Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome is where the marble sculpture Pieta (the visual trope of the Virgin Mary holding the deceased Christ) by Michelangelo is housed. This work is known for its realism, a factor made even more impressive by the fact that it was executed in marble. The technique of transforming large rocks extracted from the earth and chiseling them into replications of the human form finds its influence in prior centuries through the art of Ancient Greece and Rome. Many artists continue to look at this period for influence.

Marble Sculpting Techniques

Sculpting from stone is an art form that existed as far back as 3000-2900 BCE in the town of Warka in Ancient Sumer (modern Uruk between modern Saudi Arabia and Iraq on the Persian Gulf). The marble Mask of Warka is commonly recognized as one of the earliest depictions of the human form by a human civilization that is executed with realism. However, stone sculpture could perhaps go back even further to the late Neolithic period. Evidence exists through objects such as the female steatopygous figure, referring to a female figure with broad hips and thighs that is usually a reference to fertility, which was found on one of the Cycladic Islands and which dates to 4500-4000 BCE.

There are many cultures around the world that use marble as a tool to express their religious beliefs, histories, and their culture. Instead of futile attempts at grasping a singular origin story, perhaps it is easiest to begin with a civilization where marble sculpture was a quintessential element of its cultural heritage—that of the Ancient Greeks.

Marble wasn’t always a fixture of Ancient Greek art, and may have been an art medium highly influenced by the Egyptians. In fact, marble sculptures didn’t really begin appearing in Ancient Greece until after the 6th or 7th century BCE (approximately 699-500 BCE), when Greek city-states, or polis, began blossoming due to economic developments via trade links with other civilizations along the Mediterranean. Citizens of the polis, which were typically urban spaces surrounded by landscape, began accumulating enough funds (via trade, exploitation, military exploits, or all three), in order to commission works of art.

Making a sculpture from marble was no easy, or cheap, feat, which we will explore momentarily. The Ancient Greeks didn’t have the tradition of working with marble, but through sustained contact with other civilizations around the Mediterranean, they looked to a civilization that did—the Egyptians, who had almost two thousand years of working with this medium.

Egyptian Sculpture as a Catalyst for Greek Marble Sculpture

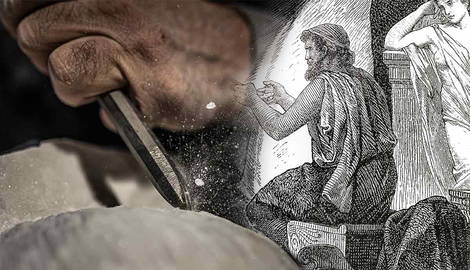

How did Egyptians make sculptures from stone? Through leftover unfinished Ancient Egyptian stone sculptures, scholars were able to identify that the outline of the sculpture would be drawn onto all four sides of the stone, then it would become revealed through a technique that included chiseling away at it with percussive instruments and then smoothing it out with abrasive tools, working from the outside to the inside until the sculpture would slowly take shape. The material of abrasive instruments depended on the stones’ hardness. For softer stones such as limestone, abrasion tools would be made from bronze or copper. For harder stones, abrasion tools would oftentimes be made from the same material as the sculpture, such as granite. Limestone is what used to cover the Great Pyramids of Giza, constructed during the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt (between 2600-2500 BC).

Rather than blending into the sandy Egyptian landscape, under the sun these monoliths would have glistened white. Additionally, a relief painting from the tomb of Rekhmire shows that there was no single artist in Ancient Egypt, but instead, workshops in which multiple people would work on a single sculpture at once. Borrowing from the Egyptians, the Greeks adopted the idea of sculpture workshops in addition to the Egyptian methods of drawing out the sculpture onto all four sides of the marble block and then using percussive and abrasive instruments to chisel away at the design. Due to geologic circumstances, the Greeks required the use of iron for abrasive implements because of the harder, crystalline nature of their marble, as compared to the softer limestones used by Egyptians.

Greek Sculpture in Classical Times

The Greeks, whose civilization began flourishing around the 6th and 7th century BCE, used their newfound wealth to fund arts and culture. The process of creating a marble sculpture began first with an idea—marble would be selected from quarries (which would be in Aphrodisias in southwestern Turkey or in the Cyclades islands of Naxos, Tinos, and Paros) depending on the intended size of the sculpture. Once the proper marble block was selected, it would be transported to a sculpture workshop (located in Aphrodisias, Pompeii, Athenian Agora, Delos, Panatinos, Poteluli), where a team of sculptors and assistants would be present to work on the sculpture. Polishing may have been one of the most important jobs. Marble was referred to as marmos in Ancient Greece, meaning shiny stone, a reference to the visual shine that the material would have after being polished.

In Ancient Roman sculpture workshops, there were people specifically assigned to polishing the sculptures, which would oftentimes take longer than creating the sculpture itself. Much like in Ancient Egypt, the sculpture would become revealed by chiseling away at the design on all four faces of the block.

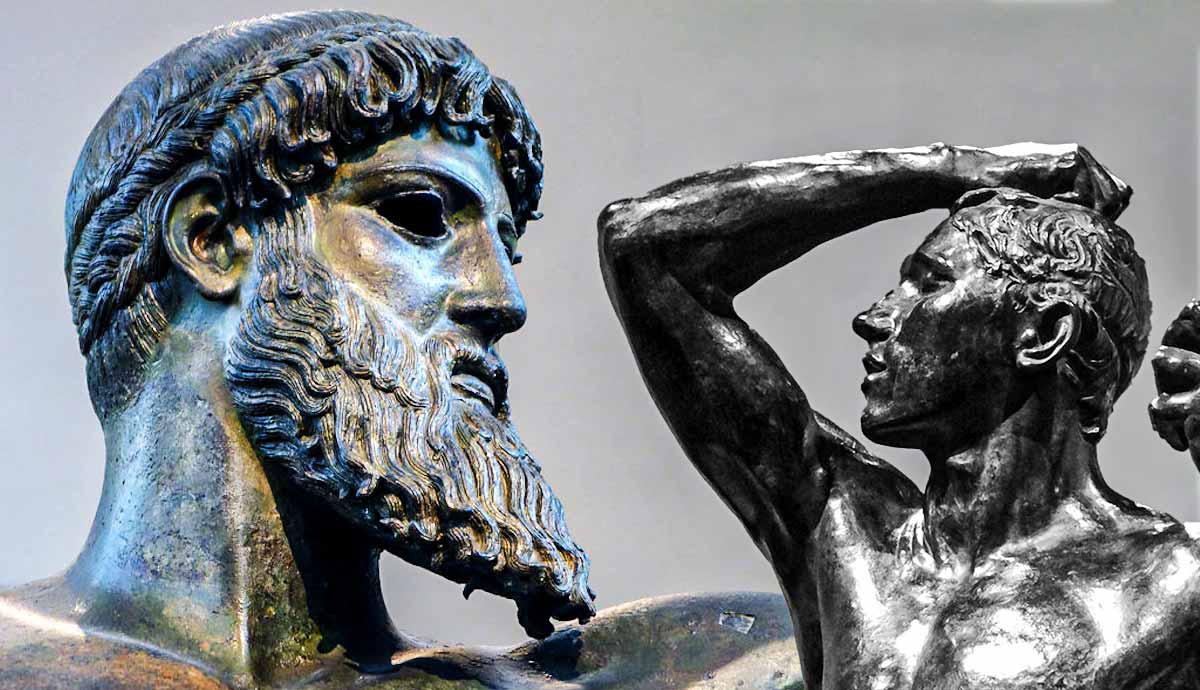

Today, we characterize Classical sculpture by its chalky white color, but in fact, the works were actually painted. Ancient Greeks had a philosophy regarding the importance of variety, or poikilia, which manifested itself through marble sculpture. Sculptures would be chiseled with the intention of making light and dark contrasts. In combination with the textures of the marble, the paint would be applied strategically to further enhance clothing, physical characteristics, or emblems. Detailed ringlets of hair, smooth, sometimes veined skin, and muscular human anatomy beneath polychrome, or multiple, colors would be visible. Take, for example, the Hellenistic sculpture of Laocoön. The snakes would have been painted bright green, while red would have dripped from the puncture created in Laocoon’s side.

The Function of Greek Marble Sculpture in Classical Times

Marble grave markers are where the influence of the Egyptians is most visible in Ancient Greek sculpture. Egyptian sculpture is characterized by figures that are forward-facing with one stiff foot reaching out before them. The hands of these sculptures rest in rigid fists by their sides. Archaic (776 BC to 480 BC) Greek marble sculpture adopted this stylization of the human form in grave markers that were referred to as kouroi for boys or men and kourai for girls and women.

However, kouroi and kourai, although still characterized by stiffness, diverged from Egyptian styles in the way that they were depicted nude and the way their bodies didn’t hug so close to the sides of the sculpture. The one foot stepping forward was the origin of what would become the infamous contrapposto stance, which created realism in the human form through the asymmetrical balance of the hips and legs. As Greek society progressed, kouroi statues were replaced by marble reliefs.

Other marble sculptures produced during the Archaic (776 BC to 480 BC) and Classic periods (479-323 BC) of Ancient Greece were produced for rituals, either publicly or privately. Public temples would house a single sculpture which would be placed in the central room, referred to as a cella and would be an active participant in the rituals and sacrifices taking place in front of the temple altar through their gaze. Typically, temples were designed so that from the point of view of the sculpture, it would have a full view of what was happening outside the temple from its position in the cella. However, this would have been just one function of marble sculpture. They were also used as grave markers, especially during the Archaic period.

Romans Copied Greek Sculptures in Classical Times

Romans copied many, if not most, marble statues made by the Greeks. Why? The Ancient Roman Empire lasted from 625 BC to 476 AD, although it is also seen as ending with the fall of Constantinople (modern Istanbul in Turkey) in 1453. As the Roman Empire was expanding in the 4th century BC (400-301 BC), they were exposed to the landscapes, foods, and cultures of other regions across the Mediterranean. One region that highly impressed them was that of the Greeks. After conquering the Greek city-states around 140 BC, they brought back the fruits of their spoils in the form of looted Greek art, much of which were sculptures.

Greek sculpture became a commodity of such high demand in Ancient Rome that both Greek and Roman sculptors would make plaster casts of Greek statues to replicate them. Additionally, it has been understood that the process of copying bronze statues in marble created a lack of balance, and thus required the use of supports, which is why many Roman statues aren’t free-standing but are usually leaning on a support that has been disguised to blend with the theme or character of the sculpture.

However, Anna Anguissola, in her book Supports in Roman Marble Sculpture: Workshop Practice and Modes of Viewing, argues that both Greeks and Romans used the help of supports in their sculptures, to either make the sculptures structurally sound or to enhance or contribute to the story or person that was being depicted. Anguissola, an Associate Professor of Classical Archaeology and Director of the Plaster Casts and Antiquities Collection at the University of Pisa, also wrote that Ancient Romans would source their marble from the Greek Island of Paros.

Another element characteristic of Roman marble that diverges from the Greeks is their use of realistic portraiture. Ancient Rome was known for creating marble sculpture heads, known as busts, which are some of the earliest examples of portraiture that capture the physical features of the person it was intended to represent. Marble busts were part of a tradition that tied back to funerary practices in which a portrait of the deceased functioned as a connection of the people who were still alive to their ancestry. During the peak of the Roman Empire, the Roman Republic (509 BC and lasted until 27 BC), busts were used to represent lineage and thus legitimacy as a political leader or other high-ranking social position or were awarded for success in military leadership or achievement.

These marble portraits would have also been painted. Although there is not much information available regarding the pigments that were being used, there is evidence that women would have been depicted in lighter skin tones than men. This isn’t completely abnormal, considering this is a stylistic choice that is present throughout the Mediterranean, even in Ancient Egypt. There is much speculation as to why, but it has been argued that women stayed indoors more than men, and thus were less exposed to the sun. However, in Tan Men/Pale Women: Color and Gender in Archaic Greece and Egypt by Mary Ann Eaverly, a Professor of Classics at the University of Florida, the author argues that the two colors functioned as a metaphor for duality that echoes the Chinese philosophy of Yin and Yang: opposition together creates balance.

The Lasting Impact of Marble From the Classic World

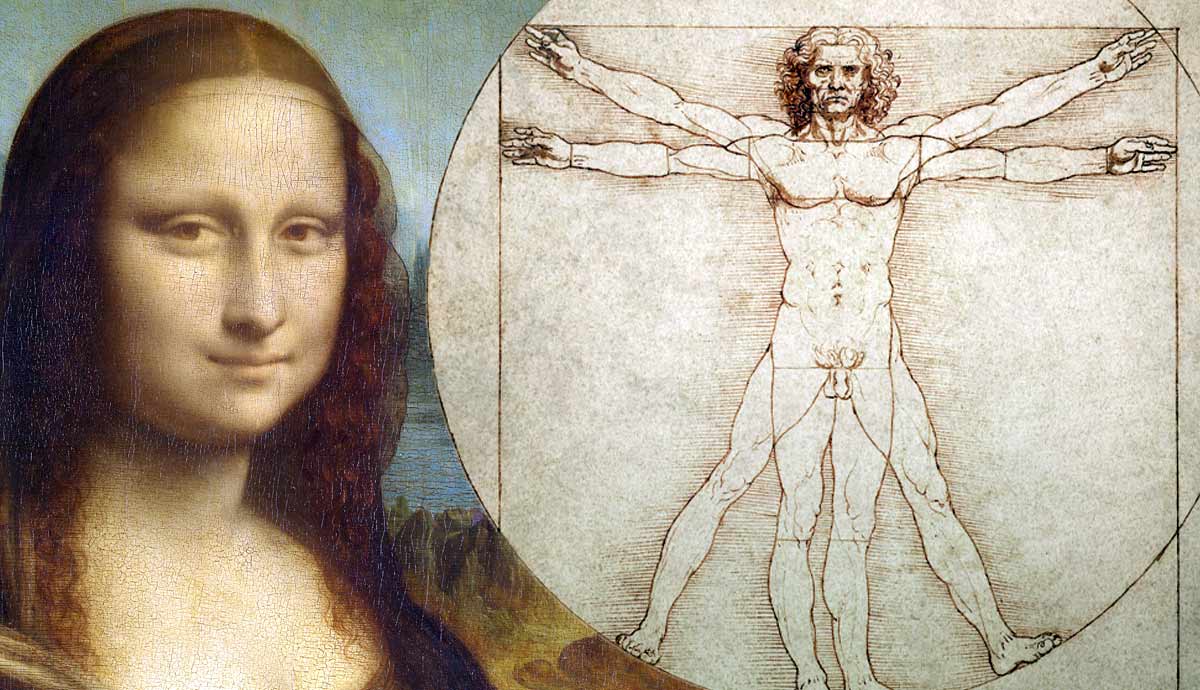

Marble sculptures would have a lasting influence on the periods that came after it, especially during the Renaissance in northern and western Europe. In fact, the philosophies, art, and ideas of the Classical Greek and Roman world were an integral part to the humanists and the Renaissance movement from its beginnings in the 14th century to the 17th century. Renaissance artists looked specifically to Greek and Roman marble sculptures as a source for their renewed philosophy that, among many other things, promoted individualism and realism. For them, these concepts were exemplified in the anatomically accurate, balanced, and visually appealing marble statues of the Greeks and Romans, whose forms and mythologies they would replicate in the execution of their own works of art.

Many Renaissance artists didn’t confine themselves to marble, instead opting to work in the new tradition of oil painting. However, the tradition of working with marble continued and reached a peak with the works of Michelangelo. The 17-foot marble statue of David echoes Greek and Roman statues through its realistic anatomy, and it was made with chiseling tools Michelangelo made himself. After the Renaissance, during the Baroque period, artists such as Antonio Corradini continued this tradition with his ephemeral, ghost-like statues whose thin veils move like wind and echo Ancient Greek works such as the Nike of Samothrace.

Classical sculpture received a second revival during the Neoclassical period, when again artists and philosophers sought influence from Greek and Roman art forms and literature. Rather unfortunately, however, Neoclassicists’ appraisal of Greek and Roman marble statues was also due in part to their white colors, which reinforced ideas of perceived white superiority circulating at the time in Europe (and elsewhere).

Classical marble sculpture still circulates in pop culture through the art form of tattoos. Many people in the 21st century choose to recreate or reference Classical marble sculptures on their bodies. While working in marble is not as common today, the material is still being used by artists such as Jago, an Italian sculptor whose marble sculptures bear many similarities to both Classical and Renaissance sculptures. Both examples represent a continuation of an art form that reaches back to the Classical World.