According to legend, a generation before the Trojan War, a group of seven warlords, led by King Adrastus of Argos, stormed the Greek city of Thebes, attacking the famed Seven Gates of the city. Their assault failed, and all were killed except for Adrastus. Ten years later, their sons returned to Thebes seeking revenge. These are the myths recorded in the Theban Cycle, comprising three epic poems: the Oedipodeia, the Thebaid, and the Epigoni, as well as a related epic, the Alcmeonis. All of these epics are lost to us today, except for a few fragments, quotes, and references. Nevertheless, the Theban Cycle has left a lasting legacy, inspiring great tragedies like Oedipus Rex and The Seven Against Thebes.

What Is the Theban Cycle?

The Theban Cycle was a collection of epics that formed part of what later Hellenistic scholars referred to as the Epic Cycle. As the name suggests, the epics of the Theban Cycle took place in and around Thebes and were associated with several myths that are familiar to us today, largely due to the Classical Greek tragedies of Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides. The Theban Cycle covers three generations of heroes (four if you include Laius, the father of Oedipus), from Oedipus down to Alcmaon, who was of the same generation as the heroes that fought in the Trojan War.

Oedipodeia

The cycle begins with the Oedipodeia, an epic poem about Oedipus, his defeat of the Sphinx, and his ascent to power as king of Thebes. Ancient sources sometimes attributed the poem to Homer, and at other times to Cinaethon of Lacedaemon; however, the true authorship remains unknown. Comprised of 6,600 verses, the precise composition date is uncertain, but it was likely between the mid-8th and 7th centuries BCE.

Unfortunately, virtually nothing survives from this epic save for three fragments, which themselves don’t tell us the contents of the poem. Much of what scholars believe was in the epic comes from later plays about Oedipus written by Sophocles, though it is impossible to confirm what material the playwright took from the epic and what he invented. Events that may have been narrated in the epic are the rape of Chrysippus, the oracle to Laius about his future son, the exposure of Oedipus, the murder of Laius by Oedipus, the Sphinx’s riddle, and Oedipus’ marriage to his mother and its consequences.

Chrysippus was the bastard son of Pelops, and Laius was his tutor. Laius was supposed to be teaching the boy how to drive a chariot, but he instead brought him to Thebes and killed him, though some traditions say he raped him. Hera was then said to have sent the Sphinx to punish Thebes for letting Laius’ crime go unpunished. While there is no evidence that this story was included in the Oedipodeia, nor that it was derived from any epic, there is also no reason to believe that a version of this episode was necessarily excluded. It aligns with the overall theme of the Oedipus story and introduces the primary force that he must overcome.

The oracle’s warning to Laius against having a son comes after he and his wife, Jocasta or Epicaste, depending on the version of the story, were unable to have children. The seer Tiresias advised Laius to appease Hera in her role as goddess of marriage, but he chose instead to go to Delphi and ask Apollo. The god told him that he should not have a son because if he did, he would be killed by him. Laius got drunk one night and slept with his wife, begetting Oedipus despite the oracle’s warning. He pierced the baby’s ankles and left him to die of exposure on Mt. Cithaeron. Fortunately for Oedipus, he was discovered by a shepherd and brought to the Corinthian queen to be raised.

When Oedipus grew older, he was accused of not being the true son of the people who had raised him, so he went to Delphi to ask the oracle who his parents were. The oracle told him that if he returned home, he’d kill his father and marry his mother. Believing that the people who raised him were his real parents, he decided not to return to Corinth and instead headed towards Thebes. On the road, he encountered an old man and some servants at a crossroads. They tried to push him off the road, so Oedipus killed them and continued on his way. What he didn’t know was that the old man was Laius, fulfilling the first half of the prophecy.

Arriving in Thebes, Oedipus found it being threatened by the Sphinx. The scholion on Euripides’ Phoenician Women wrote that the Sphinx killed Haemon, Laius’ nephew, who was the last and most illustrious of the Sphinx’s victims. This was also possibly the reason for Laius’ fatal journey to Delphi, to ask the oracle how to deal with the Sphinx. Creon, the father of Haemon and brother of Jocasta, in the absence of Laius, declared that whoever was able to save the kingdom from the Sphinx would be given the throne.

In Sophocles’ tragedy, this was envisioned as the solution to the Sphinx’s riddle; however, vase paintings depict Oedipus slaying the monster with a sword. It is uncertain whether the riddle was a later invention or whether the painter of the vase was trying to convey the story in an exciting and active manner, given the static medium in which he was working. Regardless, Oedipus defeated the Sphinx and became king, marrying Jocasta.

In Sophocles’ plays, Oedipus’ children were by Jocasta, but Pausanias doubted this, citing his source as the Oedipodeia. According to him and other sources, Oedipus never had children by Jocasta. He stated that their relation was straightaway revealed to them by the gods and that Oedipus’ children were from his second wife, named Euryganeia. The epic may have ended with Oedipus’ death and funeral at Thebes, or with his fall from power after cursing his own sons, as is featured in the following epic.

Thebaid

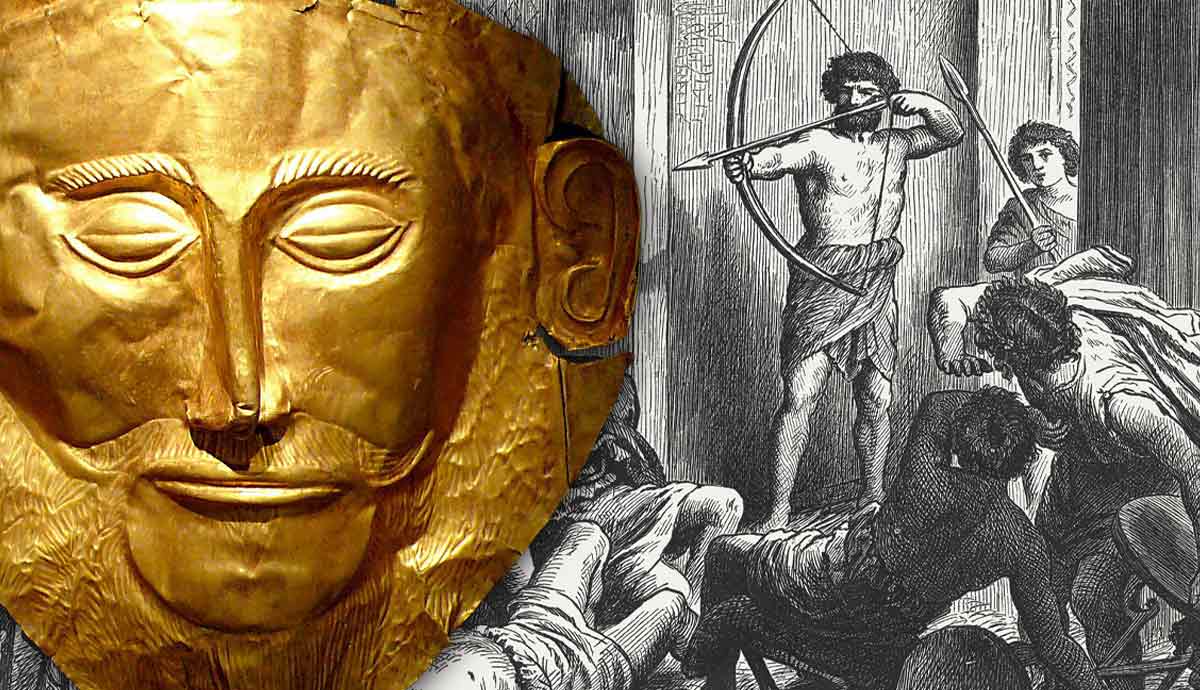

The Thebaid told the story of seven warlords under the command of King Adrastus of Argos and their unsuccessful siege of the city of Thebes. It has been attributed to Homer, suggesting the antiquity and prestige of the poem, but the actual authorship remains in question. There are more surviving fragments of this epic than of the Oedipodeia, but still an insufficient amount to reconstruct the contents of the poem. However, using classical tragedies and references from other ancient sources, we can guess the plot with some confidence.

It began with an invocation of the Muses, a common feature of epic that’s also seen in the Iliad and Odyssey. There are then two fragments that speak of the curse that Oedipus placed upon his two sons, Eteocles and Polyneices. Athenaeus wrote that the reason for the curse was that they placed golden cups in front of him that he had forbidden. The cups belonged to his late father, Laius, so he was not only upset at his sons for disobeying him, but also at being reminded of his murdered father. The curse was that they would never divide their inheritance peacefully. A separate account from the scholion on Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus states that the curse was due to the sons’ habit of sending the shoulder of sacrifices to Oedipus, but on one occasion, for unknown reasons, they sent him a haunch. Oedipus thought his sons were deliberately sending him the wrong portion and took it as an insult. He cursed them to die at each other’s hands.

The curse took effect immediately, and when Oedipus either died or exiled himself, as narrated in Sophocles’ plays, Polyneices and Eteocles began to argue over their inheritance. It was eventually decided that either Polyneices would receive their father’s wealth while Eteocles received his lands and title, or that they would alternate rule of the kingdom. Polyneices left Thebes and went to Argos, where he encountered Tydeus and King Adrastus. Due to a prophecy Adrastus had received from the Delphic oracle, he married his daughters to the two warriors and promised to restore them to their native lands. Adrastus planned an expedition to Thebes with the aid of seven warlords. There are various names that are attributed to these seven, but consistently named among them are Polyneices, Tydeus, and Amphiaraus.

Amphiaraus was a seer, and his wife, Eriphyle, a sister of Adrastus, pressured him into joining the expedition. On the way to Thebes, Amphiaraus saw signs that he interpreted to mean that the expedition was doomed to fail and that he was going to die. Adrastus and the warlords surrounded Thebes, with each warlord positioning themselves opposite one of Thebes’ famed Seven Gates, and Polyneices facing off against his brother Eteocles. Amphiaraus’ vision of doom came true, and all the Argive warlords, as well as Eteocles, died. The sole survivor was Adrastus, who managed to escape on his horse, Arion.

The end of the epic may have been Adrastus arranging the burial of the dead warlords, or it may have followed Sophocles’ Antigone. The play opens after Thebes’ victory against the Seven. Eteocles and Polyneices are dead, and the new king, Creon, has declared that only Eteocles may receive a proper burial, while Polyneices was declared an enemy of the city. Antigone, Polyneices and Eteocles’ sister, is conflicted over whether to obey the law of her uncle Creon, or to fulfil her duty to Polyneices and the gods by burying her brother. In the end, she buried her brother. As punishment, Creon condemns her to be buried alive in a tomb. The gods become displeased with Creon’s actions, and he eventually relents and allows Antigone to go free, but before she could be released, she committed suicide.

Epigoni

The next epic in the cycle was called the Epigoni, meaning the descendants, and took place ten years after the events of the Thebaid. Very little remains of the Epigoni, but what does remain implies that the poem was not independent but a portion of the Thebaid. Some scholars agree with this assessment, but much of the evidence is flawed, and the tradition of a second, avenging war against Thebes could only have begun after the story of the Seven had already been established. One of the extant fragments provides the first line of the poem, which features an invocation of the Muses, typical of epic poems.

Regarding the epic’s contents, other sources, such as Apollodorus, need to be consulted. The story of the Epigoni narrates the events of the sons of the Seven who mounted another assault against Thebes to avenge their fathers. They consulted the Delphic oracle, which told them that they would be victorious if they made Alcmaon, the son of Amphiaraus, the leader of the expedition. They ravaged villages until they encountered the Theban army led by King Laodamas. The king killed the son of Adrastus, the only survivor of the expedition of the Seven, before being killed himself. The rest of the Theban army then fled back behind the high walls of their city.

The seer Tiresias advised the Thebans to send a messenger to the Argives asking for a truce while they secretly escape from the city. The Argives, when they realized the city was empty, entered Thebes and plundered it, and then tore down its walls. The sons of the Seven sent all the best spoils to Delphi, including the daughter of Tiresias, Manto.

Some other possible episodes in the epic are the death of Tiresias at the spring of Tilphusa after the Thebans fled the city. Alcmaon’s murder of his mother may also have featured in the epic. He was commanded to do this by his father, Amphiaraus, before he left for war with the Seven because she had taken a bribe from Polyneices in exchange for making her husband go to war. But Alcmaon deferred vengeance until after the war. He later discovered that his mother had accepted another bribe from Polyneices’ son, Thersander, to persuade her sons to join the second war against Thebes.

Alcmeonis

The Alcmeonis is thought by some to be a section of the Epigoni, given the overlap in subject matter. Some scholars do not include this epic in the Theban Cycle. Its content relates to later Theban myths and features characters who later participate in the Trojan War, such as Diomedes. It has been said that the epic was wide in scope and varied in content, and likely narrated the life of Alcmaon after the Epigoni defeated Thebes. Given that the Epigoni is cited as being 7,000 lines, it leaves little room for a portion of the epic to be considered “wide in scope” if the Alcmeonis was in fact part of that epic.

The evidence in favor of it being its own epic is more convincing. One such point is that the Epigoni was often ascribed to either Homer or Antimachus of Teos, but the Alcmeonis is only ever cited as being written by “the author of the Alcmeonis.” The plot can be reasonably deduced from other sources, such as Apollodorus, and likely included the expedition against Thebes, Alcmaon’s murder of his mother, and his subsequent wanderings in Greece.

After the murder of his mother, Alcmaon became tormented by his mother’s Furies, avenging spirits that punished familial bloodshed. He left Argos and went to Arcadia to be purified of his blood-guilt. King Pergeus of Psophis conducted the purification and gave his daughter, Arsinoe, in marriage to Alcmaon. He gave her the necklace and robe of Harmonia, which were the bribes given to his mother by Polyneices and Thersander to force her husband and sons to join the wars. Yet the purification was ineffective. Apollodorus wrote that the land was becoming infertile, so Alcmaon consulted the oracle at Delphi, which commanded him to seek purification in a land that did not exist when he murdered his mother.

He wanders through Aetolia and Thresprotia until he finds the prophesied lands in the silts at the mouth of the river Achelous. There, he founds a settlement and is purified by the river god Achelous, who gives him his daughter, Callirrhoe, in marriage. A rivalry later breaks out among his two wives when Alcmaon returns to Psophis to recover the necklace and robe of Harmonia. He requests them under the pretense that he was going to donate them to Delphi when he actually intended to give them to Callirrhoe. Upon arrival, he was ambushed by Arsinoe’s brothers and killed.

Legacy in Greek Tragedy

As we’ve seen above, much of what we know of the Theban Cycle comes from the plays of Sophocles, Euripides, and Aeschylus. Greek tragic plays were always inspired by myth, though details could be invented to support the overall theme. Sophocles’ Oedipus the King and Oedipus at Colonus were likely inspired by the established tradition of Oedipus and the ill fate that befell him.

Aeschylus immortalized the story of the first Theban war in his play titled Seven Against Thebes. Euripides’ Phoenician Women also takes place during this war, but from the perspective of the Thebans trapped within the city surrounded by the Argive army. The Theban cycle even inspired a play by the Roman poet Statius titled the Thebaid. It is from these plays and others in the tragic tradition that we can reconstruct the scope of these lost epics.

Select Bibliography

Cingano, E. (2015). “Oedipodea.” M. Fantuzzi, Chr. Tsagalis (Ed.), The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Ancient Reception. A Companion, pp. 213–225.

Cingano, E. (2015). “Epigonoi.” M. Fantuzzi, Chr. Tsagalis (Ed.), The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Ancient Reception. A Companion, pp. 244–260.

Davies, Malcolm. (2015). “The Theban Epics.” Hellenic Studies Series 69. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

Debiasi, A. (2015). “Alcmeonis.” M. Fantuzzi, Chr. Tsagalis (Ed.), The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Ancient Reception. A Companion, pp. 261-280. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511998409.017

Lloyd-Jones, H. (2002). “Curses and Divine Anger in Early Greek Epic: The Pisander Scholion.” The Classical Quarterly, 52(1), 1–14.

Torres, Jose B. (2015). “Thebaid.” M. Fantuzzi, Chr. Tsagalis (Ed.), The Greek Epic Cycle and Its Ancient Reception. A Companion, pp. 226-243.