This article explores Scottish philosopher David Hume’s ‘bundle theory’ of the self. We will first tackle the concept of the ‘self’, how it is defined and how we can distinguish it from other related concepts. There is a particular difficulty in posing questions about the self without assuming its existence. We will also take a look at David Hume’s bundle theory in detail and analyze its radical negation of the self as contrasted with the way many philosophers ordinarily conceptualize selfhood. Near the end, we will also discuss the relationship between Hume’s theory of selfhood and his empiricism, including the possibility of an exception in the subordination of interiority to the outside world which Hume’s scheme seems to imply.

A Precursor to David Hume’s Bundle Theory: What Even Is a Theory of Self?

Before examining Hume’s theory of self in detail, it would be helpful to say something about what a theory of self might be. This is a difficult question to answer directly. One is tempted to reply that the ‘self’ is what we are most fundamentally. But we must take care to ask this question without indirectly assuming that there is such a thing as what we fundamentally are, and that there are questions of depth and shallowness in the context of ourselves.

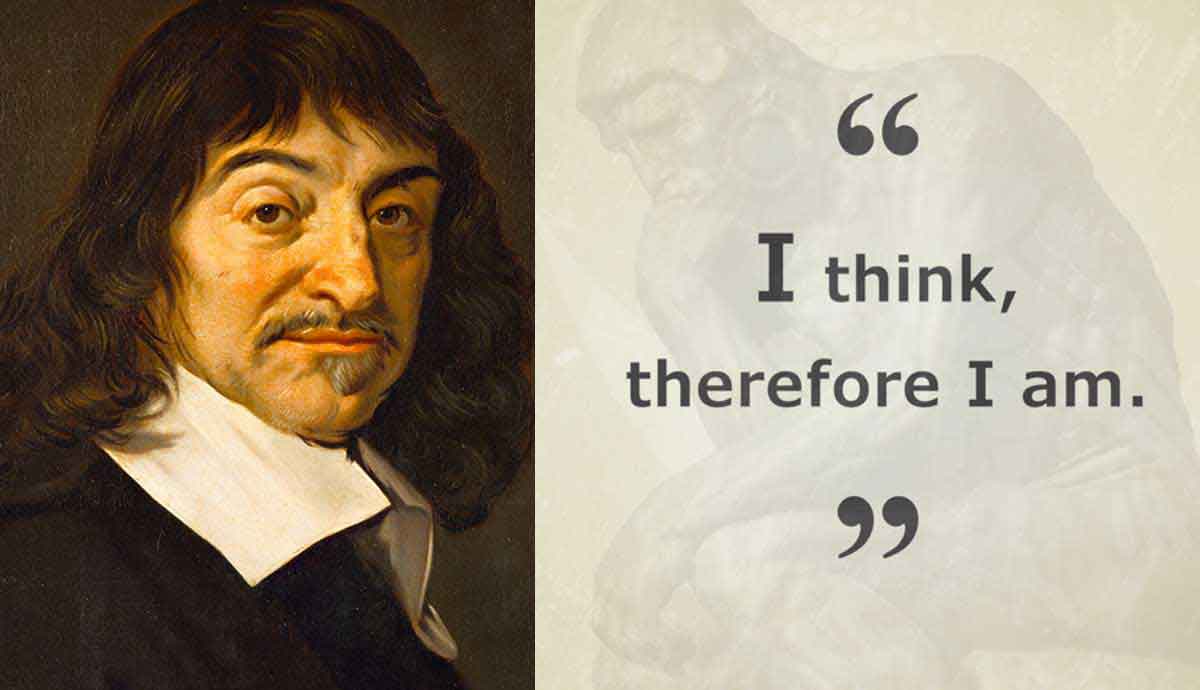

To understand where I am going here, we can draw an analogy to this kind of confusion in the famous Cartesian ‘cogito’ argument. When Descartes holds that, because I think, therefore I am (cogito ergo sum), he makes this move not from a certainty about the existence of the ‘I’, but only the existence of thought itself. He assumes the existence of a subject, because this is what we tend to do in ordinary life and ordinary speech. However, as soon as we start to ask questions like ‘what is the self’, ‘under what conditions can the self change’, or ‘is the self a simple thing or a complex thing’ that appearance of obviousness disappears.

The Self, the Mind, and Persons

When we ask difficult questions about ourselves, we may be forced to choose between alternatives which are, in different contexts, similarly unappealing and difficult to accept. The most fundamental question a theory of self must answer is whether there is such a thing as a self: whether we are one thing fundamentally.

If the first problem we might run into when attempting to theorize the self is the assumption that there is such a thing as a ‘self’ in the first place, the second is confusing our concept of self with other, adjacent concepts. The concept of self interacts in various ways with two further concepts in particular.

Firstly, there is the concept of a person. We might think of a ‘person’, in a philosophical context, as the answer to the question ‘what are we most fundamentally in an ethical context’. Second, there is the concept of the mind, which admits no straightforward definition but those we give to it ordinarily; it is where consciousness happens, it is what happens ‘in our heads’, it is what we use to think. None of these definitions are satisfactory on their own; perhaps a more satisfactory definition exists, or perhaps no one definition will do.

The Human Conception of Self

Hume’s conception of the self has proven extremely influential, and can be characterized using the following passage: according to Hume, the mind is

“nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in a perpetual flux and movement […] The mind is a kind of theatre, where several perceptions successively make their appearance; pass, repass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of postures and situations.”

What Hume is getting at here is that how we ordinarily conceive of our minds when we are called upon to describe what goes on in them is quite different from how we actually experience them. Hume’s conception of mind implies a conception of the self which is either thin or non-existent. Sometimes this is called a ‘Reductionist’ theory of ourselves; that we are not, fundamentally, anything more than a flux or (at best) a system of various different things. We are no one thing, fundamentally.

The Ordinary View of the Self

We tend to describe ourselves in ways which emphasize overarching continuity and stability. Whatever change there may be in our minds is subordinate to fundamental sameness, both at any one moment and over time. Certainly, many, many philosophers still hold that this or something like this is true. If we take this to be a general assumption about ourselves, then we should divide the views which broadly adhere to it into two kinds of variation.

On the one hand, we might think of this assumption as implying the existence of something like a soul; some part of ourselves which is fundamentally unchanging, no matter how much what actually goes on in our mind might change. On the other hand, we might argue that there are some features of our mental life which are inevitably continuous with one another. This article doesn’t go further in exploring these alternatives, but that is an approximate summary of what Hume’s view sets itself in opposition to.

Relations Among Parts

There are two features of the ‘bundle theory’ which deserve independent consideration. First, there is the relation among parts: a ‘bundle’ implies a collection of unrelated things, or at least things which are not intrinsically related. There are two ways we can interpret this.

One is to say that our minds consist of wholly independent elements. This seems quite implausible; even without a thoroughgoing theory of mind, the idea that any part of our mind is wholly independent from any other seems difficult to accept. On the face of it, it is more plausible to interpret Hume as denying the intrinsic integration of our minds.

Even if the various parts of our mind can and do operate systematically or at least in coordination with one another, that does not mean that in principle one part could not be separated from another. We could imagine a complicated machine, in which each cog does fit together to form a coherent system, but the machine could be taken apart, and any one cog could also be put to various other purposes.

Explaining Time and Change

The second feature of the bundle theory worth considering independently is the conception of time and change contained within it. Hume conceives of our mind as a rapid succession of perceptions (or, the ideas which are formed from perception). Much as our perceptions interact with one another, for Hume they are in succession, and there is nothing in Hume’s theory to suggest that there is any genuine continuity here. Rather, he emphasizes the speed at which perceptions pass, the suggestion here being that we are misled by that speed into believing thought to be a single thing with many parts.

One of the most significant consequences of this view is ethical. We normally think of ourselves, from a moral perspective, as a unified thing. If, for instance, I harm someone at one point in time, I might be liable for punishment at a later point. Hume’s doctrine throws ethical judgments of this kind into serious uncertainty.

If one wants to criticize Hume’s conception of the self – which amounts to a denial of any fundamental core self whatsoever – then it is worth asking: what does it rely upon? First, there is a claim that our minds are constituted by perceptions. Hume’s view is that simple ideas are effectively the imprint of simple perceptions: “All our simple ideas in their first appearance are deriv’d from simple impressions, which are correspondent to them, and which they exactly represent”. Moreover, all of our complex ideas are the aggregation of simple ones according to what he calls ‘habits of mind’ – the ordinary patterns of thought. Hume’s conception of mind is therefore wholly reliant on an empiricist view of the world; one in which the ultimate currency of thought is perception, and thought is a product of interactions with things outside of thought. Interiority is a product of the external world.

What About the Priority of the External World?

Yet it is here that some care must be taken to emphasize that Humean empiricism carries with it a strong implication of the uncertainty of any attempt to make firm judgments, particularly when tracing the relationship between ourselves and the external world.

Although Hume claims at various points simple ideas exist in a one to one relationship with simple perceptions, he also leaves it as something of an open question:

“whether ‘tis possible for him, from his own imagination, to … raise up to himself the idea of that particular shade, tho’ it had never been convey’d to him by his senses? I believe there are few but will be of opinion that he can; and this may serve as a proof, that the simple ideas are not always deriv’d from the correspondent impressions; tho’ the instance is so particular and singular, that ‘tis scarce worth our observing, and does not merit that for it alone we shou’d alter our general maxim”.

Here, Hume strikes a cautious note; suggesting that in certain, exceptional cases, we can think of things which are not simply the accumulation of perceptions. The question then is whether Hume is attempting to gesture towards some part of our minds which is less dependent upon external reality, from which we might derive a more fundamental, more indelible concept of self.