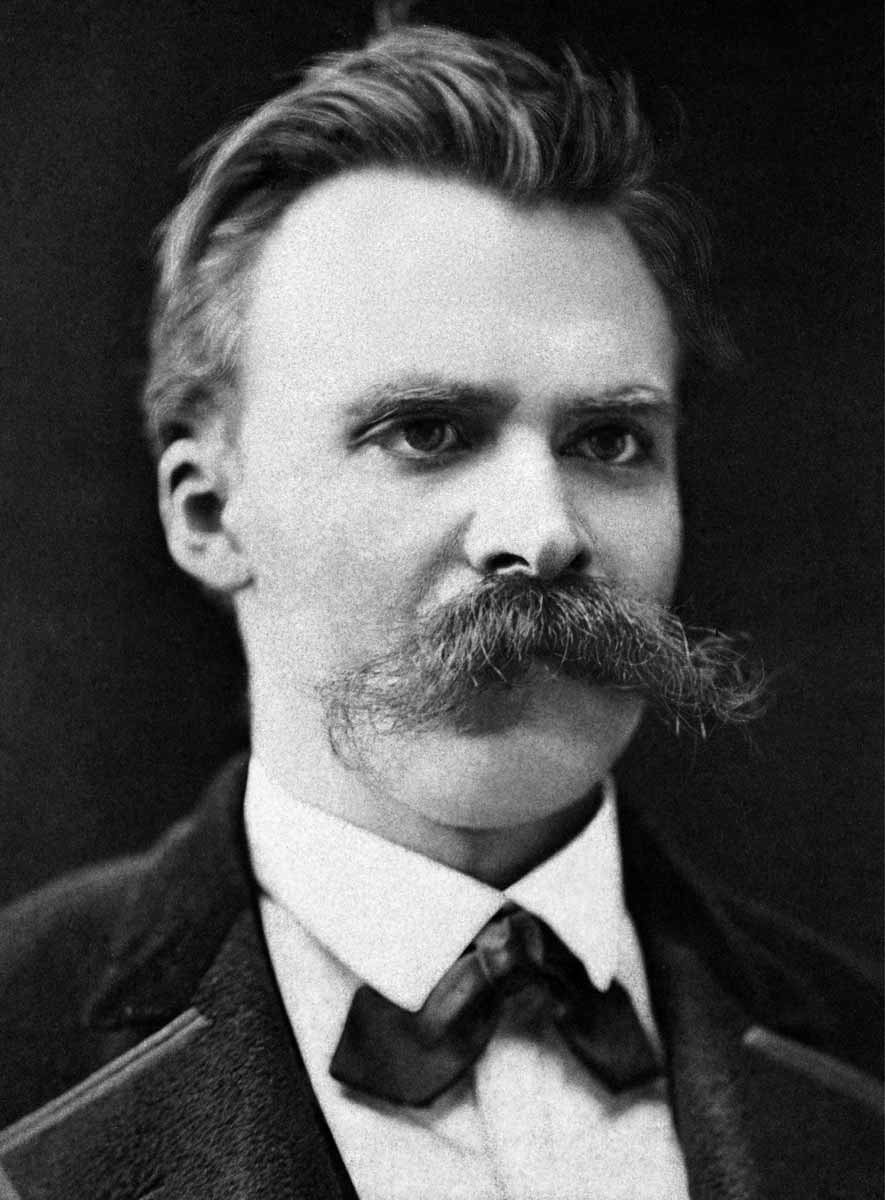

Nietzsche’s complex, occasionally baffling sense of humor usually entertains, sometimes enlightens and often perplexes his readers. Scholars are often divided over whether or not Nietzsche is at times joking or serious. His being no stranger to comedy, we would expect Nietzsche to recognize a philosophical joke. But what if a joke made by Socrates flew completely over his head? Ordinarily this wouldn’t be too troubling, but Nietzsche bases his entire criticism of Socrates on his interpretation of what might turn out to be a joke!

Nietzsche Was No Stranger to Humor

An appreciation of the tragic and the comic are fundamental to Nietzsche’s philosophy. For him, a strong sense of tragedy and comedy as complementary dispositions towards life are essential for human flourishing. We see in his philosophical works a keen interest in those aspects of life in which any line separating the two is blurred. That is, what fascinates Nietzsche are situations in which there can be felt a strong sense of both the tragic and the comic. Can there be a better example of this than Socrates, condemned to death, making a joke as he prepares to drink the poison that will end his life? We will take a look at Socrates’ joke in detail later but before we do let’s take a closer look at Nietzsche’s understanding of the relationship between tragedy and comedy and the role played by laughter.

Contrary to its usual association with destruction, suffering and distress, when expressed in the arts, tragedy can bring forth great insights concerned with the meaning of life as well as make the most profound inquiries into the human condition. Nietzsche appreciated the joy to be found in tragedy and took his inspiration from the Ancient Greeks, their theater in particular.

The tragic heroes onstage are fated to destruction. The stories of Antigone, Oedipus, Prometheus (seen below), for example, are all tragedies. However, their stories also reveal the beauty of life and show that human existence is meaningful. In a world that can sometimes seem meaningless and arbitrary, filled with pointless and inexplicable suffering, what happens to the characters on stage makes sense, appears significant and their actions justified. The Greek theater-goers could apply to their own lives the lessons learned from what they saw played out on the stage. Nietzsche argues that we can do the same.

Myths & Demands for Meaning

Like the heroes on the Greek stage we too face inevitable destruction. All of us are fated to die and we know it. This is the human condition. It is the way life is and an essential part of what it is to be a human being. Nevertheless, although life must end in death it can still hold meaning and be worthwhile. For Nietzsche, one of the most essential demands we can make of life is that it has meaning for us. Devoid of meaning, or purpose, human life would mainly consist of unjustifiable suffering.

It is undeniable that much of life involves suffering. Like death, suffering is an inextricable aspect of the human condition. However, according to Nietzsche it is not the existence of suffering itself that is the problem; what makes life unbearable is meaningless suffering. In The Genealogy of Morality he writes that the typical person “does not deny suffering as such: he wills it, he even seeks it out, provided he is shown a meaning for it, a purpose of suffering” (GM III, 28). Looking back at the Greek theater, we can see that the tragedies revealed a meaning and purpose for the suffering of the mythical heroes whose lives were played out before the audience. In other words, myths give meaning to their life.

Overcoming Silenus

The stories told on the Greek stage were invariably drawn from their mythology. All Greek myths, according to Nietzsche, are primarily attempts to overcome the so-called wisdom of Silenus. Depictions of Silenus vary in the mythology. Sometimes he is a satyr, with the legs and tail of a horse, but in other places he is shown accompanied by satyrs without being one himself. He can be depicted as a slight old man or an enormous pot-bellied drunkard (see above). Most often we see Silenus as a follower and companion of the god Dionysus. It is his position, between the gods and men coupled with his ability to communicate with both that allows us mortals access to his wisdom. In the story that captured Nietzsche’s imagination, Silenus is forced by King Midas to reveal his wisdom. In other words, to reveal secrets known only to the gods. In The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche paraphrases Silenus’ response as follows:

“Suffering creature, born for a day, child of accident and toil, why are you forcing me to say what is the most unpleasant thing for you to hear? The very best thing for you is totally unreachable: not to have been born, not to exist, to be nothing. The second best thing for you, however, is this: to die soon” (BT, 3).

The message from Silenus is clear: human life is not worth the suffering. There is no purpose or meaning behind it that could justify life itself. Put bluntly, we would all be better off dead. When Nietzsche says that all Greek myth is an attempt to overcome Silenus, what he means is that Greek myth is an attempt to show that life itself is meaningful and worth the suffering. In other words, to prove Silenus wrong: life is not a burden that all human beings ought to rid themselves of as soon as possible.

The Value of Life Itself

It is important to bear in mind that we are talking about “life itself.” Not personal lives particular to individual people. Unfortunately, it can often be the case that as far as some people are concerned their own lives are not considered worth the suffering of continued existence. For example, someone facing the rest of their lives in tremendous pain may choose euthanasia. Another person might choose to lay down their lives so that others can live. Martyrs sacrifice their own lives because they believe the lives of others to be of the highest importance. In these cases of suicide and self-sacrifice it is not “life itself” that is judged not worth living but a particular life, lived in particular circumstances.

In fact, when a person takes their own life because it fails to match up to what they think a good life should be, or when someone sacrifices themselves in order for others to live, in both these cases the value of life is affirmed. The judgement in the first case is that life in general is good and worthwhile but unfortunately this individual’s own life is pointless and bad. In the second case, the judgement is that life itself is good, and the desire is for others to continue to live and get the benefit of it. If someone were to commit suicide because they agreed with Silenus that all human life is not worth the effort, regardless of individual circumstances, this would be a very unusual suicide indeed.

The Question of Suicide

Albert Camus, in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, explored this subject in response to Nietzsche, and suggests that no-one has ever chosen death because they considered life itself to not be worth living. At the end of the essay he offers his own version of the Sisyphus myth in order to show that life itself is worth living. Sisyphus is a tragic hero, fated to spend all eternity rolling a rock up a mountain only to see it roll back down again just before he reaches the summit. Camus, in his telling of the myth, concludes that “all is well” and that “we must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

It is important to remember that the question is never really one of actual suicide. When Camus, for example, said the most important philosophical question is suicide, he did not think people were sitting around wondering whether or not they ought to end their lives because life itself simply is not worth the effort.

What is really at stake is the idea of life itself having value. If it is believed that human life has no intrinsic value, that only lives lived in particular ways by particular people are valuable, what does this belief tell us about taking other people’s lives or using other people’s lives for our own ends? Murder and slavery are despised as evils because these acts deny the value of all human life. The concept of human dignity, notoriously difficult to define, fundamentally rests on the idea of human life itself being valuable. For us to hold that such a thing as human dignity exists, we must show that Silenus is wrong and life itself is valuable. Let us return to Nietzsche.

Nietzsche’s Formula for Greatness

The question, posed by myth and answered by myth, is whether life itself is a good thing or a bad thing that we would be best to rid ourselves of at the first opportunity. For Nietzsche, how we approach life, whether we see it as something valuable, is a basis upon which we can be judged. He believed that great people love life and we ought to follow their example. But those who hate life and do not see its value ought to be removed from society (TI ‘Skirmishes’ 36).

In his philosophical biography, Ecce Homo, Nietzsche spelled out his “formula for greatness” which is amor fati or love of fate (EH ‘Clever’ 10). Great individuals, for Nietzsche, are the real-life counterparts to the heroes seen on the Greek stage. All human beings, like these characters on stage, have a tragic fate but those individuals that not just accept their fate but love their fate reveal the meaning and beauty of life. Nietzsche says that by doing so, great people say “yes” to life.

In his book The Gay Science, originally published in German as Die fröhliche Wissenschaft and sometimes translated into English as The Joyous Wisdom, Nietzsche associates a love of one’s fate with saying “yes” to life (GS 276). Put simply, to be joyful is to accept life and everything in it, the tears and the laughter. And one can only achieve this by believing that life itself is worthwhile. This is Nietzsche’s most fundamental message. Inextricably wrapped up in this joyous attitude is laughter. Let us now take a brief look at Nietzsche’s thinking on the subject.

Nietzsche’s Philosophy of Laughter

We saw above that Nietzsche talks of joy in terms of accepting “the tears and laughter” that come with life. In Nietzsche’s philosophy, the ability to laugh, in the right way, is essential to a positive disposition towards life and the human condition. He argues that it was because the human condition is marked by such profound suffering that laughter was “invented.” Without the ability to laugh we would probably not have survived as a species. Human beings are, Nietzsche says, the most unhappy and melancholic of all the animals but also capable of being the most cheerful (WP ‘European Nihilism’ 91).

Cheerfulness and a positive disposition towards life is dependent upon the ability to laugh. However, the ability to laugh, especially at oneself, is for Nietzsche something only the very gifted are able to do. This is because, according to him, to be able to truly laugh at oneself “as a human being” one would first have to discover the whole truth about the human condition. This is something Nietzsche believes no-one has as yet been able to do. And the emergence of such individuals is a long way off. “Laughter,” he says in The Gay Science, “has a future” (GS 1).

In Nietzsche’s philosophy, the future for human beings is dependent upon the emergence of great individuals capable of laughter. Nietzsche was no “equal opportunities” philosopher. He believes that human greatness is only possible through the inspirational leadership of an elite group of geniuses. Looking around him, he saw that laughter and gaiety was held, if not in contempt exactly, but to be considerably less worthy than what we might call “seriousness.” In order for the masses to be inspired by the laughter of great individuals they must first come to value this kind of laughter.

Saying Yes to Life

When we think of something important, we often say that the matter ought to be “taken seriously.” Nietzsche considered this way of thinking as a prejudice to be overcome (GS 327). When criticizing the educational establishment of his native Germany, he remarked that it lacks “laughter of higher men” (GS 177). We can see that Nietzsche does not hold the “wise and educated” men of his society in high esteem. Something, we shall also see, he shares with Socrates.

What is important to grasp here is that, for the benefit of humankind as a whole, Nietzsche is looking for great geniuses that say “yes” to life and who are capable of the kind of profound laughter that only someone that really understands the human condition is capable of. Such people are rare and any threat to their emergence must, for the sake of humanity, be eliminated. In other words, “nay-sayers” must not be allowed to jeopardize the flourishing of “yay-sayers.” Socrates, for Nietzsche, was a nay-sayer and a major threat.

In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche claims to be the “opposite of a nay-saying spirit” because he is the “bearer of glad tidings” (EH ‘Destiny’ 1). The religious tone is deliberate. Ecce homo, “behold the man” in Latin, are the words used by Pontius Pilate in reference to Jesus. Nietzsche’s text is a biography of sorts, so when he tells us to “behold the man” the man in question is himself. He is figuratively comparing himself to Jesus. In addition, the word gospel literally means “good news” or “glad tidings.” By speaking of himself as the bearer of glad tidings, Nietzsche is making an allusion to the Gospels.

A Religious Quest?

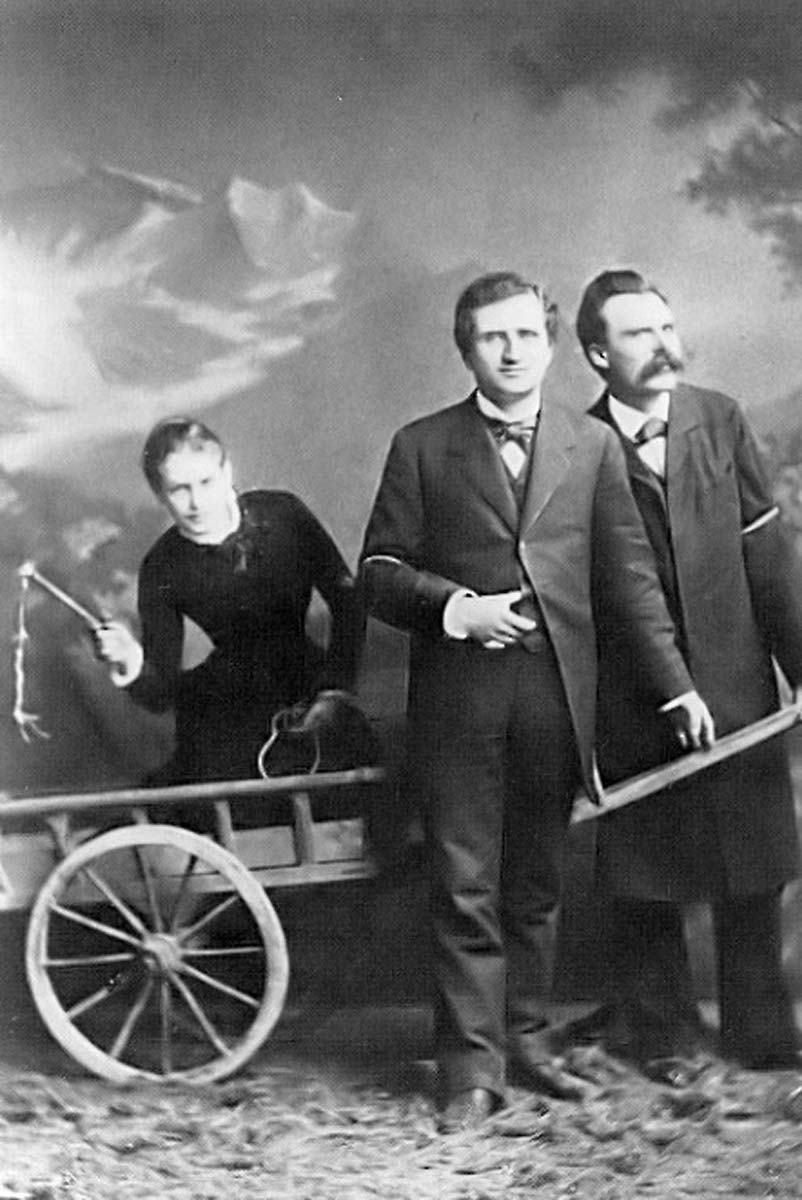

Nietzsche, an atheist, is attempting to offer an alternative to the Christian understanding of life and the belief that there exists a “better life” after death. His good news is that this life is good. With this belief, he contrasts himself not only with Christians that claim that there is a better life to be had after this life but also with so-called “wise men” and philosophers who argue that life is meaningless, purposeless and no good. We would not go far wrong if we were to say that Nietzsche’s philosophy is the product of a religious quest he imposed upon himself. We would go very far wrong, however, if we went on to suggest that this quest was motivated by a belief in God! The point is worth making because the idea of pursuing a religious quest is something, as we shall see, Nietzsche shares with Socrates. It also helps us understand what Nietzsche has against Socrates.

In Twilight of the Idols, in his reflections on “The Problem of Socrates,” Nietzsche begins by saying: “The wisest men in every age have reached the same conclusion about life: it’s no good…” (TI ‘Socrates’ 1). The rest of the chapter is dedicated to one wise man in particular: Socrates. Nietzsche does not disapprove of the Greek philosopher because he undertook a religious quest but because, in his interpretation, the “good news” Socrates offers is not that life is good but that life is a burden we are better off without. “Socratism,” in Nietzsche’s view, is a dangerous nay-saying philosophy.

Is Nietzsche correct that Socrates is against life? His strongest argument rests on what the Greek philosopher has to say moments before death by poison. But what if Socrates wasn’t “nay-saying” but actually making a joke? Let us turn now to Socrates and begin with a brief overview of how he ended up with a cup of poison in his hand at his execution.

Socrates is Condemned to Death

Why was Socrates sentenced to death? In Plato’s Apology of Socrates we are told that Meletus, an Athenian prosecutor, brings the suit against him, accusing Socrates of being “a criminal and a busybody” (Plato, Apology 19b). The particular charges are twofold: impiety, that is, a failure to acknowledge the gods that were acknowledged by the city; and the corruption of the youth of Athens. The most detailed account we have of the trial, as well as of Socrates’ life and philosophy in general, comes from his former student Plato. Born of an aristocratic and politically influential family, Plato was exactly the type of young man the Athenian establishment would not want to be hanging around a man like Socrates.

Socrates was poor and ugly at a time when physical ugliness was almost considered a moral failing. But he was also a war hero and an extremely clever speaker and philosopher. He was popular with a lot of people who loved to hear him philosophizing with/against others. Against others? Nietzsche credits Socrates with inventing a new way of doing philosophy that was almost like a combative sport (TI ‘Socrates’ 8).

Socrates loved to approach respected individuals in Athens—in particular those widely considered to be knowledgeable and wise—in order to pose seemingly simple questions these great brains could not answer. For example, in The Republic we see various supposedly wise men hold forth on justice but when asked cannot tell Socrates what justice is exactly. It is easy to see why a lot of people in Athens would find the spectacle of these men being stumped by Socrates amusing. However, it is also easy to see that the rich and powerful would not take kindly to being made to look like fools.

Piety or Disrespect?

It was this combination of Socrates making powerful people look stupid and of the public enjoying him doing so that is most likely the reason he found himself on trial for his life. His enemies were particularly concerned about how well respected Socrates was in the eyes of the young men destined to one day become the leaders of Athens. The worry was that his teachings would undermine respect for authority in Athens and perhaps even respect for Athens itself.

As mentioned above, his formal charges were failing to acknowledge the gods of the city and corrupting the youth. Plato considered these charges to be trumped-up. In his various dialogues his aim is to show how brilliant his former teacher actually was. In the Apology, Plato shows Socrates to be on a religious quest when he was questioning the people of Athens. Far from failing to acknowledge the gods, for Plato his teacher was honoring one of the most respected gods of the city: Apollo.

According to Plato, it all begins with a visit to the Oracle at Delphi. Here people could ask questions that would be answered by Apollo, through the intercession of the sibyl and the interpretation of the priests. Chaerephon, a friend of Socrates, asked the oracle if there was anyone wiser than Socrates. And the answer came back that no-one was wiser (Apology 21a).

When Socrates hears this, he is confused: surely, he thinks to himself, there must be someone wiser than him, after all, he does not know anything. But if this is the case, Apollo is either lying or mistaken and neither of which can be possible. Deeply unsettled, Socrates feels compelled to investigate what he sees as a great riddle (21b).

Socrates Search for Someone Wise

Socrates begins his quest by trying to find someone wiser than he. First, he approaches “the public men.” These include the politicians and public speakers famed for their intelligence. Surely one of these fine brains could easily prove themselves wiser than he? However, to his astonishment, Socrates discovers that none of these celebrated men have any wisdom at all. In fact, those with the best reputations turned out to be the most deficient (22a). Respected men of law could rattle off great thoughts in fine words on what ought to be done and with apparent authority. But, as mentioned above, when questioned by Socrates on the basics they were stumped and could not answer.

Frustrated, Socrates changes tack and approaches the poets. One of these great artists must surely be wiser than himself. He discovers, though, that while the poets can produce great poetry, these works are inspired by the gods and the artists themselves are mere conduits for divine wisdom. The problem is everyone—including, unfortunately, the artists themselves—falsely believes the artists to have special insights into their works. Socrates is disappointed to learn that when it comes to interpreting and understanding poetry and art, poets and artists are no better than anyone else (22c).

Finally, in his quest to find at least one person wiser than himself, Socrates turns to the artisans and hand-workers. One of these fine men must be wiser than he because, as Socrates is very willing to admit, what he knows “is practically nothing” (22d). Artisans must know a thing or two because without knowledge of their respective crafts how could they produce anything? The problem Socrates encounters, however, is that while each individual artisan has good knowledge of their own craft, they mistakenly believe their expertise extends to all other areas of life. In other words, on most matters they rest on the false assumption they know what they’re talking about when they do not (22d).

The End of the Search

Socrates finally has the answer to his riddle. He wanted to know how a man who “knows nothing” could be wiser than anyone else. It turns out all those famed and celebrated for their intelligence and expertise had one thing in common: they all believed they had wisdom when in fact they did not. The difference, therefore, between Socrates and everyone else was that while no-one actually knew anything, he knew one thing: that he didn’t know anything! That small piece of wisdom meant that he, Socrates, was the wisest man in Athens.

Now, whether or not Socrates actually believed himself to be on a religious quest is debatable. However, it will be quite clear to everyone that his going around making powerful people look stupid is not going to end well. And, as we know, Socrates ends up in court facing the death penalty.

At this point in the story, it is not obvious what problem Nietzsche might have with Socrates. To see this we will have to fast forward to the time of his execution.

The chosen method of execution is death by poisoning. At the appointed time, Socrates is given a cup of hemlock to drink. This would have been prepared by grinding up the seeds of the hemlock plant which are then added to wine with possibly a few other ingredients thrown into the mix. This concoction would have been carefully measured out and prepared as a precise dosage by the executioner. How might one feel to be given this cup and told to drink its contents? Plato tells us in Phaedo that Socrates took the cup “in a cheerful way” (Phaedo 117b) and that after a few words, “he took the cup to his lips and, quite readily and cheerfully, he drank down the whole dose” (117c). It is these few words that interest us because they contain what may be a joke that flew over Nietzsche’s head.

Socrates’ Final Joke

Plato tells us that when Socrates is handed the cup he asks the executioner what he has to do. He is told to drink the contents and to walk around until his legs get heavy. Socrates accepts the cup “in a cheerful way” and then asks if he can pour a libation. If he is making a joke, here it is.

Now, it must be taken into account that in order for a joke to sound funny you generally should avoid a four thousand word build-up before telling it! However, in this case, it could not be helped. So apologies to Socrates if in the telling of this story I inadvertently kill the joke.

A libation is a ritual in which the liquid from a cup, usually alcohol, is poured out onto the ground in honor of a god or gods (or sometimes in memory of the dead). The word “libation” has its origins in the latin libatio, to pour. It was common in Socrates’ time for the first drink of a drinking session to be poured out as a libation.

So, we can picture the scene: Socrates in his cell, surrounded by his friends and a slave has been sent to fetch the executioner. The man arrives with the poison and after some brief instructions hands the cup over to Socrates. Socrates takes the cup cheerfully and quips “What do you say about my pouring a libation out of this cup to someone?” In other words, after being handed the poison, he suggests pouring it out onto the floor in honor of the gods. Bear in mind here that he is being executed, in part, for failing to acknowledge the gods! Obviously, he is told no and Socrates suggests offering a prayer instead. His last words to his friend Crito is a reminder of his promise to offer a prayer and a callback to the joke. In Phaedo we read: “‘Crito,’ he said, ‘We owe a cock to Asclepius. Pay it and do not neglect it’” (118a).

No Laughing Matter for Nietzsche

For the Greeks, Asclepius was the god of medicine. The image of his snake-entwined staff is still in use today and often seen in hospitals and pharmacies around the world. The cock Socrates “owes him” is a rooster that Crito, on his behalf, will sacrifice in Asclepius’ honor. Why did this upset Nietzsche so?

It is the giving thanks to Asclepius that Nietzsche takes umbrage with. As we have seen, he is the god of medicine and traditionally the Greeks gave thanks and made sacrifices to him because of the healing he offered. By offering thanks to Asclepius, Socrates is effectively saying the cup of poison is medicine and his death is a cure. But if death is the cure, what is the sickness? It can only be life. According to Nietzsche, Socrates thinks that poison is medicine that will cure him of the sickness of life and is thankful to Asclepius for his help. Socrates, then, is for Nietzsche no philosopher of life but a philosopher of death. He does not say yes to life but no. Socrates is a “nay-sayer” and, for Nietzsche, only “yay-sayers” are capable of greatness.

Nietzsche was concerned with humanity’s future whose fate he believed rested in the hands of great people. He thought these very rare individuals only emerged by chance and that everything ought to be done to encourage their emergence and to help them flourish. They are the ones capable of loving their fate, loving life and of profound laughter in the understanding of the human condition. They are, in short, those who say “yes” to life. Socrates, however, was a nay-sayer. His philosophy, according to Nietzsche, is a threat to the emergence and flourishing of great people because his philosophy teaches us to reject life. Life, for Socrates, is as it was for Silenus, a burden we are best to rid ourselves of. And, in Socrates’ case, cheerfully.

A Puzzle Left to Solve

Socrates did not publish any works. Most of what we know about his philosophy comes from the dialogues written by his student Plato. These texts have become some of the most important in the entire Western philosophical canon. A remark, often quoted, by the famous philosopher and mathematician Alfred North Whitehead is that “All of Western Philosophy is but a footnote to Plato.” The enormous influence of Socrates is something that Nietzsche saw as a great threat to humanity because of the nay-saying of his philosophy. Was he correct? Was Socrates the “nay-sayer” Nietzsche believed him to be or was he, in fact, accepting of his fate and making a joke that went over Nietzsche’s head?

It is a puzzle left for us to work out. However, we must bear in mind that the “Socrates” we see here is not the man himself but two versions of him: one created by Plato and another by Nietzsche. We will never know the truth of what actually happened on the day of his execution but that is not the most important thing to think about here. Socrates’ “joke”—if indeed he actually made one—lies at the heart of a clash between two opposing philosophies of life, one that says “yes” and the other that says “no.” Exploring this key episode in the history of Western philosophy exposes in a powerful way the radical differences in two distinct attitudes towards life and the human condition.

Abbreviations of Nietzsche’s Works

I have used the following translations of Nietzsche’s works, referring to them with the following abbreviations.

BT Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Birth of Tragedy. Edited by Douglas Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2008)

EH Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols. Edited by Aaron Ridley and Judith Norman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2005)

GM Nietzsche, Friedrich. On The Genealogy of Morality. Edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2017)

GS Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Edited by Bernard Williams. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2013)

TI Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols. Edited by Aaron Ridley and Judith Norman. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2005)

WP Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Will to Power. Edited by R. Kevin Hill. Penguin Classics (2017)

For Plato’s dialogues, The Apology of Socrates and Phaedo

Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler; Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966.