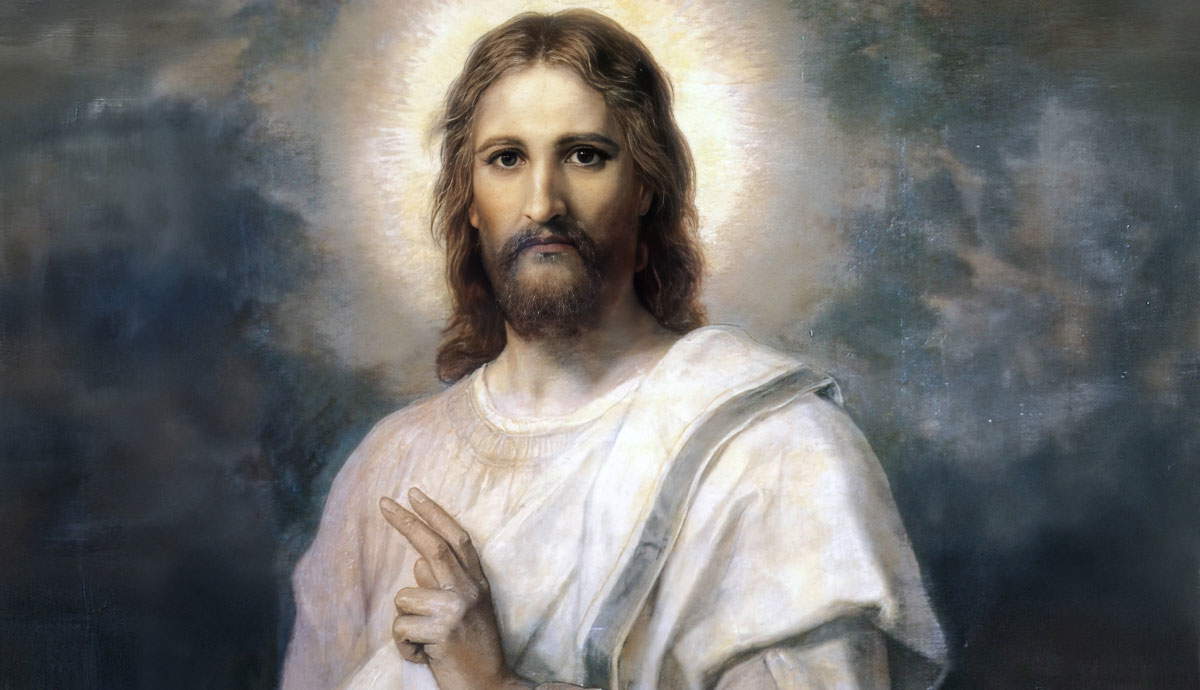

Many of the world’s priceless or most valuable works of art have been housed in museum collections under lock and key for hundreds of years, and it can be difficult to estimate just how much they are really worth. On the other hand, there are a rare few near priceless masterpieces that make their way into auction houses for sale. Of them all, there is currently one work of art that has sold for the highest price in history: Salvator Mundi, by Leonardo da Vinci, 1490-1500. This is the story behind the world’s most valuable artwork, sold for a cool $450 million at a Christie’s auction in 2017.

The Salvator Mundi: Sold During a Tense Auction

Da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi went on sale during a tense, drama-filled auction which Scott Reyburn, critic for The Art Newspaper, described as ‘nonsensical.’ After just 18 minutes of tense competition between some of the wealthiest buyers in the world, the painting reached an incredible $450 million, making it the most valuable artwork ever to be sold on the open market. Reyburn described the moment when the final, highest bids came in, observing how “the audience gasped and whooped as if they’d just seen a rocket explode high above their head.”

The Painting Was Bought by Mohammed bin Salman

A mystery buyer acting on behalf of Mohammed bin Salman, the crown prince of Saudi Arabia, was the highest bidder for the Da Vinci masterpiece. This means that the painting is now in the ownership of the Saudi Royal Family. Rumor has it Bin Salman paid such a staggeringly high price in order to ensure the prized artwork didn’t fall into the hands of the Qatari royals, who were also bidding at the same event.

Its Whereabouts Today Are a Mystery

Since its sale, the location of the world’s most valuable artwork has remained something of a mystery. Initial talks of housing the painting in the Louvre Abu Dhabi, or the Louvre in Paris, hung alongside Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, never materialized. Instead, the painting remained on bin Salman’s private luxury, 440-foot superyacht Serene for several years. When warnings came in that the seawater surrounding the yacht might have a corrosive impact on the painting, news later emerged in a 2021 report suggesting the painting has been moved to a private location somewhere in Saudi Arabia.

Yet its whereabouts are still unknown, which has been cause for concern amongst art experts. Dianne Modestini, a professor at New York’s University Institute of Fine Arts, who carried out extensive restoration work on Salvator Mundi, called the painting’s virtual disappearance ‘tragic’, commenting, “To deprive the art lovers and many others who were moved by this picture – a masterpiece of such rarity – is deeply unfair.”

It Might Not be a Real Leonardo

The Salvator Mundi has been the subject of fierce debate over the years, with many doubting its validity as a real Leonardo. In fact, several art experts came forward following the artwork’s extortionate sale price, arguing that the painting was a “studio work” in which Leonardo’s actual participation would have been insignificant – instead, they argue Da Vinci handed the completion of the entire work over to his studio apprentices. If this were the case, the market value of the most valuable artwork would be significantly lower than originally thought. Meanwhile, some recent reports argue that Da Vinci may well have painted the head and shoulders of Christ, while the hands and arms are of a different artist.

The Painting Is Known as the ‘Lost Leonardo’

The Salvator Mundi is known as the ‘Lost Leonardo’, due to its long disappearance, and it became the subject of a documentary film of the same name in 2021. As the film explains, the painting has a long history; historians believe Da Vinci took on the commission for the work in around 1500, for Louis XII of France. In 1625, the painting was purchased by Charles I of England, but by 1600, its whereabouts were no longer known. The painting reappeared in the 20th century, and at that time it was attributed to Bernardino Luini. Later, the painting popped up at a New Orleans auction in 2005, when it was labelled as “after Leonardo.”

Art dealers Alexander Parrish and Robert Simon purchased the painting, and wondered if the painting might be a ‘sleeper,’ meaning by an artist much more high profile than initially thought. The painting they bought had suffered significant damage and overpainting, so they took it to Modestini, who was the first to claim the painting was original. Following her extensive work, she took the painting to Luke Syson at London’s National Gallery, who, along with a team of experts, believed too that it was a true Leonardo. From here, the painting passed into the hands of Yves Bouvier, from where it eventually made its way to the much hyped auction at Christie’s.