For over two thousand years, successive societies forged the civilization of ancient Greece. From the early societies of the Bronze Age to its conquest by and cultural fusion with Rome, ancient Greece has had a significant impact on shaping the modern world. Understand the flow of ancient Greek history with this timeline from the Bronze Age to Roman Greece.

Timeline of Ancient Greece

- Bronze Age (c. 2000 BCE–c. 1100 BCE)

- c. 2000 BCE–c. 1450 BCE: Minoan Civilization flourishes on Crete.

- Large palace complexes (Knossos, Phaistos).

- Advanced art (frescoes, pottery) and undeciphered scripts (Linear A, hieroglyphic).

- Possible matriarchal influences.

- c. 1700 BCE–c. 1100 BCE: Mycenaean Civilization dominates mainland Greece.

- Monumental centers (Mycenae, Tiryns, Pylos).

- Linear B script (early Greek language).

- Trojan War legends emerge (later recorded in Homer’s Iliad).

- c. 1450 BCE: Minoan decline, possibly due to Mycenaean influence.

- c. 1200 BCE–c. 1100 BCE: Bronze Age Collapse – Mycenaean palaces fall; Greek Dark Age begins.

- c. 2000 BCE–c. 1450 BCE: Minoan Civilization flourishes on Crete.

- Dark Age / Early Iron Age (c. 1100 BCE–c. 800 BCE)

- Decline of writing, monumental architecture, and centralized power.

- Iron replaces bronze.

- Lefkandi (Euboea) shows continuity of trade and culture.

- Migrations (Dorian, Ionian) reshape the Greek population.

- Archaic Period (c. 800BCE–490 BCE)

- 776 BCE: First Olympic Games held.

- c. 800 BCE: Greek alphabet develops from Phoenician script.

- Homer composes Iliad and Odyssey (8th century BCE).

- Hesiod writes Theogony and Works and Days (7th century BCE).

- Rise of the polis (city-state): Athens, Sparta, Corinth, Thebes.

- Colonization spreads Greeks across the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

- 650 BCE–500 BCE: Age of tyrants and early political experiments.

- 508 BCE: Athenian democracy established under Cleisthenes.

- Classical Period (490 BCE–323 BCE)

- 490 BCE: First Persian War – Greeks defeat Persians at Marathon.

- 480–479 BCE: Second Persian War – Battles of Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea.

- 477 BCE: Delian League formed (led by Athens).

- 431–404 BCE: Peloponnesian War – Sparta defeats Athens.

- 404–371 BCE: Spartan dominance, then Theban rise (Battle of Leuctra, 371 BCE).

- 4th century BCE: Philip II of Macedon conquers Greece (Battle of Chaeronea, 338 BCE).

- 336–323 BCE: Alexander the Great conquers Persia, Egypt, and beyond.

- Cultural achievements:

- Parthenon built (447–432 BCE).

- Greek drama (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Aristophanes).

- Philosophy (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle).

- Hellenistic Period (323 BCE–31 BCE)

- 323 BCE: Alexander dies; empire splits into Ptolemaic Egypt, Seleucid Asia, and Antigonid Macedon.

- 3rd–2nd centuries BCE: Wars between successor kingdoms.

- Greek culture spreads to Egypt (Alexandria’s Library), Persia, and India.

- 146 BCE: Rome conquers Greece (destruction of Corinth).

- 31 BCE: Battle of Actium – Rome defeats Cleopatra; end of Hellenistic era.

- Roman Greece (146 BCE–330 CE)

- Greece becomes part of the Roman Empire.

- Greek culture influences Rome (philosophy, art, literature).

- Second Sophistic (Greek cultural revival under Roman rule).

The Bronze Age Civilizations (c. 2000-1100 BCE)

While impressive archaeological remains indicate a long history of habitation around the Aegean, particularly in the Cyclades islands, ancient Greek history can be said to begin with the Minoans and Mycenaeans. Part myth, part archaeological fact, these Bronze Age societies remain mysterious.

Minoan Civilization (c. 2000-1450 BCE)

The Minoans flourished on the large island of Crete between around 2000 BCE and 1450 BCE. Their complex “palaces,” bright frescoes, and intricate ceramics, which spread from Crete to influence the Aegean and beyond, earned the Minoans the label of one of Europe’s first civilizations. At the heart of this society were the large complexes discovered at Knossos, Phaistos, and around Crete, referred to as palaces. The palaces gave the Minoans their name, as the vast and intricate rooms, corridors, and courtyards of Knossos evoked the myths of King Minos and the Minotaur’s labyrinth when they were discovered by Arthur Evans in the early 20th century.

The function of the palaces is disputed. A dynastic seat, ritual center, or storage and distribution points are all possibilities. Like the palaces, much remains uncertain about this culture. The Minoans kept written records using two scripts, hieroglyphic and Linear A, both of which are still undeciphered, leaving the Minoan language open to question. The prominence of women in the frescoes has long sparked questions about a possible matriarchal focus in society.

Minoan influence spread beyond Crete, leaving a series of archaeological sites around the Aegean, and later giving rise to myths of a powerful seafaring society. Around the middle of the 15th century, the Minoan palaces went into decline. This has been linked to the emergence of the Mycenaeans on mainland Greece.

Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700-1100 BCE)

Like the Minoans, the Mycenaeans take their name from the discovery of large, monumental centers and their mythology. Covering the late Bronze Age from around 1700 BCE to 1100 BCE, the Mycenaeans are seen as the origin of the later tales of the Trojan War and the inspiration behind Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Just as in the poems, this was a world of rich warrior kings and massive fortifications, with Mycenae in the Peloponnese the most prominent. The Cyclopean walls of Mycenae and the nearby Treasury of Atreus tomb are still amongst the great sites of Greece, as is the gold displayed in Athens.

The Mycenaeans suffered as part of the widespread Bronze Age collapse that occurred in the 12th century BCE. While the physical remains were forgotten or built over, the Mycenaean world gave birth to a series of legends that form the basis of much Greek mythology.

The Dark Age (c. 1100-800 BCE)

The centuries following the decline of Mycenaean civilization are not well known due to the disappearance of writing; they are therefore characterized as the Greek Dark Ages. That label is disputed, and alternative names for the period, such as Protogeometric, Geometric, or Early Iron Age, are often used to describe the period between roughly 1100 BCE and 800 BCE.

Many of the Mycenaean palace centers fell out of use or declined, being replaced by smaller settlements without monumental architecture. Archaeology has challenged the idea of a genuine “Dark Age.” Sites such as Lefkandi on Euboea appear to have continued, despite the collapse of the palaces. They maintained contact with the wider Mediterranean, and there was eventually a return of monumental architecture. These long centuries witnessed numerous significant changes, as iron replaced bronze, settlement patterns and burial customs evolved, and later stories mention migrations both into Greece from the north and across the sea to the eastern Aegean and Cyprus.

Archaic Period (c. 800-490 BCE)

Just as transformative, but better known, is the subsequent Archaic Age, which spanned roughly from 800 BCE to the beginning of the Persian Wars in 490 BCE. The Archaic era saw the emergence of many features we associate with ancient Greece, such as the city-state (polis), columned temples, literature (including works by Homer, Hesiod, and Sappho), philosophy, politics, and, in 776 BCE, the Olympic Games.

Specific names and events have come down to us from contemporary and later accounts, though some of these remain semi-mythical. After the Mycenaean script of Linear B was lost with the collapse of the palaces, a new Greek script emerged in the Archaic period, based on an alphabet derived from Phoenician characters. This allowed the growth of a literary culture. Homer, one of those figures of uncertain date and origin, recorded the epic poems of the Trojan War. Hesiod tells us about the gods and life in 7th-century Boeotia, while Sappho’s poetry continues to be read today. Literacy also meant written law and the debates over who had the authority to write it.

The most important development was the polis. While Greece retained a great variety of communities, such as tribes and kingdoms, the independent city-states shaped much of Greek society. This meant there would never be one single ancient Greece. Instead, what developed was a network of interlinked but competitive cities. On the mainland, Athens, Sparta, Corinth, Thebes, and Argos became the most prominent cities.

A wave of colonization saw Greek cities spring up around the Mediterranean and Black Sea from Sicily to the Crimea and southern France. As the polis was its own community, hundreds of political experiments were underway, which generated monarchies, tyrannies, aristocracies, and, by the end of the Archaic period, democracy. This often made Greek politics unstable but encouraged ideas and philosophy to flourish.

Classical Greece (c. 490-323 BCE)

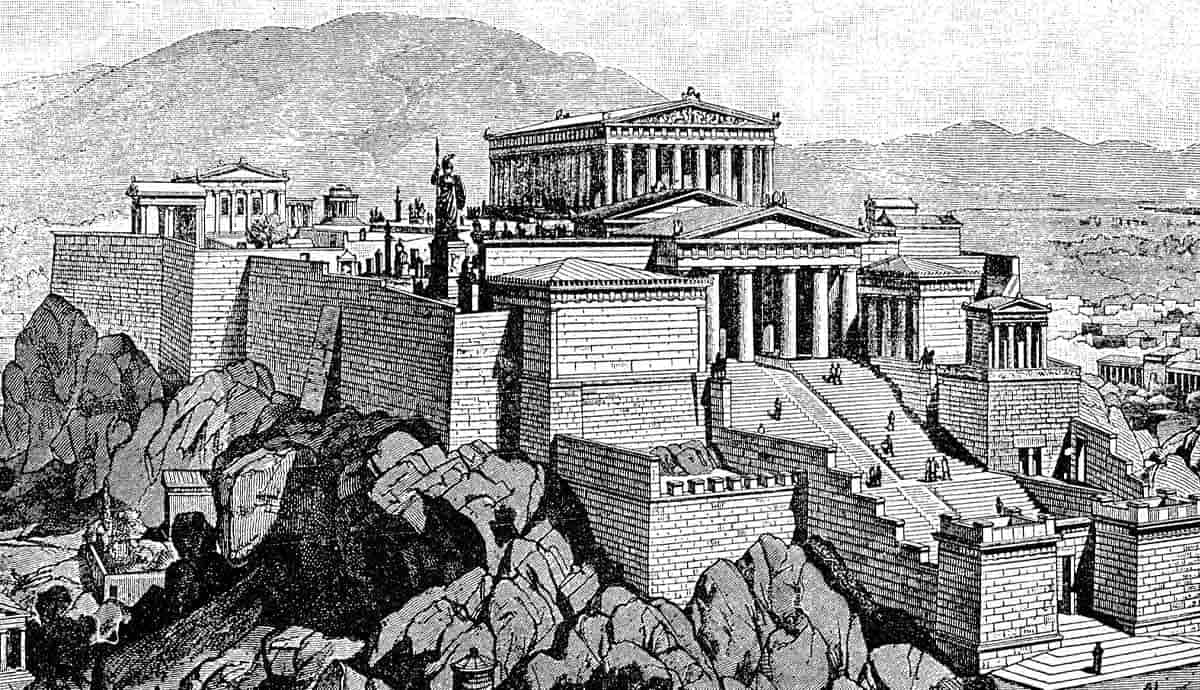

When most people talk about ancient Greece, it is the Classical period from 490 BCE to 323 BCE that they have in mind. The 5th and 4th centuries BCE were the time of Athenian democracy, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and the Golden Age of sites such as the Athenian Acropolis, Delphi, and Olympia.

The era began with a loose alliance of cities defeating two invasions by the Persian Empire in 490 BCE and 480-479 BCE. The war was a major turning point for the Greeks and was recorded by one of the first historians, Herodotus. The Athenians were at the heart of the Greek victories at Marathon and Salamis, while the Spartans created a legend with their stand at the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. The Persians continued to be a factor in Greek politics and controlled many cities on the eastern Aegean coast, but they never conquered the Greek mainland. Instead, the leading city-states fought for dominance, making the background to the glory of Classical Greece a series of devastating wars.

The 5th century was dominated by the rivalry between Athens and Sparta. Athens was a democracy, but it turned its anti-Persian Aegean alliance, the Delian League, into an empire. Sparta, a peculiar mix of monarchy and oligarchy, was the major land power controlling much of southern Greece through its Peloponnesian League. This rivalry led to the Peloponnesian War of 431 BCE to 404 BCE. Documented by the Athenian historian Thucydides, the 27-year war saw the defeat of Athens. However, Sparta did not long enjoy leadership of Greece. Another series of wars started almost immediately and culminated in the Theban victory over the Spartans at Leuctra in 371 BCE. By the middle of the 4th century, no polis could claim leadership for long, and they were ultimately overshadowed by the rise of the Macedonian monarchy in the north, under Philip II and Alexander the Great.

Despite the constant warfare, Classical Greece left a formidable cultural legacy. Once again, Athens was at the center of things. In the 440s, work began on the Parthenon and the complex of temples and monuments on the Athenian Acropolis, which remain some of the finest examples of Greek architecture. Beneath the Acropolis, the Theatre of Dionysus hosted the great era of Greek tragedy and comedy with performances written by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes. After Socrates roamed the center of Athens until his trial and execution in 399 BCE, Plato and Aristotle founded the philosophical schools of the Academy and Lyceum on the edges of the city. Across the Greek world, architecture, sculpture, and painting reached levels that would be admired and imitated for centuries.

The Hellenistic Period (c. 323-31 BCE)

The three centuries of the Hellenistic Age, from 323 BCE to 31 BCE, are less well known than the Classical Age but continued many of its developments. In this period, Greek culture expanded eastwards as far as Afghanistan, shaping the eastern Mediterranean for centuries.

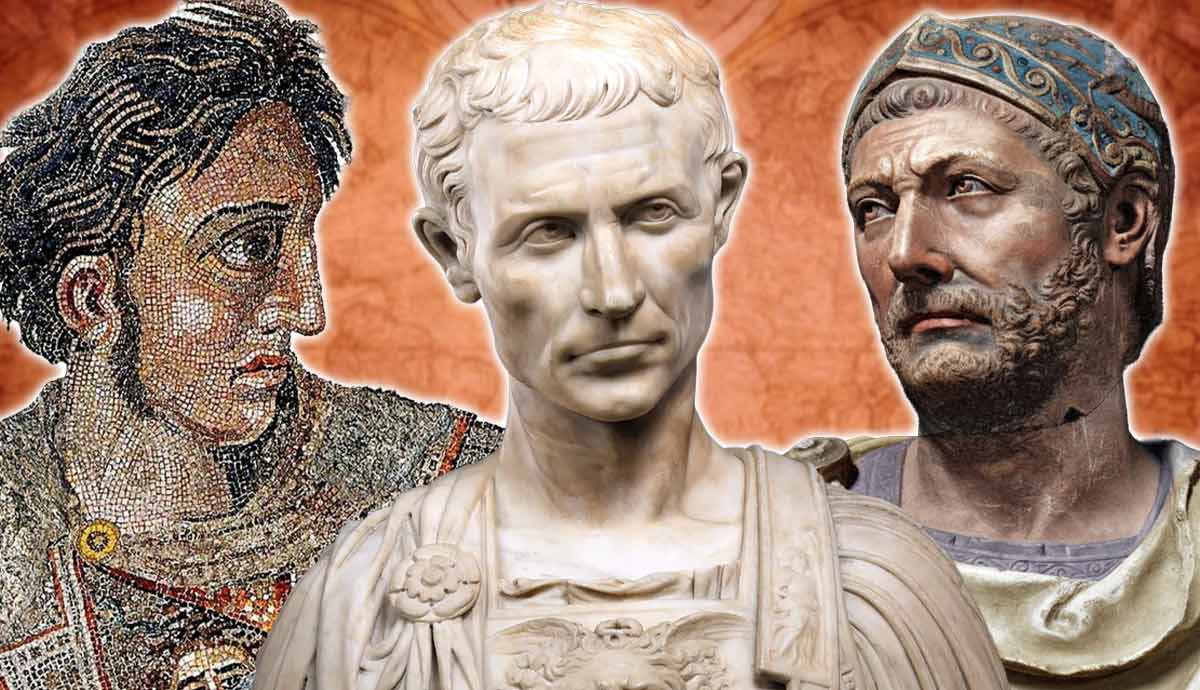

Philip II (359-336 BCE) transformed Macedonia from a peripheral northern kingdom to the foremost military power in Greece. His son, Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE), used this platform to launch one of the most extraordinary military campaigns in history. In less than a decade, he conquered the entire Persian Empire from the Aegean to Central Asia and the edge of India. Just before his 33rd birthday, he was dead, leaving behind a pack of successors (diadochi) who fought over his empire for almost half a century. The result was a division of Alexander’s empire into three great states: the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Antigonids in Macedonia, and the Seleucids in Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon.

The wars, alliances, and marriages between these three great kingdoms form the narrative of the Hellenistic Age, which, due to a lack of surviving historians, is less well known than its Classical predecessor. The Greek poleis struggled to hold on to what independence and cultural influence they could by forming federal states or burnishing their cultural capital. Royal cities such as Alexandria in Egypt and Pergamon in Asia Minor became centers of learning by hosting fabled libraries. Under the Ptolemies, Alexandria became a cultural capital of the Greek world and a storehouse of its previous achievements.

Just as in the Classical Age, no one state was able to assert total control, and the same pattern of wars played out again on a larger scale. Breakaway provinces, native rebellions, and dynastic strife all gradually undermined the Hellenistic kingdoms. As they faltered, the power of Rome in the west started to grow. A series of Macedonian Wars in the 2nd century BCE saw the Romans defeat and dismantle the Antigonid Macedonian Empire.

The last great Greek state, the Achaian League, was crushed in the Achaian War in 146 BCE. Pergamon handed itself to Rome a decade later. The Seleucid Empire crumbled under pressure from both the Romans in the west and the Parthians in the east. The Ptolemies held on to Egypt until the end of the Hellenistic Age in 31 BCE, when the first Roman Emperor, Augustus (then still known as Octavian), ended Cleopatra’s reign and brought Egypt under Roman rule.

Roman Greece (c. 146 BCE-330 CE)

The Greek world came under Roman rule in a piecemeal process. Having started in Macedonia in the 2nd century BCE, the Romans gradually expanded east until all the Greek states were either under Roman influence or had become Roman provinces. The impact of conquest was often devastating, as Greece frequently became the battlefield for Roman civil wars in the 1st century BCE. Despite the destruction, Greek culture would revive and, surprisingly, even flourish.

The Greek language, philosophy, art, and literature had long been popular among the Roman elite, who often spoke both Greek and Latin. Due to the Hellenistic spread of culture, the eastern Roman Empire remained Greek-speaking. Much of the surviving literature, sculpture, and monuments of Greece are from the Roman period. This is especially the case with sculpture, as statues were looted from Greece during their conquests and survive as Roman copies. Eventually, a Greek cultural revival emerged, known as the Second Sophistic. Greece remained the home of philosophy, and many Romans came to Athens to study. Plutarch wrote biographies of Greeks and Romans in the 2nd century CE, while much of our knowledge of Greece comes from Pausanias’ travel guide. Emperors such as Hadrian frequently toured Greece while Marcus Aurelius wrote his famous Meditations in Greek.

Although it only dealt with local affairs under Roman rule, the polis continued to exist. So too did the Olympic Games and the philosophical schools until Christianity put an end to them in late antiquity. When the western half of the Roman Empire fell in the late 5th century CE, the east continued on as a Greek-speaking Roman Empire (also known today as the Byzantine Empire) for another thousand years.