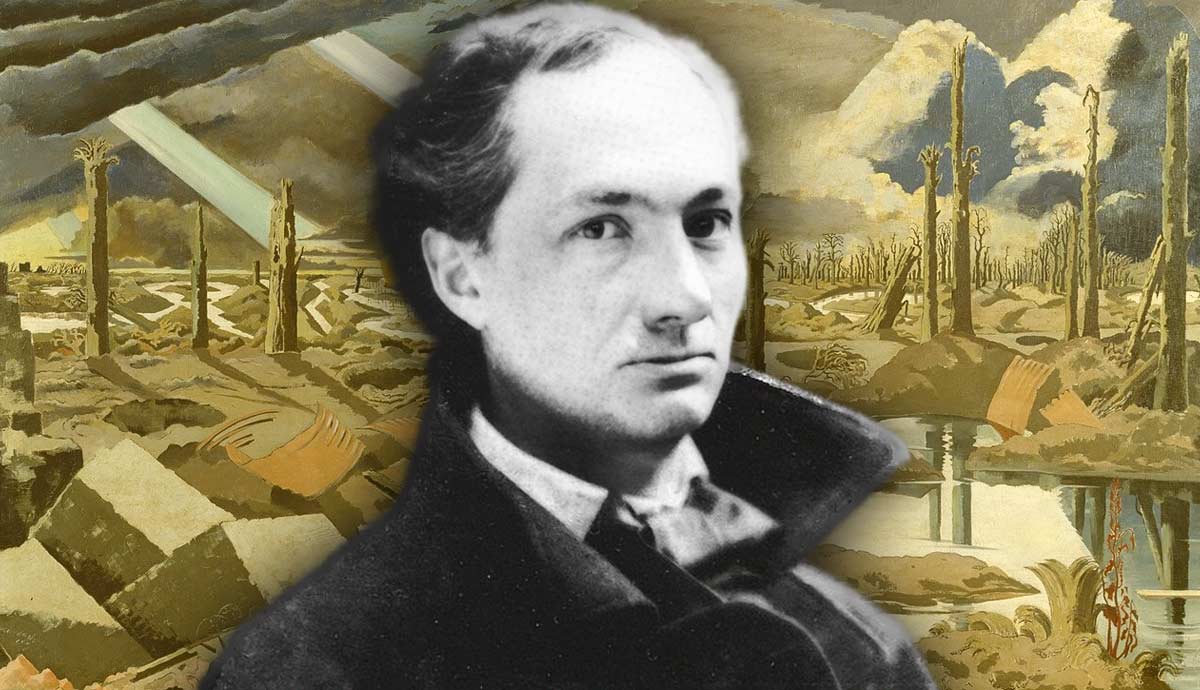

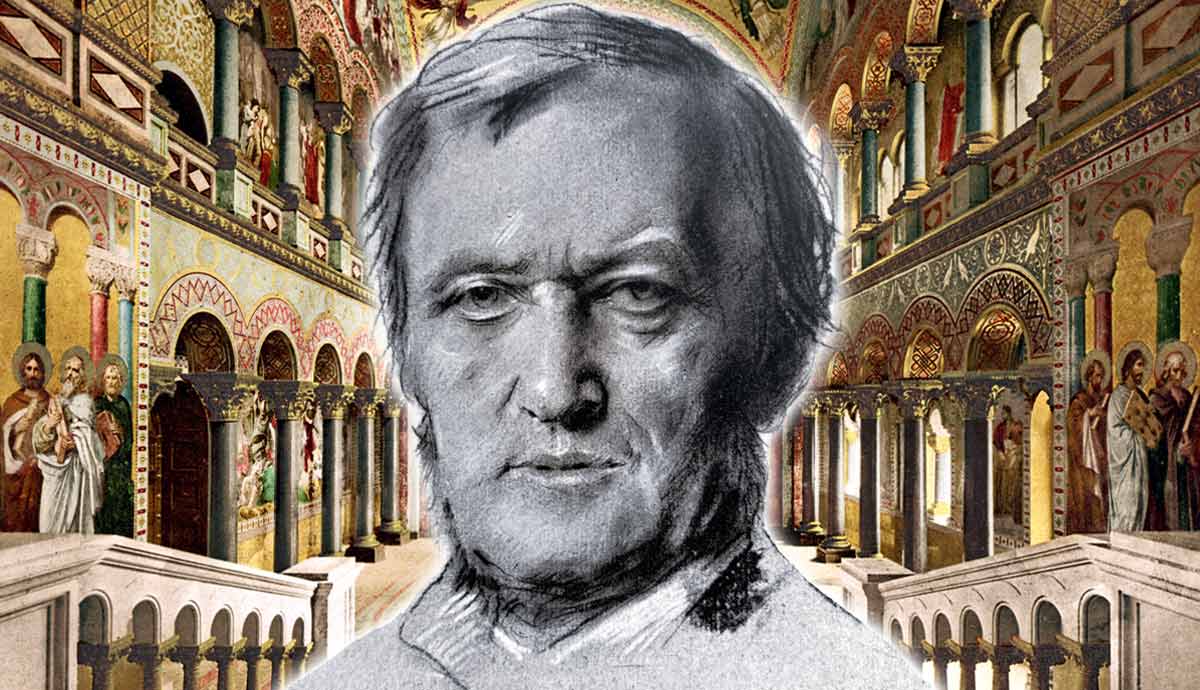

In the music world, Richard Wagner’s influence was vast, stretching beyond the confines of the opera houses. He innovated the leitmotif, a repeated musical theme associated with a character or idea, which is used in film and television music today. His moves toward atonality influenced the modernist composers of the early 20th century. His technique of unending melody reconfigured how composers might think about structure and form. But Wagner also caught the attention of artists in other media, possibly more than any composer before or since. How did Wagnerism manifest in the other art forms?

Richard Wagner in the Visual Arts

From The Flying Dutchman to Tristan and Isolde and Parsifal, Wagner’s music dramas had a highly visual element. The term ‘music drama’ is often used instead of ‘opera’ for Wagner’s works precisely because they combine visual and literary elements with music. Wagner also had firm ideas about the stage design and choreography of his productions. It was only natural that these visual spectacles would influence artists working in visual media, such as painters, illustrators, sculptors, and designers.

One early Wagner-infused art movement was Impressionism. The German composer’s music was not frequently performed in France in the 1870s, not least after the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71 soured relations and made German music unpopular. Nevertheless, some artists became card-carrying Wagnerites in these years. Espousing Wagner’s cause became a way for artists to signal their transgressive or anti-establishment values.

Claude Monet, Henri Fantin-Latour, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir all moved in Wagnerian circles, with Renoir painting a portrait of the composer in 1882. Fantin-Latour completed works depicting scenes from Wagner’s dramas, such as Les Filles du Rhin and Scène finale de la Walkyrie. Similarly, Paul Cézanne initially gave his Young Girl at the Piano (1868-69) the title Overture to “Tannhauser,” inspired by the growing popularity of the composer’s music.

Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin were both inspired by the rich harmonies in Wagner’s music, which seemed to open up new worlds and pave the way for new imaginings of color in painting. Gauguin was particularly attracted by Wagner’s anti-commercialism. The painter, who would eventually abandon Western civilization for what he considered a purer existence in Tahiti, agreed with Wagner that art had been corrupted by modern life.

In Britain, the Pre-Raphaelite artists often shared subjects with Wagner, both taking an interest in the medieval and Arthurian legends. Dante Gabriel Rossetti‘s oeuvre is full of femmes fatales like those Wagner put on stage—Brünnhilde in the Ring cycle and Kundry in Parsifal. John Everett Millais hosted a dinner in Wagner’s honor during the 1877 Wagner Festival in London (although the composer did not attend).

His wife, Cosima, sat for a portrait by Edward Burne-Jones, whose paintings were full of Wagnerian subjects: from Laus Veneris, which imagines the Venusberg as seen in Tannhäuser, to the Holy Grail tapestries he designed along with William Morris. Cosima Wagner had also hoped to meet Morris because of the extensive overlap between Morris and Wagner’s work. In his poetry, translations, illustrations, and designs, Morris took an extensive interest in Arthuriana and the Old Norse legends that had inspired the Ring.

Finally, the artist whose name was most persistently paired with Wagner’s in late-19th-century Britain was Aubrey Beardsley, the illustrator and writer. Beardsley’s drawing The Wagnerites (1894) offers a view of a typical fin-de-siècle Wagner audience. He also created drawings of Wagner characters such as Siegfried, Tristan and Isolde, Alberich, and the Rhinemaidens. His only novel, an unfinished erotic farce originally titled The Story of Venus and Tannhäuser, was a smutty send-up of the Wagnerian hero’s adventures in the decadent land of Venus.

Wagnerian Poetry

Much of Wagner’s influence on Impressionism in late-19th-century France came via writing about the composer rather than a great familiarity with his music. One of his first French acolytes was the poet Charles Baudelaire, whose attendance at a performance of Tannhäuser in 1861 resulted in a flurry of overwhelmed, overwrought writings—an article praising Wagner and an effusive letter sent to the composer himself.

Baudelaire declared himself utterly affected by the music, experiencing sensations unlike any he had ever known before, and (like Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s novel) disturbed yet intrigued to recognize something of himself in the music drama.

For Baudelaire, Wagner’s works were a perfect mirror of his own interest in synesthesia (uniting all the senses in one artistic experience) and the meeting of the sacred and profane. Other French poets would venerate Wagner for the same reasons: Symbolist and Parnassian poets who sought to return versification to its ancient association with music, such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Théophile Gautier, Catulle Mendès, and Paul Verlaine.

By 1885, French literature’s Wagner mania was consolidated in the Revue wagnérienne. This Paris-based periodical initially mirrored the Bayreuther Blätter, a German periodical publishing excerpts of Wagner’s writing, analyses of his dramas, and other related pieces. The Revue‘s co-founder, Éduoard Dujardin, was a devoted Wagnerite who later wrote a novel, Les Lauriers sont coupés (1887). This novel showed the influence of Wagner’s unending melody on literature. Indeed, Dujardin aimed to convey the inner workings of a character’s mind in long, winding sentences, prefiguring the stream-of-consciousness technique used by several 20th-century authors.

As for poetry written in English, Algernon Charles Swinburne—like Edward Burne-Jones—was influenced by Wagnerian subjects, creating his own Laus Veneris, a poem that revels in the pleasures and pains Tannhäuser experiences at the Venusberg. As one of Baudelaire’s most prominent champions in the Anglophone world, Swinburne was inevitably drawn to Wagner and attracted just as much censure as the French poet and the German composer.

Another controversial poet conceived of his endeavors as essentially Wagnerian. Walt Whitman‘s Leaves of Grass attracted criticism for its blend of high-flown ideas (the ego of the poet as a universe in itself), ordinary language, and freedom from rhyme or meter. Like the composer, he fixed his eyes on the future, completely re-envisioning the boundaries of the form he worked in and its capacities to encompass such weighty topics as love, death, and the self.

Wagnerian Fiction

Given the sprawling duration of many of Wagner’s music dramas, it is perhaps unsurprising that they influenced prose fiction with novels similarly expanding to hitherto unheard-of lengths in the late 19th century.

Émile Zola, along with his friend Paul Cézanne, was a member of a local Wagner Society in his youth. His Rougon-Macquart novels, a series numbering 20 in total, might be compared to Wagner’s Ring cycle. Indeed, both artists attempted to evoke an entire world in all its historical proportions.

By the beginning of the following century, Marcel Proust had embarked on his own Wagnerian venture with seven novels collectively titled In Search of Lost Time. Proust went even further in his imitation of the composer, weaving leitmotifs throughout his writing and aiming to do with his sentences what Wagner had done with his musical phrases.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Decadent novelists like Charles Baudelaire were captivated by Wagner’s hints of the mythic, esoteric, and occult. They were particularly influenced by the Bühnenweihfestspiel (sacred festival play) Parsifal, in which the Grail Knights perform a ceremony resembling the Christian Eucharist. On the other hand, the play’s themes of redemption, sacrifice, death, and rebirth resonated with Buddhist thought.

The work’s dark intimations of Christianity, tinted with paganism and Eastern influences, appealed to Joris-Karl Huysmans, who wrote about Satanism in novels like Là-bas (1891) and La cathédrale (1898). However, he is best remembered for À rebours (1884), “Against Nature,” dubbed the “breviary of decadence.” À rebours was famously the novel that corrupts Dorian Gray in Oscar Wilde’s 1891 novel (although it is not explicitly named). The Picture of Dorian Gray similarly pays tribute to Wagner as something of a high priest of decadence.

Wagner did not style himself as a high priest of decadence, but one of his more eccentric fans did: Sâr Joséphin Péladan (‘Sâr’ meaning ‘king’ in Akkadian, an ancient Semitic language). Péladan founded the Order of the Catholic Rose et Croix, a movement derived from Rosicrucianism and characterized by a mixture of Christian mysticism, alchemy, and magic.

Péladan also wrote art criticism and novels, notably a 21-volume cycle called La Décadence latine. References to Wagner are dotted throughout the novels, but the most Wagnerian was The Victory of the Husband. In the story, a pair of lovers name themselves Siegmund and Sieglinde (after the incestuous siblings in the Ring cycle) and travel to Bayreuth, the home of Wagner’s music, where they make love during a performance of Tristan and Isolde.

Thomas Mann, Wagner’s compatriot, also wrote about characters being aroused by Tristan, notably in the 1903 novella of the same name. The figure of Wagner looms over Mann’s work, from the increasingly diabolical composer in Doctor Faustus (1947), who charts new territories in chromaticism, to the composer Gustav Aschenbach in Death in Venice (1912)—the city, incidentally, where Wagner died.

Before Death in Venice, Vernon Lee wrote the short story A Wicked Voice 1890, just a few years after Wagner’s own death in Venice. Lee’s story is about a Wagner-esque composer transfixed by hallucinations of a long-dead castrato’s voice and goes mad. James Huneker, the American writer and music critic, wrote several short stories featuring Wagner’s music as shorthand for decadence, madness, and eroticism. Like Péladan and Mann, the Irish novelist George Moore included Tristan and Isolde as a pivotal spur to eroticism in his novel about an opera singer, Evelyn Innes (1898).

Richard Wagner in the Theater

As the example of George Moore suggests, Wagner’s influence in late-19th-century literary Ireland was strong in the theater as well as in prose and poetry. W.B. Yeats, the foremost writer to emerge from this milieu, was a keen spectator of Wagner’s dramas (as was a young James Joyce). Yeats, along with Moore and Edward Martyn, founded the Irish Literary Theatre in 1899, a venture inspired by the rising interest in Irish nationalism and the resurgence of Celtic culture at the time.

For Yeats, Wagner’s work was a blueprint. It was strongly aligned with German nationalism, but it also contained folkloric touches and was intertwined with Irish legend in Tristan and Isolde (whose heroine hailed from Ireland). The plays Yeats wrote and presented with the Irish Literary Theatre were steeped in Wagner, transplanting his self-sacrificing heroines, doomed lovers, and Shadowy Waters (the title of one play) to an Irish context.

Other burgeoning theatrical movements took their cue from Wagner at the end of the 19th century. In Belgium, Maurice Maeterlinck innovated a Symbolist theatrical style that, similar to Symbolist poetry, took inspiration from the correspondence of words, music, and mysticism in Wagner’s works. His 1892 play Pelléas et Mélisande was a tale of forbidden, doomed love, like Tristan and Isolde. It was later set to music by a composer who had himself been, if briefly, under the spell of Tristan: Claude Debussy.

English theater’s most committed Wagnerite was another Irishman, George Bernard Shaw, who saw the music dramas as embodiments of his socialist ideals. Most notably, the Ring cycle struck Shaw as an indictment of capitalist greed and a valorization of the ordinary man as a hero. Shaw channeled these ideas into his own plays. However, his most overt statement of Wagner’s influence is the critical work The Perfect Wagnerite (1898), which offers a reading of the Ring as a critique of the misuse of power.

Wagner’s influence on late-19th and early-20th-century theater extended to the buildings themselves. His creation of the Festspielhaus, or festival theater, at Bayreuth, had been a monumental feat of architecture in itself. Taking inspiration from Greek amphitheaters, the theater at Bayreuth was constructed differently from any other theater in the 19th century, with all seating angled towards the vast stage in a fan shape (rather than with theater boxes facing each other, as in the conventional less egalitarian, horseshoe shape). Wagner meticulously constructed the building to optimize the theatrical experience in every aspect: sight, sound, and sensation.

Architects in America, in particular, took their cue from Wagner and Bayreuth. Around the turn of the 20th century, the Chicago School aimed to imitate Wagnerian grandeur in its buildings. For example, the city’s opera house imitated Bayreuth’s fan-shaped seating and had an icon of Wagner above the proscenium to signal that he was one of the theater’s guiding spirits. Architects of the Gothic Revival in Boston and New York City also explicitly executed Wagnerian plans for buildings that they hoped would be grandiose and democratic.

At the other end of the scale—a building steeped in Wagnerian influences but meant for the enjoyment of just one person—was Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, Germany. Its creator and financer, King Ludwig II, was also a devoted patron of Wagner. Indeed, Ludwig II’s patronage had been the only way that the composer, perpetually in debt, had managed to stage his ambitious works.

Ludwig began building Neuschwanstein with an architect and a stage designer in 1869. Although it was never completed to fully match his vision, and the king died in mysterious circumstances before he could live there, the castle boasts an array of Wagnerian interiors. These include a throne room with murals depicting the Grail procession from Parsifal and a grotto inspired by Tannhäuser—a lasting monument to Wagner’s huge influence on all corners of late-19th-century culture.