They say that “history is written by the victor,” which basically means that those in power decide the historical narrative, and those without power are often left in obscurity. In the case of the women of the Celtic nations, their stories are overshadowed both by the history of men, and the history of the English, which is the focus of most histories of the British Isles. With that in mind, this article celebrates the fascinating lives of eight important women from the Celtic nations of the British Isles. There are generally thought to be six Celtic nations: Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, and Brittany.

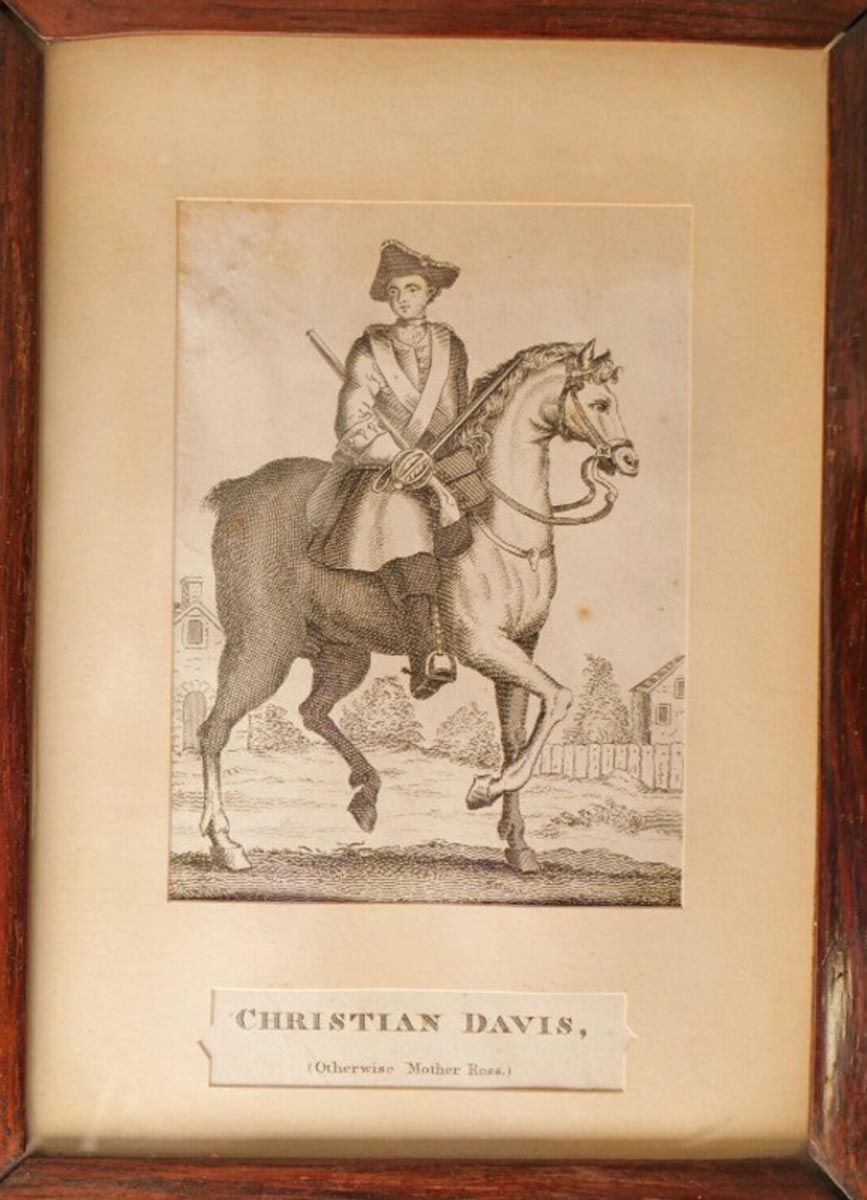

Christian Davies

Christian Davies or Christian Cavanagh was born in Dublin in 1667 and subsequently married a man called Richard Welch, sometimes referred to as Walsh. Although the circumstances are unknown, Richard abandoned his heavily pregnant wife and two young children to join the British Army. Apparently unimpressed, Christian, who went by “Kit,” gave birth and handed all three children over to her mother.

Christian was a woman on a mission. She cut her hair in the style of a man and enlisted in the army with the aim of tracking down her traitorous husband. Christian now went by Christopher, which, luck would have it, was also typically shortened to “Kit.” Her gender went completely unnoticed, and Kit found herself on the frontlines of the Battle of Landen against France.

Kit was wounded in battle and taken as a prisoner, but was later released as part of an exchange of prisoners. Shortly after returning to duty, Kit was involved in a quarrel over a woman, which led to a duel where she shot and killed a sergeant. Consequently, Kit was relieved of duty, but undeterred, she re-enlisted and continued fighting in the Nine Years’ War and the War of the Spanish Succession.

It seemed that Kit really took to army life and was known for looting and raiding in the wake of battle. Yet, her life was not free from trouble as a prostitute accused Kit of fathering her child, and perhaps to maintain her cover, Kit went along with the story and even provided financial support.

At the Battle of Blenheim, Kit was shot in the leg but fought on and guarded the French prisoners after the victory. While still stationed in what is present-day Germany, Kit came upon a soldier flirting with a woman. Kit was outraged because the soldier in question was her husband Richard, but the two seemingly made peace with one another. Furthermore, they maintained that Kit was a man, Richard’s brother.

Kit’s disguise was upheld for another two years until she was struck in the head in battle and was attended to by the army doctor, who swiftly realized she was a woman. Surprisingly, the regiment actually rallied around Kit and ensured she was paid until she recovered. Kit was then transferred to her husband’s regiment as a provisioner, albeit she cut another woman’s nose off for sleeping with Richard.

In 1709, Richard Welch was killed in another battle of the War of the Spanish Succession. Kit formed a relationship with a man named Captain Ross before marrying another soldier, Hugh Jones, but he died the next year. In 1712, Kit returned to Britain, and she, along with her regiment, was shown to Queen Anne. Kit married once more, this time at home in Dublin in 1713.

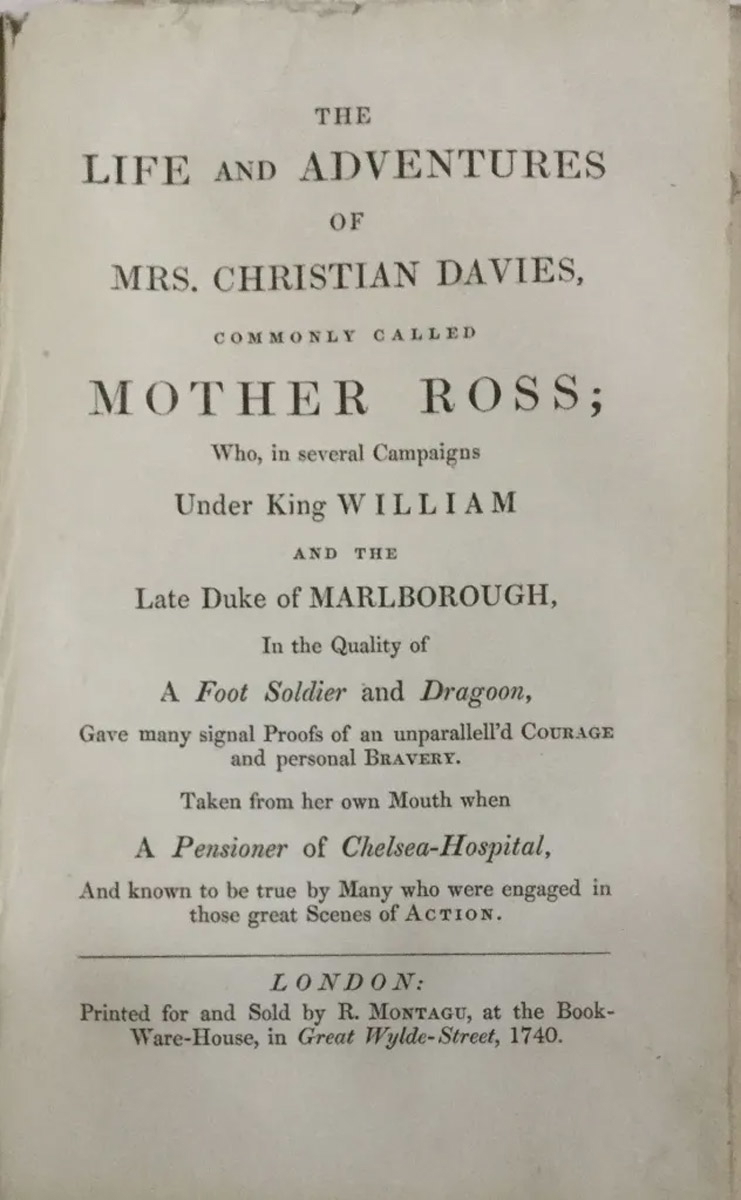

In her later years, Kit resided at the Royal Hospital in Chelsea, London, which provided care for retired veterans. She passed away in 1739, aged 72, and was buried with military honors. A book was anonymously published a handful of years after her death, titled “The Life and Adventures of Christian Davies.” It is now ascribed to Daniel Defoe. Kit undoubtedly displayed courage and determination throughout her life, and she has gone down in history as an unashamedly fiery woman.

Margaret Plunkett

Margaret Plunkett was born in 1727 and was one of 22 children born to fairly wealthy parents in Killough, Westmeath, in Ireland. Only seven of her siblings survived to adulthood, and the family ensured all the children received a good education. All was well for young Margaret, who went by Peg, until the sudden death of her mother and eldest brother due to an outbreak of smallpox.

With Peg’s father too old and devastated by the loss, the family was ruled by his next eldest son, Christopher. Christopher spent many years attempting to stop any family money from going to his siblings. For example, he forbade another one of his sisters from marrying, as it would mean giving her a portion of the estate as dowry. The sister did not care as she loved the man. They ran away to Dublin and married. Young Margaret went with the couple.

In Dublin, Peg became a socialite and received innumerable marriage proposals, all of which Christopher refused. After a brief stint back home that Christopher had forced upon her, Peg escaped to Dublin yet again. A vulnerable young Peg then found herself in a relationship with an older man named Mr Dardis, but the couple separated quickly. Peg’s next relationship was with a wine merchant, and then a Mr Leeson, who historians have presumed was Joseph Leeson, 2nd Earl of Millport.

In both of these relationships, Peg was a mistress, and her liaison with Mr Leeson was cut short when he learned that she was involved in other affairs. Peg was undaunted, as she was not short of suitors, and coupled up with a Mr Lawless. The pair had six children, although only one survived infancy. Nevertheless, Peg’s situation only got worse as her companion suspected her of disloyalty and left without Peg for America.

Seemingly put off long-term romantic relations, Peg and her friend Sally set up a successful brothel on Drogheda Street. However, Peg did not have long to enjoy her prosperity as a prominent gang of thugs entered and destroyed the business. As well as ruining the property, the gang attacked the women. Sadly, the then-pregnant Peg was beaten so hard that she miscarried, and her young daughter was killed.

Peg refused to give in and took the leader of the gang, Robert Crosbie, to court. Crosbie threatened Peg with violence, to which she replied that she had her own pistol. Peg won in court, with Crosbie sent to jail and ordered to pay reparations. With the money, she relocated her business to a nicer area where her new clientele were among Dublin’s high society. As a madam, Peg swiftly began to move among the upper echelons and was known for her wit and charm.

An exaggerated example of a crinoline. Source: Molly Brown House Museum, Denver

Peg was famous for sporting the latest fashions and even wore the first hoop skirt in Dublin, which became a favorite of the elite in the 1800s. Despite her popularity, Peg still faced opposition. Never one to back down, she took the owner of a theater who refused her access to a show to court and won again. She reportedly refused to give way to the royal carriage of the Prince Regent and stated there was room for both. In addition, she noted that the English are subservient and fearful, but the Irish are not.

Upon retirement, Peg’s lavish lifestyle had caught up with her. She was near bankruptcy. In a bid to make money, Peg wrote and published her own memoirs that, by her own accord, were full of scandal and risque tales. The memoirs were an enormous success, although Peg died at 70 before the final installment, Volume 3, was released. The Dublin Evening Post printed her obituary, where it was said she lived in glamorous dignity.

Elspeth Buchan

In 1738, Elspeth Buchan was born to her parents, John Simpson and Margaret Gordon, who owned an inn in Scotland. Despite a relatively pleasant start to life for the time, Elspeth’s mother died early in her life, and her father struggled to support the family. Elspeth was sent to live with various family members, where she had to work hard. Elspeth married Robert Buchan in Greenock, but the relationship was plagued with issues. They permanently separated in 1783.

Following her divorce, Elspeth moved to Irvine after feeling inspired by the teachings of Hugh White, the Minister of the Irvine Relief Church. Parishioners noticed the pair were strangely close quickly. The rumors became heightened when White professed that Elspeth was a saint and he was her reincarnated child.

This swiftly prompted White’s removal from the Church, but the pair and their devoted followers left Irvine for a farm near Dumfries. Here, they created a commune and rejected the idea of marriage, instead preaching ideas of “free love,” similar to those of the hippie movement from the 1960s and 1970s.

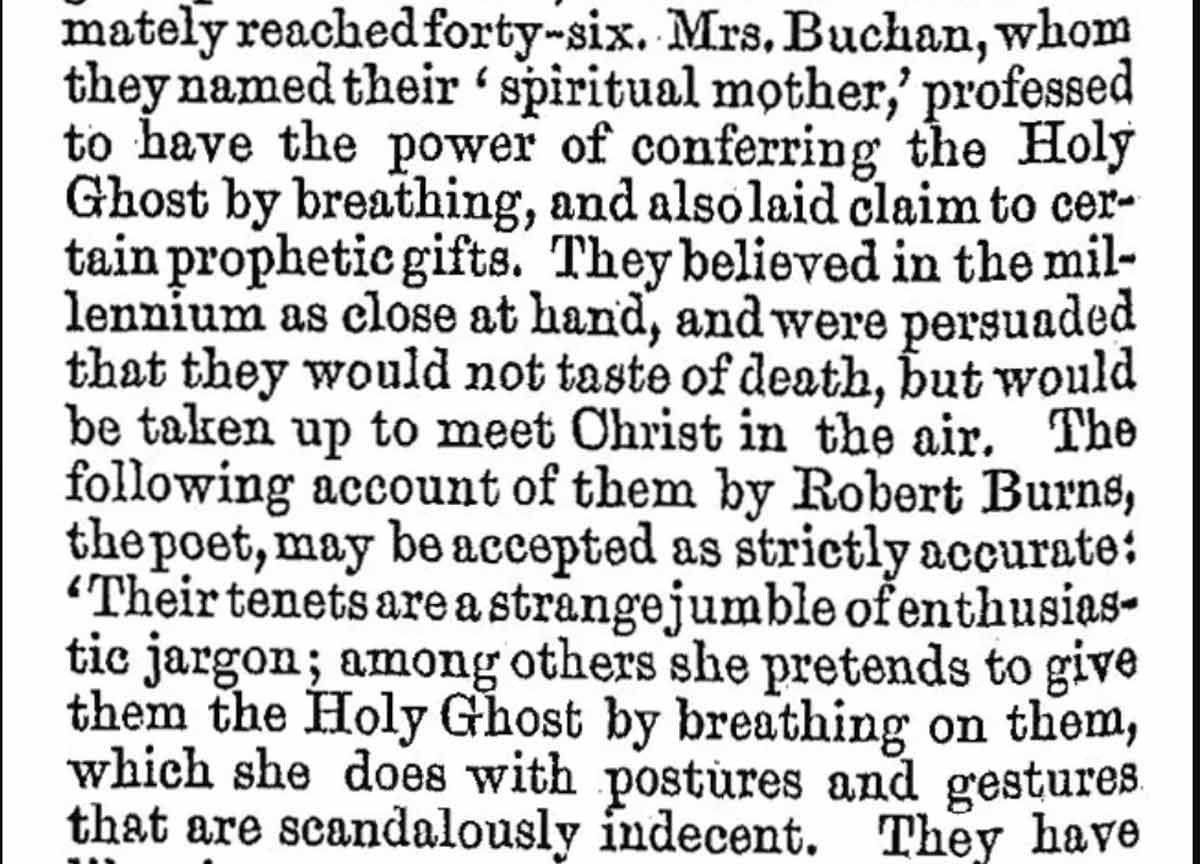

The commune rapidly turned into something comparable to a modern-day cult as Elspeth assumed the title of “Friend Mother in the Lord.” Elspeth asserted she could make people immortal by breathing on them, which would save the commune’s following from an impending apocalyptic event. Robert Burns visited the community in the 1780s and was shocked by what he saw.

Elspeth’s followers were disappointed by her death in 1791, but the commune lived on and patiently awaited her resurrection. Elspeth was a complex woman, something that is rarely shown in the history books. Whilst her character is questionable from what we know of her actions, Elspeth was undoubtedly a smart, charismatic, and powerful woman who was able to command a community of people for almost a decade of her life, and from beyond the grave.

Elizabeth Melville

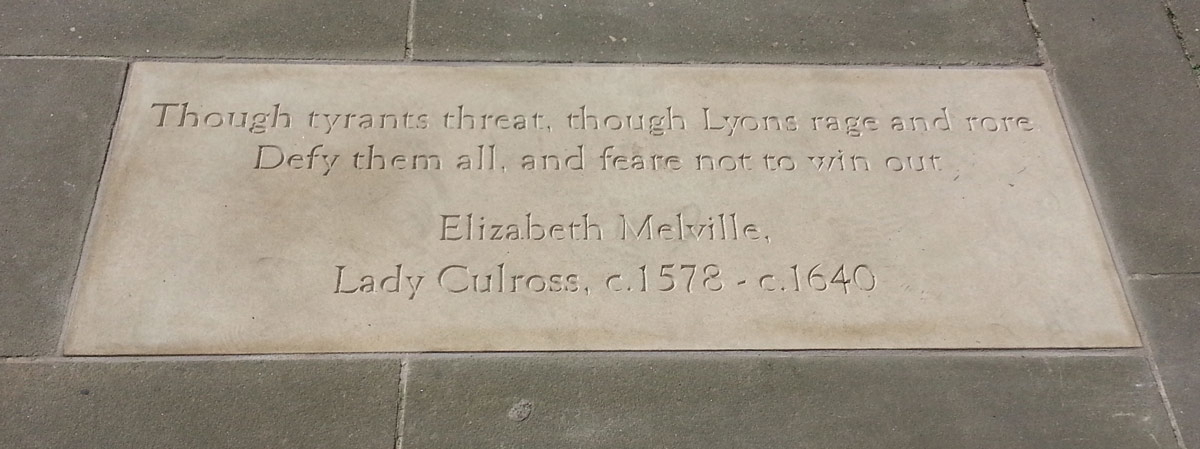

Edinburgh is the historic capital of Scotland, and the city is host to countless statues of men, particularly those who played a large part in the British Empire. In 2004, a stone was unveiled in memory of Elizabeth Melville in the Makar’s Court, “makar” meaning writer in Scots. Elizabeth was born into the Melville family, a wealthy landowning clan in Fife that had been afflicted with scandal for years prior to Elizabeth’s birth. John Melville, Elizabeth’s grandfather, was executed in 1548 for being a Protestant sympathizer.

The Melville family supported Mary I and had strong relations with the Stuarts. However, the family’s religious allegiances changed again when they gained friendship with John Knox, the infamous Protestant Reformer. Elizabeth’s father, James, made sure his daughter was well-educated, and she likely reached adulthood often hearing of the Protestant faith.

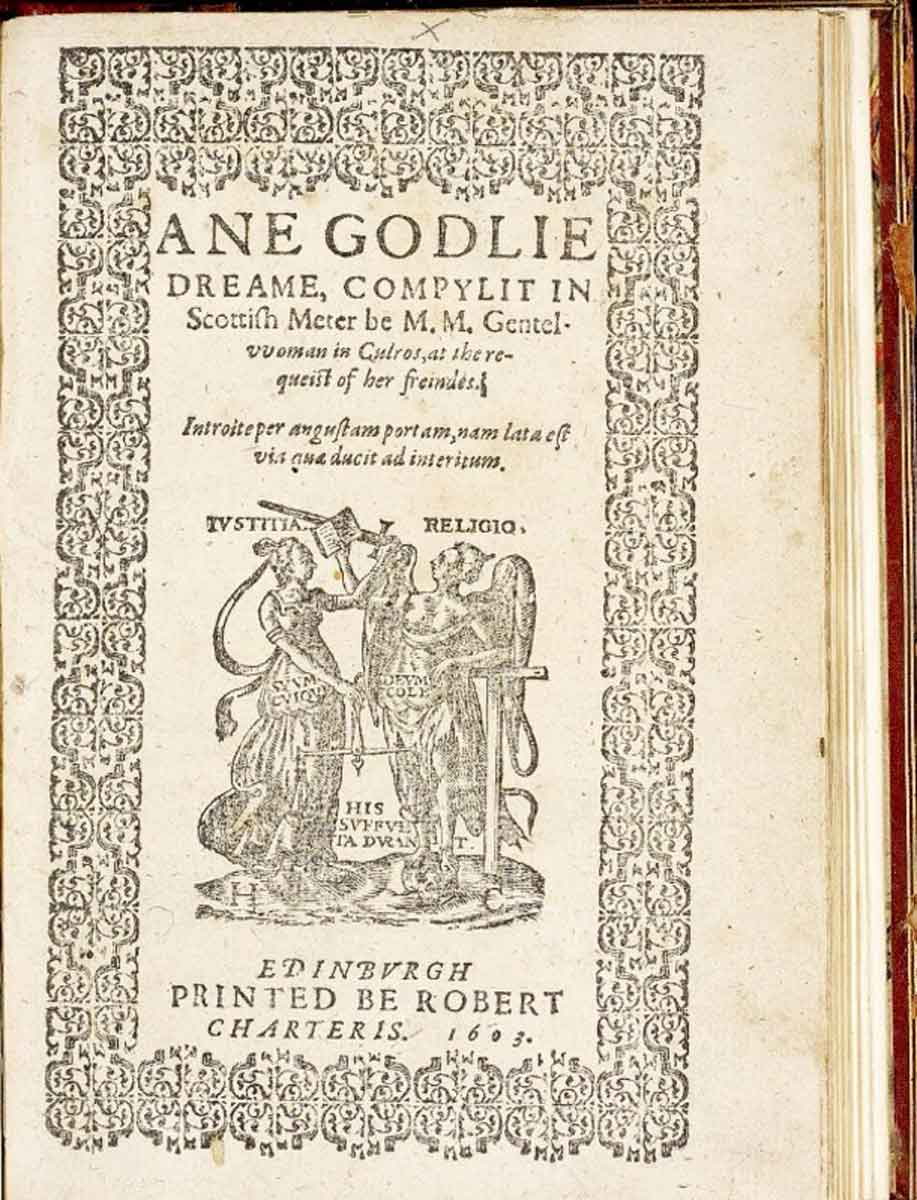

Historians have theorized that James enforced Elizabeth’s education despite this being rare for women at the time due to his encounters with Mary I. Alexander Hume, the poet, described the young Elizabeth as forlorn and gifted in poetry. Elizabeth’s significant work, Ane Godlie Dream, was printed in 1603, which was groundbreakingly audacious for a woman at the time. The work centers upon her internal religious conflict and offers an observation of the Church and state.

Ane Godlie Dream was reprinted multiple times and translated from Scots into English. Elizabeth’s writing was complex. It consisted of 68-line stanzas and rhyming structures. A few of Elizabeth’s other poems were circulated, and works previously unattributed to her have since been credited to her hand, as late as 2002.

Elizabeth’s plaque now resides in the Makar’s Court along with those of six other women: Helen Cruickshank, Dorothy Dunnett, Violet Jacob, Màiri Mhòr nan Òran, Naomi Mitchison, and Nan Shepherd.

Mary Barbour

Like Elizabeth Melville, Mary Barbour also has a statue, although hers is at Govan Cross in Glasgow. Mary’s statue was erected by the Remember Mary Barbour Association, which was created to push for the construction of memorials for women in Scotland as a whole, with emphasis on Mary Barbour’s contribution to political activism.

Mary Barbour was born Mary Rough in 1875, in Kilbarchan, Renfrewshire. Mary married David Barbour in 1896, and their first child, David, was born before the family moved to Dumbarton. Baby David contracted Meningitis and died in 1897, which devastated Mary, who surmised that the squalid conditions the family lived in had something to do with her son’s death. Mary and David had another son, James, in Dumbarton, who was swiftly followed by their third child, William, after the family moved to Govan.

Mary found Govan to be deeply impoverished, but she did not accept that this situation was unchangeable. The still grieving and greatly concerned mother involved herself with various social justice campaigns such as the Scottish Co-operative Women’s Guild and the Socialist Sunday School. The Guild focused on achieving rights for women, such as the vote, education for women, and a national minimum wage, whereas the Sunday School was a national movement for education surrounding the causes and impacts of poverty.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, workers were shipped into Govan to work in the shipyards and factories as part of the war effort, which made the living conditions much worse. While overpopulation soared, the landlords increased the rent, which in turn led to the eviction of poorer workers.

By this time, Mary had joined and became very involved in the Independent Labour Party, which came to be known as the Red Clydeside. The Red Clydeside joined forces with the Women’s Labour League to establish a housing association in protest against the rising rent. In 1915, Mary was among the founding members of a faction of the housing association in South Govan. The female members met in their homes and gathered members of the community when the police attempted to enforce evictions.

The male workers threatened strikes in support of the women and made good on their threat in November of 1915 when they walked out of the shipyards and factories and marched on the Sheriff’s Court to protest upcoming evictions. The protest was a success, and the masses that gathered were dubbed “Mrs. Barbour’s Army.” Furthermore, the actions of the group prompted David Lloyd George to issue the Rent Restrictions Act, which restricted rent to pre-war levels.

Women’s suffrage helped her earn her seat as one of the first women councillors in Glasgow, and in 1924, Mary was appointed Bailie of the City of Glasgow, the first woman to hold the position. Mary’s political career did not end there as she went on to sit on multiple committees where she continually reinforced her dedication to women’s issues and improved living standards for the poorest.

Gwenllian Ferch Gruffydd

On the island of Anglesey in Wales, around the year 1090, Gwenllian Ferch Gruffydd was born into the ruling family of Gwynedd. Gwenllian’s father, Gruffydd ap Cynan, made his name as a warrior and even spent time imprisoned after the Normans invaded Wales; he fought off many challengers for his position as king. Her mother, Angharad Ferch Owain, was from another aristocratic family and was known for her beauty.

Gwenllian was the youngest of eight children and was said to have been as pleasing to the eye as her mother. However, her father, perhaps inspired by his own experiences in battle, ensured his daughter was trained in the use of weaponry.

In the year 1113, another Welsh ruler ventured to the court of Gruffydd ap Cynan, his name was Gruffydd ap Rhys. The younger king had come to ask for help as his land had been taken by the Normans and Henry I of England. By all accounts, Gwenllian’s father did not plan to help Gruffydd ap Rhys and perhaps intended to harm him. So the younger Gruffydd fled with Gwenllian to his family residence further south.

The couple were married, and Gruffydd ap Rhys was given part of his kingdom back from Henry I following a tenuous truce. The family was habitually ousted from their home and moved back and forth from Ireland, but regularly fought skirmishes against the Normans and shared out any spoils of war amongst the Welsh people.

Turmoil in the English court presented an opportunity for the kingdoms of Wales. King Stephen deposed his cousin, the Empress Matilda, which resulted in a series of rebellions across Wales. Gruffydd ap Rhys travelled to Gwynedd to ask for military support from Gruffydd ap Cynan, but the Normans found out and decided to move while the King of Deheubarth was absent.

Maurice de Londres, the Lord of Kidwelly, led the charge against Deheubarth. Gwenllian was not willing to surrender and mustered the troops for battle. Although she fought bravely, Gwenllian’s army was outmanned, and she was beheaded in the aftermath of the Welsh defeat along with two of her sons.

Gwenllian’s efforts galvanized multiple kingdoms across Wales and specifically members of her family in Gwynedd. Two of her brothers took up arms and led armies into Norman-controlled territories in Wales and overpowered many settlements, including Aberystwyth. Furthermore, Gwenllian’s son Rhys succeeded his father Gruffydd and became known as Lord Rhys, Prince of Wales. Lord Rhys played an integral part in future revolts against the Norman overlords and became the dominant power in Wales by 1170.

Despite the success of her son, Gwenllian’s individual legacy carried on in many other ways. Most notably in the Welsh battle cry used for centuries after her death, “Dial Achos Gwenllian,” which means revenge for Gwenllian. The field where she died is also named Maes Gwenllian, or Field of Gwenllian. Additionally, she is said to have been the inspiration for a host of fictional female characters such as Maid Marion in Robin Hood, Guinevere in the Legend of King Arthur, and even Eowyn the shield-maiden in The Lord of the Rings.

Eleanor Gwyn

Not much is known about the early life of Eleanor Gwyn, more commonly known as Nell Gwyn. Eleanor was born in Herefordshire, on the border of Wales and England, to a Welsh father and English mother between 1640 and 1650. Her lineage is also largely unknown, but her surname alludes to an ancient Welsh ancestry, the Gwynnes of Llansannor in South Wales.

In her early childhood, her father abandoned the family, and Eleanor moved with her mother, Ellen, and elder sister, Rose, to Covent Garden in London. To support her children, Ellen set up a brothel and became known as “Old Ma Gwyn.” It is again unknown but within the realm of possibility that Eleanor worked as a prostitute in the brothel, although she later stated she was only a barmaid in the establishment.

Charles II ascended to the throne in 1660 after the rule of Oliver Cromwell and reinstated pleasurable activities that had been outlawed by his predecessor. In some cases, Charles II made further societal advances, such as making it legal for women to perform on stage. Eleanor got a job selling concessions at the Theatre on Brydges Street, later the famous Theatre Royal on Drury Lane, upon its opening in 1663. It is still open today.

The owner of the theater set up an acting school with the help of Charles Hart, which Eleanor joined immediately. By 1665, Eleanor had already made a name for herself, and Samuel Pepys described her as attractive and witty in his diary. Eleanor’s wit and good looks made her popular. She regularly performed in comedies centered upon quick-witted couples making humorous petty triumphs against each other. She frequently starred with Charles Hart, with whom she had become romantically involved.

By this time, Eleanor was known as Nell and had many esteemed gentlemen who coveted her looks and sense of humor. One such man was Lord Buckhurst, who paid Nell £100 a year, the equivalent of £20,000 in today’s money, to have her as his mistress. King Charles II noticed Nell at one of her shows, and she became his lover for several years.

In 1670, Nell gave birth to a son whom she named Charles, and she often noted his significance through his royal father. Although she remained unthreatened by Charles II’s many mistresses, she was famous for having many cruel nicknames for them, such as “Squintabella” for Louise de Kerouaille.

Nell performed her final series of productions in 1676, the same year the townhouse she lived in, owned by the king, was officially given to her. Her influence over Charles II was still felt when her illegitimate son was made a Baron and an Earl, and Nell herself was given a summer residence in central London and a house in Windsor. Nell’s son Charles was later made a Duke and was paid a handsome annual sum of £1000 a year; nearly £200,000 a year today.

Upon the death of Charles II, he granted Nell a pension of £1500 a year, but she had little time to enjoy this fortune as a series of strokes in 1687 left her bedbound. She died on the 14th of November the same year, no older than 45, likely due to syphilis. Humble until the end, Nell left a large portion of her fortune to the poor in her parish.

Charlotte Guest

Charlotte was born into the wealthy and aristocratic Bertie family in 1812 in Lincolnshire, England. Her father was Albermarle Bertie, the 9th Earl of Lindsey, but he died when Charlotte was just six years old. Charlotte’s mother was also named Charlotte and married a clergyman who was also her first cousin after the death of Albermarle.

Young Charlotte allegedly disliked her mother’s new husband but found solace in her studies. She was extremely interested in politics and, through her own research as well as lessons from her brothers’ tutor, Charlotte learned Greek, Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, French, Italian, and Persian. She was also trained in singing and dancing, as was typical for girls of her societal class.

By the time Charlotte was 19, her mother’s health had declined, and she assumed the duties of running a home. Charlotte was noted as having a boundless spirit and took her new responsibilities, along with her continued learning, in her stride. When it came time to find a husband, many men were captivated by her intellect, including Benjamin Disraeli, who went on to become the Prime Minister.

In 1833, Charlotte met the Welsh Member of Parliament John Guest, who owned Dowlais Ironworks in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. The Dowlais Ironworks company was in operation until 1987, and John had taken over the company from his father. The marriage raised eyebrows among the elite, as despite John’s vast wealth, he was seen as inferior in comparison to Charlotte’s family. Furthermore, when the couple married, Charlotte was 21 and John was 49.

Regardless of public opinion, the pair seemed happy together and had ten children, many of whom went on to be successful in their own right. After moving into a mansion in Merthyr Tydfil, Charlotte immediately turned her attention to charitable activities, namely improving the lives of the working class and the betterment of conditions for workers in the Ironworks.

Similarly, Charlotte’s enthusiasm for languages and the arts never faltered. She passionately campaigned for the endorsement of Welsh literature and culture. Charlotte had mastered the Welsh language and set out to translate the Mabinogion with an assembled team of other scholars. The Mabinogion is a collection of folklore and mythology recorded in Middle Welsh throughout the 12th and 13th centuries, but is rooted in much earlier spoken narratives.

Charlotte’s translation in both Welsh and English was published in volumes between 1838 and 1845. In 1877, two years after Charlotte’s death, a revised edition of her work was published, which made the Mabinogion widely known for the first time. Additionally, her translation was the standard until 1948.

During the 1840s, John Guest declined in health, and Charlotte ran the business until their son could assume his father’s position. John died in 1852, and Charlotte married a scholar and her son’s tutor, Charles Schreiber, 14 years younger than her. Although this decision was unpopular among many of Charlotte’s friends in high society, she enjoyed traveling with her husband all over Europe.

Upon Charlotte’s death, aged 82, she left the artifacts accumulated from her excursions in her will to the Victoria and Albert Museum. Charlotte also survived Charles and maintained her dedication to philanthropic endeavors until the end. On the couple’s estate, Charlotte established a project to construct quality housing for those who worked on the estate. Two cottages were built before her death, but the initiative was continued by her daughter-in-law, who saw the completion of 111 cottages.