Tutankhamun is, for many, Egypt’s most famous Pharaoh. Quite a few Pharaohs would take offence, starting with the pyramid builders, the mighty Thutmose III or Amenhotep III. However, it is Ramses II who would probably contest this statement the most. Indeed, during his reign (the second longest in Egyptian history), Ramses II sought to restore Egypt’s power and launched extensive building projects. Here is the story of what makes Ramses II ‘Great.’

Ramses II Inherited Egypt From A Great Pharaoh

Until his tomb discovery in 1922, no one outside of Egyptologist circles had ever heard of Tutankhamun. As a consequence of the turmoil caused by his father Akhenaten’s religious reforms, images of Akhenaten, his wife Nefertiti, and son Tutankhamun were smashed and their names erased. After a short reign, Tutankhamun, buried in a small tomb, became all but a minor footnote in Egypt’s long history.

After the reigns of Ay and Horemheb, Ramses I, Horemheb’s vizier, ascended the throne in 1292 BCE. While Ramses was of advanced age, he had a son and grandson, lessening the risk of succession chaos. The founder of the 19th Egyptian dynasty, Ramses I restored stability in Egypt. His son, Seti I, and grandson, Ramses II, revived its glory.

Ramses I’s reign only lasted two years. Seti’s would last nearly 15 years. For military matters, Seti lost no time in legitimating his son’s claim to the throne: Ramses was named commander-in-chief at age ten. The young commander later witnessed his father recapture a strategically important town, Kadesh.

Seti’s reign saw a Renaissance-like period in Egypt, with attempts to emulate the great conqueror Thutmose III and the great builder Amenhotep III. Indeed, Seti restored classicism in art, largely contributing to two of Egypt’s marvels, Abydos’ temple and the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak.

However, the reign of his son overshadowed the importance of Seti’s reign. While Seti succeeded at rivaling the achievements of past pharaohs, Ramses II went on to surpass all before him.

He Had The Longest Reign Of Ancient Egypt

Ramses became pharaoh in his early 20s and went on to rule for a record of nearly 67 years. Only Pepi II had previously governed that long, around 63 years, at a time of decline.

Ramses II’s reign was a display of might that saw Egypt trying to gain control of Asia. Seti had defeated several princes in Palestine and southern Syria. His gains over the Hittites (based in Anatolia) were only temporary. While he managed to retake the city of Kadesh, he then conceded it back.

Regaining Kadesh became Ramses’ defining military achievement. To celebrate his victory at the Battle of Kadesh (1275 BCE), he had scenes of the clash inscribed on the walls of several temples, including those of his Ramesseum (more on that later).

Writing history in stone is indeed the best way to secure one’s legacy. However, the Hittite King Muwatalli II also claimed victory. Today, scholars believe the battle likely ended in a stalemate. Fifteen years later, the Hittite king, Muwatalli II’s successor, and Ramses II returned to Kadesh to conclude a peace treaty, the first known example of a nonaggression pact in history.

Peace brought stability and prosperity, allowing Ramses to become the most prolific builder of ancient Egypt.

Ramses II Built Monuments All Over Egypt

Ramses started his building efforts while still a prince, and as soon as he became pharaoh worked on creating an eternal heritage. The list of architectural works commissioned by Ramses II includes:

- Founded a new capital city, Pi-Ramesses, celebrated for its beauteous balconies and dazzling halls adorned with lapis lazuli and turquoise.

- Expanded the temples of Memphis, the former royal capital.

- Completed Seti I’s temple at Abydos and added a grand temple of his own.

- Built the largest individual tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

- Constructed the largest royal burial chamber of ancient Egypt for his sons.

- Created eight tombs for the women in his life, including his mother Tuy and beloved wife Nefertari.

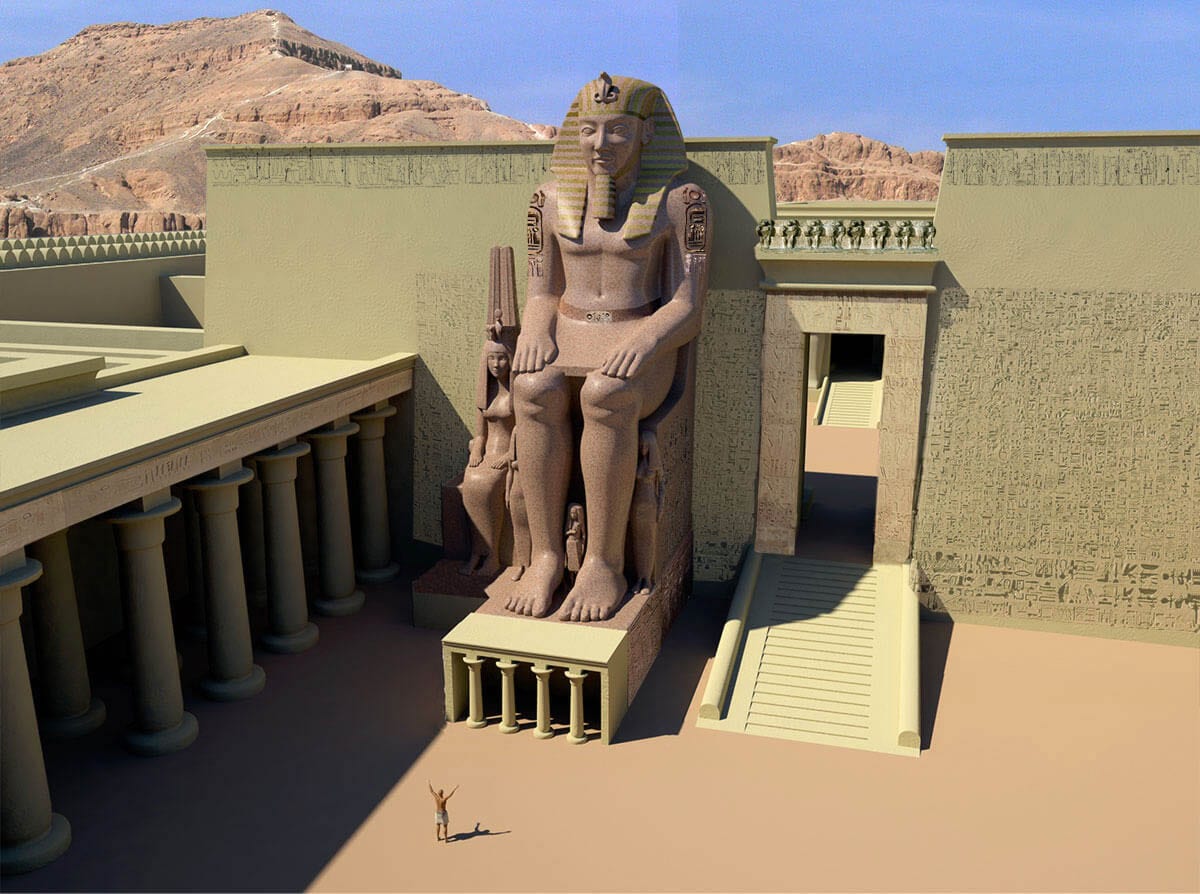

- Commissioned the Ramesseum, one of the largest and most impressive temples in Egypt.

- Added monumental works to the great temples of Luxor and Karnak.

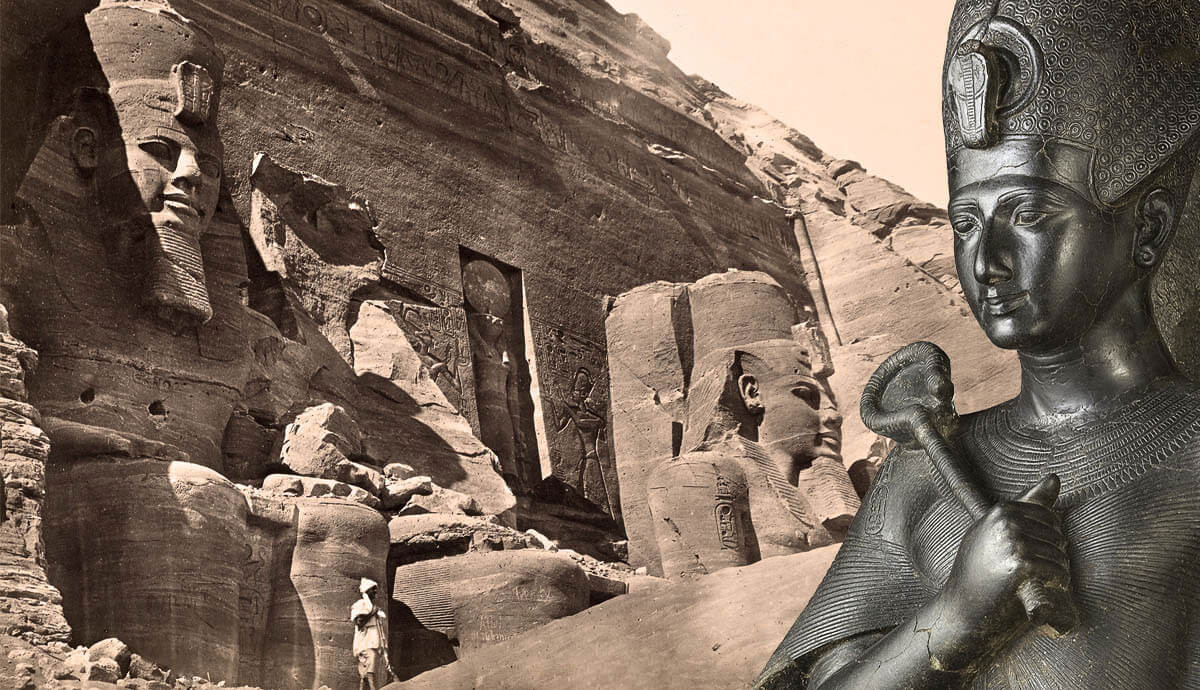

- Erected seven temples in Nubia, crowned by the monumental Abu Simbel.

- Produced over 350 statues, including nearly 50 colossal figures up to 66 feet high, seated.

While previous pharaohs had built impressive pyramids and temples, Ramses turned Egypt into an immense building site, from the Mediterranean Sea all the way to Nubia.

To increase the number of statues of himself, Ramses even employed the typically Egyptian method used to appease impatient rulers: take an existing temple or statue, chisel out the name of the pharaoh who built it, and replace it with one’s own.

Ramses II Was A Living God

In ancient Egypt, pharaohs were considered successors of the god Horus. Most were also sons of the sun god Ra. They were called netjer nefer. Netjer means god, and nefer means perfect, signifying that the pharaoh was a ‘perfect god.’

The association with the gods gave the pharaohs’ function a divine nature. The pharaoh as a person, however, was human. Still, a person who was one step away from becoming a god in the afterlife.

Ramses, however, was more than a ‘perfect god.’ Deep inside Abu Simbel’s temple are statues sitting shoulder to shoulder depicting four gods: Ptah, Amun-Ra, Ramses, and Ra-Horakhty. This suggested that Ramses stood among the gods as an equal, not a lesser god. Reliefs show Ramses II, the man, making offerings to Ramses II, the god.

Some of his giant statues were even subject to a popular cult. A stele depicts a man making an offering to Ramses’ statue, “the great god who hears the petitions of mankind.” The statue was worshiped and received gifts, like those of a proper god.

Ramses II’s Tomb Was The Biggest Of The King’s Valley

Ramses built for himself the largest individual tomb of the Valley of the Kings. For his sons, a royal tomb large enough for more than 120 princes. Both tombs were, unfortunately, badly damaged by the rare but devastating torrential rains.

Eight times larger than Tutankhamun’s tomb, which contained 5,000 items, Ramses’ tomb had a burial room named ‘House of Gold.’ Since only a few reliefs, fragments, and objects have survived thieves and floods, one can only imagine the treasures it would have contained.

The tomb of his Queen, Nefertari, offers an idea of what it might have looked like in its prime. Her burial chamber is one of the finest examples of ancient Egyptian art.

Another monument secured Ramses’ eternal life, the Ramesseum. Also known as the Mansion of Millions of Years, in his lifetime, it was a memorial to the cult of divine Ramses.

The Ramesseum was an economic powerhouse employing thousands. Within the complex, there was a palace, a treasure store filled with “silver, gold, royal linen, every real costly stone”, and fine wines, and a school where scribes learned to write, read classical literature, and paint and sculpt statues.

After His Death, Many Pharaohs Tried To Emulate Him

Ramses was so prestigious that nine pharaohs in succession, from Ramses III to Ramses XI, took his name. Ramses III is the only one whose achievements might come close to those of Ramses II, visible today with an impressive Million Years mansion near the Ramesseum. However, his reign ended abjectly when he was assassinated after a palace power struggle.

The last Ramses left royal power so weakened that Egypt entered another era of division and chaos. Pharaohs buried in the King’s Valley were stripped of all their riches to protect them from thieves.

A new dynasty ruled over half of Egypt. To build their capital, Tanis, the new kings took nearly every stone and statue of Pe-Ramses and moved them 12 miles away. Ramses II’s legacy, however, endured.

Inside the tomb of Psusennes I (1047-1001 BCE), among the gold and silver treasure, was a modest item, a bronze brazier inscribed with Ramses’ name. The former pharaoh’s name could have easily been replaced with Psusennes.’ However, choosing to be buried with an object that had belonged to Ramses II meant hoping to bask in his glory.

Psusennes even called himself ‘Ramses-Psusennes.’ Almost one thousand years after he died, priests had a stele carved, falsely pretending to be associated with the great Pharaoh.

Ramses II Endured 1,400 Years Of Oblivion

Over time, the history of Egypt became exotic folklore. Sand-covered pyramids and temples were often used as stone quarries. People ate mummies as medicine. However, during this long silence, one pharaoh’s name was not forgotten.

Although the Pharaoh in Exodus is nameless, the Old Testament mentions a “land of Ramesses” and a city called “Ramesses.” Some ancient Greek and Roman historians also mentioned a Rhamsesis, Rhamses, Rampses, or Ramesses.

The Greek historian Diodorus described “a monument of the king known as Ozymandias,” and colossal statues. One of them was “the largest of any in Egypt.” Its inscription read: “King of Kings am I, Ozymandias. If anyone would know how great I am and where I lie, let him surpass one of my works.”

The statue became the inspiration for Shelley’s Ozymandias. Without realizing it, the poet was writing about Ramses II. Ozymandias is the Greek adaptation of an Egyptian name, Usermaatra, taken by Ramses II when he became pharaoh.

Greek Pharaohs had steles carved with Greek texts and their Egyptian translation. One such bilingual text had been found: the Rosetta Stone. The great minds of the time spent twenty years trying to decipher hieroglyphs.

The First Hieroglyphic Name Read By Champollion Was ‘Ramses’

In 1799, an unassuming black stone was unearthed in Egypt: the Rosetta Stone. The great minds of the time spent twenty years trying to decipher hieroglyphs. One of those scholars was Champollion. In 1822, he was finally able to translate the hieroglyphs.

While scholars had already deciphered non-Egyptian names, like Alexander, Ptolemy, or Cleopatra, in the section of the stone written using hieroglyphs, reading proper Egyptian names remained impossible.

Then, Champollion, convinced that ancient Egyptian gave rise to the Coptic language, written in the Greek alphabet and still spoken in the Coptic Christian Church, had a decisive breakthrough.

Using a recently discovered inscription at Abu Simbel, a religious site built by Ramses II, he tried to decipher a group of four symbols, one of which appeared twice at the end.

Believing hieroglyphs could be read either as pictures, as symbols for objects, or as symbols for sounds, he correctly identified the two repeated symbols as an “s.” He then guessed the first hieroglyph represented the sun, Ra. Thus, the name written the sequence “ra-?-s-s” could only be one: Ramses.

Realizing what he had done, Champollion fainted of emotion. After 1,400 years of silence, the first ancient Egyptian word read aloud was Ramses.

He still towers over Egypt, with almost 50 colossal statues. One of Ramses’ obelisks greets visitors stepping out of Cairo’s airport. His effigy appears on banknotes, and streets are named after him.