Diego Velázquez was a celebrated artist of the Spanish Baroque and one of the most important painters in Spanish history. He was a master of complex compositions and rich colors and was known as King Philip IV’s favorite court painter. His paintings evoke deep admiration but also attracted the attention of art vandals. Read on to learn more about the six famous works by Diego Velázquez.

1. Las Meninas, c. 1656: The Greatest Masterpiece of Diego Velázquez

The most famous and celebrated work by Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, had a difficult and eventful history. Translated as The Ladies-in-Waiting, it depicted the young Infanta Margarita, the heiress to the Spanish branch of the Habsburg dynasty. What made the painting particularly fascinating was its complex composition: the young Infanta is at once the center of the composition and its external element. Next to her stands Velázquez himself, painting a portrait—but not that of the girl, but of her parents, Philip IV of Spain and Mariana of Austria, whose reflections we can see in a mirror behind the child.

Apart from its immense political power and wealth, the Habsburg royal dynasty was known for its highly questionable ways of keeping said power in the family. For centuries, they married their close relatives, producing children with increasingly grave genetic diseases and deformations. Weak health and various defects greatly decreased the number of children fit for holding any political posts. Margarita’s younger brother Charles II, the last Habsburg monarch in Spain, had only 10 relatives in his fifth generation instead of 32, expected from a regular person with no history of inbreeding.

He also could not close his mouth properly due to a genetic jaw deformity and probably had an intellectual disability. Before Margarita’s birth, her family expected her to be born with similar defects. Although the infanta had weak health, she looked almost angelic, with no visible deformations that ran in her family. This was seen as a miracle in the dynasty.

Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress, by Diego Velázquez, 1659. Source: Wikipedia

Apart from Las Meninas, Velázquez painted five more portraits of Margarita. Almost all of them were created for her future husband, Leopold I, the Holy Roman Emperor, who was both her uncle and cousin. Their marriage was pre-arranged even before the Infanta reached the age of ten, and the official ceremony took place when the king and queen were 26 and 15, respectively. Six years later, Margarita died during her seventh pregnancy.

The famous painting survived several fires and evacuations. The large crowds in the Prado museums also contributed to its destruction; thus, Las Meninas never leaves the museum walls for exhibitions abroad.

2. Philip IV in Brown and Silver, 1631-32

Diego Velázquez had a remarkable career at the Spanish Royal Court. Already in his early 20s, he was an established and well-known painter in his native Seville. At the age of just 24, he was appointed the court painter to Philip IV of Spain, the father of Infanta Margarita, after the previous court painter suddenly died. Velázquez was backed up by Gaspar de Guzmán, Count-Duke of Olivares, the minister who manipulated the King and operated the court.

Philip IV was notoriously easy to influence, perhaps due to his hereditary health issues. Olivares was the de facto ruler of Spain, managing the King’s affairs and running military campaigns and financial reforms. To maintain his position, Olivares separated Philip IV from any possible sources of influence. One of the threats to the minister’s power was the monarch’s wife, Elizabeth of France. Elizabeth was much more intelligent than her husband and understood Olivares’ manipulation. To isolate her from her husband, the minister provided the King with dozens of ministers to keep him busy. After Olivares was removed from his post, Philip IV recognized the ambition and talent of his wife, but it was too late as she soon died as the result of a miscarriage.

Elizabeth rarely posed for Velázquez. Knowing his affiliation with Olivares, she avoided contact with the artist. Philip IV, on the contrary, appeared in the artist’s paintings quite frequently, remaining his patron for almost four decades.

3. The Triumph of Bacchus, 1628-29

By the time Velázquez painted The Triumph of Bacchus, he already worked as a court painter for several years. According to some art historians, at that time, the artist started to receive criticism for his supposed lack of versatility, as if he was only qualified for painting portraits. In The Triumph of Bacchus, he blended together the iconography of a mythological scene with that of genre painting. The source material for the work probably came from the royal art collection of Philip IV. The scene itself represented the god Bacchus offering wine to Spanish laymen, dressed according to the customs of Velázquez’s time. Here, wine is a blessing that allows them to take a break from their hard work and misery. Velázquez designed the composition specifically to include the viewer in the image; two central figures look at us as if inviting us to join their feast.

4. Christ in the House of Martha and Mary, 1618

This early work of Diego Velázquez has already shown his versatility and skill in building complex compositions and multi-faceted relationships between characters. Despite the work’s title, the Biblical episode takes only a small corner of the work, reflected in the mirror. According to the story told in Luke’s Gospel, Jesus arrived at the home of sisters Martha and Mary. Their subsequent conversation focused on the prevalence of spiritual values over physical comfort.

However, the central part of the scene is occupied by the sisters’ maid making garlic sauce for dinner. Behind her is an old woman, giving advice—most likely, she was Velázquez’s relative, as she has previously appeared in his other work titled Old Woman Frying Eggs. Velázquez combined a religious scene with genre painting with a specific Spanish type called bodegon. This term usually refers to still-lifes of kitchens or shops painted on dark backgrounds and representing the everyday activities of ordinary Spanish, like cooking or drinking. They also often included figures of maids, cooks, and street vendors.

5. Rokeby Venus, 1647-51

Apart from painting court portraits, Velázquez occasionally relied on mythological subjects. One of such works was Rockeby Venus, inspired by similar paintings by Peter Paul Rubens and other masters Velázquez admired. Just like in the case of Las Meninas, the artist used a mirror to add complexity to the composition—although Venus is lying with her back to us, we can still see her face in a mirror held by Cupid. However, she is not looking at the reflection, with her face turned in a different direction. The unrealistic curve of her elongated spine makes her an expressive predecessor to Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque. Although the Spanish Inquisition disapproved of the painting of nude figures in Velázquez’s time, this work was requested by Philip IV, so the artist was not afraid of prosecution.

In the centuries following its creation, Rokeby Venus fell victim to activist vandalism twice. The first and most famous incident occurred in 1914 when suffragette Mary Richardson attacked the painting with a meat cleaver. She had two motives: the first one was her annoyance with male visitors who were almost drooling at the work. The second reason was the arrest of the leader of British suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst. In retaliation for arresting a politically active woman, the activist wanted to harm the epitome of femininity in the public eye. The painting was successfully restored and covered with protective glass. In 2023, the attack happened again when a group of climate activists shattered the glass with hammers, demanding immediate changes in the fossil fuel industry.

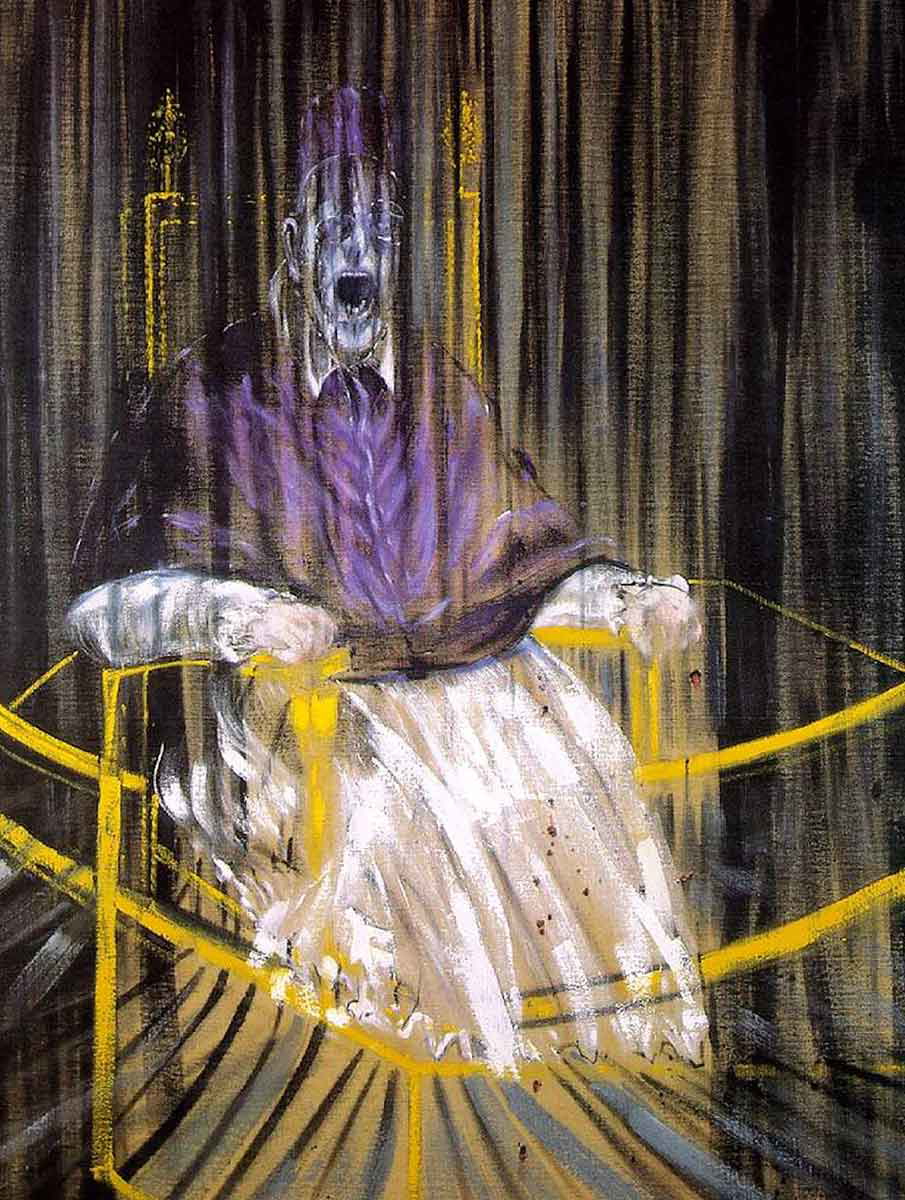

6. Innocent X, c. 1650: The Great Masterpiece of Diego Velázquez

Perhaps the most celebrated artwork by Velázquez that developed a life of its own was his portrait of Pope Innocent X. Some art historians go as far as to consider it the best example of a portrait ever created in the history of art. Pope Innocent X had a rather unflattering reputation and was known for his greed, cruelty, and penchant for intrigues. He was so notorious that the Italian painter Guido Reni gave his facial features to Satan in the scene of his fight with Archangel Michael. Velázquez painted the Pope alert, suspicious, and apparently so realistic that Innocent X refused to exhibit it publicly, displaying it only in front of his family.

The portrait received a new life in the latter half of the 20th century when British artist Francis Bacon encountered it. In the 1950s and 1960s, he painted 45 variations of the portrait, known as The Screaming Pope. The figure’s face was distorted in a horrid scream, unheard, yet still chilling, as if the ugly nature of the sitter suddenly broke loose from behind the respectable facade, tormenting the Pope and causing him unimaginable suffering. Most likely, Bacon blended the figure of Innocent X with another cultural reference he often used: that of a screaming one-eyed nurse from the Soviet silent film Battleship Potemkin.