When considering the Trojan War, most people think of Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. But these two defining works only tell part of the story. The Iliad is set in the ninth year of a ten-year war, and the Odyssey is the tale of a hero returning after the conflict. Episodes such as “The Judgment of Paris,” “Trojan Horse,” and “The Sack of the City” are nowhere to be found in this pair of poems. So, where do these stories come from? Details about the war are scattered throughout a variety of works of Greek literature, poetry, and plays. It is the full compilation that tells one of the most epic tales of all time.

The Epic Cycle of the Trojan War

The story of the Trojan War is contained in a collection of works called the Epic Cycle. The word “epic” is derived from the Greek word epos, or “song,” which would strongly imply that they were intended to be sung to an audience. The word “cycle” is derived from the word kuklos, which means “circle,” as the works all revolve around a central theme.

There is some debate among scholars, ancient and modern, over which works actually belong in the Cycle. At its fullest extent, the Epic Cycle included the Titanomacy, which details the creation of the universe by primordial deities and Zeus’ defeat of the Titans; the tale of Oedipus; the Thebaid and Epigoni, two works about the Seven Against Thebes; and eight poems about the Trojan War. There are also some who believe that the poetry of Hesiod should be included, as well as the poem Alcmaeonis, only the name of which survives.

However, for the most part, the Epic Cycle usually only includes the works directly related to the Trojan War. These are the Cypria, the Iliad, the Aethiopis, the Little Iliad, the Sack of Troy, the Returns, the Odyssey, and the Telegony. Each work was composed separately by different authors as independent works, though they do seem to complement one another. For example, there are bridges that connect the works, such as the Iliad ending with the funeral of Hector and the subsequent work, the Aethiopis, beginning in the immediate aftermath of the funeral. This would imply that each work was separate but edited by later authors for a more coherent narrative. Many of the works also cover the same events, which would suggest that different editors put their own spin on each poem over the centuries.

The Authors of the Epic Cycle

The Epic Cycle, or the Trojan Cycle, which is the name given to the works directly pertaining to the Trojan War, is part of the rebirth of the literary tradition after the Greek Dark Age. After the Bronze Age Collapse in the 12th century BCE, the Mycenaean civilization fell apart, its inhabitants forgetting the hallmarks of their civilization, including monumental architecture and literacy. Oral tradition was preserved, and after writing was rediscovered in the 8th century BCE, the Trojan Cycle was among the first works of the newly revitalized literary tradition.

The oldest of the works of the Trojan Cycle are the Iliad and the Odyssey, which have been attributed to the poet Homer. Ironically, though these are the oldest works, they are also the only parts of the Cycle to still exist in their completed form. Homer is also believed to have composed the Epigoni and the Cypria, though this is subject to debate. As an alternative, the Cypria is believed to have been composed in the 8th century BCE by the poet Stasinus, or possibly Cyprias of Halicarnassus in the 6th century BCE. Around the same time, Arctinus of Miletus wrote the Aetheopis and the Sack of Troy. Lesches of Pyrrha wrote the Little Iliad in the 7th Century BCE, and the Returns was written in the late 7th or early 6th century BCE by Agias. Finishing off the series was the Telegony, which was composed by Eugammon of Cyrene in the 6th century. Many of these authors are purely speculative and are the best guesses of scholars.

Editors and Other Sources

With all but two of the works lost to history, with the exception of a few fragments, how has the well-known tale of the Trojan War come down to us? The foremost source was the works of Proclus. To make matters even more confusing, no one is certain who this Proclus was or even when he lived, either being a 2nd-century CE grammarian or a 5th-century Neo-Platanist philosopher. In either event, Proclus wrote a work called Chrestomathy. This is a summary of each of the works of the Trojan Cycle written in prose. This, in turn, was summarized in the 9th century by Byzantine scholar and patriarch of Constantinople Photius. This work is the most complete surviving summary of the Trojan Cycle that still exists.

In addition to these works, several ancient authors reference these texts or their contents. The historian Herodotus mentions the Cypria in his Histories, though he has his doubts as to Homer’s authorship. The philosopher Aristotle also mentions the works of the Little Iliad and the Cypria, where he takes on the role of the critic, complaining that the narrative of both of these poems was too disjointed and lacking any coherent structure. For example, he says that Cypria covers everything that happens leading up to the outbreak of the conflict until the Iliad takes over the narrative, with no overarching theme and seems to be random scenes thrown together.

Other works outside of the Trojan Cycle round out our current knowledge of the events of the Trojan War. These are in the form of plays, such as those by the Athenian playwrights Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles. For example, Aeschyus’ Orestia is a trilogy about the murder of Greek king Agamemnon. Later Roman poet Virgil would use the story of the Trojan War for the Aeneid, a mythological story about the founding of Rome, including a summary of the events in the Sack of Troy.

The Trojan War Narrative

The Trojan Cycle starts with the Cypria. Zeus plots with the titan Themis to start the Trojan War. At the marriage of Peleus, Eris starts a fight between Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite about who is the most beautiful. At Zeus’ suggestion, they agree to have the Trojan prince Paris act as judge. After some bribery, Paris chooses Aphrodite, who promises him the hand of Helen, the most beautiful woman in the world. Paris then steals Helen away from her husband, Menelaus, the king of Sparta, who goes to his brother, Agamemnon.

Paris and Helen, after a bit of a detour, arrive in Troy and are wed while the Greeks gather up their forces. After some misadventure, the Greeks land near Troy and, after some fighting, manage to establish a beachhead. Over the next nine years, Achilles leads the Greeks to capture several surrounding cities and cattle herds, taking Briseis as a prize. The work ends with Zeus planning to separate the matchless Achilles from the Greek cause to give the Trojans a fighting chance.

The next work is the Iliad. Easily the longest of the works in the cycle, it begins with Apollo sending a plague among the Greeks after Agamemnon refused to give back the daughter of the priest Chryses, who was captured. To stop the disease, the girl is returned, but the embittered Agamemnon steals Briseis from Achilles. This insult causes Achilles to refuse to fight. Pressing their advantage, the Trojans launch a counterattack. Fighting ensues, and the Greeks and Trojans, joined by the gods, do battle. During the fighting, Achilles’ friend Patrocles is killed by Trojan prince Hector. Achilles rejoins the fighting and kills Hector, desecrating the body. King Priam recovers his body, and a funeral is held.

The next book is the Aethiopis. The story picks up in the aftermath of Hector’s funeral with the arrival of Amazons, led by Penthesileia, who is killed shortly after by Achilles. Ethiopians then arrive, led by Memnon, who kills Antilochus, another friend of Achilles. Once again driven into a rage, Achilles attacks Troy, when Paris, aided by Apollo, shoots the warrior in his heel, killing him. After the body is recovered by Odysseus and Ajax, a funeral for Achilles and Antilochus is held, and Odysseus and Ajax feud over Achilles’ armor. There is some confusion over whether the dispute and Ajax’s subsequent suicide happened here or at the beginning of the next book.

The Fall of Troy Narrative

The story continues with the Little Iliad. After losing his bid for Achilles’ armor, Ajax becomes enraged, slaughtering a herd of sheep. Humiliated, he commits suicide and is buried in shame at the order of Agamemnon. A Greek prophet then states that Troy will only fall if they acquire the arrows of Herekles that were left with Philoctetes on Lemnos after being bitten by a snake. The arrows and Philoctetes are by Odysseus and Diomedes, Philoctetes is healed and then kills Paris in single combat, avenging Achilles.

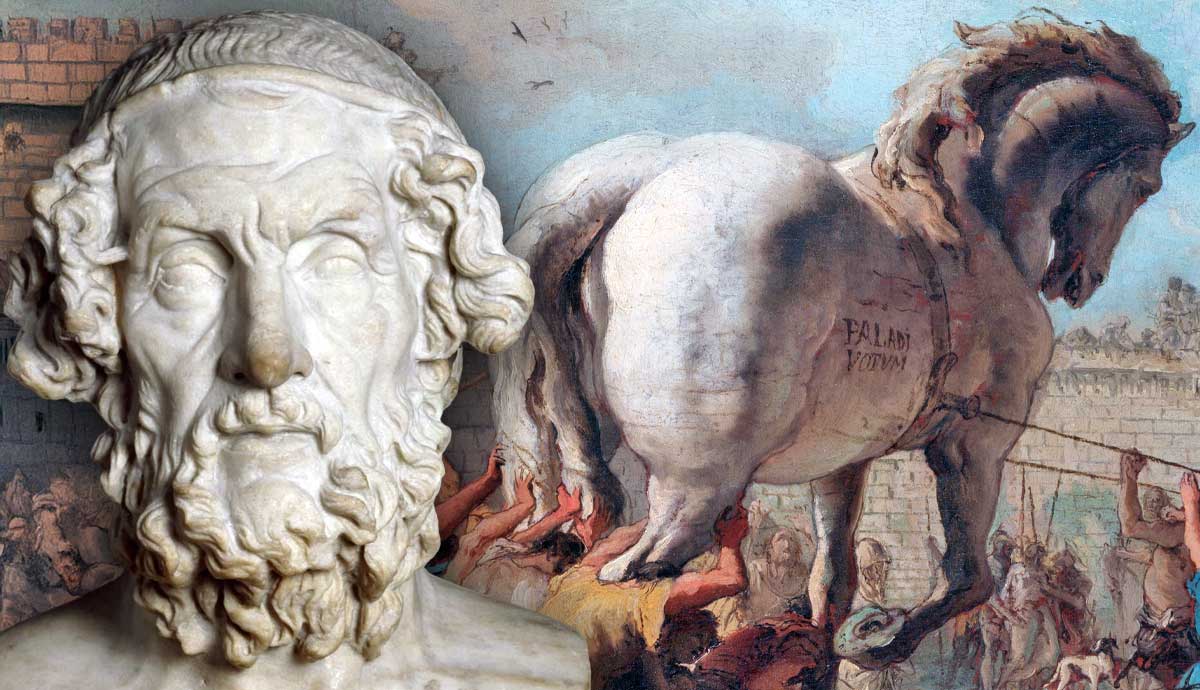

Another prophecy states that Troy will only fall if the Palladium, a statue of Athena, is taken from the city. Once again Odysseus and Diomedes take up the task and sneak into the city and steal the Palladium. They are spotted by Helen, but she stays silent. After other prophecies are fulfilled, the Greeks build a hollow wooden horse and abandon their camp. The Trojans then take the horse into the city, tearing down a section of wall, confident in their victory.

Though some of the destruction of the city is described in the Little Iliad, the majority of the city’s fall was recorded in the Sack of Troy. The Trojans discuss what to do with the giant wooden horse outside their city and then decide to bring it into Troy. During the night, the Greek warriors hidden in the Trojan Horse leap out and take the city. Some Trojans are killed, such as Priam and Astyanax, the son of Hector, while others, such as the prophetess Cassandra and Andromache, the wife of Hector, are taken captive. In the confusion, the altar of Athena is damaged. In response to this sacrilege, Athena plots her revenge on the Greeks as they prepare to return home.

Aftermath of the Trojan War

The Greeks return home after the war in the Nostoi, or Returns. Angered by the damage to her altar, Athena sows confusion among the other Greeks. While Nestor and Diomedes return home without incident, Menelaus and Helen are blown off course and end up in Egypt, staying there for a few years. Agamemnon and his entourage are hit by a storm, killing Lesser Ajax, and are blown off course. After he returns, Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus kill the king. Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles, takes an overland route and returns home after making sacrifices to the gods. By the end of the work, the only hero unaccounted for is Odysseus.

Odysseus’ return journey is described in the Odyssey, the other work that remains intact. One of the most famous pieces of literature, the Odyssey describes a decade-long journey as the Greek hero is blown around the Mediterranean, trying to get back to his home in Ithaca. He encounters the Lotus Eaters, the Cyclops Polyphemus, and the witch Circe. He journeys through the underworld, the twin hazards of Scylla and Charybdis, meets the nymph Calypso, and has other adventures.

He eventually returns home and, while in disguise, observes numerous suitors vying for the hand of his wife Penelope. A contest is arranged in which whichever suitor could string Odysseus’ bow and shoot an arrow through a line of axe heads would win Penelope’s hand. Odysseus is the only one there strong enough to string the bow and complete the challenge. Odysseus, along with his son Telemachus and a loyal servant, then slay the interlopers. After two decades apart, he and Penelope are finally reunited.

The final book is a followup to the Odyssey, called the Telegony. After burying the slain suitors, Odysseus travels to the mainland to make sacrifices. It is there that he weds Callidice, a local queen, who bears him a son, Polypoetes. He then helps fight against a rival kingdom and is almost defeated when Ares intervenes on the enemy’s behalf. Athena then arrives, and the gods and mortals battle, which ends in a stalemate after Apollo breaks up the fight.

After the death of Callidice, Odysseus makes Polypoetes king and then returns to Ithaca. At the same time, Circe, who had imprisoned Odysseus for years, gave birth to their son, Telegonus. Seeking his father, the youth travels by sea but is shipwrecked in Ithaca. After attempting to steal cattle, Telegonus is confronted by Odysseus, unaware that they are father and son. After a fight, Odysseus is mortally wounded, and the two recognize one another, much to everyone’s horror. After his death, Telegonus takes Odysseus’ body, Penelope, and Telemachus back to Circe’s island, where the hero is buried. The work ends with Telemachus marrying Circe and Telegonus marrying Penelope.

This is the final work in the Trojan Cycle. Other than the Iliad and the Odyssey, there are about 150 total lines that have survived to this day. The entire narrative of the Trojan War, which is so deeply ingrained in popular memory, is due to other authors who either summarized the tale or used it in their own works, a fragile link to this incredible piece of literature.