and Nut (heaven) in Egyptian religion, or Gaia (earth) and Ouranos (heaven) in Greek religion. In most mythologies, this was simply a logical necessity considering the limited available partners in heaven.

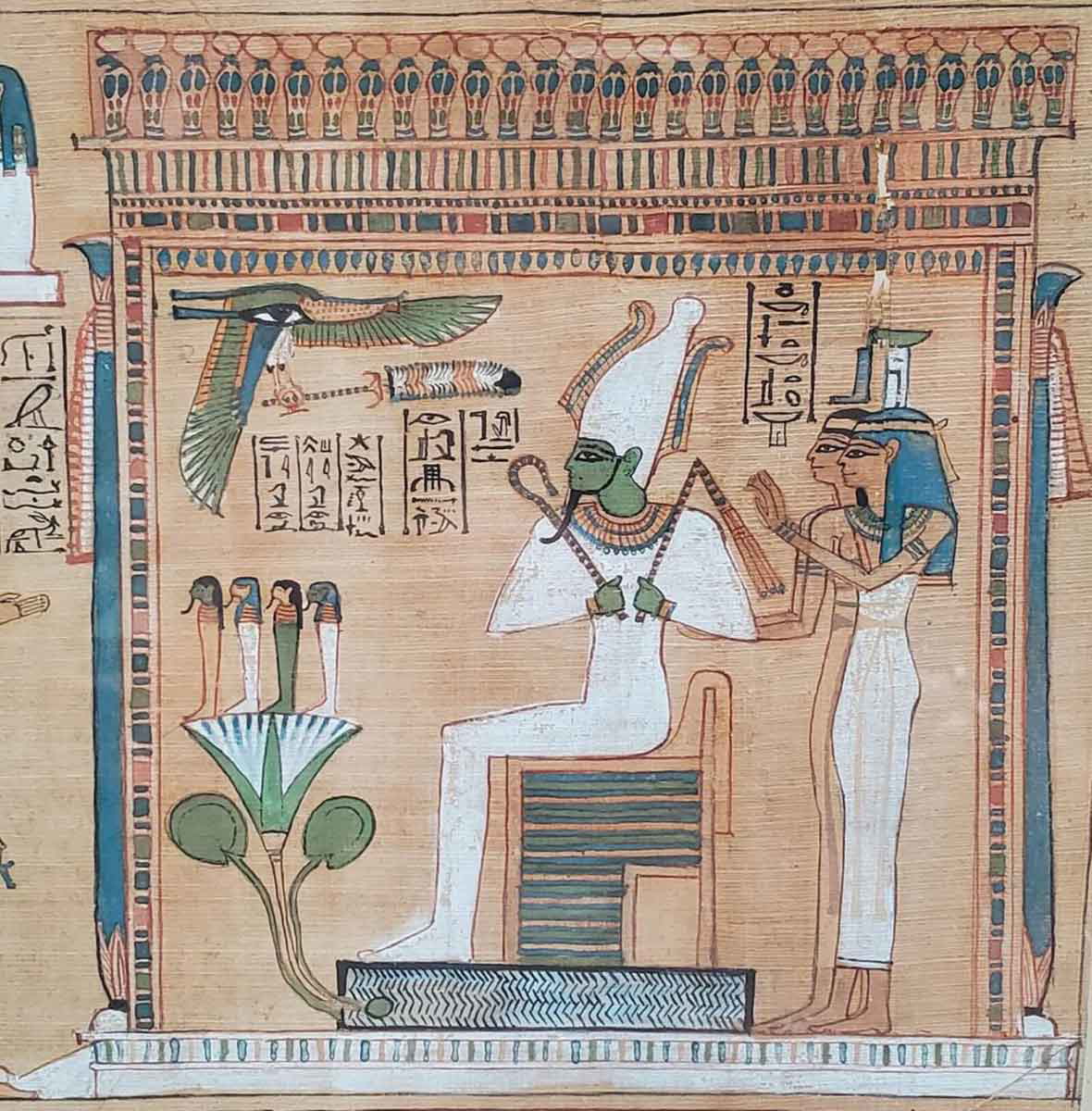

Religion in Egypt, despite the shared reality of limited mates, viewed the brother-sister relationship more intimately. Descriptions display love and intimacy and act as inspiration for earthly couplings. The best example is the brother-sister pairing of Osiris and Isis. As the god of the Nile and fertility, Osiris reflected the wealth of Egyptian farms and the food they produced. His sister-wife, Isis, was the goddess of magic and fertility, who joined her powers with her husband to help Egypt prosper. When Osiris was killed by his jealous brother Set (himself often paired with their other sister, Nephthys) and his body parts spread throughout Egypt, Isis journeyed across the land to retrieve them. She then used her powers to return him to life, mating with him and birthing their son, Horus, the divine essence of the pharaoh. To honor these gods, pharaohs would often follow Osiris’ example of marrying their sister.

Old Kingdom Origins

The Old Kingdom was the age of pyramid building. It also saw the earliest conclusive evidence of the practice among royalty. However, the earlier 1st dynasty pharaoh Djet’s wife, Merneith, was also very likely his sister.

The 6th dynasty pharaoh Pepi II was legendary for his 94-year reign (though many historians believe it was closer to 67 years). He was less famously known for marriages to various relatives, including his sister, Ankhesenpepi III, and to Neith and Iput II, half-sisters or aunts, depending on which earlier pharaoh was their father. Whatever her relation to Pepi II, Neith gave birth to his son and successor, Merenre Nemtyemsaf II.

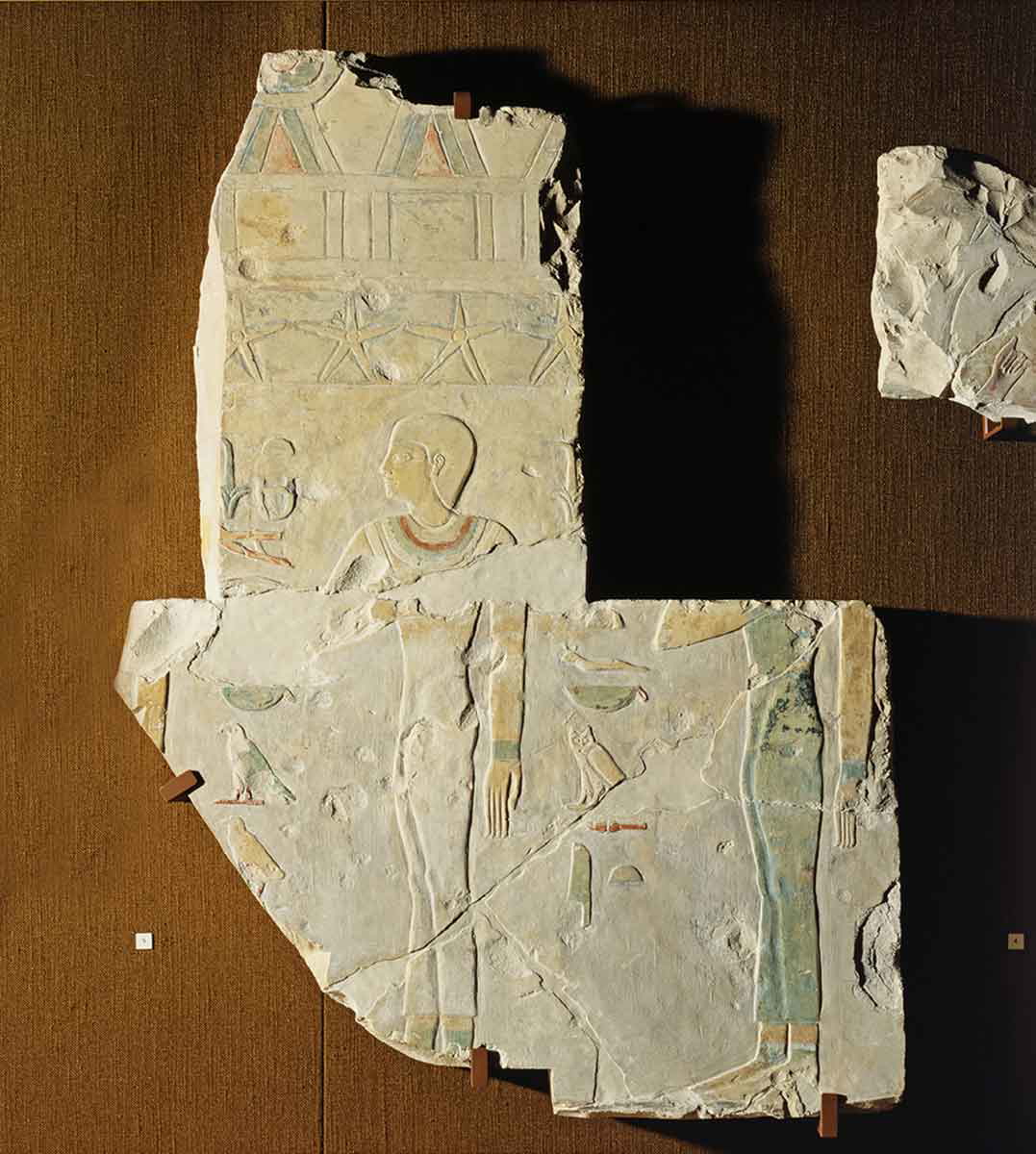

The 4th dynasty pharaoh, Khufu, builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza, may have married his half-sister, Meritites I, who was possibly a daughter of Khufu’s father, Sneferu. Khufu’s son, Khafre, builder of the second pyramid and the Great Sphinx, married a niece, Meresankh III, who had multiple sons and daughters with her uncle-husband. Another of Khafre’s wives, Khamerernebty I, may have been a half-sister and was the mother of Menkaure, the builder of the smallest pyramid at Giza. Menkaure then married his full sister, Khamerernebty II. She produced a son with her brother who apparently died during his father’s reign.

The 4th dynasty included the most powerful kings of the Old Kingdom. During this era, pharaohs consolidated power to ensure their success as rulers. Consanguinity played a role in ensuring the continuity of power. As the gods in heaven mingled amongst each other, so too did the royal family.

Middle Kingdom Mingling

Pharaohs in the Middle Kingdom, an often-overlooked period in Egyptian history, also practiced consanguinity. One of the chief consorts of Mentuhotep II, the founder of the era, was his sister, Neferu. However, there was no indication she bore him children. Yet some 150 years later, Senusret II married at least two (possibly all four) of his sisters, one of whom, Khenemetneferhedjet I, gave birth to his son and successor, Senusret III, one of the greatest pharaohs of the era. Finally, the first definitively known female pharaoh, Sobekneferu, the last ruler of the 12th dynasty, was possibly married to her brother, Amenemhat IV, as she succeeded him following his death.

There also seem to be several examples of brother-sister marriages among commoners during the Middle Kingdom. However, they were still among the higher class. One was a vizier, a chief advisor to the pharaoh, and another was a priest. Such close connections to royalty may have afforded them the practice, or it may have been socially acceptable across the board and simply recorded more frequently among the upper class, as with anything else. Then again, many Egyptologists do not agree that these are legitimate cases. The consensus is still that it was a royal practice not extended to the general populace.

New Kingdom Climax

The majority of brother-sister unions among royalty appear later in Egyptian history, where it seems to have been more customary than in earlier eras. The New Kingdom is universally considered the pinnacle of Egyptian history, with culture, art, and both domestic and foreign power at its peak. It is also the peak of consanguinity. Nearly all pharaohs throughout the 250-year-long 18th dynasty married sisters or half-sisters, including Ahmose I, Amenhotep I, and all the Thutmoses (I-IV). Most famous in this case was the union of Thutmose II and Hatshepsut, both of whom became pharaohs. Their marriage produced a daughter, Neferure. While some scholars suggest she married her half-brother, Thutmose III, in keeping with tradition, the evidence remains unclear.

The difficulty in fully establishing the specifics of familial connections among Egyptian royalty is never more evident than at the end of the dynasty with the family of Akhenaten. Married to Nefertiti, historically seen as a foreigner (her name meaning “the beautiful one has come”), she was almost certainly native Egyptian, and consanguinity may continue here as well. Some scholars suggest a possible brother-sister union, but Aidan Dodson argues Akhenaten and Nefertiti were first cousins, Nefertiti’s father, Ay, being the brother of Akhenaten’s mother, Queen Tiye.

The enigma of the Amarna Age continues with Meritaten, Akhenaten’s daughter by Nefertiti, who was married to the shadowy pharaoh Smenkhkare, Akhenaten’s co-regent. He was possibly Meritaten’s brother if he was Akhenaten’s son. But more likely, he was Akhenaten’s younger brother, making Meritaten his niece. However, Zahi Hawass suggests that Smenkhkare was Nefertiti in the form of the pharaoh. If this is the case, Nefertiti then raised her daughter to the status of wife once she ascended to kingship. Still others suggest Meritaten herself was Smenkhkare, meaning the princess could have been married to her brother, her uncle, her mother, or herself!

This does not even consider the equally shadowy pharaoh Neferneferuaten, almost certainly a female and likely Nefertiti herself, who ruled in her own right following her husband’s death. The confusion is extensive, as whether Smenkhkare and Neferneferutaten were the same person, Neferneferuaten and Nefertiti were the same person, or who Meritaten was married to remains a mystery. Regardless of the specifics, it is quite evident the princess was married to some close relative in her family.

The brother-sister marriage continued with the most famous pharaoh of the age, Tutankhamun, who married his sister, Ankhesenamun. Both children of Akhenaten, recent genetic evidence suggests Nefertiti, who was certainly Ankhesenamun’s mother, may also be the mother of Tutankhamun, making them full siblings. Once married, they tried to continue the line, but nature decided otherwise. Ankhesenamun suffered two miscarriages, effectively ending the 18th dynasty lineage of royal blood.

Brother-sister unions were therefore the norm in the 18th dynasty. Again, the intent was to keep the bloodline pure, but with nearly three centuries of inbreeding, carrying a child to term became less and less likely, culminating in Tut’s failure to procreate. Additionally, there is a strong probability that he suffered from genetic abnormalities resulting from the continuous consanguinity.

Whether these unions always led to offspring, or were intended to, is debated. However, still more shocking to modern audiences would be the union of Amenhotep III and his daughters, Sitamun and Iset. Father-daughter marriage was not common, but evidently acceptable, perhaps in instances where the sister or another close female relative had died. In the case of Rameses II, the most powerful of pharaohs, he married three daughters, Bintanath, Meritamun, and Nebettawy, the first of whom had a daughter by her father.

Consanguinity persisted into the later dynasties but did not always work to the pharaoh’s benefit, as in the case of Rameses III of the 20th dynasty. Considered the “last great pharaoh” of Egypt, Rameses III was a victim of jealous rivalry between wives. Tiye, a lesser wife, was envious of Tyti, Rameses’ sister-wife and the mother to his successor, Rameses IV. Tiye orchestrated an assassination plot to push her son, Pentaweret, to the throne. The plan succeeded in killing the pharaoh, but Pentawaret (and presumably Tiye) were executed or forced to commit suicide.

A later union was more successful and appropriate. Psusennes I of the 21st dynasty married his half-sister, Mutnedjmet, which created a bond of legitimacy for the new pharaoh. Both were children of Pinedjem, a high priest who had previously (and perhaps unlawfully) declared himself pharaoh. Munedjmet’s mother was the daughter of Rameses XI from the preceding dynasty. By marrying her, Psusennes declared his right to rule through the lineage of the Ramesside dynasties.

Ptolemaic Pairings

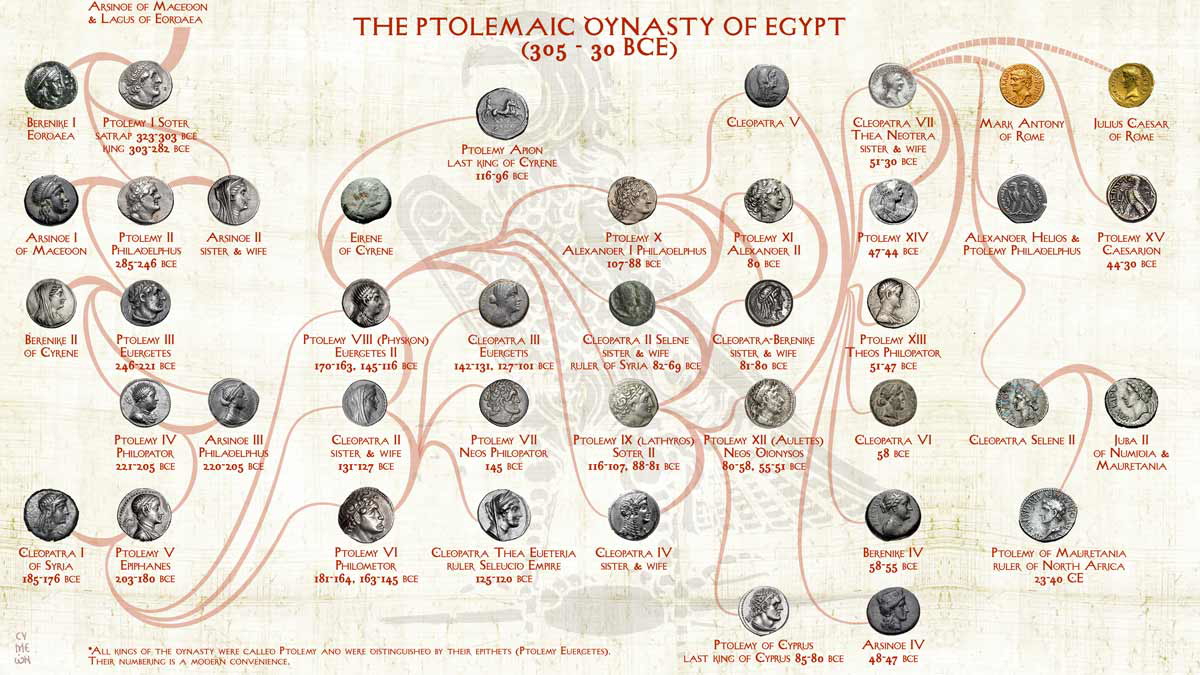

With the conquests of Alexander the Great, Egypt fell under the control of the Greeks. This era became known as the Ptolemaic Period after one of Alexander’s generals, Ptolemy I, took control following the conqueror’s death. Ptolemy immediately elected to adopt many Egyptian customs. One of these was adelphogamy, the Greek word for marriage between siblings. Yet the brother-sister unions among the Greek pharaohs were far more outrageous than their Egyptian predecessors. Contemporary and later critics pointed to this intermarriage and inbreeding as a factor in why the practice was so fundamentally wrong. To keep up with the family drama, one has to remember the repetitive nature of the male name in Ptolemy and the female names as Cleopatra and Arsinoe.

Beginning with Ptolemy II Philadelphos (meaning “sibling-lover”), most Greek pharaohs married their full sister, in his case, Arsinoe II. No evidence suggests they had children, but two generations later, Arsinoe III bore Ptolemy V to her full brother, Ptolemy IV.

Ptolemy V’s daughter, Cleopatra II, married two brothers, Ptolemy VI, giving him four children, and (after VI’s death) Ptolemy VIII, who then later married his niece and stepdaughter, Cleopatra III, though her mother was still reigning. Thus, Ptolemy had two queens, both called Cleopatra, and both immediate family members.

After giving him five children, Cleopatra III succeeded Ptolemy VIII as ruler in her own right, though her reign was marked by a scandalous power struggle among the family. For one, she fought with her mother for power, and ultimately won, Cleopatra II disappearing from the historical record. Later, she raised her elder son, Ptolemy IX, to power as co-regent, though she preferred her younger son, Ptolemy X. The Egyptian army disagreed and forced her to choose the elder. She then fought against him, defeating him in battle in 102 BCE before being ousted and murdered by her “favorite” son, Ptolemy X, who was then defeated in turn by his older brother.

Ptolemy IX might be the consanguinity champion of the era. After serving as co-regent and uniting with his mother, he married his sister, Cleopatra IV, with whom he was in love, and they had several children. Ptolemy then divorced her for another sister, Cleopatra V Selene, though this was forced by their mother, Cleopatra III, who hated her eldest daughter (the IV). Finally, Ptolemy IX possibly married his daughter, Berenice III, though to be fair, it was not a true marriage. Rather, her father raised her to co-regency to ensure succession. Berenice might be the one to compete with him, as she “married” her father (Ptolemy IX), her uncle (Ptolemy X) and, to top it off, her son, (Ptolemy XI).

The end of the convoluted dynasty came with the infamous Cleopatra VII, daughter of the brother-sister union of Ptolemy XII and Cleopatra VI (who may have been the same as Cleopatra V). The last Cleopatra married both her younger brothers, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV, though not simultaneously. Cleopatra was ultimately responsible for both their deaths to solidify her own rule with the help of Julius Caesar. Following her reign, Augustus brought what Romans considered to be a merciful end to the disturbing machinations of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Why Was Brother-Sister Marriage Important in Ancient Egypt?

As previously noted, brother-sister marriages in Egyptian society seem to have been reserved for royalty, or at least the upper echelons. Few examples among the general population are evident, and those that are recorded are debated. They may be cases of different individuals with common names (like a contemporary couple who both have a father named Michael). Certainly, cousin marriage existed in smaller villages, but sibling unions were likely restricted to the realm of the pharaoh and his family to reflect their divine heritage.

A further explanation for consanguinity is another matter debated among Egyptologists. Some interpret that the bloodline, while passing from father to son, also passed through the daughter. At least, divine “power” was channeled through women in the sense that they were vessels of magical authority, seen in Isis as the goddess incarnate. Thus, for the son to succeed his father, he must marry his sister to attain the bloodline and divine status. As a god, any child the pharaoh has would be divine, but one with his sister would be doubly divine.

The importance of female authority can also explain many statues that depict wives, as seen with the Menkaure and his sister-queen, Khamerernebty, holding onto the husband’s arm. She is seen as his guide, transferring her “power” (as Isis did to Osiris) to allow him to rule. He is the ruler; she is the vessel. As many cultures in the world still attest, the man is seen as the head while the woman is the neck, guiding (and even controlling) the movements.

Unfortunately, these theories cannot explain why pharaohs had children with non-relatives, including foreign princesses, concubines, and slaves. If the heir to the throne was supposed to be pure royal blood, why was it acceptable and even customary to elevate “half-common” heirs to pharaonic status? Suggestions have been offered that, since pharaohs had multiple wives, a sister could serve as the ceremonial wife while others were meant to be those with which the pharaoh mated. However, this theory also fails due to the clear evidence of offspring from these pairings. It seems to be a personal preference of the pharaoh (a living god that nobody would dare question).

Finally, a more practical theory is the reality that by marrying into the family, property is not split amongst outsiders. In Egypt, daughters could inherit, so by marrying one’s sister, the pharaoh, noble, or even commoner, keeps his father’s estate intact. While vast studies have focused on the mystical and religious natures of these unions, it could have been a simple case of men wanting to keep their property.

Regardless of the reasoning, consanguinity or adelphogamy was a common practice among Egyptian royalty. While the incest taboo is greater than ever today, it did not exist to them. It should be remembered that the Egyptians would not have understood the genetic issues that arise from sibling marriages. Such knowledge was beyond them, and even if offspring did exhibit abnormalities, it would have been downplayed or outright ignored by the Egyptians themselves. Living gods were meant to be perfect physical specimens.