Egypt’s 18th dynasty rose to the start of the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1077 BCE) and was the zenith of Egyptian international power. Many of ancient Egypt’s most notable characters appear during this period, such as Hatshepsut, the female pharaoh, Thutmose III, the empire builder, and Tutankhamun, the boy king. Many rulers from this dynasty left significant marks on the history of not just Egyptian, but world history.

1. Ahmose I

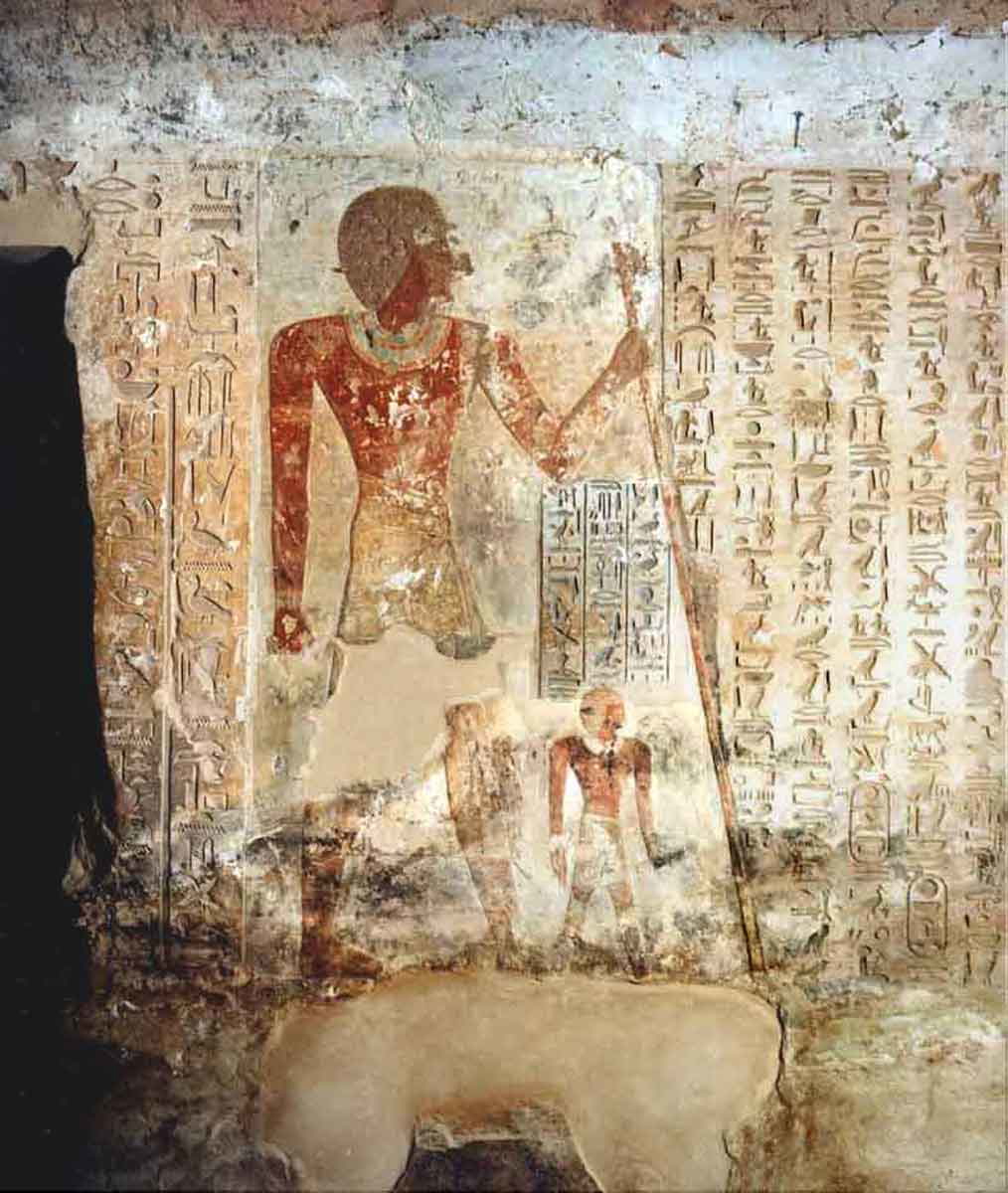

When Ahmose I came to the throne, Egypt had been in a military stalemate with the Hyksos for a decade. After an almost century-long struggle against the Hyksos, who killed his father Seqenenre Tao, Ahmose I’s first priority was to expel the Hyksos from Lower Egypt and restore Theban rule. Ahmose’s mother, Ahhotep, seemingly ruled for several years after Ahmose’s elder brother’s death, but for exactly how long is not clear.

The events leading up to the siege of Avaris, the Hyksos capital, are murky, but artifacts such as the Rhind Papyrus describe some of Ahmose’s tactics. He cut off Avaris from Canaan in a presumed attempt to cut them off from supplies and reinforcements.

The tomb of a soldier also named Ahmose, son of Ebana, contains the most detailed account of the pharaoh’s campaign. His account claims that on Ahmose I’s fourth attack, the city of Avaris fell to the Theban king, He followed this by conquering Sharuhen near Gaza, a Hyksos stronghold. Ahmose I continued to campaign in Canaan to further destroy the Hyksos. Archaeological remains in the area attest to the complete destruction of Hyksos cities at this time. Evidence suggested he campaigned as far as Kedem in Lebanon and possibly into the Levant, setting a standard of expansion and empire building followed by his successors.

Ahmose I also campaigned in Nubia, where he quelled two rebellions and restored Egyptian rule through local princes who were favorable to the Egyptian cause. Back in Egypt, an immense increase was seen in the production of monumental art and architecture, likened to Egyptian society under the pharaohs of old. This reflected the significance of the reunification of Upper and Lower Egypt during his reign. A new era of prosperity, cultural development, and the conclusive expulsion of the Hyksos kickstarted a period of affluence in Egypt. This is why Ahmose I is credited with starting the 18th dynasty and the New Kingdom, despite his brother and father ruling directly before him.

2. Thutmose I

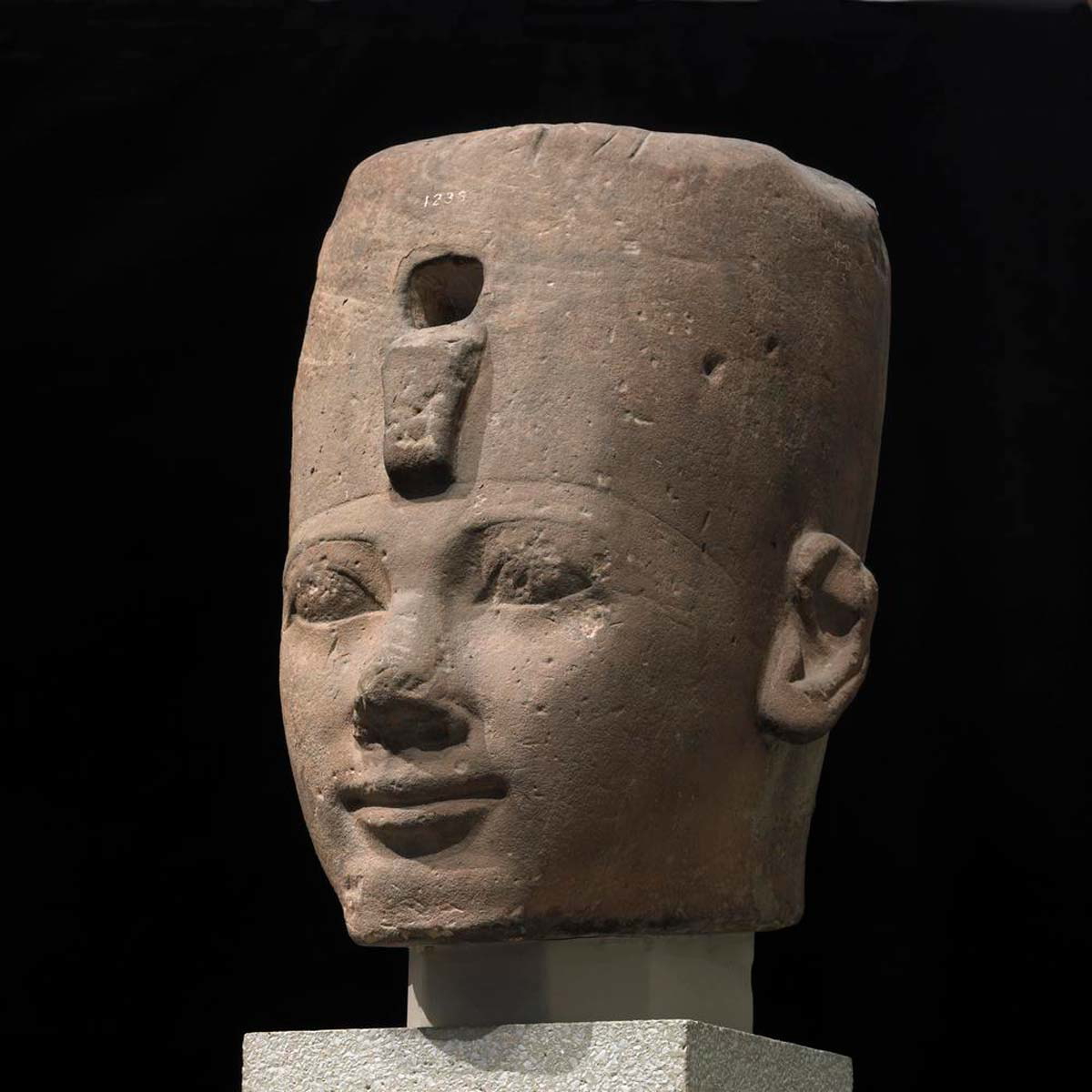

The third Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, Thutmose I, was named as heir to Amenhotep I after the old pharaoh failed to produce any children of his own. Thutmose ascended to the throne when he was already middle-aged, being the first pharaoh to do so for three generations. He was a notable lieutenant under Amenhotep and his reign would be marked by his militaristic approach to kingship.

As soon as he was officially crowned, Thutmose I began exercising Egyptian power over Nubia. Thutmose issued a decree and followed it up with intense military campaigns throughout his second year in office. These campaigns saw him leading his troops to march further than the Fourth Cataract, the furthest that the Egyptians had previously ventured into Kushite territories, decimating the capital of Kerma on the way and killing the Nubian kin.

Thutmose I then set up a new administrative system in Nubia that placed Egypt firmly in control. Governors had to swear allegiance to Egypt, the sons of the Nubian elite were educated in Egypt, and military bases were set up across the land between Egypt and Nubia.

In the victory inscriptions left in Nubia, Thutmose I made it clear that he was ready to expand Egypt’s borders, abandoning the nation’s typical defensive position. It also suggested that he had already led a campaign into Syria. The Pharaoh set his sights on Asia due to previous problems with the Hyksos and the rising Mitanni Kingdom. It seems these campaigns were not aimed at bringing foreign lands into the empire, but to continue the destruction of Hyksos strongholds and strike up allegiances. Notably, on his return from the east, Thutmose celebrated by hunting elephants and talked of the “strange” Euphrates River that flowed in the opposite direction to the Nile, which became known as the “inverted river.”

As well as his impressive military efforts, Thutmose I is equally remembered for his remarkable building projects. He was the first pharaoh to work on the Temple of Karnak, including the construction of the Fifth Pylon, which set a standard for his successors. Likewise, he was the first pharaoh to be buried in the Valley of the Kings and established the community of artisans and workers in Deir el-Medina to construct the tombs. His tomb in the valley is KV38, although his body may have been moved to KV20.

3. Hatshepsut

Originally the Great Royal Wife of Thutmose II, Hatshepsut ruled largely independently as Queen Regent and then as Pharaoh for many years whilst technically being co-ruler with her stepson, Thutmose III. She was the daughter of Thutmose I and married her half-brother Thutmose II around the age of 14 (although this is disputed). When her husband died in 1479 BCE, Thutmose III was only two years old, so Hatshepsut ruled initially as regent. But by year seven of Thutmose III’s reign, she assumed all pharaonic titulary to become co-ruler with him. Historians have debated her motivations for doing so. The view has shifted from a simple desire for power to the need to stabilize the throne due to the weakness of having a child pharaoh.

Hatshepsut’s strategy to legitimize her controversial position on the throne was one of monumental architecture, cultural prosperity, and self-promotion. She successfully reinvented her image to one of androgyny, whereby she was sometimes portrayed as a male pharaoh complete with beard and muscles or as a traditional Egyptian royal woman. Moreover, she maintained close alliances in court, advocated a narrative of divine birth, and proclaimed herself as the heir of her father.

Her reign was one of peace, which is demonstrated by her affluent building projects. Not only were they grand but also incredibly numerous with hundreds of temples and other monuments constructed or refurbished, including many that were destroyed by the Hyksos. Most noteworthy are perhaps her additions to the Karnak site including four great Obelisks, the Temple of Pakhet (two lioness war goddesses), and her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari.

Additionally, Hatshepsut reestablished multiple trade routes that had been out of use due to Egyptian issues with the Hyksos. She visited the Land of Punt herself and brought back lavish goods. Thus, Hatshepsut proved that she did not need to go to war to expand the Egyptian sphere of influence, despite rumored skirmishes with Nubia.

The infamous iconoclastic attack on Hatshepsut many years after her death has fuelled historical gossip and confused experts. Pharaonic iconoclasm is the attempt to remove a pharaoh from memory or the historical record. The attempted erasure of Hatshepsut is usually ascribed to her stepson and successor Thutmose III, as some sort of vengeance for making him wait so long to rule on his own. However, historians have more recently proposed that it may have been the doing of the son of Thutmose III, pharaoh Amenhotep II, as it would have strengthened his claim to the throne. Seemingly, any destruction of Hatshepsut’s name, image, or monuments came right at the end of Thutmose III’s reign, when Amenhotep would have been around eighteen years of age. His reign saw him crediting many of Hatshepsut’s accomplishments to himself.

4. Thutmose III

Thutmose III assumed the throne independently at around twenty-two years old. As co-regent with Hatshepsut, he spent most of his time training with the military before heading Hatshepsut’s armies. When he became sole pharaoh after Hatshepsut’s passing, he focused on military expansion and was notoriously successful in these exploits. Thutmose III is widely regarded as one of the greatest military tacticians in history as he led at least 16 successful military campaigns. Most of what we know today comes from the Annals of Thutmose III, an in-depth account of the pharaoh’s imperialist achievements and the most detailed account of any pharaonic reign.

Thutmose III’s first military expedition took place immediately upon the death of Hatshepsut when Canaanite forces, led by the King of Kadesh (or Qadesh) moved closer to Egypt and gathered at Megiddo. Thutmose surprised them by picking the precarious Aruna route through the mountains as opposed to the two obvious routes around them. The Egyptian troops emerged through the pass and caught the Canaanite army by surprise. After a brief battle, in which the inexperienced Egyptian forces were distracted by looting the Canaanite camp, the Canaanites retreated to the city of Megiddo. A siege took place over seven months and, despite the King of Kadesh escaping, the Egyptians were successful, and also conquered other cities and sites in the area.

Thutmose took the sons of the defeated king hostage so they would receive an Egyptian education and return to their homelands with sympathetic views of Egypt. Other kings, such as the kings of Assyria, Babylon, Cyprus, and the Hittite king, all sent gifts to Thutmose III, demonstrating Egypt’s powerful position in the Near East. Thutmose III expanded the Egyptian Empire to its greatest size ever.

Thutmose continued to campaign in the Near East and took cities and ports into the Egyptian sphere. He established garrisons that were important for Egyptian trade and took hostages from rebelling people. Thutmose made it as far as the lands of Carchemish and Aleppo, and attacked the unsuspecting kingdom of Mitanni. People often dub Thutmose III and Egyptian Napoleon, but unlike the French emperor, he never lost a battle. At home in Egypt, Thutmose continued with grand building projects, including the construction of at least fifty temples. He added Pylon VI, Pylon VII, Pylon VIII, and a jubilee hall to the temple complex at Karnak.

5. Akhenaten/Amenhotep IV

A century after Thutmose III ruled Egypt, Akhenaten ascended to the throne as Amenhotep IV, the tenth Pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. His age at this time has been theorized to be anywhere between 10 and 23. Amenhotep IV began his reign the same as any of the previous 18th dynasty pharaohs. He erected monuments and inscriptions in the typical artistic style and worshiped the traditional Egyptian deities. However, sometime in year five of his reign, he changed his name to Akhenaten. Shortly after that, he began building his new capital city, today known as Armana.

Amenhotep IV’s name change to Akhenaten signified an enormous shift in his religious beliefs. He ended his association (via his name at least at this point) with Amun, the important patron deity of Thebes and god of sun and air. He instead connected himself to Aten, a lesser sun god, said to specifically embody the disk and rays of the sun. Swiftly after, Akhenaten constructed his new capital city of Akhetaten, meaning “Horizon of Aten.” New blocks that were smaller than those used in construction previously enabled the city to be erected much quicker than before. This new site contained the Great Temple of Aten as well as royal residences and official offices, and was full of beautiful villas, all in a new artistic style.

The Amarna period artistic style is demonstrated through several famous artworks, such as the seemingly realistic bust of his Great Wife, Nefertiti, and multiple statues of Akhenaten himself. Similarly, the Amarna letters, a collection of 382 clay tablets of correspondence between Egypt and other contemporary states such as Assyria, Babylon, Canaan, and Syria, were found at the site. Interestingly, they were written in cuneiform. These tablets reveal great amounts about society, individual people, and politics at the time, and potentially contain the first mention of the Hebrews.

However, Akhenaten’s reign was noticeably less successful than his predecessors. Trade with foreign states declined and he took little notice of the army and navy, which had been imperative in securing Egypt’s international interests up until that point. Instability allowed for corruption in local government systems and officials regularly took advantage of their positions to take tax money for themselves. Moreover, Akhenaten’s new religion was unpopular with the masses. He abandoned the funerary cult of Osiris, had many temples dedicated to the old gods closed, and ordered the erasure of Amun from monuments.

After his death, Egypt gradually reverted to Egypt’s traditional religion. Historians suggest that under Akhenaten’s first two successors, both religions coexisted.

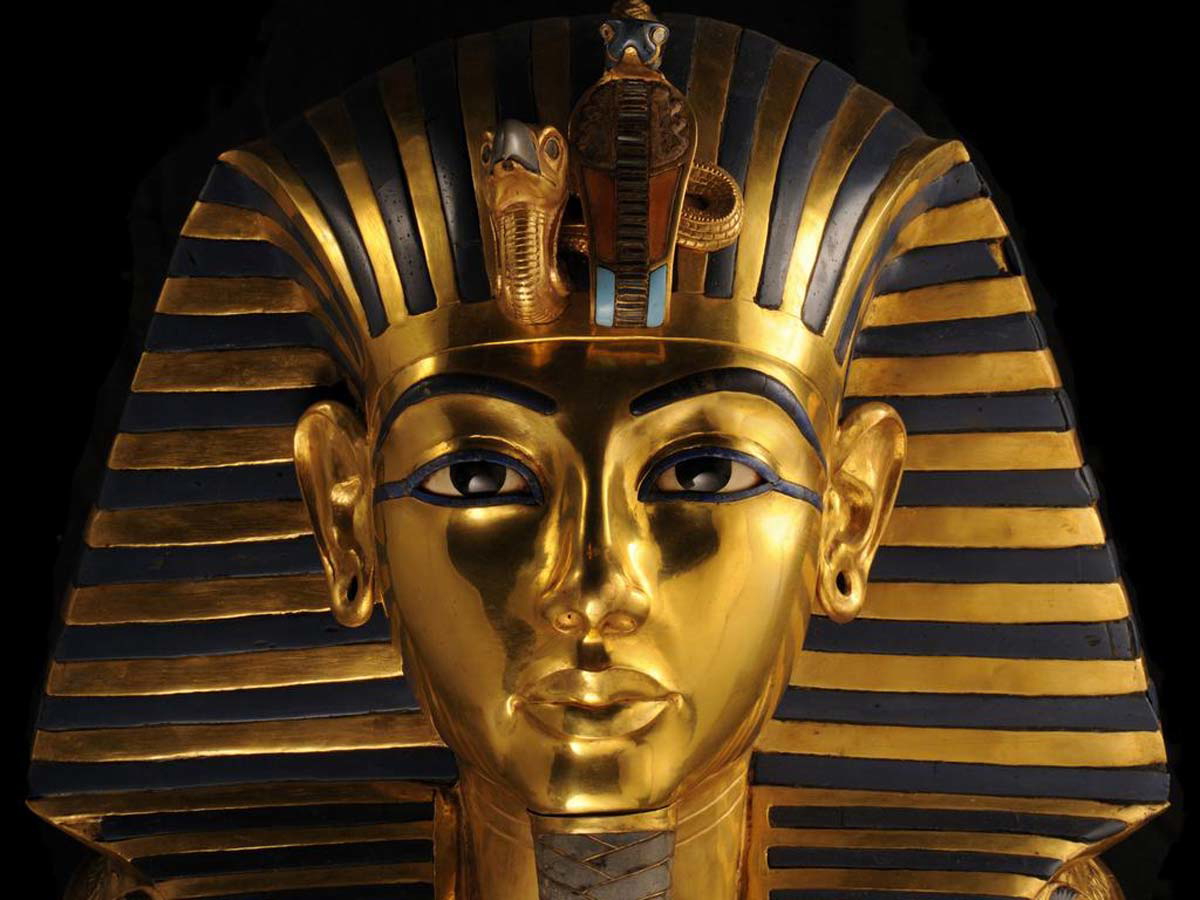

6. Tutankhamun

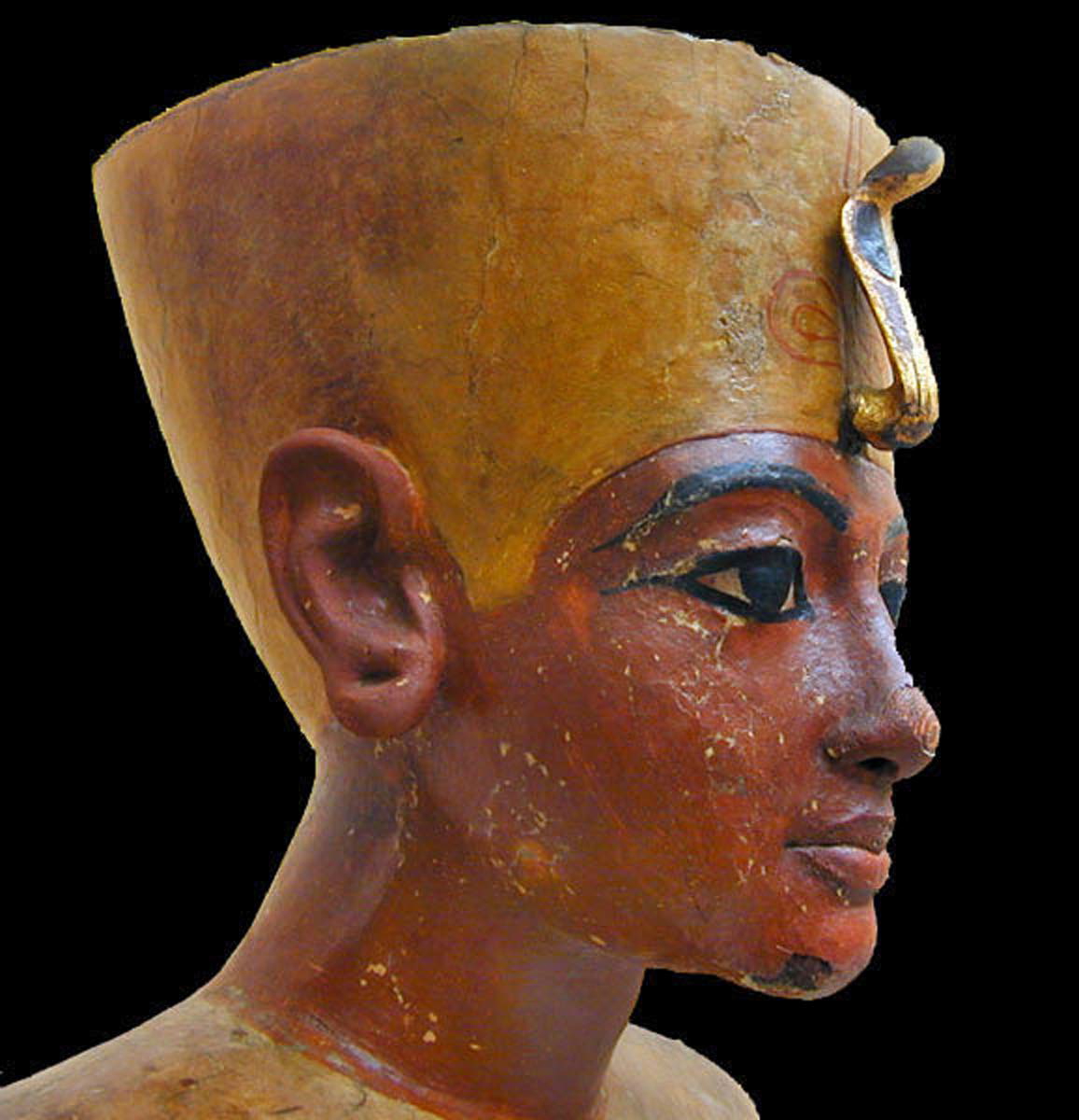

Tutankhamun became pharaoh aged just nine years old after the tumultuous and short-lived reigns of Smenkhkare and Neferneferuaten. One of these rules may have been Nefertiti, or the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti and the wife of Smenkhkare. The information regarding these two rulers is confusing at best, with both sharing dates and similar titles. Consequently, historians cannot conclusively date either.

It is most likely that Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten, and DNA evidence from the mummies found in the Valley of the Kings appears to corroborate this. His first order of business seems to have been the integration of Atenism into the traditional Egyptian religion. He also had many of Akhenaten’s other policies reversed to restore stability. Notably, by the third year of his reign, he had changed his name from Tutankhaten to Tutankhamun, which realigned himself with Amun and his powerful priesthood. The young pharaoh also began rebuilding temples and reinstating priests.

Quickly after this, the administrative hub of Egypt was moved from Akhetaten back to Memphis. Tutankhamun attempted to restore favorable relations with foreign powers that had declined under Akhenaten, but ended up going to war in the Near East and faced rebellions from the Nubians.

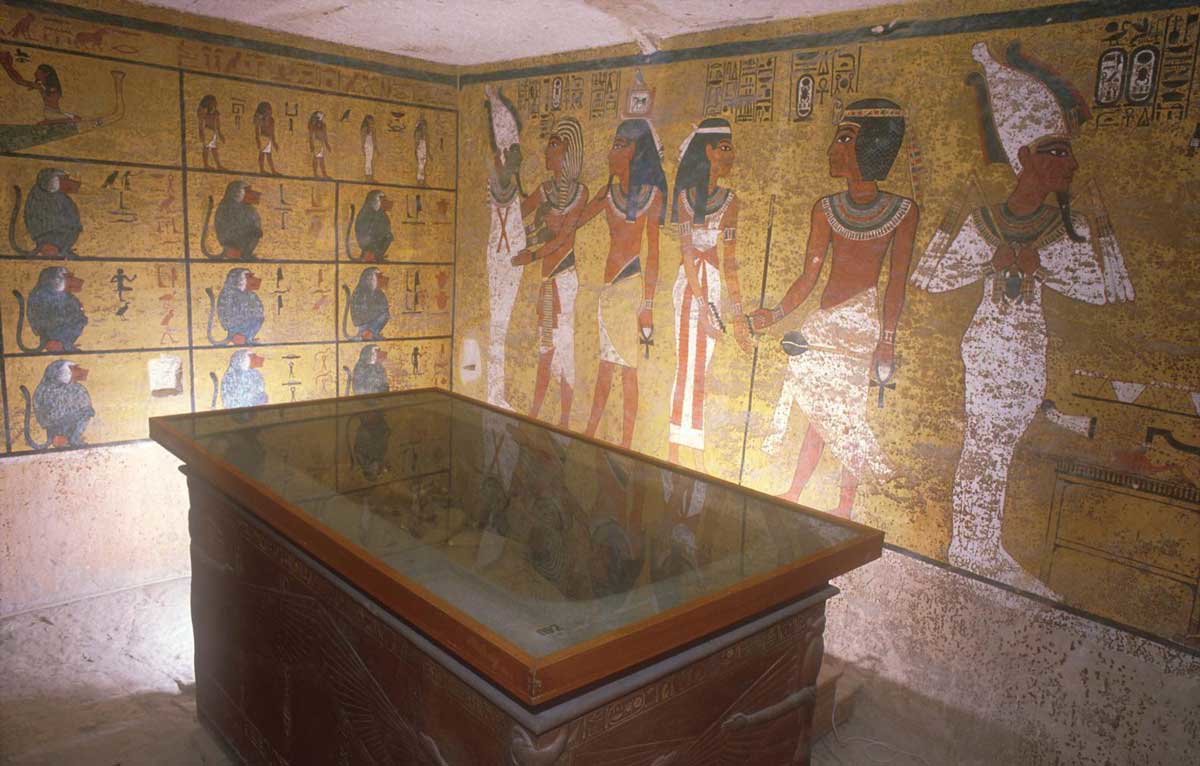

His participation in such battles has been the subject of disagreements among historians since his tomb was discovered. There were multiple weapons found in the tomb and many effigies of the young king in battle adorn his tomb and sarcophagus, suggesting the young king was a warrior. But his supposed disability and its disputed level of severity, as well as his young age, has led experts to think the imagery of Tutankhamun as a warrior is largely symbolic.

Akin to the reigns of his predecessors, Tutankhamun began huge construction projects, but most were incomplete or usurped by later pharaohs. He also usurped monuments built by Akhenaten, such as the sphinxes at Karnak, which he changed to have the heads of rams in honor of the god Amun-Ra. Materials were repurposed from the temples built under Akhenaten dedicated to the god Aten for a new temple dedicated to Amun, which further demonstrates Tutankhamun’s desire to separate himself from Akhenaten and the religion of Atenism.

Tutankhamun’s cause of death is a mystery. The infamous theory of a blow to the head was debunked by scientists and many point to sickle cell anemia or other health disorders. Regardless, upon his death, he seemingly had no living heirs. He appears to have made provisions for Horemheb, an advisor to and commander of the army, to become the next pharaoh. Evidence suggests that Egypt may have been at war with the Hittites at the time of Tutankhamun’s death, therefore Horemheb would have been leading the Egyptian army in the Near East, resulting in a power vacuum in the line of succession.

7. Horemheb

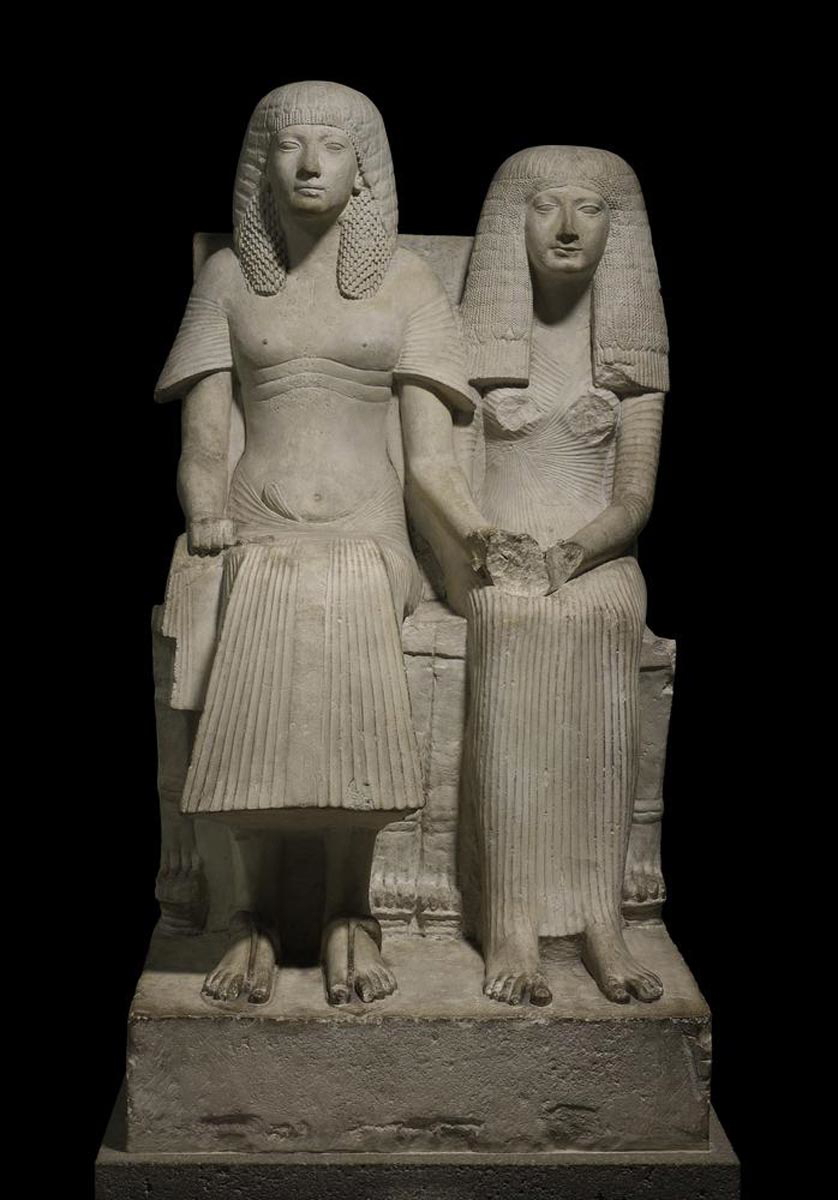

The final pharaoh of the 18th dynasty, Horemheb came to power after the death of Ay, who had been an advisor to Tutankhamun and Akhenaten and had opportunistically seized the throne during Horemheb’s absence by marrying Tutankhamun’s widow and performing his funerary rites. Upon Ay’s own death, he had placed his son (or possibly adopted son) next in line for the throne, but this never came to be. Horemheb began his reign by erasing Ay’s name from monuments and supposedly smashing his sarcophagus. Horemheb possessed no royal relation and may have been of common birth. The earliest evidence shows Horemheb depicting himself as a royal spokesman handling affairs in Nubia before rising to head of the army.

Early in his reign, Horemheb was still faced with the aftermath of Akhenaten’s rule and began internal reforms to address the instability. To strengthen his position, he put men from the army who were loyal to him in powerful positions, particularly within the all-powerful cult of Amun. He also married Mutnodjmet, who historians believe to be Nefertiti’s younger sister. He held great coronation celebrations all over the country to garner popularity with the people. The Edict of Horemheb further demonstrated his dedication to the eradication of corruption within the government and elite classes with the introduction of extreme punishments for those found guilty, including beatings, being sent to the frontline, and even execution.

Horemheb was another prolific builder and constructed Pylon II, Pylon IX, and Pylon X of the Great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak. He notably used materials from monuments built by Akhenaten. He also built a temple dedicated to the god Seth and a temple at Gebel el-Silsila in Nubia, which contained depictions of himself and 75 Egyptian deities.

During Horemheb’s 14-year term as pharaoh, Egypt regained power and stability. However, neither of his known wives provided him with an heir, although scientists have deduced from the mummy of Mutnodjmet that she may have died in childbirth. Horemheb chose Paramesse, a vizier, as his successor. This was partially due to Paramesse’s loyalty to Horemheb, and because he already had a son and a grandson to limit the possibility of more Egyptian internal struggles.

Upon his ascension to the throne, Paramesse assumed the name Ramesses I and kick-started the 19th dynasty. Additionally, his son and successor, Seti I, was possibly married to a daughter of Horemheb.

In conclusion, Horemheb was able to rectify the chaos caused by the Amarna period and create a new and powerful dynasty of pharaohs, which included Ramesses II or Ramesses the Great. Yet, the continuous and largely unwavering power of the 18th dynasty would not be felt again. Egypt soon entered a period of decline due to internal factions and the increasing might of Near Eastern Empires.