summary

- Stoicism, founded by Zeno of Citium, is an ancient Greek philosophy focused on virtue and a flourishing life (eudaimonia).

- A core tenet is that virtue is sufficient for happiness; external factors like health or wealth are considered indifferent.

- Stoics emphasize focusing on what is within our control – our actions and attitudes – rather than external outcomes.

- While also believing in free will, the Stoics believe the world is providentially ordered by a rational God, leading to acceptance of fate.

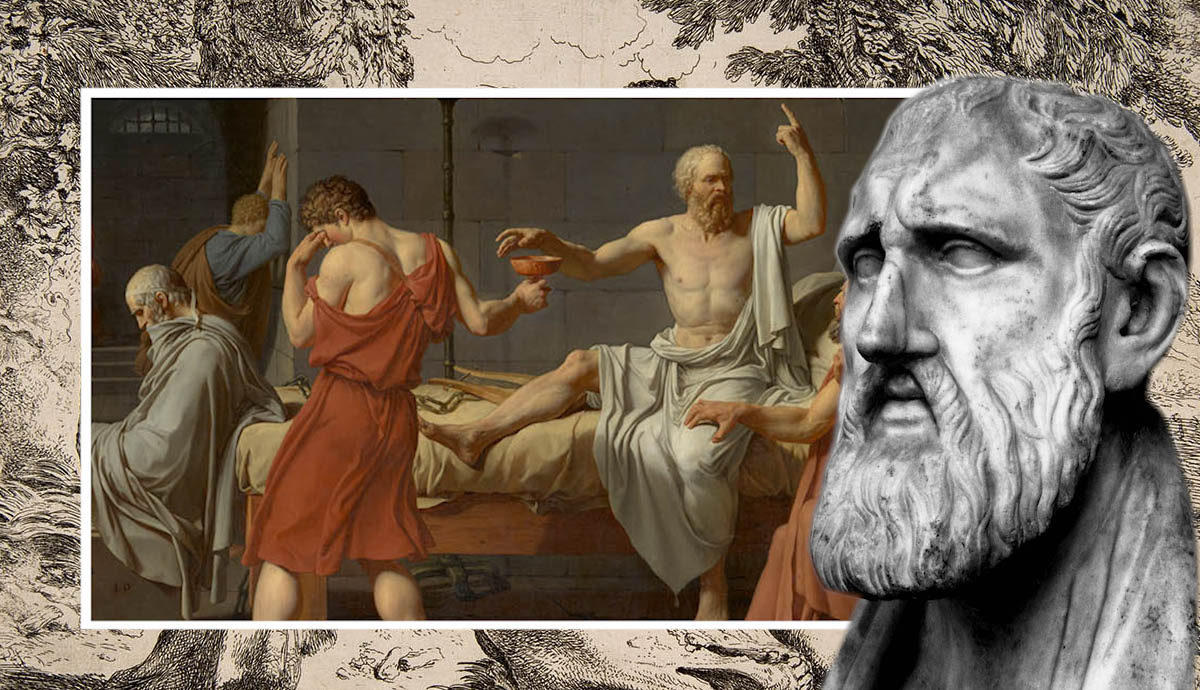

Stoicism is often portrayed as a harsh and pitiless philosophy for everyday life. Yet its devotees insist that Stoic philosophy is a liberating, joyous way of life. Founded by Zeno of Citium (Athens, 334–262 BCE), Stoicism remains a popular philosophy even today. The Stoics of ancient Greece considered themselves to be the heirs of Socratic moral philosophy and the natural philosophy of Heraclitus of Ephesus. Stoicism has had a lasting impact on the history of thought. It influenced the development of Christian morality and theology, as well as modern philosophy. Stoicism can be epitomized by three essential beliefs: (1) that virtue is sufficient for happiness, (2) that other so-called goods should be regarded with indifference, and (3) that the world is providentially ordered by God.

This article explains the origins of Stoic principles and the underlying beliefs of Stoic philosophy.

Moral Excellence: Stoic Virtue and Eudaimonia

The Stoics’ greatest legacy is their ethics. Like most other schools of ancient Philosophy, the Stoics think that the goal of ethics is eudaimonia. This Greek word has no direct English translation. It is often rendered as “happiness,” but eudaimonia doesn’t just describe a pleasant mood; it has a much more robust sense to it. Eudaimonia may be better translated as “human flourishing.” A life is eudaimonic when it has fully realized its potential for excellence and has lived up to the dignity appropriate to a human being.

The Stoics agreed with Aristotle’s moral philosophy to a certain degree. Aristotle defined eudaimonia as “activity of the soul in accordance with virtue,” (Nicomachean Ethics 1098a17). It is important to note here that, for Aristotle, eudaimonia and virtue were linked. The Greek word for virtue is arete. This word is not narrowly moral, but denotes any kind of excellence. For Aristotle, it is a quality that makes something good at doing what it does or being what it is. For instance, a good knife is a sharp knife. Therefore, one of the “virtues” of a knife is its sharpness.

For humans, virtue or arete is a state of character that makes humans good at being humans. Aristotle says that humans are rational and social animals (NE 1097b10, 1098a1-5). Thus, our virtues are qualities that allow us to succeed in acting rationally and cooperating socially. The list of virtues often varied from school to school and philosopher to philosopher, but most philosophical schools of thought in the ancient world agreed on four cardinal virtues. These were prudence, temperance, courage, and justice. These states of character are what allow us to act as rational and social beings.

Stoic Joy: Stoic Ethics & Aristotelian Ethics

Stoic ethics distinguishes itself from Aristotelian ethics with one significant difference. Stoicism teaches that virtue is sufficient for eudaimonia. In other words, virtue is all that is needed for it. Aristotle thought that virtue was necessary for eudaimonia, but not sufficient; more was still needed. For Aristotle, a eudaimonic life requires, in addition to virtue, some good fortune. To live well, one needs essential goods like shelter, good health, friendship, and wisdom. A virtuous person could be the victim of a tragedy that leaves them ill, homeless, or alone, and so, despite their good character, their life would not have gone well; they had failed to attain eudaimonia.

The Stoic school disagrees here. Looking back to Socrates and the Socratic school of Cynicism, ancient Stoicism claimed that all that is necessary to live a good life is being virtuous. All other so-called goods should be regarded with indifference. Even if the virtuous sage suffers multiple tragedies or even endures intense physical torture, he still has a chance at eudaimonia because these external things need not corrupt his virtuous character. Once you have become virtuous, nothing can ruin your life. In Stoic logic, virtue is the limit of happiness.

In several of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates says many things to this effect. For instance, in Plato’s Apology, Socrates says to his jury, “I do not think it is permitted that a better man be harmed by a worse; certainly he might kill me, or perhaps banish or disenfranchise me, which he [Meletus] and maybe others think to be a great harm, but I do not think so”.

Socrates’ words have been drawn upon by many Stoics. Rome’s Stoic Epictetus liked to paraphrase it as “Anytus and Meletus can kill me but not harm me.” In the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations, one of the most famous Stoicism books, he asks, “How can that which does not make a man worse, make the life of a man worse?” The obvious Stoic answer: it can’t. Only virtue is good, and vice is bad, and everything else is indifferent.

The Attitude of the Stoics: Indifference

It is the doctrine of indifference that is probably responsible for Stoicism’s reputation as harsh and pitiless. If only virtue is good, that means that health, pleasure, and even the welfare of our loved ones should be regarded with indifference. Yet Stoic indifference to external things is more complex than it seems. Although the ancient Cynics influenced the Stoic doctrine of virtue, and Zeno even studied under Crates the Cynic before founding his own school, the Stoic doctrine is distinct from the Cynic doctrine.

The Cynics thought that only virtue was good, and all other so-called goods ought to be scorned and actively avoided. The best life was a rigidly austere life of poverty and extreme asceticism. Stoicism, on the other hand, was a more practical philosophy. It says that we should not scorn externals, but regard them with indifference. The demands of virtue still require that we take care of ourselves and others, and the Stoics believe that such things can be choice-worthy without also being taken as ultimate ends.

The Archer Metaphor: Personal Responsibility

The “archer metaphor” was a favorite metaphor of many Stoics. A good archer does all that he can to hit his target. But once he lets go of the bowstring, it is no longer in his power to ensure that the arrow hits the target. A sudden gust of wind could blow the arrow off its course, or something could intercept the arrow before it hits the target. Nevertheless, the archer is a good archer because he did everything in his power to hit the target. If being a good archer is defined by one’s success at hitting the target, then whoever is good or bad is left up to chance. External factors that the archer has no control over can thwart his goal.

The Stoics think that one should not be blamed for things outside one’s control. Therefore, although a good archer aims at the target, the target is not his goal. It is not hitting the target that makes an archer a good archer, but merely doing all that he can to be a good archer. And this means he must try his best to hit the target while regarding hitting the target as indifferent to his ultimate goal. The Stoics suggest that we should have the same attitude towards our aims in life. Only our own actions and attitudes are within our power. And if you regard externals that are outside of your control as essential to happiness, you surrender responsibility for your own happiness to chance. The Stoics think this would be a grave mistake. They think it is preposterous for our ultimate good not to be up to us.

But why not just accept the grim possibility that the world is not set up with our welfare in mind? It seems plausible, as Aristotle thinks, that the good life requires some good luck. The Stoics refuse to accept this, because they believe that the world is providentially ordered by God to be as good as possible.

Stoic Physics: Nature as God

Stoic theology is pantheist. They believe that the cosmos is identical with God. Therefore, everything in the universe, such as stones, trees, animals, humans, and so on, are all parts of God. But one might ask, if God is just identical to Nature, how is this position any different from atheism? Why not instead just call Nature Nature, and leave God out of it?

In the modern era, Baruch Spinoza also identified God with Nature, and his contemporaries accused him of atheism. Stoics would insist that the cosmos can rightly be called God because, according to them, the cosmos is intelligent. To be more precise, the Stoics identify God as a universal mind or reason present in all things, and the physical cosmos is God’s body. Yet the Stoics claim to be materialists. Even the soul and the universal mind are present in all things made of matter, although of a rarified and nobler kind of matter.

The Stoics believe that the laws of nature are good evidence that the world was designed with purpose, and claim that humans’ ability to reason suggests that we are created by something that also possesses reason. Cicero, in his work On the Nature of the Gods, attributes the following argument to Zeno. “Nothing without a share in mind and reason can give birth to one who is animate and rational. But the world gives birth to those who are animate and rational. Therefore the world is animate and rational” (2.22).

Fate and Free Will

The Stoics follow the presocratic philosopher Heraclitus in claiming that the world is organized by reason, or logos in Greek. Heraclitus said, “all things come to pass in accordance with this Word [logos]” (Fragment 2). Logos has many meanings; it can mean “reason,” “argument,” even “speech” or “word.” Classicist G.M.A. Grube (1983) claims that the Stoic conception of logos likely influenced the author of the Gospel of John, which begins, “In the beginning there was the Word [logos], and the logos was with God, and the logos was God” (John 1:1).

Yet, unlike the God of the Abrahamic traditions, the Stoic God is not omnipotent. His power is limited by natural and logical possibility. These limitations, at least in part, explain why there is evil in the world. The Stoic Chrysippus, one of Zeno’s immediate successors, taught that the existence of good and evil were interdependent. It is logically impossible for good to exist without evil, so God designed a world that makes the best of this situation. Thus, evil may exist at the local level, but it is exploited by God to perfect the whole (Copleston 1993).

Once again, following Heraclitus, the Stoics believe that reality is in flux. Everything is constantly changing. Heraclitus most often likened this state of flux to fire, saying, “[the world] was ever, is now, and ever shall be an ever-living fire, with measures of it kindling, and measures going out” (Fragment 20). And to the Stoics, this all unfolds according to the rational plan of God. Thus, the Stoics are strict determinists. Time unfolds exactly according to God’s plan, and the history of the cosmos repeats eternally. Everything began in a conglomeration of fire, everything will collapse back into it, and then the cosmos will begin again, unfolding exactly as it always has. There is no reason for future world cycles to change because God’s plan for the cosmos is as good as it could possibly be. Despite believing in a deterministic universe, the Stoics did not deny human freedom.

According to O’Keefe, they are compatibilists, believing that fate and free will are compatible. The Stoics claim that your decisions and attitudes are up to you because they are your choices. It is with your intellect, self-discipline, and self-control that you decide to do what you do. You are not constrained from doing anything against your will, which is consistent with causal determinism. And because everything unfolds according to God’s plan, you should love your fate.

The Legacy of Stoicism: A Personal Philosophy

As can be seen, at its core, Stoicism is a personal and practical philosophy for daily life. It teaches controlling your thoughts and responses to the challenges presented by the world, and as such, taking personal responsibility for creating a joyous and fulfilling life. It also teaches an acceptance of fate and the value of living in the present moment without undue anxiety about the future. The Stoics argue that happiness is within our control. These are the most appealing elements of Stoic theory that have become influential in modern Stoicism.

Stoicism has had an immense impact on the history of thought. Their ethics and theology significantly influenced the development of Christianity and the thoughts of eminent philosophers like Kant and Spinoza.

Today, there has been a surge of popular interest in younger, future Stoic Philosophers. Much recent self-help literature looks to the Stoics for inspiration, and organizations like Modern Stoicism host international events like Stoicon and Live Like a Stoic Week to promote Stoicism as an attractive way of life. We can reasonably expect Stoicism’s legacy to survive long into the future.

10 Famous Ancient Stoicism Quotes for Modern Life

“The goal of life is living in agreement with nature.” – Zeno of Citium

“Well-being is realized by small steps, but is truly no small thing.” – Zeno of Citium

“It’s not what happens to you, but how you react to it that matters.” – Epictetus

“You become what you give your attention to.” – Epictetus

“We suffer more often in imagination than in reality.” – Seneca

“Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” – Seneca

“True happiness is… to enjoy the present, without anxious dependence upon the future.” – Seneca

“Waste no more time arguing about what a good man should be. Be one.” – Marcus Aurelius

“The happiness of your life depends upon the quality of your thoughts.” – Marcus Aurelius

“Accept the things to which fate binds you, and love the people with whom fate brings you together.” – Marcus Aurelius