This article provides an overview of Aristotle’s Poetics, one of the earliest and most influential philosophical treatises on poetry. We will delve into the significance of this work and the profound self-awareness it displays regarding artistic creation. Furthermore, we will explore the poetic landscape that Aristotle was acquainted with during his time. Our exploration will then delve deeper into key concepts analyzed by Aristotle, including mimesis, plot development, and the notion of “fitting size.” Lastly, we will examine Aristotle’s distinction between tragedy and comedy, as well as his insightful account of the pleasure derived from tragedy.

Aristotle’s Poetics & The Importance of Ancient Greek Poetry

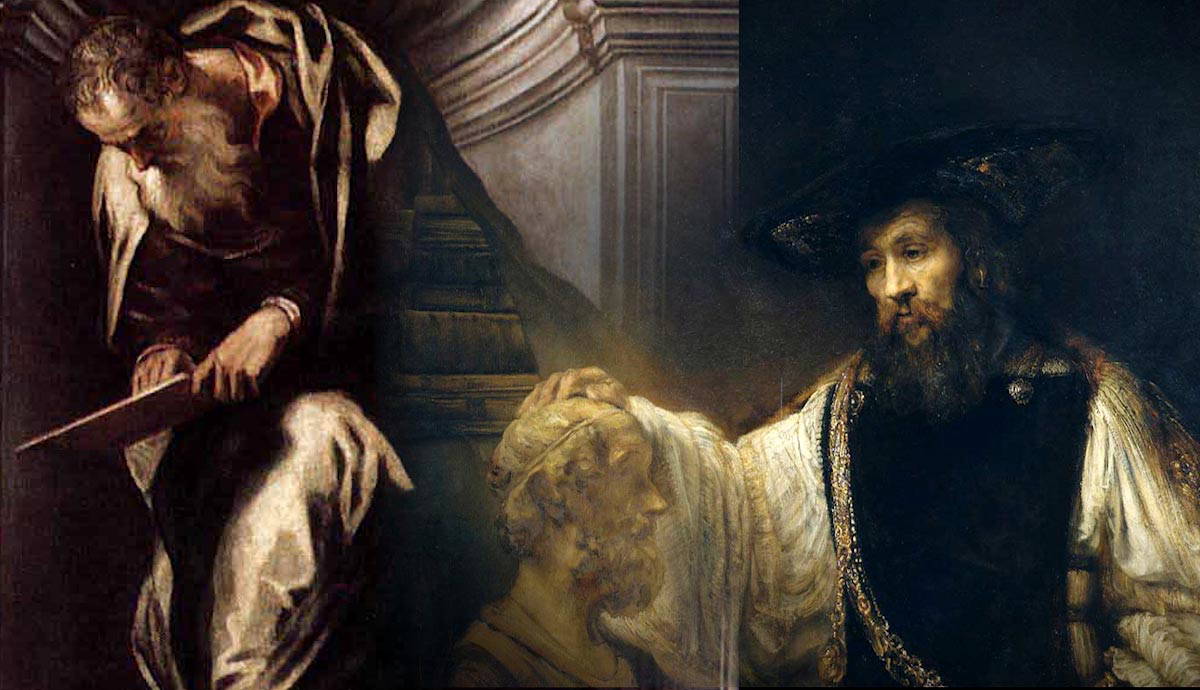

One of Aristotle’s notable works is his Poetics, which holds a significant place among the treatments of poetry in Greek philosophy. While it is not the only or earliest work on the subject, its extensive and influential nature has led to the continued use of the term “poetics” to refer to the study of poetry. The exploration of poetry within the realm of philosophy in ancient Greece is particularly fascinating because it represents one of the earliest attempts to consciously analyze literary works.

Moreover, this philosophical engagement becomes even more intriguing considering the abundance of poets and playwrights in the Greek world, whose works, including dramatic verses, continue to be widely read today. Since Greek drama was written in verse, it can be treated as poetry for our purposes. Before delving into Aristotle’s theory of poetry, it is essential to gain a general understanding of the state of ancient Greek poetry, its themes, and its variations.

Epic poetry likely emerged as the first form of poetry in Greece. Among its most renowned examples are the Homeric epics—the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey“—traditionally attributed to the poet Homer. These epic poems recount heroic tales of the Trojan War and the adventures of Odysseus, respectively. Another significant form of expression in Ancient Greece was lyric poetry. While epics often delved into events, actions, and the exploits of gods and heroes, lyric poetry explored personal emotions, experiences, and more mundane reflections.

Varieties of Poetry in Ancient Greece

Among the lyric poets, some of the most notable figures include Sappho, renowned for her passionate love poetry, and Pindar, who composed choral odes to commemorate athletic victories and religious events.

Greek tragedy emerged later than these two earlier forms, in the 5th century BC, and it primarily took the form of theatrical performances. Aeschylus, credited with being the first to introduce multiple actors and the chorus, is considered a pioneer of the Greek theatrical tradition. Other significant tragedians, including Sophocles and Euripides, explored themes of fate, morality, and the human condition as such. In addition to tragedy, Ancient Greek drama encompassed comedy, too. Comic poets like Aristophanes employed satire and humor, often delivering veiled (or not-so-veiled) critiques of society, politics, and cultural norms.

Lastly, it is important to note that we know there was vastly more poetry and drama than what has been passed down to us, both from writers whose work we have access to, but also from the many writers from whom almost nothing has survived. Many writers and their works have been lost to history. This perspective is crucial when considering Aristotle’s work, as he may be describing trends in poetry that are challenging to discern from the sliver of Greek literature that has survived, but align with the broader corpus that Aristotle would have been familiar with.

The Poetics as a Guide to Good Poetry

Aristotle’s Poetics serves a dual purpose: on one hand, it contributes to our understanding of poetry; on the other hand, it offers guidance to poets themselves.

The Poetics implies that poetry is a natural talent, which somewhat undermines its role as a guide. Specifically, Aristotle suggests that analogy, a crucial element of good poetry, cannot be easily taught. Interestingly, the capacity to make apt analogies holds similar significance in philosophy.

Regardless of its intended purpose, the Poetics outlines rules for composition that Greek poets have generally followed. These rules provide a framework for what constitutes successful poetry; they also aim to explain why good poetry is good.

Aristotle believed that the plot plays a central role in achieving poetic impact. It is important to remember that poetry includes Greek dramatic works written in verse. Two overarching themes in Aristotle’s Poetics are naturalness and the distinction between comedy and tragedy.

According to Aristotle, the origin of poetry stems from two human instincts or fundamental capacities. The first is mimesis, which involves representing the world around us. The second is our innate ability for melody and rhythm. For Aristotle, this natural instinct explains the structure of poems and highlights the significance of plot as a foundation for mimesis. If a plot is unbelievable, the poem’s ability to depict reality becomes implausible. Therefore, poetry is considered a part of human nature rather than a divine intervention in the human realm, as Plato once suggested.

If the plot is essential for convincing mimesis, then the tragic plot, characterized by a change of fortune, holds the highest significance. A good plot must meet two requirements: quality and turning points. Quality encompasses sub-requirements such as totality, unity, and generality. The plot should not be overly complex, as it should be easily followed. Aristotle emphasizes that the plot should be of a “fitting size.” However, it is important to note that Aristotle’s notion of following a plot represents only one type of play. Some plots are designed to incorporate ambiguity or intentional confusion. Aristotle’s failure to account for the diverse purposes that a plot can serve highlights his limited understanding of the intentions behind poetic form, narrative structure, and audience reactions.

Trivial and Serious Poets, Epic and Lyric Poetry, Tragedy and Comedy

Let’s examine some of the distinctions that Aristotle makes regarding different types of poetry. He differentiates between laudatory and serious poetry on one hand and denigratory or comedic poetry on the other. Serious poets write about admirable actions, while trivial poets focus on the actions of common individuals.

However, it’s important to note that the notion of the “serious” and “trivial” poet is an authorial projection, as Aristotle acknowledges that certain poets, like Homer, have written both laudatory and denigratory poems. The distinction between the trivial and serious poet is a “fictional possibility” more than a reflection of reality, as Pierre Destrée has argued.

Aristotle proposes two ways of dividing poetry by genre. Initially, there was a distinction between lyric and epic poetry, as discussed earlier, which then gave rise to the further division between tragedy and comedy. The discussion of this latter distinction is one of the reasons why Aristotle’s Poetics continues to hold influence.

Plato and Aristotle on the Cathartic Pleasure of Poetry

Tragedy offers a unique form of pleasure derived from the experience of “pity and fear” evoked by the characters’ plight. To grasp how this constitutes pleasure, it’s crucial to understand that the pleasure Aristotle believes we derive from poetry, in general, is the pleasure of mimesis:

“In case you never saw [a certain] man before, you will not derive any pleasure from his likeness qua representation”

The pleasure of seeing tragic events unfold lies in recognizing something from life in art. It is an emotional pleasure, a catharsis, a reliving and empathizing with a scene. Catharsis involves a connection between the heightened emotions experienced in drama and the genuine emotions we feel toward events in our own lives. Catharsis is, in essence, the purification of pre-existing emotions; by enjoying poetry and theater, we give allow ourselves to process them.

Plato views the pleasure derived from art as transgressive and impermissible since it requires us to surrender to the irrational part of our soul. For this reason, he believed that most art should be suppressed or banned altogether. In contrast, Aristotle sees this surrender as an integral part of leading a fully developed human life. He believes that the specific context of drama or poetry provides a safe space for these irrational or excessive emotions to be experienced. Rather than burdening us in our daily lives, the existence of an artistic context allows these emotions to be explored and expressed safely.

Consequently, the notion of a society banning or eradicating poetry, as proposed by Plato in The Republic, is merely a fantasy. The appreciation humans have for poetry is innate because it relies on two natural instincts: a love for mimesis and a love for rhythm. The innate dispositions of human beings serve as a limitation on potential societal reformations initiated by the state: if they’re going against human nature, they will necessarily fail.