In addition to his superhuman strength and knack for achieving the impossible, the legendary hero Heracles was known for his incredible libido. Heracles is said to have fathered numerous children as he traveled the ancient world, battling monsters, conquering armies, and outsmarting gods and Kings. These children and their descendants became known as the Heracleidae, “the children of Heracles.” While some achieved greatness, others only survived as names on a list in their father’s biography. Discover more about the children of Heracles and their impact on mythology and ancient history.

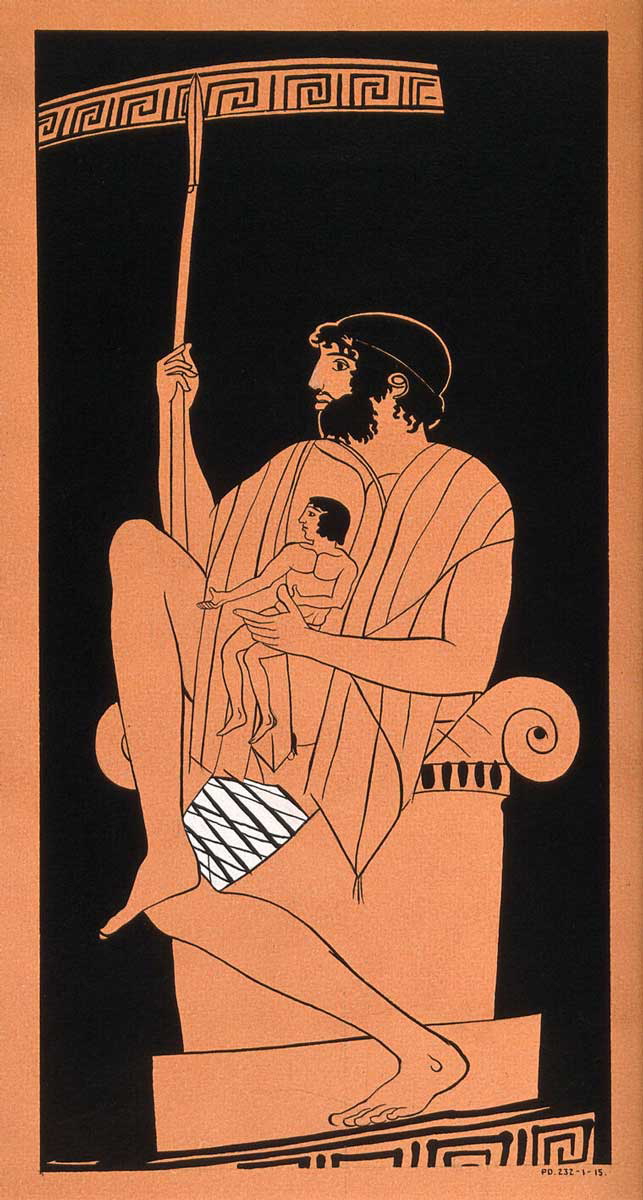

Daughters of Thespius

Heracles‘s first and perhaps most remarkable feat of procreation occurred when he was ordered to slay the monstrous Lion of Cithaeron at just 18 years of age. The lion emerged near Mount Cithaeron and began devouring the cattle belonging to his adoptive father, Amphitryon, and King Thespius of Thespiae. Thespius offered to host Heracles, who hunted the lion for 49 days and defeated the beast on the 50th day.

In Thespia, killing the lion was not Heracles’s most impressive feat. As a reward for his services, Thespius sent one of his 50 daughters to sleep with Heracles each night that he hunted the lion. Each daughter became pregnant and gave birth to a son. In some versions, Heracles slept with all the daughters in one night; the oldest and youngest daughters each gave birth to twins. There were only 49 sons in another account, as one of the daughters refused to sleep with Heracles. As a result, she was punished by becoming a virgin priestess at the sanctuary of Heracles in Thespiae.

Thespius’s grandsons did not achieve the same fame as their father. As is the case with nearly all his children, Heracles did not play an active role in the lives of his 50 sons in Thespiae. The only involvement Heracles had was sending a message to King Thespius years later, after his labors. He instructed the King to keep seven of his sons in Thespiae, send three to Thebes, and have the remaining 40 accompany Heracles’s friend Iolaus to establish a colony on the island of Sardinia.

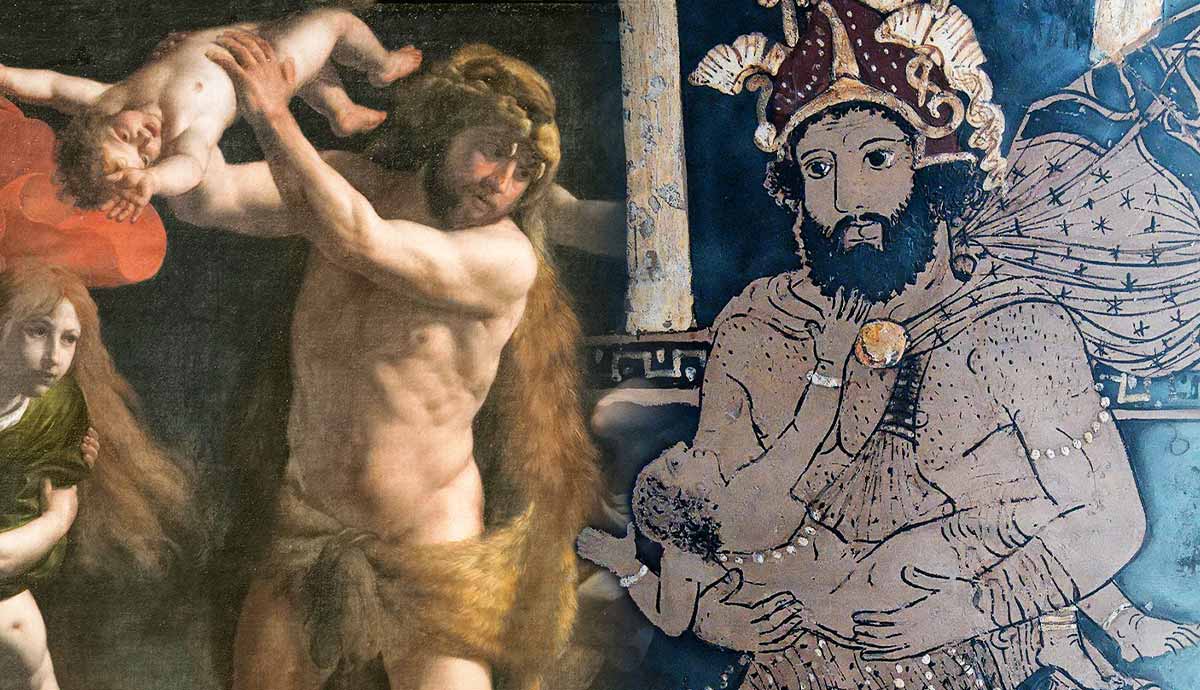

Children of Megara

After his adventure in Thespiae, Heracles became a celebrated hero in Thebes after defending its citizens against the army of King Erginus of Orchomenus. As a reward, Theban King Creon offered Heracles his eldest daughter, Megara’s hand in marriage. Heracles and Megara settled into a happy marriage and had multiple children. Although sources vary on the exact number of children, the four most commonly named are Therimachus, Creontiades, Ophitus, and Deicoon.

Unfortunately, these children were not destined for greatness: fate had determined that they, along with their mother, would tragically die at the hands of their father while Heracles was under Hera’s curse of madness. This event ultimately led Heracles to embark on his famous twelve labors to atone for their deaths. In nearly all versions of the story, the children of Megara are destined to die, but there are differences in how their tragic tale is told. In some versions, Megara does not die but instead divorces Heracles after their children’s deaths and remarries Heracles’s friend and nephew, Iolaus. In Euripides’s play Heracles and the Roman adaptation Hercules Furens by Seneca the Younger, the children are killed by their father after he completes all twelve of his labors.

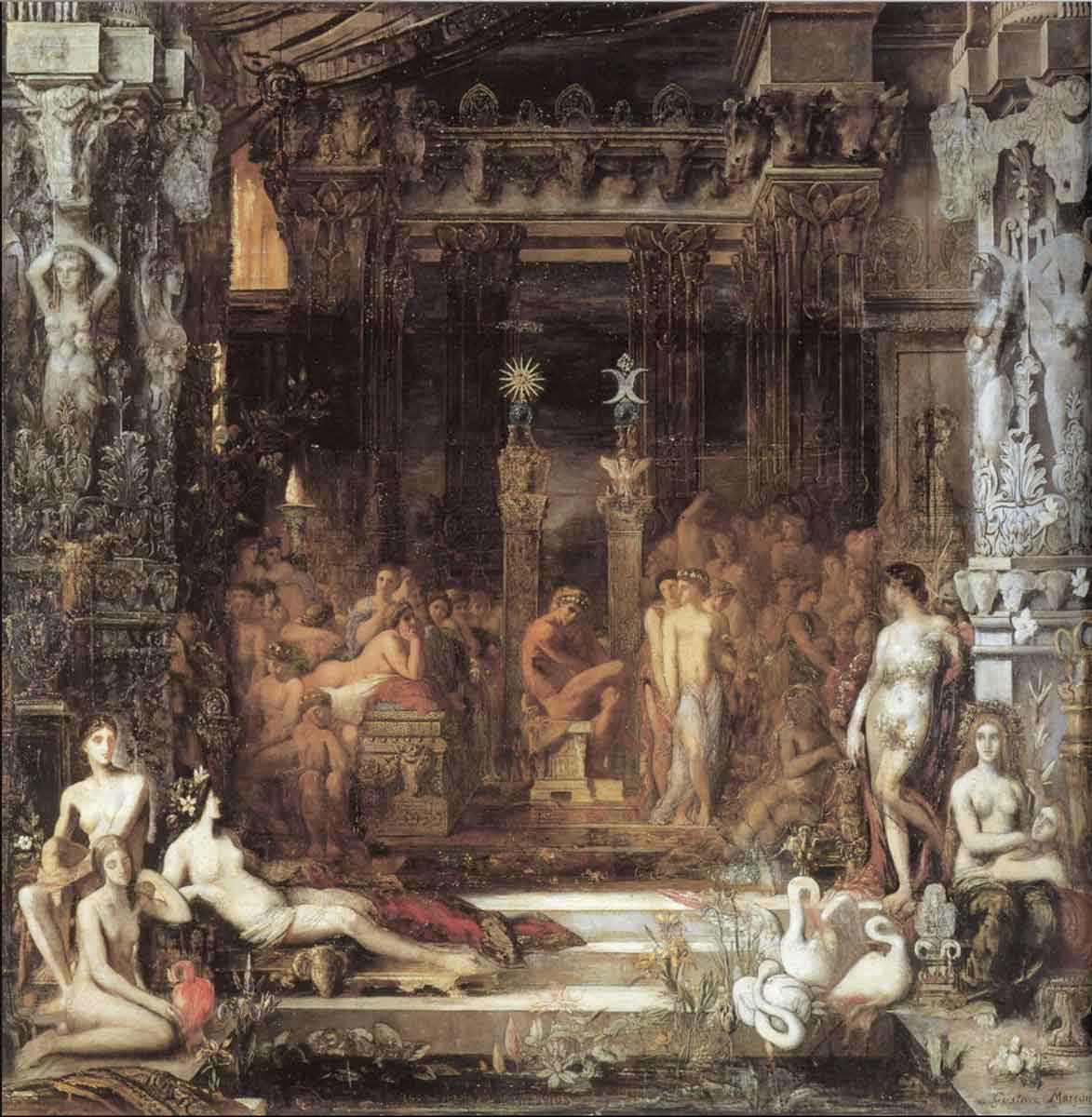

Children of Omphale

After completing his twelve labors and atoning for the murder of his first family, Heracles sought a new wife. However, his search led him back to where he started after he lost his temper and killed a guest, Iphitus, the brother of Iole, the woman he had hoped to marry. Killing a guest was a severe crime, and Heracles went to the Delphic oracle, who instructed him to atone by serving Queen Omphale of Lydia as an enslaved person for three years. Heracles performed various dangerous and degrading tasks for Omphale. She also enjoyed wearing his lion skin cloak and delighted in forcing Heracles to dress as a woman.

Heracles and Omphale eventually became lovers and married. They had two sons, Agelaus and Tyrsenus. Agelaus became the ruler of Lydia and was the ancestor of King Croesus, who ruled in the 6th century BCE. He was known as one of the wealthiest rulers of his time, consulted the famed Solon of Athens, and lost his kingdom to Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid or Persian Empire. Tyrsenus is said to have invented the trumpet, then left Lydia, drove the Pelasgians out of Italy, and settled in the region of the Tyrrhenians in Etruscan Italy.

It is believed that Omphale was not Heracles’s only lover during his enslavement. Before marrying Omphale, Heracles had a son called Cleodaeus or Alcaeus with a woman named Iardanus, who was also enslaved and working for Omphale. According to Herodotus, the descendants of this child founded a long-lasting Heracleidae Dynasty that ruled the city of Sardis in Lydia.

Children of Deianira

During his twelfth labor in the underworld, Heracles encountered the spirit of his friend, Meleager of Calydon, who had perished during the Calydonian boar hunt. Heracles asked if there was anything he could do for his friend in the land of the living, and Meleager asked him to marry his sister, Deianira. Despite taking several years, Heracles eventually fulfilled Meleager’s last wish and married Deianira.

The couple had a loving relationship but their marriage, combined with natural insecurity, pride, and a centaur’s desire for revenge, would lead to the deaths of both Deianira and Heracles. Before their deaths, Deianira and Heracles had five children: four sons, Hyllus, Ctesippus, Glenus, and Onites, and a daughter, Macaria. The eldest son, Hyllus, became the leader of the Heracleidae, and very little is detailed about his three brothers. At the same time, his sister Macaria plays a significant role in Euripides’s play Heracleidae.

King Eurystheus of Mycenae, who organized Heracles’s twelve labors, hated Heracles, and this hatred also extended to his children. Before they were born, Zeus had decreed that Heracles would rule over Mycenae but due to Hera’s trickery, Eurystheus became the ruler instead. Eurystheus’s hostility arose from his fear that Heracles or his children would take Mycenae from him. After Heracles’s death, Eurystheus dispatched armies to find Heracles and Deianira’s children to kill or arrest them. The might of Eurystheus’s army resulted in the children being denied protection in every city they sought refuge in until they finally found sanctuary in Athens under the rule of King Demophon, son of Theseus.

When Eurystheus threatened to invade Athens, Demophon refused and prepared for battle with Heracles’s sons. Before the fight began, an oracle told Demophon they would win if they sacrificed a noble virgin girl for Persephone. Demophon refused to force any noble Athenian women to undergo the sacrifice, but Heracles and Deianira’s daughter, Macaria, volunteered. In Euripides’s play Heracleidae, Macaria, also known as the Maiden, explains her decision and the challenges of finding happiness in her situation. Thanks to Macaria’s sacrifice and the bravery of Demophon and Heracles’s sons, Eurystheus and his army were defeated.

The Return of the Heracleidae

After defeating Eurystheus, Hyllus and his brothers invaded the Peloponnese to reclaim their father’s birthright. They conquered most cities but had to retreat due to a plague. Hyllus sought refuge in Thessaly with Aegimius, King of the Dorians. Aegimius rewarded him with a portion of his kingdom because Heracles had helped Aegimius defeat the Lapiths years earlier. Aegimius adopted Hyllus and appointed him his successor, beginning the Heracleidae’s rule over the Dorians.

Hyllus sought advice from the Oracle of Delphi, who instructed him to wait for “the third fruit” and invade the Peloponnese through a narrow sea passage. Hyllus interpreted this as waiting for three years and then invading the Peloponnese through the isthmus of Corinth. Three years later, Hyllus and his allies invaded and fought against Atreus, the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus, who had taken control of Mycenae in Eurystheus’s absence. Hyllus faced King Echemus of Tegea in single combat and died, leading to the retreat of the Heracleidae armies.

Over the following decades, Hyllus’s son Cleodaeus and grandson Aristomachus attempted but failed to invade the peninsula. Hyllus’s great-grandsons, Temenus, Cresphontes, and Aristodemus, returned to the Delphic oracle to learn why their forbears had failed. The Oracle revealed a misunderstanding of the prophecy: the “third fruit” referred to three generations, not three years, and the “narrow sea passage” was the straits of Rhium, not the isthmus of Corinth.

The brothers started building a navy for the fifth Heracleidae invasion of the Peloponnese. Still, their fleet was destroyed, and Aristodemus was killed because a Heracleidae named Hippote had murdered a soothsayer named Carnus.

Temenus returned to the oracle, who instructed him to offer a sacrifice, exile Hippotes for ten years, and find a three-eyed man to lead the invasion. Temenus recruited a one-eyed man named Oxylus, riding a two-eyed horse, whom he believed to be the prophesied three-eyed man. The Heracleidae rebuilt their fleet, launched an invasion, and conquered Mycenae after defeating Tisamenus, son of Orestes. The Heracleidae then divided the peninsula, with Temenus taking Argos, Cresphontes taking Messene, and the twin sons of Aristodemus taking Lacedaemon, becoming the first dual kings of Sparta. Oxylus was given to Elis for his contribution.

The Dorian conquest of the Peloponnese was known as the return of the Heracleidae. In ancient Greece, noble families often claimed a hero as an ancestor, and Dorian nobles in the Peloponnese claimed Heracles and his descendants as their own. The absence of any mention of the return of the Heracleidae by Hesiod or Homer suggests that the invasion may have some basis in actual history. Moreover, it is likely that the Dorians justified their invasion based on the stories connecting them to Heracles and the Heracleidae. However, the extent of this is uncertain.

Divine Children

After Heracles died, he ascended to Olympus and became a god. On Olympus, Heracles married Hera’s daughter Hebe, her cupbearer, and goddess of youth. Together, Heracles and Hebe had two sons, Alexiares and Anicetus. The brothers became guardian deities responsible for protecting the fortifications of towns and citadels. They also became the gatekeepers of Olympus, a position often attributed to their father, Heracles.

Another divine child of Heracles was Eucleia, the personification of glory and good repute. She is the daughter of Heracles and Myrto, Patroclus’s sister. Eucleia is one of the three younger Charites or Graces, a group of goddesses who preside over charm, joy, beauty, and many other pleasures of life.

Tlepolemus

Tlepolemus, the son of Heracles and Astyoche (daughter of King Phylas of Ephyra) was a prominent figure among the Heracleidae. After being exiled for killing Licymnius, Heracles’s uncle, Tlepolemus established a kingdom on the island of Rhodes. According to Homer, Tlepolemus led a fleet in the Trojan War and was ultimately killed by the Trojan hero Sarpedon.

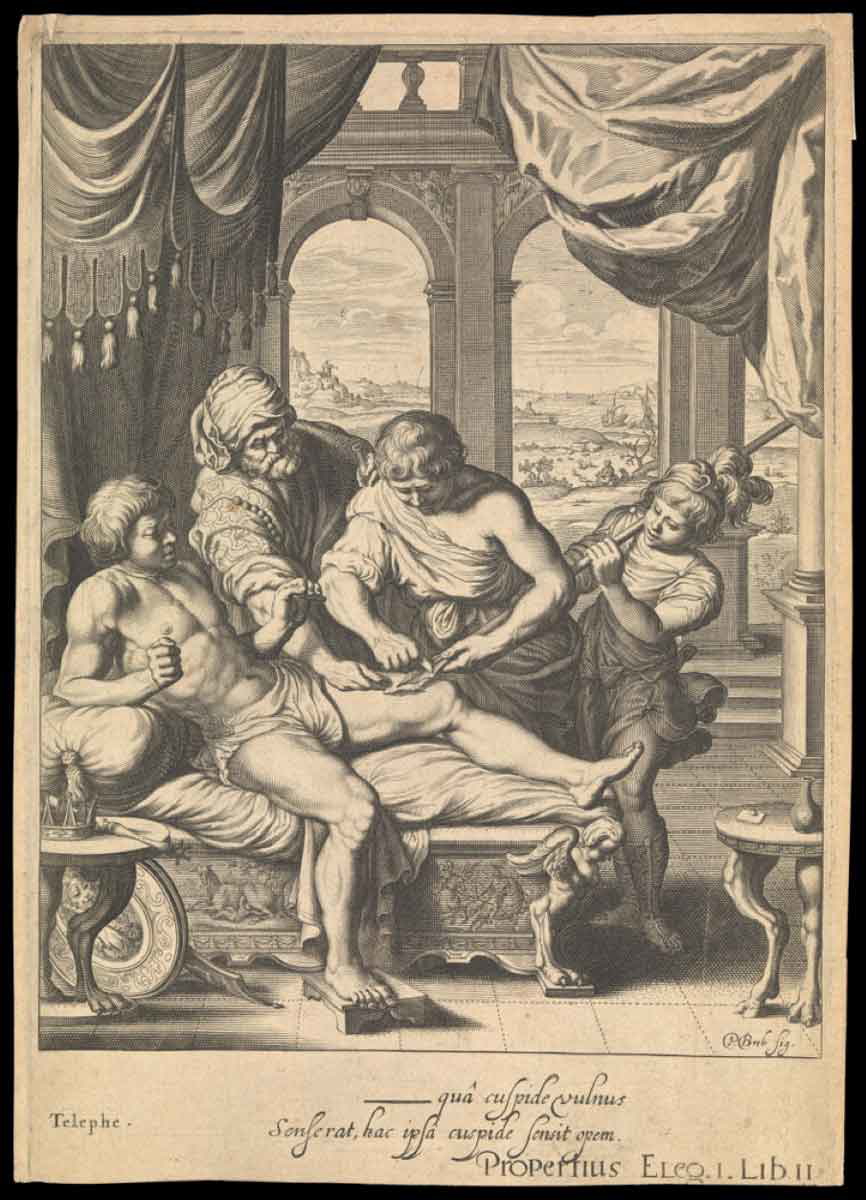

Telephus

The hero Telephus, the son of Heracles and Auge of Tegea, is described as the most similar to his father in strength and ability. Multiple, often contradictory accounts of Telephus’s life exist. Still, they all share a typical narrative journey ending with him becoming king of Mysia, fighting Achilles, and guiding the Greeks to Troy.

Telephus’s mother, Auge, was a virgin priestess of Athena when Heracles seduced her. In some versions, her father, King Aleus, had forced her to become a priestess because a prophecy claimed his grandchild would murder him. Regardless, the scandal of a chaste priestess falling pregnant was too much, and Auge was exiled from Tegea. In every version, she ends up in Mysia in northwestern Anatolia, where the childless King Teuthras marries her and adopts Telephus, or else adopts Auge as his daughter. In one version, Aleus hires a man named Nauplius to drown Auge on her journey to Mysia, but she gives birth to Telephus on the side of Mount Parthenion. Afterward, Nauplius decided to sell her to Teuthras.

In one popular version of the story, Auge leaves the newborn Telephus on the side of Mount Parthenion. Telephus is saved by a deer that nurses him until a herdsman finds him and takes him to King Corythus, who raises him as his son. When Telephus grows up, he consults an oracle to find his mother. The oracle directs him to Mysia, where he is reunited with Auge. Teuthras then adopted him and appointed him the heir of Mysia.

However, Auge and Telephus are unaware of their relationship in many accounts. When Telephus arrives, Teuthras asks him to defeat his enemy, Idas. In return, Teuthras promises to give Telephus his kingdom and his adoptive daughter Auge’s hand in marriage. With the help of his best friend Parthenopeus, son of Atalanta, Telephus defeats Idas and receives Teuthras’s reward. Auge, who still loves Heracles, refuses to marry Telephus and tries to kill him in their wedding chambers. The gods intervene by sending a snake to stop Auge. Telephus then attempts to kill Auge, but she calls for Heracles to save her, leading them to realize they are mother and son.

In time, Telephus took over as King of Mysia, and shortly afterward, the Trojan War began. Due to their proximity, the Greek army mistook Mysia for Troy and attacked the city. However, Telephus, blessed with his father’s strength and talent, easily defended Mysia and forced the Greeks to retreat. As the Greeks fled, Dionysus caused Telephus to trip on a vine as punishment for not worshiping him properly. When Telephus fell, Achilles wounded him with a spear in his thigh. While the Greeks struggled to find Troy, Telephus’s wound refused to heal and began to fester. He consulted the oracle of Apollo, who told him that only his attacker could heal him.

Telephus traveled to Greece in search of Achilles. In some versions of the story, he meets Clytemnestra, who suggests he kidnap King Agamemnon‘s son, Orestes, to force the Greeks to help him. However, the abduction proved unnecessary as the Greeks were happy to help Telephus once they learned he was also a native Greek. They agreed to let Achilles heal Telephus if he guided the Greek forces to Troy. Telephus agreed, and Achilles healed the injury by scraping rust from the spear he had used into the festering wound. The Greeks invited Telephus to join them, but he declined because his wife, Astyoche or Laodicea, was the sister or daughter of Priam, the King of Troy. However, Telephus’s son, Eurypylus, decided to join the Trojans and died fighting during the war.

The Eponymous Children of Heracles

Many of Heracles’s children were believed to be the eponymous founders of cities, kingdoms, and societies around the ancient world. For instance, the ancient city of Amathus in Cyprus was thought to have been founded by Heracles’s son Amathes. Mantua in Italy was named after Hreacles’s daughter, Manto. The ancient town of Olynthus was named after the son of Heracles and Bolbe, a water nymph who lived in Lake Volvi.

In Greek and Berber mythology, Sufax was the son of Heracles and the goddess and queen of Libya Tinjis. Sufax founded the city of Tangier, which he named after his mother. Heracles met Tinjis after defeating her husband, Antaeus, in a wrestling match during his tenth labor. During the same labor, while Heracles herded Geryon’s cattle from Iberia to Greece, he passed through the land of the Celts and met a local princess named Celtine. The princess fell in love with Heracles, stole some of his cattle, and refused to return them until they slept together and had a son, Celtus, the ancestral founder of the Celtic people.

The children of Heracles traveled far and wide; for instance, Heracles’s favored daughter, Pandai, was granted rulership of a kingdom in India by her father. According to Pliny the Elder, Pandai became the founding member of the Pandyan Dynasty, which ruled in southern India for centuries.

One fascinating story involves Heracles encountering a half-woman, half-snake creature believed to be the mother of monsters, Echidna, while searching for his horse. Echidna had Heracles’s horse and offered to return it to him if they slept together. Heracles agreed and was given not only his horse but three sons. Echidna asked Heracles what he wanted to do with their three new sons, and he gave her a bow and a belt with a golden buckle. Heracles then told her that the first son, who could bend the bow and put it on the belt, would become ruler of the lands, and the other two would be exiled.

Heracles and Echidna’s three sons were Agathyrsus, Gelonus, and Scythes. In time, Scythes, son of Heracles and Echidna, became the founding ruler of the legendary Scythians by bending the bow and putting on the belt while his brothers were exiled.