The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World were a collection of structures admired by ancient Greek writers and travelers as feats of beauty and human engineering. Ancient authors such as Diodorus Siculus and Antipater of Sidon compiled lists of these “sights to be seen,” but the list we reference today was solidified from their suggestions during the Renaissance, when only one of the ancient wonders was still standing. Read on to discover the seven wonders of the ancient world and what happened to them.

1. Great Pyramid of Giza (Egypt)

The Great Pyramid of Giza is the only ancient wonder still standing. Constructed in the 2500s BCE during Egypt’s 4th Dynasty, the Pyramids are grand structures on the Giza Plateau built by three generations of monumental pyramid builders. The Great Pyramid was the first and largest built by the pharaoh Khufu, called Cheops by Herodotus. The second largest pyramid was built by his son Khafre, who most Egyptologists also believe constructed the Sphinx, while the third and smallest was built by Khafre’s son Menkaure.

Designed as the final resting places for the dead pharaohs, they originally gleamed in shining white limestone with golden capstones. While elements of their construction remain mysterious, archaeology reveals that the Egyptians could mobilize a talented, well-paid labor force, with neither an army of slaves nor aliens playing a part.

Like almost all royal burials in Egypt, the Pyramids were robbed millennia ago. Most likely, they were picked clean during the First Intermediate Period that followed the collapse of Egypt’s Old Kingdom in the 2200s BCE. The Pyramids acted as tempting beacons for plunderers, and their failure to protect their occupants might explain the later shift to less conspicuous tombs like those in the Valley of the Kings. Time and scavenging took away the limestone casings and golden capstones, leaving the rough stone exteriors that we see today. Nevertheless, they are some of the most recognizable structures on earth and are a testament to the immense power of the pharaohs 4,000 years ago.

2. Mausoleum of Halicarnassus (Anatolia)

The Mausoleum of Halicarnassus was built in the city of Halicarnassus on the Western coast of modern-day Turkey in the mid-4th century BCE for the Carian king Mausolus and his family. It was started before his death and finished posthumously on the orders of his sister-wife Artemisia II, whose immense grief has been the subject of art for millennia.

The Mausoleum was a towering 45-metre structure containing over 400 sculptures from some of the finest sculptors in the Greek world. It was topped by a pyramid upon which Mausolus and Artemisia rode in a four-horse chariot. Pliny the Elder, Strabo, Vitruvius, and others described its magnificent beauty. These descriptions and the fragmentary remains of a handful of the statues are all that remain. It was still standing in the Roman period, but fell into ruin sometime before 1402, when crusading knights cannibalized its remains for stones to build the nearby Bodrum Castle.

3. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (Asia Minor)

The Temple of Artemis at the former Greek city of Ephesus was a grand structure dedicated to Artemis, the Greek goddess of the hunt. She was the patron goddess of Ephesus, and they honored her in the same way Athens honored their patron Athena with the Parthenon.

The Temple of Artemis was actually three temples, built and destroyed at separate times. The date of the construction of the first temple is unknown, but it was destroyed by a flood in the 7th century BCE. It was rebuilt larger with slight design changes soon after, only to burn down in 356 BCE due to arson by a man named Herostratus. This was around the time of Alexander the Great’s birth in Macedonia. Plutarch suggests that the temple burned because the gods were distracted by Alexander’s arrival.

The third and final form of the temple was built in the late 4th century BCE, with an impressive number of peripheral columns. This temple endured for centuries and informed modern images of it. This temple was severely damaged by Gothic raids in the 3rd century CE, and it was fully demolished by Christians in the late 4th century. The site was lost for years until a British expedition rediscovered it. Today, a single column assembled from disparate fragments uncovered at the site is all that stands on the site.

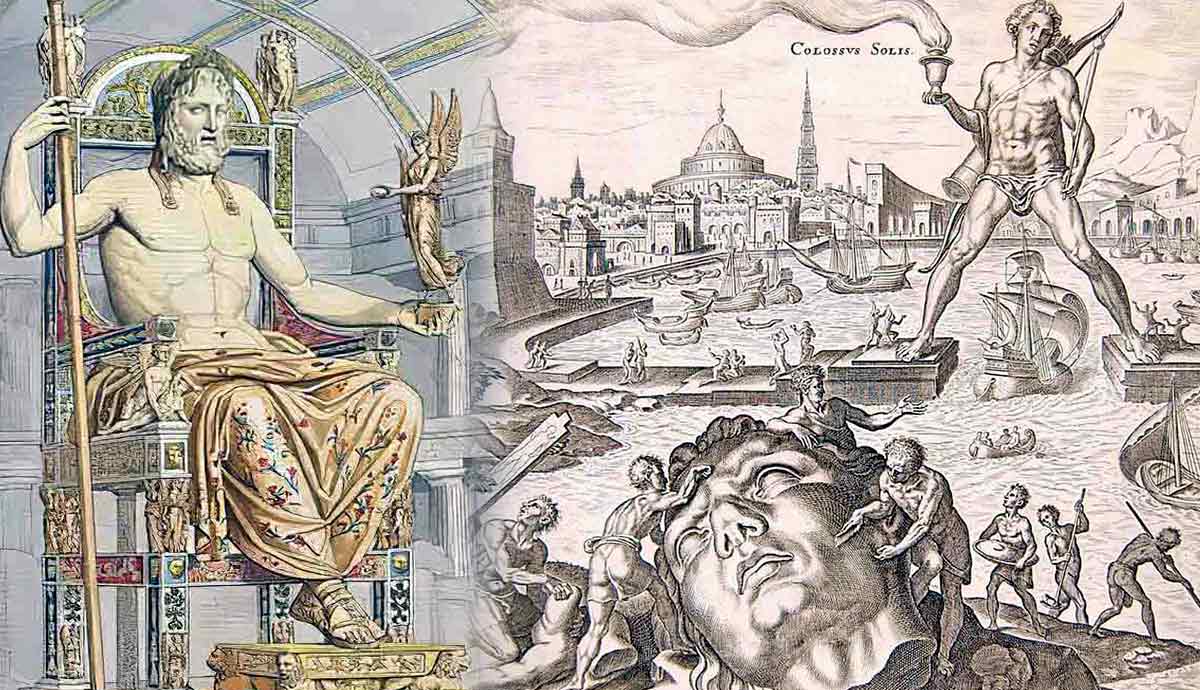

4. Statue of Zeus at Olympia (Greece)

Zeus was the most important of the Greek gods, and the massive Statue of Zeus at Olympia was his most famous image. The statue was made of wood covered in gold and ivory plates. Seated on a massive throne, the statue was 14 meters tall, the god’s head almost touching the ceiling of his temple. It was created in the 5th century BCE by the famous Greek architect Phidias, who also created the enormous statue of Athena Parthenos.

The statue is one of the hardest wonders to trace through the historical record. It was still at Olympia in 391 CE when Theodosius I closed all pagan temples in the Roman Empire, but there’s no clear record afterwards. It was most likely destroyed when the temple itself burned down in the 400s. There is a wild story that it was secretly hidden away in Constantinople, where it was reassembled before being burned again, but there is no supporting evidence.

5. Colossus of Rhodes (Greece)

Also honoring their patron deity, the city of Rhodes created an enormous statue of the god Helios, which became known as the Colossus of Rhodes. Standing 33 meters tall, the bronze statue towered over the harbor of the maritime nation. Historians are unsure of its precise location in the harbor, how exactly it was made, and even the pose it was cast in, but that hasn’t stopped artists recreating the image for millennia.

The statue was built in the 280s BCE to celebrate the defeat of Demetrius Poliorcetes during the Siege of Rhodes from 305-304 BCE. It was allegedly paid for by selling off their enemy’s abandoned siege equipment. It took 12 years to build, but in 226 BCE, just 54 years after its completion, a devastating earthquake toppled the colossus. Despite the Ptolemies of Egypt offering to help reconstruct the colossus, Rhodes interpreted its destruction as a sign of divine disfavor and never repaired it.

The Colossus lay where it fell for centuries and still inspired awe in visitors. Its ultimate fate is unknown. It probably degraded over time with the locals scavenging its metal. It was certainly gone by the late 650s CE. One source accuses Muslims of selling the remains of the statue shortly after their conquest of the island in 653, but little, if anything, probably remained by that point.

6. Lighthouse of Alexandria (Egypt)

While most of the wonders served religious purposes, the Lighthouse of Alexandria was a practical construction. Situated on the island of Pharos, which is also the ancient name of the lighthouse, it served Alexandria’s bustling maritime industry. The soaring 100-meter-tall structure was built on the orders of Ptolemy II to support the increasingly important port. It was one of several incredible monuments that defined the new capital of Ptolemaic Egypt, including the famous Library of Alexandria and the Tomb of Alexander the Great. The Lighthouse remained in use for centuries, surviving multiple invasions, earthquakes, and foreign occupations.

However, those earthquakes would eventually cause its downfall. The first major structural damage occurred in 956 and forced the city’s authorities to conduct significant repairs. It suffered serious damage again in 1303 and 1323, which toppled the bulk of the structure and left it completely defunct. It was finally removed in 1480 when the Mamluks cleared the base and used the stones to build the Citadel Qaitbay on the site. Remnants of the lighthouse still lie in the shallow waters near where it once stood, its barnacle-encrusted bones surviving as a grim legacy.

7. The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The final wonder was the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, which may never have existed at all. Supposedly, they were built by Nebuchadnezzar II, one of Babylon’s finest kings, during the 7th century BCE. Sources suggest it was a towering structure with multiple tiers full of a vast array of plant life, sustained by elaborate irrigation works. This combination of beauty and engineering prowess was what earned the Gardens their spot among the seven wonders.

However, while several ancient writers talk about the Gardens, all accounts are second-hand; none of the surviving writers ever saw them. The Gardens are curiously not mentioned by many sources that discuss Babylon, such as Herodotus or surviving historical accounts of Alexander the Great, who made his capital in the city. There are also no Babylonian texts indicating the existence of the Gardens, nor any trace of them at the modern archaeological site of Babylon.

Some believe that the Gardens existed in as-yet unexcavated parts of the city. Another theory suggests that the Gardens, only ever attested by Greeks who never visited Mesopotamia, are a corrupted miscommunication of real gardens built by the Assyrian King Sennacherib elsewhere in Nineveh. This Assyrian Garden is supported by archaeological evidence, and its descriptions of marvelous engineering works and an array of exotic plants fit those of the Hanging Gardens.

Therefore, we cannot say whether the gardens ever existed, let alone what happened to them, but they probably suffered a similar gradual neglect and decline. Babylon itself lost its status as a mighty ancient city to become an insignificant village so minor that its location was considered lost for centuries.

The Fate of the 7 Wonders of the Ancient World

While it is hard to accept the loss of these incredible monuments that took so much effort to create, time humbles all things. It is, nevertheless, interesting that it is the oldest wonder is the only one still standing. The idea of preserving the remnants of the past purely for the sake of preserving the past rather than for some continuing religious, practical, or political function is a surprisingly new idea. The notion that we would simply abandon the Empire State Building or the Eiffel Tower seems absurd to us, but countless people did that exact thing to their greatest works.

Whether it’s the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus or the ruined remnants of British castles, the vine-covered ruins of Chichen Itza, or the sunken remains of the Lighthouse of Alexandria, time and nature have often been left to reclaim human marks on the earth.