From 1096 to about 1300 CE, during the Middle Ages in Europe, European monarchs and other royals sent armies to the Holy Land in the Middle East to attempt to secure the city of Jerusalem and surrounding territory for Christendom. These “holy wars,” fought between Christians and Muslims, had strong sociopolitical impacts on Europe, which was dominated by the Roman Catholic Church. Monarchs participated in the Crusades to win favor with the Pope, show their military might, and bestow rewards and punishments on political allies and rivals, respectively. How did two centuries of religious war in the Middle East affect the kingdoms of Europe?

The Middle Ages in Europe

The Roman Empire collapsed shortly after 450 CE, approximately a century after dividing itself into a Western and Eastern half, plunging Western and Central Europe into a period known as the Dark Ages, or the early Middle Ages. There were several reasons for the Empire’s decline and collapse, ranging from political instability to foreign invasions to the rise of Christianity, which caused internal cultural and political turmoil. The collapse of the Roman Empire resulted in the rise of individual feudal kingdoms, where peasants labored for the benefit of a lord in exchange for protection.

During the Middle Ages, kingdoms expanded in size and organization, with hierarchical ranks of lords and nobles. Loyal nobles would receive lands, including attached peasants or serfs (peasants who were indentured servants), from the king in exchange for assisting the king, especially in military endeavors, whenever called upon. By around 1000 CE, advancements in agriculture and a lack of large-scale warfare had allowed Europe’s population to grow considerably. A new socioeconomic class, merchants, began to emerge in growing towns to facilitate trade generated by excess production in individual feudal manors and kingdoms.

The Power of the Roman Catholic Church in Medieval Times

The original Christian denomination was the Roman Catholic Church, which dominated Europe at the end of the Roman Empire. By 1000 CE, the Church influenced virtually all aspects of Medieval life. Monarchs allied themselves with the Church and used it as a tool of social control, with kings and queens declaring that their rule had been blessed by God… and defying it would result in eternal consequences. The Church amassed considerable wealth by encouraging tithes of 10 percent of economic production, first from aristocrats and then from commoners.

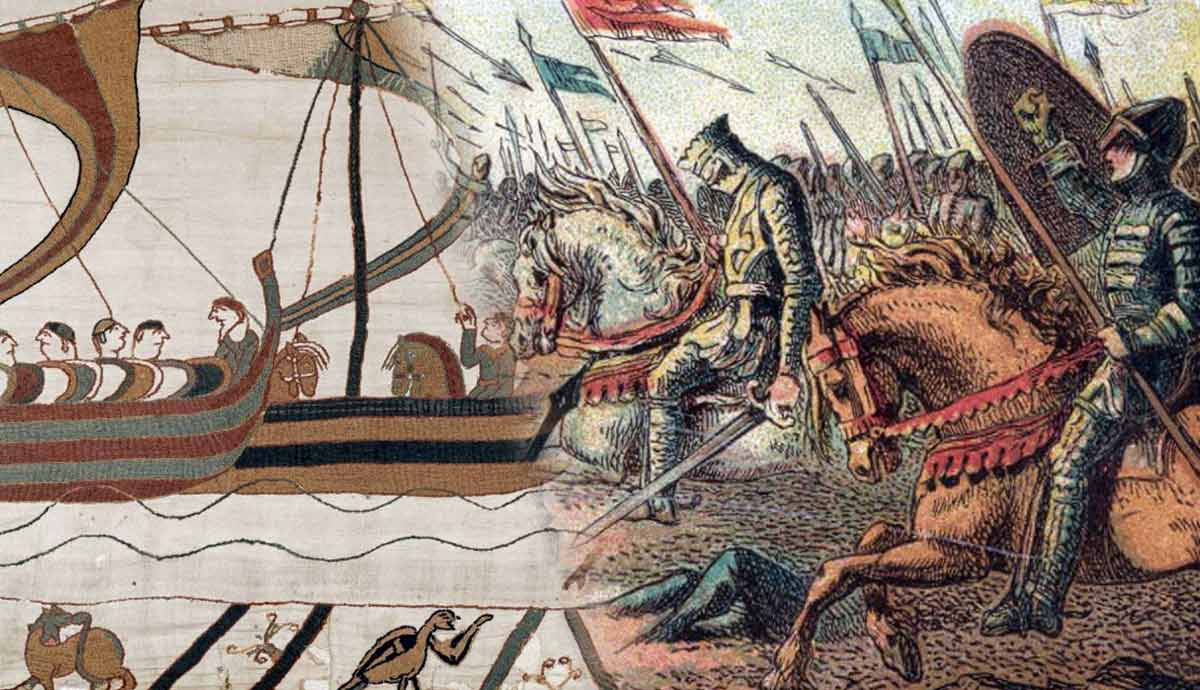

The Church, especially through its centralized leader, the Pope, could influence kingdoms directly by approving wars and invasions. The Norman invasion of England in 1066 was approved by the Pope upon William the Conqueror’s promise to “fix” the Anglo-Saxon Church in England, which had deviated somewhat from the customs of Rome. Additionally, the Pope could either bless kingdoms and their rulers, providing them tremendous legitimacy, or threaten to excommunicate kings who disobeyed the Church. Often, the Pope and his fellow clergy (religious professionals) mediated disputes among European nobles.

The First Crusade (1096-1099)

On November 26, 1095, Pope Urban II gave a famous sermon that prompted a crusade. He encouraged Christians to “fight against the infidel” and unify fellow Christians in the mission to reclaim the Holy Land, as well as absolve one’s past sins by becoming “soldiers of Christ.” Quickly, European monarchs pledged forces to join what became the First Crusade, which embarked in August 1096. Unfortunately, many Christian soldiers engaged in mass violence against all non-Christians they encountered on the way to Jerusalem, including Jews in Europe.

Although the Pope had anticipated a small force of knights, a social movement of up to 100,000 Europeans, mostly poor and relatively untrained, mobbed toward the Middle East. By June 1098, the crusaders had made it as far east as present-day Syria. By July 1099, they had captured Jerusalem after a five-week siege. Many crusaders quickly returned to Europe after securing the Holy Land, but some remained to establish new kingdoms along the Mediterranean coast. Christian cathedrals were built in the Middle East, establishing new cultural centers and traditions.

The Second Crusade (1147-1148)

Christian control of the Holy Land was not to last. In 1144, the easternmost Latin (former Roman) state of Edessa was captured by a Turkish Muslim leader, Prince Imad al-Din Zengi. The fall of Edessa on Christmas Eve, part of a Crusader County from the First Crusade, prompted the Second Crusade. Poor treatment of local Muslims made it difficult for Christian lords to hold their territories, and help from Europe was desperately sought. Pope Eugenius III requested aid from King Louis VII of France in December 1145, and a Pope-allied clergyman sought the same from Emperor Conrad III of the German states.

This crusade had multiple objectives: retake Edessa in the Middle East, push back the Muslims in Spain and Portugal (the Iberian Peninsula), and defeat pagan (non-Christian) forces along the Baltic Sea in eastern Europe. The mission to retake Iberia from the Muslims became known as the Reconquista, and commenced in 1147. In October of that year, English Christians captured Lisbon, and some continued on to the Middle East. There, the Germans under Otto of Freising, Conrad’s half-brother, were defeated by the Turks, and the survivors retreated home. The French fared somewhat better, with Louis VII arriving in Jerusalem in the spring of 1148, to be joined by some Germans under Conrad III. In July, the crusaders attacked Damascus, Syria, but retreated after a day’s combat.

The Third Crusade (1189-1193)

The failure of the Second Crusade was a humiliation for both Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, and both lost power and prestige as a result. In the Middle East, the Crusader Counties, also known as Crusader States, remained until 1187 due to political fragmentation among Muslim leaders. By 1187, however, Salah al-Din ibn Ayyub, known to Westerners as “Saladin,” had united the areas comprising modern-day Egypt, Iraq, and Syria as Sultan of Egypt. Saladin captured Jerusalem on July 4, 1187, prompting Pope Gregory III to issue a papal bull (formal announcement) to prompt a third crusade to retake the Holy City. The rulers of England, France, and the Holy Roman Empire (modern-day Germany) heeded the call to arms.

The Third Crusade, which has been memorialized in popular films, saw King Richard I, also known as the Lionheart, of England battle Saladin over a two-year period. King Philip II of France returned home in 1191 after initial Christian victories. The crusaders were able to retake some Crusader States along the Mediterranean coast, but failed to capture Jerusalem. In 1192, Richard I established a truce with Saladin to allow Christian pilgrims access to the city. The Treaty of Jaffa (1192) granted Christians freedom of passage and the right to exercise commerce. While returning to England the following year, Richard I was captured in Austria after being betrayed by Philip II, sparking years of sporadic fighting between them.

The Fourth Crusade (1201-1204)

Saladin’s continued control over Jerusalem angered many Christians, including Pope Innocent III. This latest appeal to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims was met with mostly a French and Italian response, and far fewer soldiers arrived to sail for the Middle East than was expected. Immediately, the French became embroiled in Italian politics and were manipulated by the leaders of Venice into attacking the Hungarian city of Zara in November 1202. Zara was a Papal State, governed by the Pope, and its being forced back under the control of the Venetians led to the Pope excommunicating all participating crusaders.

Now, instead of liberating the Holy Land, the excommunicated crusaders headed to Constantinople, where an exiled Byzantine promised them riches if they placed him on the throne of the Byzantine Empire. The crusaders succeeded, but resorted to pillaging the city when their re-throned exile, Isaac II Angelos, was assassinated. Instead of reaching the Holy Land, the crusaders established new states in the former Byzantine Empire, mostly in Greece and western Turkey. This empire fell in 1261, when the Byzantines recaptured Constantinople. Ultimately, the Fourth Crusade was a total failure due to its never having liberated any land from the Muslims, and almost all fighting was done among Christians themselves.

Later Crusades (1208-1300)

Crusades continued after the total failure of the Fourth Crusade, but they were smaller and less formally organized. The Fifth Crusade, launched in 1217 by Germans and Italians, was on the verge of capturing an Egyptian coastal city, Damietta, when sultan al-Kamil offered to return Jerusalem to Christian control if the crusaders departed. The Pope’s emissary, Pelagius, refused to sign a treaty, and Damietta was captured in November 1219. Unfortunately for the crusaders, Pelagius’ next mission, to capture Cairo, failed disastrously, and the crusaders were forced to surrender Damietta and return home.

The Sixth Crusade was launched by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, who had been absent from the previous crusade and was thus disdained by the Pope. He married Isabella II in 1225, the daughter of the supposed King of Jerusalem, and thus had a political claim to the Holy City. Due to repeated delays in launching his crusade, Frederick II was excommunicated in 1227. Through shrewd negotiation and his knowledge of Arabic, Frederick II convinced Sultan al-Kamil to cede Jerusalem to him, allowing al-Kamil to focus on other threats. The Treaty of Jaffa (1229) granted Christians a ten-year guarantee for the Holy Land.

In the late 1240s, the Seventh Crusade saw King Louis IX unsuccessfully attempt to capture Cairo, following the same route as the Fifth Crusade. Louis IX was captured and later released, launching the Eighth Crusade in 1269 before dying shortly after arriving in North Africa, collapsing the mission.

The Crusades’ Effects on the Pope’s Power

Until the final stages of the Crusades, which were less organized, these military missions increased the power of the Pope. They gave the Pope, normally a religious figure, military power that could be wielded against perceived enemies of the Church, both outside of Europe and within. Nobles and commoners sought to win papal favor by volunteering for crusades, often doing so in exchange for blessings and promises of divine reward. Crusades were often advertised to prospective soldiers as penance for past sins. The ability of a pope to grant a plenary indulgence (removal of punishment for sin) to participants of a crusade was a major source of power and influence.

During the Crusades, nobles and their soldiers worked on behalf of Christendom, which meant the Church and, ultimately, the Pope. This drastically increased the political power of the Pope, who functioned as a powerful arbiter in secular activities as well as religious affairs. Papal legates represented the Pope during the Crusades and in the Crusader States that were established, granting the Pope direct political influence over civil affairs. However, this increase in power declined late in the crusade era as the missions became unsuccessful, eroding the belief that crusaders were enjoying divine benevolence.

The Crusades’ Effects on Monarchs’ Powers

Similar to popes, kings also enjoyed an increase in power and authority during the Crusades. As administrators of the Crusades, kings and nobles collected tithes, taxes, and volunteers for the holy missions, thereby strengthening their claim to divine right. When it came to fighting, kings gained power at the expense of lower-level nobles, who were sent to the Holy Land and could either die or be made to remain in the new Crusader States. As a result, nobles’ estates in Europe reverted to the king. The absence of nobles during the Crusades allowed kings to exercise more direct control.

Crusades were helpful politically by giving kings an outlet for internal dissent and troublemakers, who could be sent to the Holy Land. Kings who participated themselves, such as Richard I of England, could also gain political power through public admiration for bravery. And sending young men to fight the Muslims in the Middle East benefited European monarchs by providing a common enemy, reducing the incentive to fight each other. Finally, the early Crusades provided some military victories and the establishment of Crusader States, which could be praised and publicized by monarchs to boost public morale.

The Crusades and the City of Jerusalem

The primary goal of the Crusades, controlling the Holy City of Jerusalem, lasted only about 90 years, from 1098 to 1187. Unfortunately, the initial Crusader seizure of Jerusalem, which was surrendered peacefully by its Muslim rulers, resulted in mass violence against Muslims and Jews. Christians built various infrastructure, including many churches and forts. Islamic mosques were often transformed into Catholic churches. Existing Christian churches, such as Eastern Orthodox churches, were modified to incorporate Romanesque features.

Jerusalem, home to many cultures and pilgrims from all three Abrahamic religions, also influenced crusaders who returned home to Europe. Artistic styles from the Byzantine Empire, which many Europeans encountered during the Crusades, were adopted by some European artists. There were countless cross-cultural exchanges due to the wide variety of cultures involved in the Crusades, ranging from Englishmen to Germans to Spanish Moors (Muslims) to Turks. By 1291, the Holy Land surrounding Jerusalem was firmly back in the hands of Muslims, but political reform by the late 1400s protected many Christian churches and synagogues from destruction.

Today: The Legacy of the Crusades

Both Western and Middle Eastern cultures use the Crusades to symbolize the Medieval era. The use of knights on horseback, lengthy journeys through perilous terrain, construction of castles and forts, and religious zeal are often romanticized by enthusiasts of the Middle Ages, with the Crusades perhaps being seen as the epitome of the era. Westerners have periodically sought to recreate elements of the Crusades in more recent eras, such as the colonial era (1798-1930s) in the Middle East, typically seeing Western intervention as both civilizing “backward” locals and protecting Christians. Not surprisingly, Middle Eastern cultures take a more negative view of the Crusades and consider them to epitomize foreign interference and oppression.

In recent years, the term “crusader mentality” has gained popularity, referring to an individual or group that constantly seeks a fight over a perceived moral, ethical, or religious issue. Geopolitically, the Crusades saw a resurgence as a historical reference during the Global War on Terror when the United States and its allies intervened militarily in the Middle East. The location of the targeted terrorist groups, plus many politicians’ desire to portray the Global War on Terror as a battle of good versus evil, had many parallels to the Crusades of the Middle Ages. Controversially, many social and religious conservatives today may ignore the brutality of the Crusades toward civilians and prefer to see it as “Christianizing” and “civilizing” a hostile region.