According to Freud, the uncanny is not just an unsettling or fearful sensation caused by the alien and unfamiliar. Spooky things, like living dolls, severed limbs, and doppelgängers, can be uncanny. This is because of their link to our subconscious, to repressed feelings of mingled pleasure and pain, which have a strange power to disturb us when they come back to the surface. Freud’s ideas had a seismic impact on the visual arts at a time when they were already beginning to explore abstraction, giving the surrealist movement a psychoanalytic impetus.

Sigmund Freud & Modern Art: Dreams and the Subconscious

Both Freud and surrealism are remembered today for their interest in dreams. Sigmund Freud had already published his Interpretation of Dreams (1899) by the time he wrote The Uncanny in 1919. This essay incorporates his theory that what we see in dreams reveals our repressed desires and fears, if—often—inscrutably. This is why dreams can frequently feel uncanny, presenting us with things “that ought to have remained…hidden and secret and has become visible,” as he defines the uncanny. These things gain the peculiar quality of feeling both familiar and estranged.

This mixture is a perfect analogy for surrealist art, which operates at the intersection of the familiar—often turning its eye to banal, everyday objects—and the strange, the inscrutable, and the dreamlike. Salvador Dalí‘s Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944) is the most overt example of a surrealist painting inspired by a dream, and is full of objects with potentially symbolic resonances.

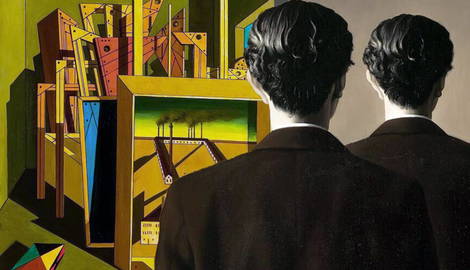

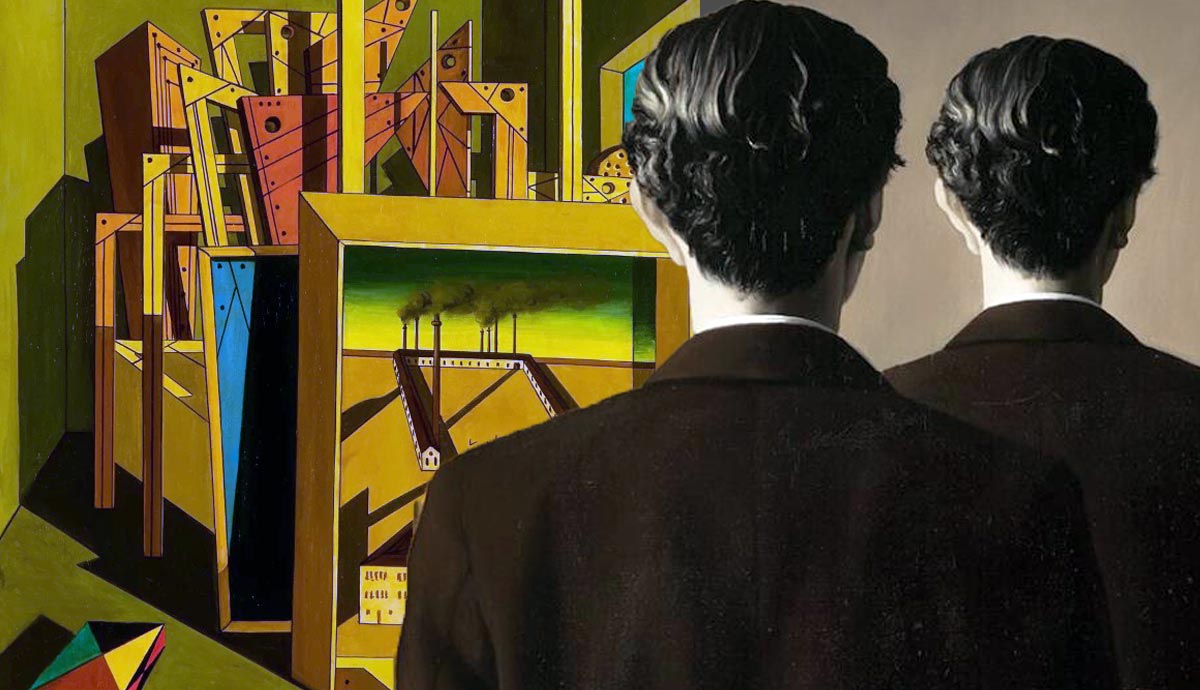

The metaphysical painting movement (which, like surrealism, was given its name by poet Guillaume Apollinaire) went even further in portraying the uncanny quality of dreams. What Freud calls our “sense of helplessness sometimes experienced in dreams,” coming as a result of confrontation with things we have repressed, is evident in the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico and Yves Tanguy.

De Chirico’s assemblages of seemingly unrelated objects, his long shadows, and his deserted cities represented in meticulous, geometric detail on smaller canvases within his paintings all evoke the simultaneous unreality and accuracy of dream landscapes. Tanguy‘s sparser landscapes are often dotted with abstract shapes that seem like strange shadows of real objects.

Leonora Carrington, although less in thrall to Freud than many of surrealism’s male proponents, nonetheless created uncanny works which blended ordinary objects and settings with a touch of the extraordinary, creating an effect similar to the literary genre of magical realism.

Dorothea Tanning, too, took ordinary spaces such as living rooms, hotel rooms, and corridors, and imbued them with an uncanny sense of disturbance.

The Doppelgänger or Double

Surrealist artists also took up Freud’s idea that the doppelgänger—the double, reflection, shadow, or twin—could be uncanny. To meet an eerily similar version of oneself might elicit “all those unfulfilled but possible futures to which we still like to cling in phantasy, all those strivings of the ego which adverse external circumstances have crushed,” at the same time as it might remind us of our mortality. The double destabilizes our sense of existence, making it hard to discern where ourselves begin and end.

René Magritte‘s paintings often feature doubles: from La pose enchantée (which Magritte subsequently cut into fragments and painted over) to Le double secret (in which the face itself becomes fragmented in its reproduction), both in 1927. La reproduction interdite (1937) and Les mystères de l’horizon (1955) also feature replicated figures, seen from slightly different angles.

Remedios Varo‘s dreamscapes, which, like Carrington’s, display elements of magic realism, often feature uncanny figures. These androgynous figures are repeated not only across Varo’s work but within the same canvas, as in 1956’s The Juggler, creating an unsettling disturbance of the ability to identify and distinguish one person from another.

Sigmund Freud’s theory of the uncanny did not only influence surrealist painting. Claude Cahun incorporated mirroring and doubling in several self-portrait photographs, including Que me veux tu? (1929). Cahun’s work embodies the Freudian attraction and repulsion in the idea of the double: the other self as both a future possibility and a threat to one’s stability, an idea that had a particular resonance for Cahun as a gender-nonconforming artist.

Dolls and Dismemberment

One section of The Uncanny focuses on a short story called The Sandman, published in 1817 by E.T.A. Hoffmann, whom Freud calls “the unrivalled master of conjuring up the uncanny.” Freud’s reading of the story focuses on the castration complex underlying the protagonist’s fear of having his eyes plucked out by the sandman, but the story contains another element that can also be classified as uncanny: a disturbingly lifelike wooden doll called Olympia.

Dolls, mannequins, puppets, and automata can unsettle our ability to distinguish the imaginary from the real, reigniting our infantile pretenses that the figurines we played with were real. These things become especially uncanny if we cannot immediately tell how they are being animated. For the same reason, but with the added psychoanalytical layer of the castration-complex on top, we get an uncanny feeling from seeing dismembered body parts which appear to retain some semblance of life.

The unparalleled master of exploring the uncanniness of dolls and dismemberment was the German surrealist Hans Bellmer. Apparently influenced by a performance of Jacques Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann, which adapted The Sandman for the stage, in 1933, Bellmer produced a life-sized doll of a young girl, whose body parts he continually disassembled and reassembled, and then photographed, in a range of settings and positions. The resulting collection, published as Die Puppe in 1934, caught the attention of major surrealists, like André Breton in Paris, because of the way it forced the viewer to readjust their objectifying gaze upon a thoroughly deconstructed female body.

Other surrealist photographers who used new technology to transplant body parts to strange new contexts included Claude Cahun and Dora Maar. Cahun’s Je tends les bras (1931/1932) shows a pair of arms appearing to extend from inside a wall. Maar, who appeared as a subject in many of Pablo Picasso‘s paintings, also created innovative work behind the camera, including Untitled (Hand-Shell) (1934). As the title suggests, it depicts a human hand appearing to grow out of a seashell.

More recent photographers have exploited the uncanny possibilities of their medium, which inherently disturbs our sense of the transience of each moment, preserving moments and figures which seem to belong to the past. In 1999, Hiroshi Sugimoto began a series called Portraits, which depicted waxworks of notable historical figures, transformed by the camera to appear alive.

Since the 1970s, Cindy Sherman has taken photographs that transform the human figure—often Sherman herself—into an uncanny semblance of a real person. From her Untitled series, number 345 is just one among many photos in which Sherman nods to Bellmer by breaking up and eerily reassembling a female doll’s body parts.

Modern Art & Disturbing Reality

The uncanny can be difficult to define, and much of Sigmund Freud’s original essay was preoccupied with describing what the uncanny is not. But for the surrealists and subsequent artists, it came to epitomize any vision in which reality is disturbed, whether by elements of unreality, dreams, magic, or by the sur-real: an exaggeration or hyperfocus on the real, familiar, and homely, which reveals the underlying anxieties and repressions beneath.

Magritte’s Man With a Newspaper (1928) is a prime example of the seemingly ordinary being used to trigger unease in the viewer. Its four panels show a banal interior scene, which initially seems to differ only in that the titular man and his newspaper appear in the first scene, but not the other three. A closer look, however, reveals minuscule differences in perspective between the other three scenes, and the viewer is left with an uncanny sense of confusion about the man’s disappearance and, indeed, Magritte’s rationale for presenting the four panels like a comic strip or game of “spot the difference.”

Seemingly innocent spaces take on a disturbed edge in photographs such as Maar’s Le simulateur (1936), which shows a boy in some kind of chamber, his body contorted in ecstasy or pain. Sherman’s photographs often invoke the uncanny through their air of nostalgia, reminding the viewer of photography’s strange ability to make the long-absent seem present. The photos in her so-called ‘disgust’ series transform ordinary objects like food, medicine, and makeup into symbols of decay and disintegration.

Finally, the uncanny made its way onto the screen in the works of David Lynch. His series Twin Peaks (1990-91, 2017) was set in a homely American town, where the presence of some kind of undetermined evil spirit is all the more unsettling because it moves among such ordinary surroundings. Lynch created enduringly uncanny and surrealist visuals, using motifs such as trees, owls, and logs, doppelgängers (with actress Sheryl Lee portraying both Laura Palmer and her cousin Maddy Ferguson), and dreamlike landscapes, such as the mysterious Red Room.

The instantly recognizable Red Room is both homely and unfamiliar. It is kitted out with sofas and lamps, and decorated with a Venus sculpture reminiscent of de Chirico’s paintings, yet it is a place where people speak backwards and become doubles of themselves. Like all the best examples of the uncanny, it is not outright sinister, but rather preys on our subconscious, attracting and disturbing us in equal measure.

Bibliography

Freud, Sigmund (1919). The Uncanny, translated by Alix Strachey.