Among the female pharaohs of ancient Egypt, the most powerful was Hatshepsut. Her reign saw Egypt prosper like never before. Yet Hatshepsut lacks the lasting fame of Nefertiti, known for her beauty, or Cleopatra, known for her machinations. This is because Hatshepsut’s reign was erased by her successors in the practice of damnatio memoriae. It is often claimed that this was the result of her gender, but her crime was even more offensive! She broke Ma’at, the balance of order in the universe, by taking what was not hers.

Hatshepsut: From Queen Regent to Queen Regnant

When Hatshepsut came to the throne in the 15th century BCE, she was the legitimate queen regent, meaning she acted on behalf of the rightful king. In this case, the rightful king was a 2-year-old, Thutmose III. As the child’s stepmother, it was customary for her to step into that role. She was not the first queen regent, nor would she be the last.

Mothers, stepmothers, and grandmothers typically served this role for god-kings too young to make decisions on their own. However, they were expected to remain in the background, making it known that the true decision-maker was the living god on the throne. Yet Hatshepsut came to the realization that she would serve as a better ruler than an infant. Within a few years, she promoted herself from queen regent to queen regnant, no longer governing on behalf of a young king but reigning queen of Egypt in her own right.

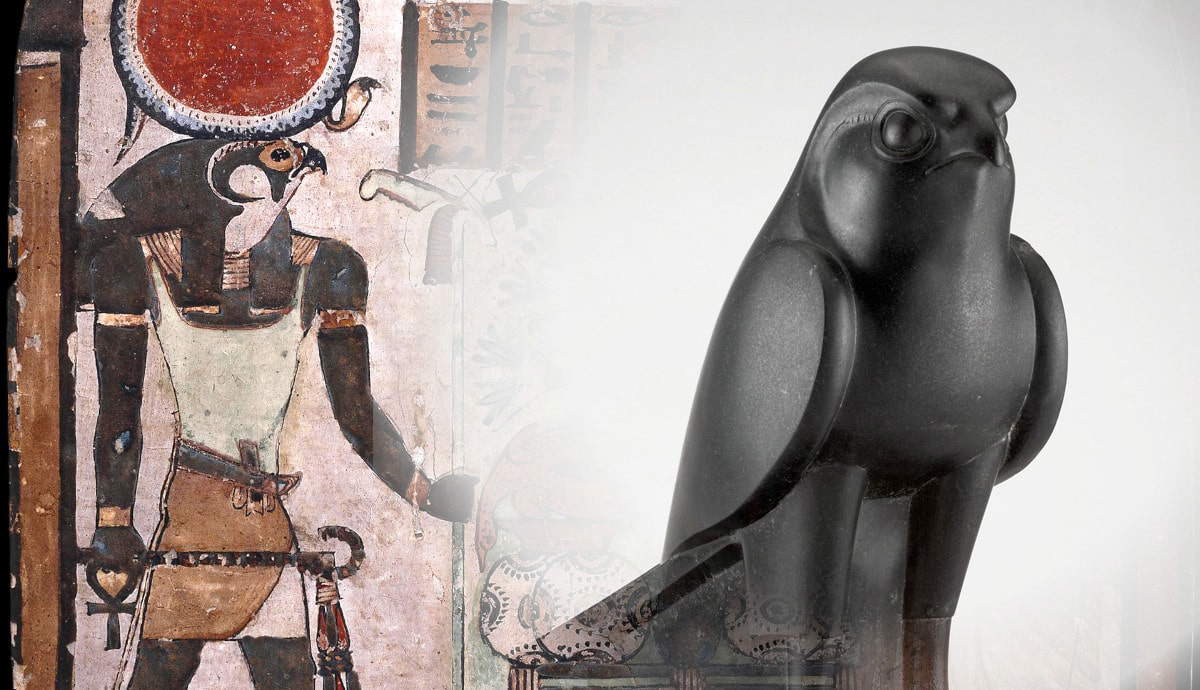

However, it is important to understand the context of language. The term “queen” did not exist in the Egyptian language. The words for “king” were plentiful. The title nswt-bjtj referred to the Sedge and the Bee, symbols of kingship from early dynastic times. Also, the so-called “Horus name,” a name inscribed within a serekh topped with an image of the Horus falcon. By Hatshepsut’s time, the most famous title was per-aa, meaning “great house,” today transcribed as pharaoh. Thus, Hatshepsut could never have technically used a title like queen. While married to the previous pharaoh, Thutmose II, she was called “Great Royal Wife.” Now a widow, she could no longer use that title. Therefore, to ensure her leadership, she decided that the only acceptable choice was to claim herself king, which she did in the seventh year of the reign of Thutmose III, c. 1472 BCE.

From Pharaoh to Heretic

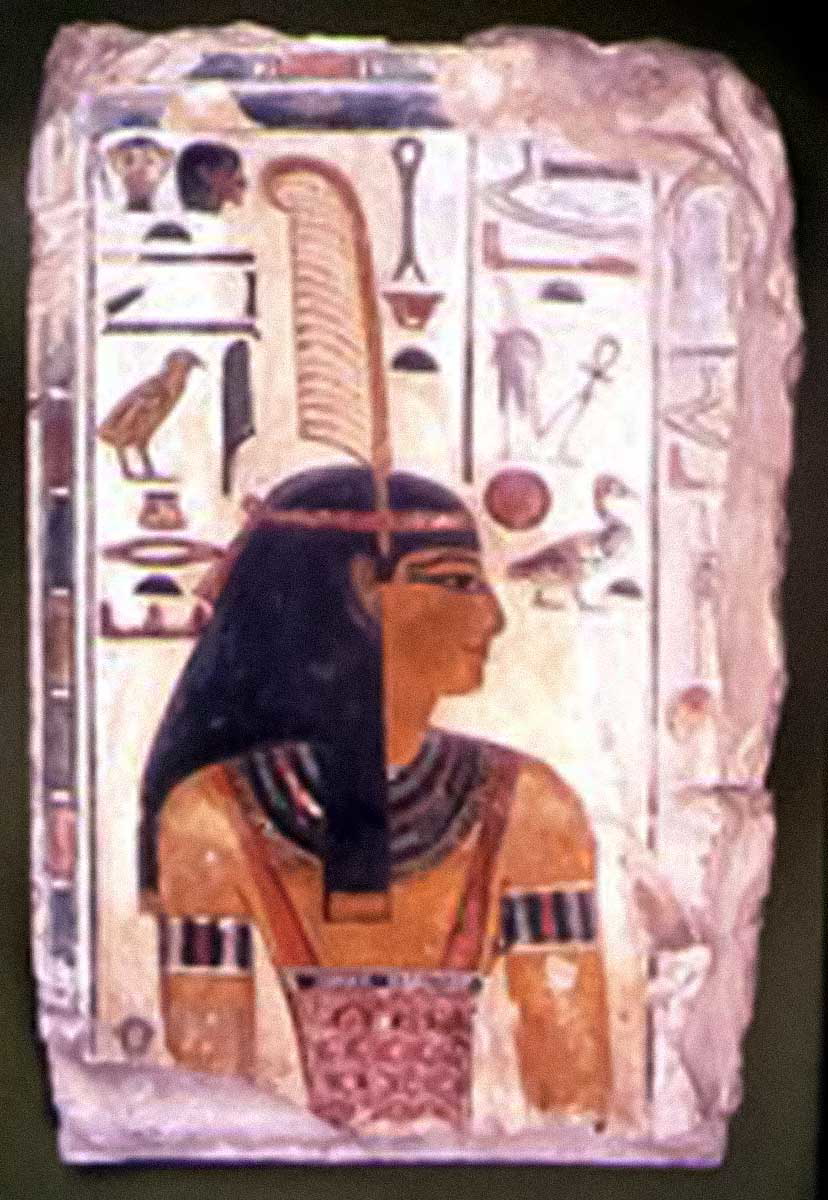

In the eyes of Hatshepsut, this move seemed to her necessary to ensure efficient leadership. Unfortunately for her, in the eyes of the Egyptians, this was sacrilege. She had stepped over the line of cosmic order, called Ma’at in the Egyptian language. Ma’at was the concept that kept the universe in balance, something that pharaohs had upheld since the beginning of Egyptian civilization. Often depicted as a goddess with an ostrich feather on her head and sometimes with wings, she was the daughter of Ra, the great sun god, who ensured his daughter kept order in the cosmos. Ma’at was truth. Ma’at was justice. Ma’at was the Egyptian way. Gods maintained Ma’at in the heavens, and kings maintained Ma’at on earth. Now, this usurper had broken the delicate balance of truth and order in the cosmos.

There had been at least one female pharaoh before, so while certainly uncommon, it was not unprecedented. However, there are two points to consider. First, how much did the common Egyptian know about their own history? This previous female ruler reigned over three centuries earlier. Would the average Egyptian farmer, laborer, or merchant have any notion of this? Second, there had been no alternative before; no royal male was in line to attain the throne in that instance. Again, women having power and authority in Egypt was not unheard of, but taking power from the rightful king was surely unforgivable.

From Heretic to Goddess

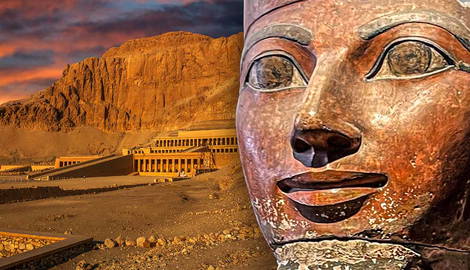

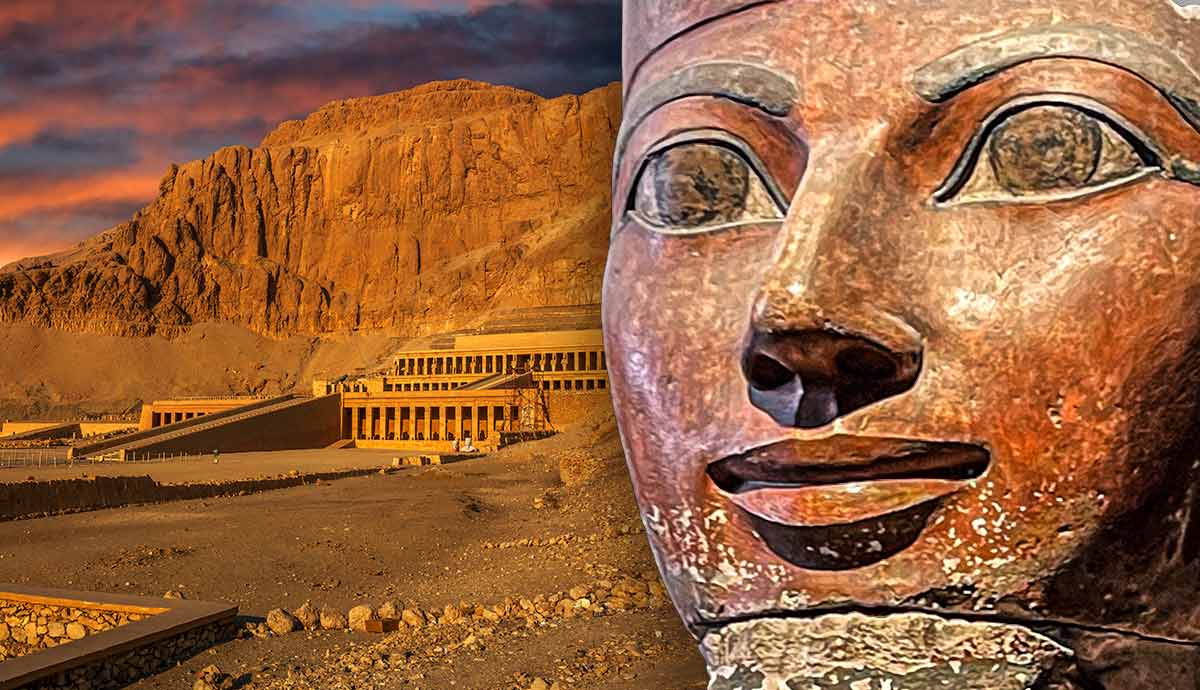

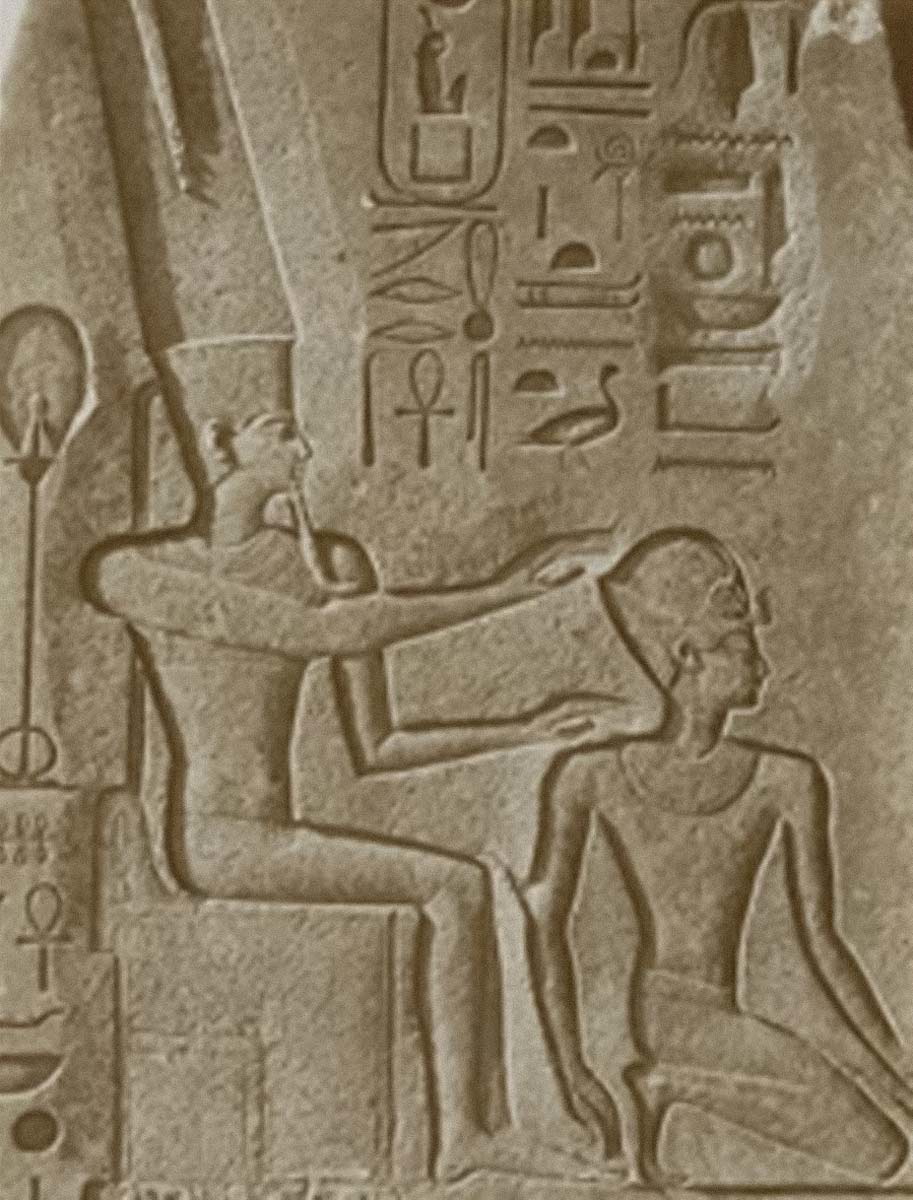

To address this heretical act, Hatshepsut claimed herself not only as pharaoh but as the literal daughter of Amun, the king of the gods during the New Kingdom in Egypt. Pharaohs had historically been viewed as the sons of Ra but were understood to be born of human kings and their consorts. However, Hatshepsut claimed her mother, Queen Ahmose, had been divinely impregnated by Amun. She went as far as to inscribe these claims on her mortuary temple, the Djeser-Djeseru, at the site of Deir el-Bahari.

On the walls of this enormous complex dedicated to herself, the female pharaoh stated that Amun named her “the king who takes possession of the diadem on the Throne of Horus.” Furthermore, she took the name Maatkare, meaning “cosmic order is the soul of Ra.” Thus, her opponents were stripped of their complaints. The most powerful deities in Egypt approved of Hatshepsut’s reign, and to deny her, a goddess, would be denying Ma’at itself.

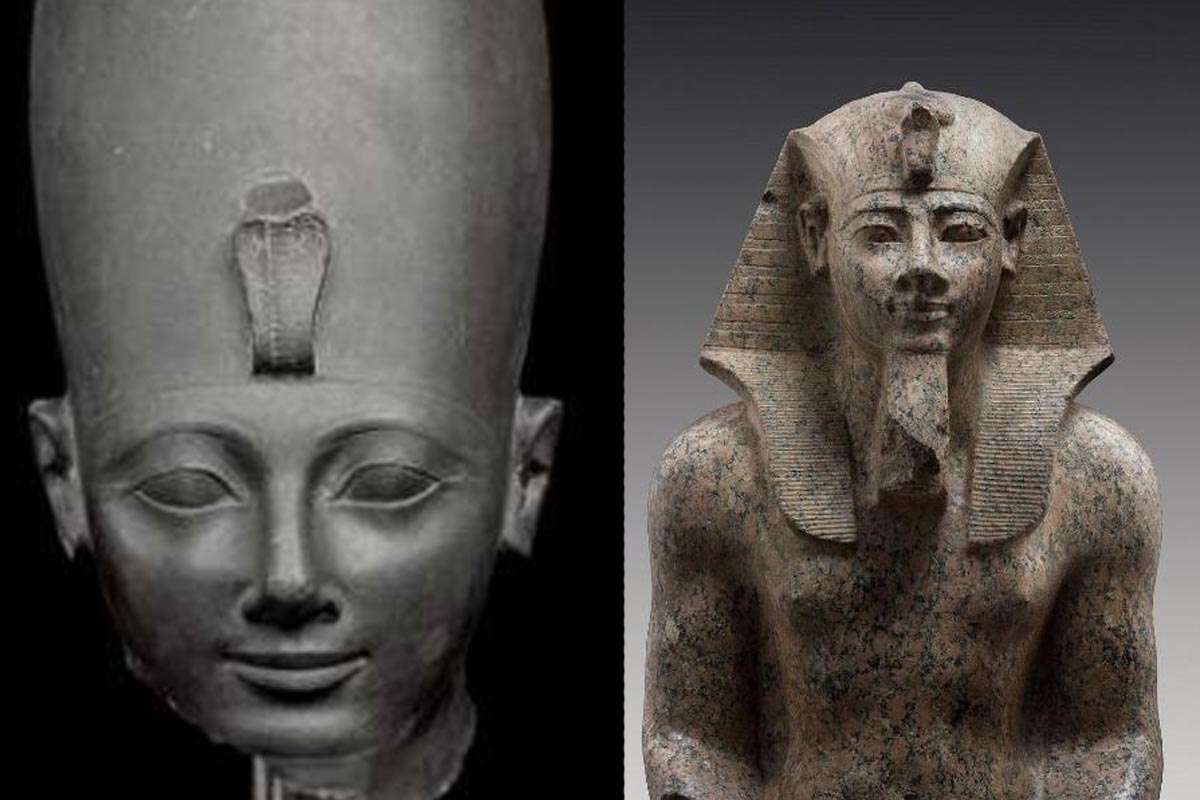

Legitimate ruler or not, Hatshepsut was a shrewd and successful politician. She also promoted herself as a masculine ruler by wearing the traditional false beard of pharaohs, painting herself red in the traditional manner of males, and even depicting herself as the mummified god, Osiris.

Despite her claim of divinity, this female pharaoh was as mortal as those she ruled. After reigning for 22 years, Hatshepsut succumbed to illness, probably bone cancer caused by the carcinogenic substance benzoapyrene found in a skin cream she used. Suffering from diabetes, arthritis, and eczema in her last days, the daughter of Amun seemed anything but a goddess. Still, her reign of 22 years proved effective. She increased her kingdom’s wealth, promoted building programs that ensured jobs for the people, and secured prosperity greater than Egypt had seen since perhaps the Old Kingdom.

A Reign Forgotten

Though Hatshepsut claimed Amun had installed her on the throne, her reign was still erased from history by her successors. While there is no archaeological evidence that she was murdered or that a revolt occurred during her reign, likenesses of her, including statues, reliefs, and monuments, were defaced in the practice of damnatio memoriae. This term dates from the Roman Empire, as emperors were often erased from history by successors who found their rules offensive or displeasing. However, the practice is far older and was common in Egyptian times.

Images depicting Hatshepsut as queen regent were typically left alone, including those that portrayed Hatshepsut alongside Thutmose III as a child. Representations depicting her as king were broken, scratched out, and, in the case of an obelisk she erected at the temple of Karnak, walled up. It was clear: being a queen regent was acceptable, but being the pharaoh was not.

A Name Erased

Curiously, the eradication of Hatshepsut’s name as pharaoh did not take place until 25 years after she died in c. 1458 BCE. Thutmose III, the infant cast aside in the name of his stepmother, is often blamed for this damnatio memoriae. Yet a more logical claim would be that his son, Amenhotep II, made the call.

Near the end of his reign, Thutmose seemingly elevated his son to co-regency, which was technically what Tuthmose experienced with Hatshepsut, to ensure a smooth transition of power. While the dates are not perfect, the destruction of Hatshepsut’s monuments appears to have begun around 1432 BCE, and Amenhotep was co-regent around 1427 BCE. This demands a reevaluation of Thutmose seeking vengeance against his stepmother.

Amenhotep was the likely culprit, not only to ensure he was the rightful heir but also, more importantly, to ensure he upheld the concept of Ma’at. This was not an attack against Hatshepsut for being a woman but a systematic erasure of her actions as pharaoh to ensure the continuity of cosmic order was maintained.

Hatshepsut’s Legacy Remembered

Hatshepsut was neither the first nor the last female pharaoh. The former honor goes to Sobekneferu, who ruled during the 12th dynasty in the 19th century BCE. Some historians even suggest the first female pharaoh was Queen Merneith, who reigned during the 1st dynasty around 3000 BCE, though the consensus is that she apparently happily served as queen regent of her young son rather than as pharaoh. The last was the infamous Cleopatra VII, a Macedonian-Greek ruler who died in the year 30 BCE.

Indeed, Hatshepsut cannot even enjoy the claim of being the most famous woman in Egypt thanks to Cleopatra and another infamous possible female pharaoh, Nefertiti. If one were to poll a typical college classroom today and ask, “when you think of Egypt, what names come to mind,” rarely is the name of Hatshepsut spoken. Her successors did their job well.

Nevertheless, her legacy should not be forgotten, as despite her being a usurper who seized the throne from the legitimate toddler-king, Hatshepsut accomplished more in her reign than most of her predecessors. She initiated trading expeditions to far-off lands, including the land of Punt, somewhere along the Horn of Africa. This brought increased wealth, exotic goods, and cultural exchange to areas previously ignored by Egyptians. She built more monuments than any other pharaoh before her, including sections of the great Temple of Karnak. While parts of it were constructed earlier during the Middle Kingdom, Hatshepsut expanded the complex during her reign. She ensured peace and prosperity throughout Egypt that would last for centuries after her death.

One could argue that Thutmose III had as much success as he did because of his stepmother. The legacies of the greatest pharaohs, Amenhotep III, Ramesses II, and Ramesses III, all see influence from Hatshepsut in their reigns. Even Alexander the Great, who claimed himself as the son of Amun during his sojourn in Egypt over a thousand years later, followed in the footsteps of Hatshepsut’s divinity claims.

Hatshepsut broke the concept of Ma’at, upsetting the established order of the universe. Her reign was erased as a result, but her legacy was not truly forgotten. While perhaps not Egypt’s most famous woman, she is without question its most significant.