While the Romans persecuted Christians early in the rise of Christianity, Roman religion was, in fact, very open and adaptable. When the Romans encountered new people and their gods, they often incorporated these foreign deities into their religious practices, either as new gods or as local manifestations of the familiar Roman gods. Some of the foreign gods that gained significant popularity, even in Rome itself, came from Egypt, which was already considered an ancient civilization in the days of the Roman emperors. The Egyptian gods most popular among the Romans were Isis and Serapis, but many other Egyptian gods were often worshiped alongside them in their temples. So, which Egyptian gods were worshiped in Rome?

How Egyptian Gods Arrived in Rome

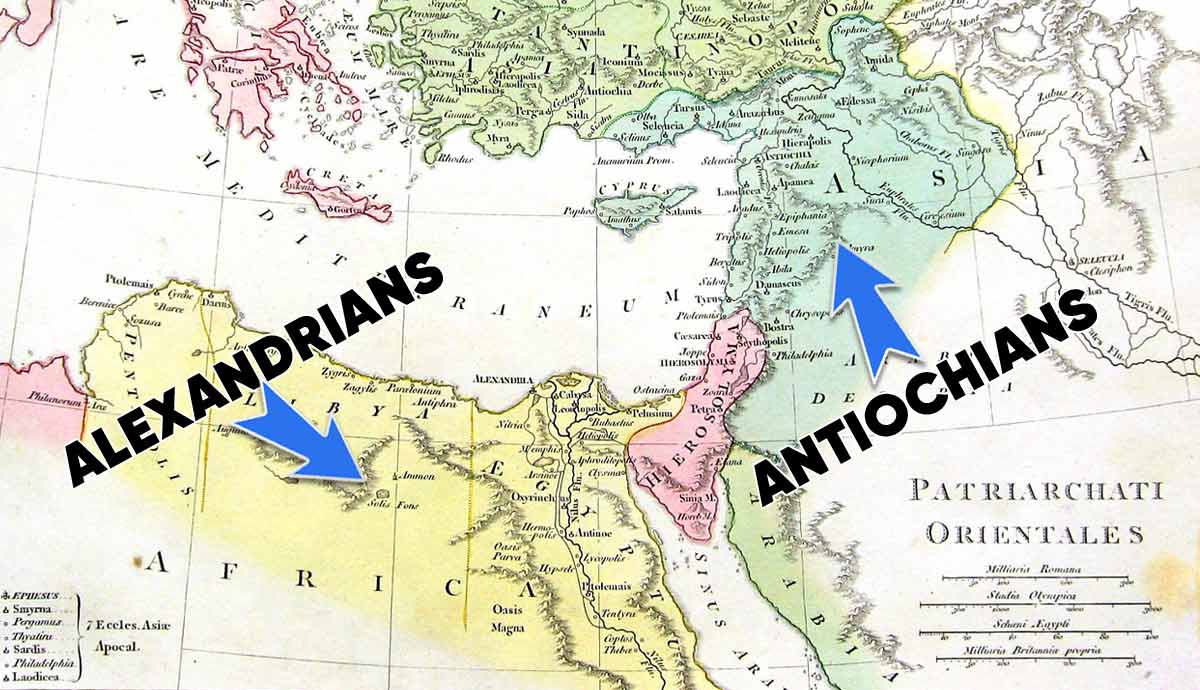

Egyptian gods reached the Italian peninsula early in Italian history, with the first archaeological evidence of Egyptian culture in Italy dating back to the 8th century BCE. Egyptian influence spread through trade, and the first temples and shrines dedicated to Egyptian gods, dating from the 3rd century BCE onwards, were mostly dedicated by wealthy merchant families near trade routes and exchange centers. In Italy alone, excluding Rome, 200 inscriptions related to the cult of Isis have been discovered.

The Egyptian gods soon found their way to Rome, with evidence of shrines and altars set up by private citizens on the Capitoline Hill, in the heart of Rome, from at least the 1st century BCE. These are often described as dedicated to Isis, Rome’s most popular Egyptian deity. However, other Egyptian deities were worshiped alongside her in her temple. The servile classes were well-represented among the worshipers at these new shrines.

In the middle of the 1st century BCE, the Roman Senate tried to exercise some control over these foreign cults that were becoming popular in Rome. The Romans believed strongly that their prosperity relied on the Pax Romanum, which was the favor of the gods, carefully maintained through proper worship. The Senate was concerned with ensuring that new cults did not threaten existing cult practices. Consequently, in 53 BCE, the Senate ordered the destruction of Egyptian temples and shrines, though their orders seem to have been largely ignored. Another story suggests that in 48 BCE when a sacrifice was being conducted to Isis on the Capitol, a swarm of bees settled near the sanctuary of Hercules. This was considered a bad omen, and the sacred enclosure of the Egyptian gods was destroyed.

Egyptian cults were restored briefly by the Second Triumvirate. But when Octavian (Augustus) and Mark Antony found themselves in conflict, Octavian banned them from within the pomerium. The pomerium marked Rome’s sacred border, though the city spilled beyond its limits. This marked Egyptian cults as “non-Roman.”

Nevertheless, Egyptian deities had a way of bouncing back. We hear of a temple of Isis in Rome under Tiberius. The young Domitian hid among the worshipers of Isis in the Capitol when Vitellius’s forces took the city. Later, as emperor, Domitian restored the temple of Isis which was damaged during the fire of 80 CE. Hadrian enlarged the temple, and inscriptions show further expansion under Septimus Severus and Caracalla. In the end, worship of the Egyptian gods in Rome would only be stamped out by Christianity, just like worship of the traditional Roman gods.

Isis

Isis is the Egyptian goddess most often mentioned in Roman sources. She seems to have been the most popular Egyptian god among the Romans, and a kind of “head” of the Egyptian pantheon in Rome. Most temples were called “Iseum,” suggesting they were primarily dedicated to Isis, but other Egyptian gods were worshiped alongside her.

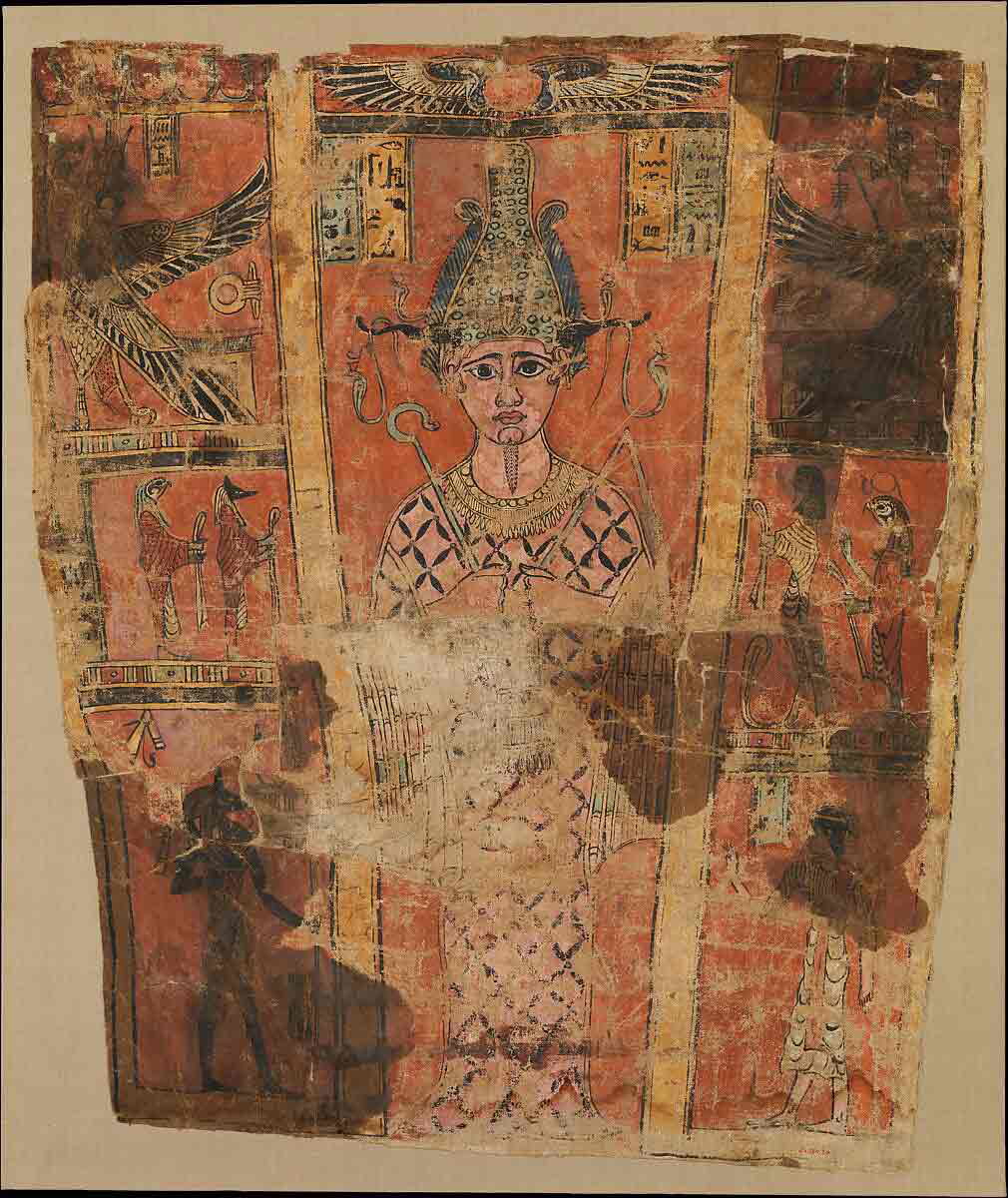

While Isis started as a relatively obscure Egyptian deity, by Roman times she was the most important goddess in Egypt. Married to her brother-husband Osiris, it was her powerful magic that brought him back from the dead and created the afterlife for him and all others. She also impregnated herself with her dead husband’s seed to give birth to Horus, the divine counterpart of the pharaoh, making her the wife and mother of kings. She was considered the divine feminine, goddess of magic, and personal protection goddess.

Isis was attractive to the Romans for several reasons. First, women and members of the servile class, excluded or given secondary positions in most Roman cults, were able to play leading roles in her worship. Second, she was linked with mystery and magic, and mystery cults that involved special initiation, such as Mithraism, became very popular in Rome between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. The other thing these cults had in common was that they encouraged personal devotion, rather than simple ritualistic duty. This was another element that was becoming popular, and it was also seen in the rise of Christianity.

Osiris

Osiris was popular among the Romans, alongside his wife. For the ancient Egyptians, Osiris was the first king of Egypt who was killed by his brother Seth out of jealousy and became ruler of the underworld. He was also linked with fertility and the annual flooding of the Nile and was sometimes associated with the sun god Ra.

The Romans seem to have been principally interested in Osiris in his capacity as god of the Underworld, suggesting that they embraced the Egyptian idea of an idyllic life after death that could be accessed through Osiris. The oldest inscriptions referencing the god are funerary inscriptions in which the dedicator asks that Osiris give the deceased “fresh water,” which was necessary for them to pass into the Underworld. Interestingly, the surviving inscriptions were mostly dedicated by ex-slaves and written in Greek.

Ovid, who describes the practices of his household cult on several occasions, mentions a prayer he made to several Egyptian gods during the pregnancy and labor of his wife Corinna. As well as Osiris, he mentions Isis, Anubis, and Apis.

“Isis, thou who dost inhabit Parætonium, and the genial fields of Canopus, and Memphis, and palm-bearing Pharos, and where the rapid Nile, discharged from its vast bed, rushes through its seven channels into the ocean waves; by thy ‘sistra’ do I entreat thee; by the faces, too, of revered Anubis; and then may the benignant Osiris ever love thy rites, and may the sluggish serpent ever wreath around thy altars, and may the horned Apis walk in the procession as thy attendant; turn hither thy features, and in one have mercy upon two; for to my mistress wilt thou be giving life, she to me… ” (Ovid, Amores, 2.13).

Serapis

Even more popular than Osiris was Serapis, and as well as “Iseum,” we hear of “Serapeum” in the Roman world. But Serapis was a god closely linked to Osiris. When the Ptolemies took over Egypt in the 4th century BCE, they wanted to focus religion on a deity that would be acceptable to both Greeks and Egyptians. They adopted Serapis, who combined the Underworld god Osiris with the Apis Bull, which was sacrificed and reborn each year to maintain the proper lifecycle of the universe and Ma’at. The new Ptolemaic Serapis began to usurp Osiris as the consort of Isis and father of Horus, including in Roman worship of the Egyptian gods.

As well as being worshiped alongside Isis as the masculine element in Egyptian mystery cults, and syncretized with Dionysus, Serapis became a patron of the imperial family under the Flavians. This began with Vespasian, who made his bid for imperial power in 69 CE from the east, primarily in Judea and Egypt. While in Egypt, he claimed to receive several omens that heralded his future power, including having a vision in the temple of Serapis. After this, he became a vassal of the god and performed two acts of healing. He spat in the eyes of a blind man so that he regained his sight and stood on the hand of a lame man to restore proper movement (Suetonius, Vespasian 7). When he returned to Rome, Serapis continued to be a patron of the Flavians and a symbol of their divine right to rule, and so was included on the imperial coinage.

It is entirely possible that the story of Domitian seeking refuge among the followers of Isis during his father’s bid for power was a later invention, designed to make Isis his patron, just as Serapis was his father’s.

Anubis

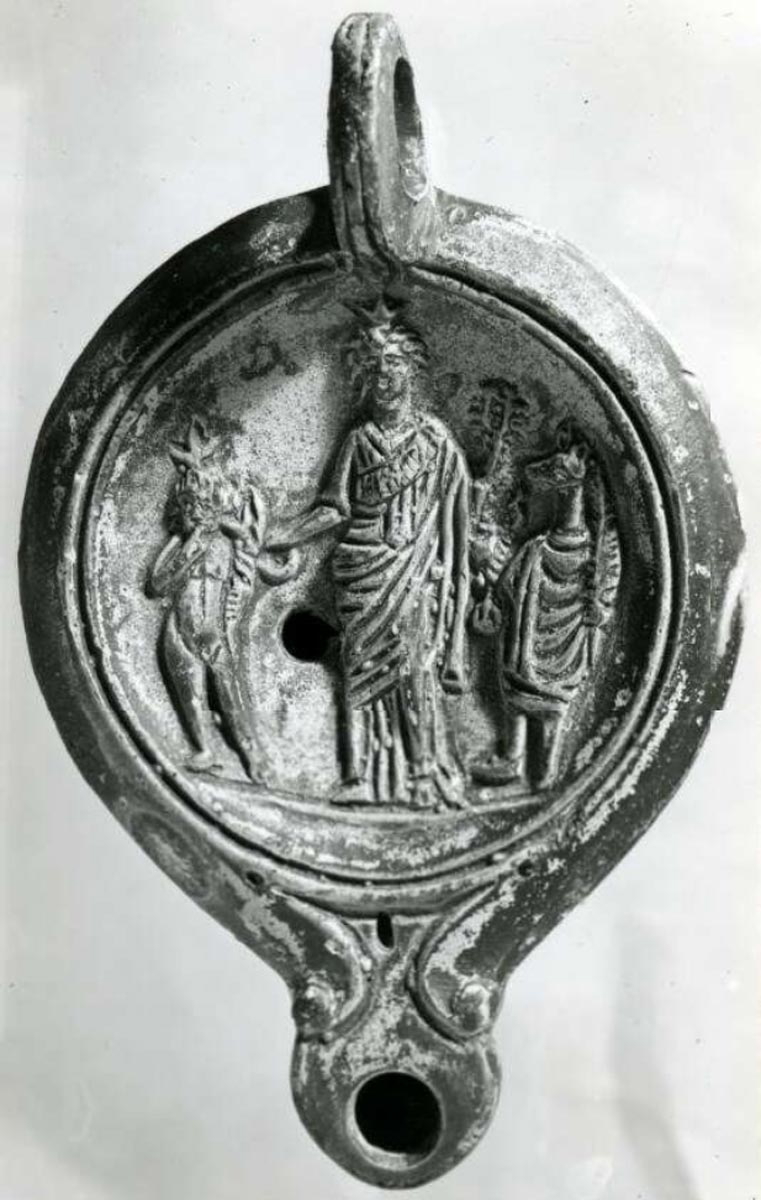

Anubis was another Egyptian god worshiped alongside Isis, Osiris, and Serapis. He was another god of the dead. The jackal god was considered the guardian of graves and was later included in the Osiris myth as helping Isis develop the process of embalming that gave Osiris his second life. The Egyptian jackal-headed god then became one of the principal gods that guided the dead on their journey to the Underworld. He seems mainly to have been embraced by the Romans in this role, often associated with Hermes/Mercury, a messenger god who also guided the dead.

Anubis was already transported into the Greek world alongside Isis in the 2nd century BCE, where votive inscriptions show that he was worshiped at the temple of Isis at Delos as her adjunct. The same seems to be true in Rome, where some priests of Isis wore jackal masks. Josephus (Antiquities 18.3.4) tells the story of a Roman matron seduced by a priest disguised as Anubis. Images of men in Anubis masks are also found throughout the Roman world.

Horus

Horus was the son of Isis and Osiris who avenged his father Osiris and took up his mantle as king of Egypt. The Egyptian Pharaoh was considered the mortal incarnation of Horus, and thus he was one of the most important gods in ancient Egypt, but the Pharaoh was not a particularly important figure to the Romans. The Romans did invoke Horus as a leader figure, with surviving images of him in Roman military dress. But the Romans focused more on Horus and his connection to the sun as a helper of Ra, and also as the child in the divine triad that was made up of Isis, Osiris/Serapis, and Horus, often called Harpocrates in this context.

In Egyptian art, Harpocrates, the child version of Horus, often appeared with his finger at his lips. Apparently, the Greeks mistook this for a symbol of silence and secrecy, and this became an aspect of the god, which was incorporated into the Egyptian mystery cult in the Greco-Roman world. He was also sometimes associated by the Romans with Hercules, since he avenged his father, and Hercules assisted his father Zeus during the Gigantomachy.

Other Deities

Other Egyptian deities popped up around the Roman world, but it is unclear how extensive and organized their worship was. Thoth seems to have been popular as a god of wisdom, and he became particularly popular among early Christians, syncretized with Hermes, and considered the source of the Hermetica, 42 sacred books containing all the world’s knowledge.

We also know that when Vespasian’s son Titus was in Egypt, he participated in a ceremony related to the Apis bull wearing a diadem. He later minted coins with a bull on the reverse. Perhaps he chose the Apis bull as his Egyptian patron like his father did with Serapis and his brother with Isis.

Amun was very popular at different stages throughout Egyptian history and during the New Kingdom, he was considered the god who created himself and the king of the gods. In Greece, he became syncretized with Zeus and Zeus-Amun, and in Rome, he became Jupiter-Amun, often depicted with the ram horns associated with Amun. Through this kind of syncretization, many Egyptian gods found their way into mainstream worship in the Roman world.

Selected References

Gasparini, V. (2008) “The Introduction of the Worship of Isis in Rome,” Archaeologie Online.

Pubblico, M.D. (2023) “The Emergence of the Osiris Cult in the Italian Peninsula and its Main Features: A Reassessment,” Religions 14.4, 484ff.