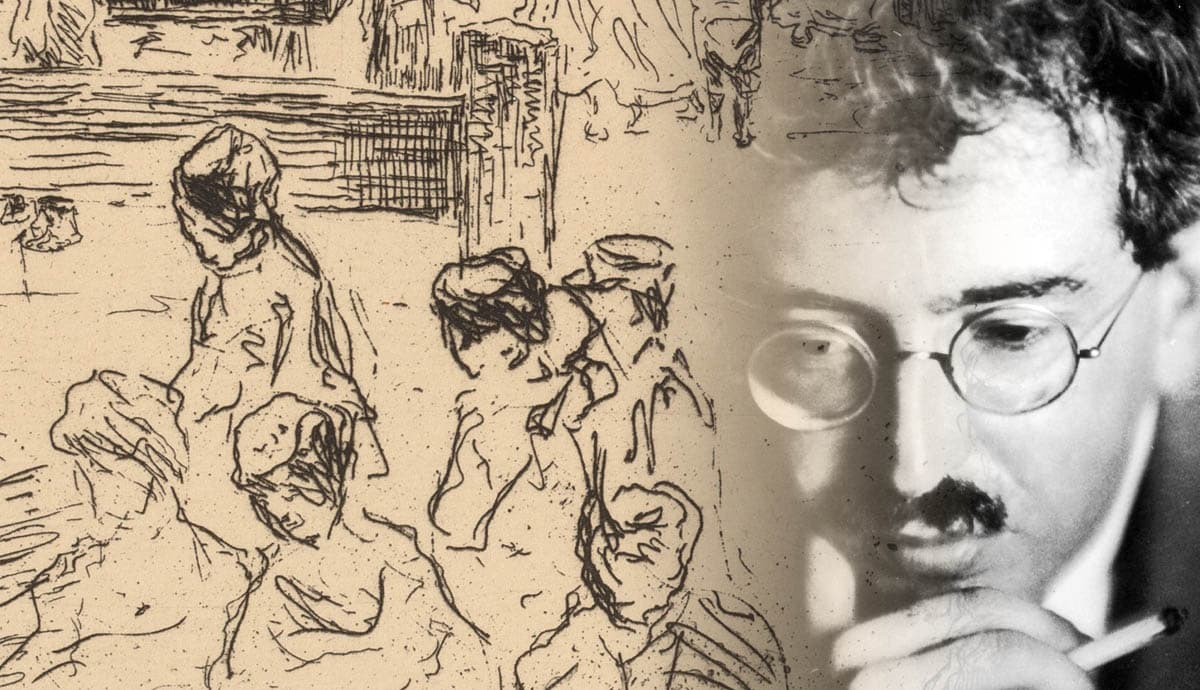

Walter Benjamin was one of the most influential contributors to Critical Theory. His ideas and ideology deep-dived into truths about society, interconnecting different facets of human endeavor, from politics to art. Walter Benjamin is a philosopher who got to live through extraordinary times: born at the end of the 19th century, he saw the mass growth and expansion of several key industries – from car manufacturing to the advent of film.

Walter Benjamin: An Elusive Thinker

Walter Benjamin’s works range from topics like Phantasmagoria, a concept that was much more common in his time than it is today, to art criticism, all the way to discussions of translation theory. Oftentimes Benjamin would bounce back and forth using examples from all sorts of categories to build a broader picture for the reader, creating a fun and unique experience for studying philosophy. Many more well-known philosophers, such as Habermas and Derrida, would reference Benjamin’s work and his influence on Critical Theory. During the Interwar Period in Germany he was able to find a group of like-minded individuals at The Institute for Social Research. This group of extraordinary thinkers would go on to be called The Frankfurt School.

The Frankfurt School: Finding Inspiration

The Frankfurt School was a large conglomeration of like-minded individuals who attempted to build a wider understanding of the social construction and development that was happening all around them. Walter Benjamin’s close relationship with Theodor Adorno, also a member of The Frankfurt School, is what originally drew him into the school. The study and ideas coming out of the school often directly concerned the rising fascist movement that was forming in Germany at the time.

The changing times and the introduction of new technological marvels seemed to be a constant during Walter Benjamin’s early 20s and well into his 30s. These advances were a source of inspiration for his philosophy. The introduction of moving pictures and film was particularly fascinating to Benjamin. While this fantastical growth in technology was occurring, a dark side of politics and society was rising, too. Like many other scholars of the Frankfurt School, Walter Benjamin was a Jewish German citizen, and one that would be labeled a political dissident in the late 1930s. Due to his influential work in art theory, Benjamin became an enemy of particular note to Hitler and his Nazi Party.

Revolutionary Times: Benjamin’s Tragic End

In 1932 the revolution in Germany that led to the ascension of Hitler to power was unfolding. Fearful for his future, Walter Benjamin fled Germany and settled in France. He would go on to live in and around Paris for the next 5 years. Benjamin ran out of money during this time but was funded by Max Horkheimer, another member of the Frankfurt School. During this time he met and befriended other influential scholars such as Hannah Arendt, who had also fled Nazi Germany. While in exile, he published his most famous work: Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. He also entrusted his work The Arcades Project to other philosophers from the Frankfurt School, a work that labeled 20th century Paris as the center of the emerging new world and an influence upon nearly all facets of society.

In 1940 Benjamin and his family had to flee from Paris as the German Army fell upon France. The German Army had a specific warrant for the arrest of Walter Benjamin in his apartment, upon entering Paris. Benjamin’s plan was to travel to the United States via the then neutral Portugal, but unfortunately never managed to make it there. Walter Benjamin made it as far as Catalonia in Spain, just outside of France. Shortly after crossing the border, the French police – now under German control – canceled all travel visas and demanded the immediate return of all immigrants from Spain, particularly the Jewish refugee group Benjamin was a part of.

On September 26th, 1940 Walter Benjamin committed suicide in a hotel room. Another member of the Frankfurt School, Arthur Koestler, also attempted suicide there yet was unsuccessful. The remainder of the group were allowed to continue out of Spain to Portugal. Unfortunately, Benjamin’s brother George died at the Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in 1942. Thankfully, Benjamin’s work The Arcades Project saw the light of day after his copy was given to The Frankfurt School. It is speculated that he had completed another work that went missing in the turmoil of his death, though it is speculated that it could have just been a finalized version of The Arcades Project.

Art and the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Diving deeper into Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin discusses how the reproduction of art has demystified the purpose of the art. Benjamin theorizes that the purpose and goal of art is that of presence, the shared moment between the observer and the piece of art. He describes a very specific aura that is achieved at that moment.

This critique of artwork that Walter Benjamin offered in his work presented a novel perspective. While society had had access to print and books for a long time by the 20th century, access to widespread photography via newspapers and journals created an unprecedented access to art. This access took away the majesty and presence that Benjamin found so endearing within an artwork. Justifying art and recognizing its purpose became more difficult as technology brought us closer together yet farther from the specific aura of art.

20th Century: Movements Toward Mass distribution

Walter Benjamin witnessed the wide-scale implementation of mass production and distribution in all aspects of society. He saw the rise of ads and film and newspapers, as well as the rise of mechanical industries flourishing in factories. This mass distribution of goods and commodities to more people than ever was revolutionary and beneficial in the eyes of Walter Benjamin. Many of his colleagues at the Frankfurt School who happened to be socialists or Marxists also saw the benefits to this new distribution, as it provided wider access to items that used to be reserved for the upper classes.

This distribution of goods also led to a distribution of art and knowledge, both of which Benjamin took to critiquing. One of Walter Benjamin’s works specifically talked about this commodification of knowledge, The Task of the Translator. He discussed the role and responsibility of translating a work. While it might seem obvious to some that simply substituting German words for French ones would be the role of the translator, Benjamin points out that allegories, comparisons or examples in more complex works actually require an investigation into their deeper entrenched meaning.

Walter Benjamin had several of his own works translated from their original German to French, as he was residing in France near the end of his life. His works were later translated further into English. It is interesting that these manifold translations have since resulted in slightly different titles for his work Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, providing an example for his work The Task of the Translator.

Technology and Looking Backwards: The Printing Press

Walter Benjamin regularly used examples from the past within his works. He was interested in how production has changed in the past. For example, the Gutenberg Press changed storytelling for all of society, and exemplifies one of the first massive changes in how information and art were distributed to everyone.

For much of history, storytelling was a group affair. People would gather around a storyteller or orator who would give out information, oftentimes about society or myths that people already knew. Yet these stories were different every time they were told and they often pandered directly to the people they were being told to. It could be unwise to tell a joyous story describing the feasts and privileges of a monarch to a group of oppressed and starving people: their anger could end up affecting the storyteller or orator. Walter Benjamin noticed that after the Gutenberg Press revolutionized storytelling, forcing it into the format of the novel, the experience of storytelling became incredibly individualized and personal. Stories are now enjoyed in a quiet, private space instead of in a public one. This is an example of how technology can directly affect people’s relationship to art and knowledge, and an omen of how technology would inevitably change it again in the future.

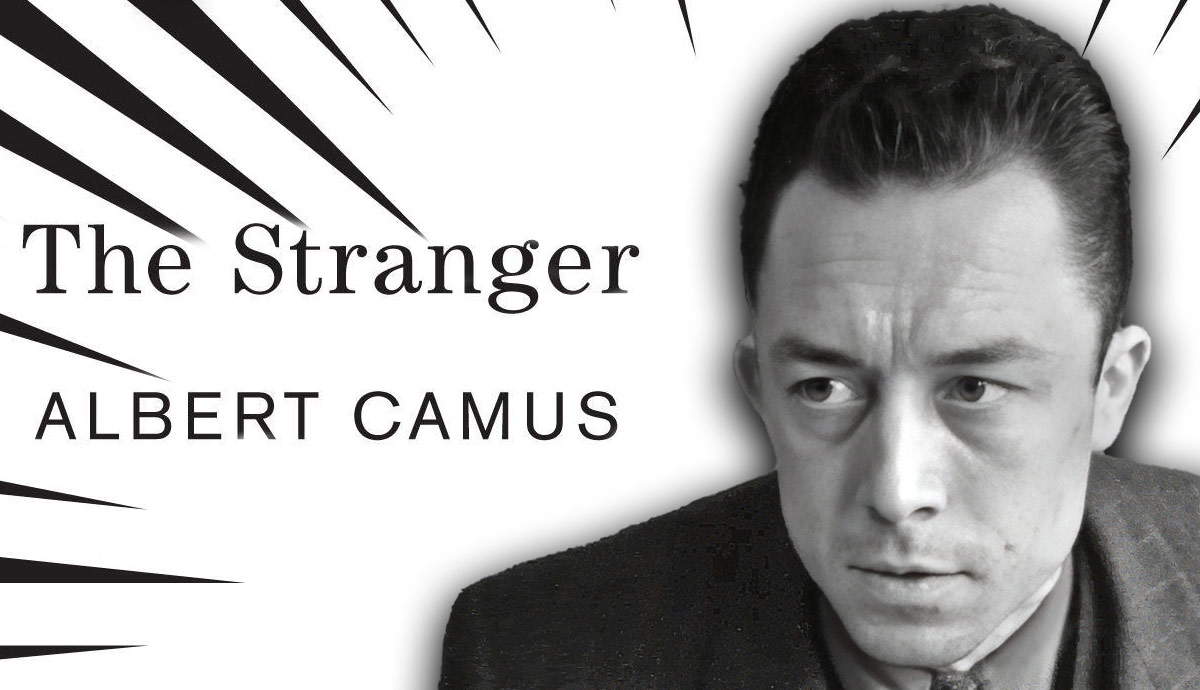

Technology and Looking Forward: The Advent of Film

Looking into the future, Walter Benjamin referenced the mass changes he saw during his life. Specifically, the film industry was occupying the space of stories and storytelling and bringing it back to the masses. For the first time in several centuries, storytelling went from being an individual experience to becoming a group affair: showing up to the theater and enjoying a movie together. As a group, you would participate in the simultaneous and collective enjoyment or horror of the story. Then these groups would be able to discuss the story together afterward, freshly affected by it, a very different process from the individual enjoyment of reading.

Walter Benjamin believed that this process would inevitably lead us back to individualization. Though he could not imagine how technology would change he believed that film would eventually become something that was done in seclusion, in the privacy of one’s own home. Similarly to what happened to stories after the invention of the printing press, we now know that this process did occur. I doubt Benjamin, or anyone else for that matter, could have imagined the effects of something as vastly influential as the internet and online forums for discussions of things like Netflix, but it is still important to reflect on the influence of technology on our practices. We should take Benjamin’s work and ideology to try to interpret the world around us, and maybe even predict what could happen through this constant ebb and flow that moves our practices from the individual, to the collective, to the individual again.

Distraction as a Reaction to the Modern World

Walter Benjamin’s last work The Arcades Project, which was saved by members of the FrankfutSchool, was specifically about the culture and impact of Parisian life on 20th century society. As we have mentioned in passing, Benjamin’s obsession with film actually stemmed from something that people of the early 1900s would be very familiar with: Phantasmagoria Theater. Phantasmagoria was an invention that projected images onto a wall with the aid of lanterns, transparent materials and smoke. Some projections could even involve several images, giving the appearance of a moving image. Phantasmagoria Theater often took place in catacombs or other small confined and scary places around Paris where these groups would be told a story and then shown these scary images which seemed to appear from nowhere.

This precursor to what we know as the projector and film was a mind-bending experience for people in the 19th century, as they had never seen anything like it before. The impact was a change in society’s perception. Yet it came at a cost: this new and more in-depth sensory experience was an overstimulating bombardment of experience for the everyday person at the time, and it led to a sort of distraction. This distraction was a keyword in Benjamin’s work, who used it to present a critique of society and culture. While technological changes made many things more accessible, no one was discussing how to deal with such changes on a social level. This issue is presenting itself in an even more marked way today.

Walter Benjamin: Phantasmagoria of Philosophy

Who knows if, given the time, we would have seen an expansion of Walter Benjamin’s philosophy to the issues of distraction within contemporary society? Unfortunately, due to the rise and threat of nationalism in Germany and the hatred that cut Walter Benjamin’s life short, we will never know. We can, however, look thoroughly at his work and use it to better understand how society affects art, knowledge, and our understanding of society. We can try to individuate our times’ Phantasmagoria and build a philosophy around it, working to deal with the problems we face and planning for what will come in the future. Walter Benjamin and The Frankfurt School sacrificed so much to give us a framework of understanding; where we take it from here is up to us.